Part I: Birth of the Kiss

The story begins with a terrible vacation.

Or perhaps “terrible” is too obvious—Vampire’s Kiss is not the sort of movie that could have emerged from a jolly seaside honeymoon. It is grim, deranged—a comedy so dark its protagonist, played with wild fervor by Nicolas Cage, literally believes he is allergic to daylight. But these were particularly bad vibes. It was January 1986, and a promising young screenwriter named Joseph Minion was miserably depressed. “It was a very bad time,” Minion says. “It was very cold. I was in a toxic relationship.”

Minion’s first film, the night-from-hell classic After Hours, had miraculously caught the eye of Martin Scorsese, who directed it in 1985, bringing Minion’s vision of urban alienation to a mass audience. His second script, a road movie called Motorama, was trapped in development hell—thus one cause of his misery. He and his girlfriend, film producer Barbara Zitwer, decided to leave town. They caught a cheap courier flight to Barbados. Even there, Minion couldn’t shake his tortured mental state. Zitwer intervened. “She said, ‘Listen. I’m going back to New York. You’re in a bad mood. You sit here, write a script,’” Minion recalls. Zitwer, who’d met Minion in film school and then risen up the ranks as a location scout and associate producer for filmmaker Larry Cohen, thought a new script might lift his spirits. “She said, ‘Whatever you write, I promise I’ll get it made,’” Minion recalls.

Zitwer remembers the conversation differently: “I told him to write a script that would be set in Barbados. We’ll shoot it there. I love the Caribbean.”

A nice idea, but not one Minion heeded. When he met a stranger at the hotel who loved horror movies, inspiration struck: Why not write a low-budget horror film? Minion spent two weeks cooped up in a hotel room overlooking palm trees, writing. “I was just alone with my demons,” he says. “I rented a typewriter. I pounded it out.” One night, he was staring out the open window and saw a group of bats fly out of an opening in the roof. A sign? “It was like, Oh my God. This is the universe speaking to me.”

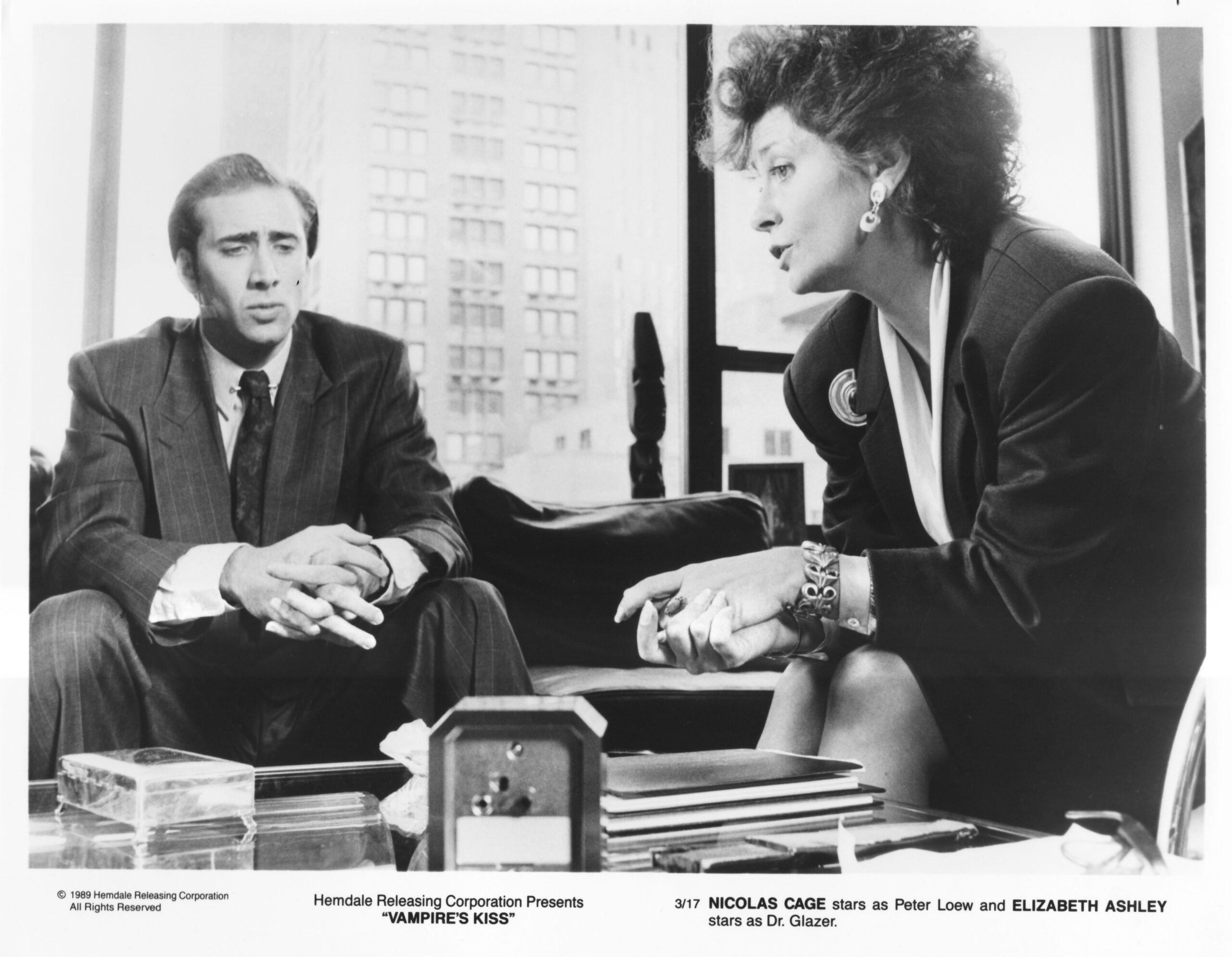

The result was Vampire’s Kiss, a darkly comic story about a mentally disturbed literary agent named Peter Loew, whose empty, unfulfilled romantic exploits cause him to rant to his therapist and torment his poor secretary, Alva. When Peter gets bitten by a vampiric lover named Rachel, he believes he’s turning into a vampire and descends into insanity, ranting and raving and begging for death. The film regards Peter’s spiraling madness with unflinching fascination, as he kills a woman in a nightclub and hallucinates in the streets.

The story shared some similarities with After Hours: the buzzing urban anxiety, the sexual alienation, the grim view of Manhattan nightlife. But even more twisted. Minion admits the energy behind the script had to do with “cauterizing this really toxic relationship.” He planned to direct the movie himself.

Minion tells me all this three decades later, at a diner on West 57th Street. He is 61, with dark glasses and a tattoo of the word “Fellini” on his right forearm. The diner is overpriced. “This is starting to become a rich man’s town,” he mutters, scanning the menu. It’s hardly the Manhattan he wrote about in After Hours and Vampire’s Kiss, a gritty town populated by Mohawked punks, art studios, and rampant crime. That city was both thrilling and nightmarish. “Darkness is like my middle name,” Minion says. “I have a very dark view. I don’t feel very optimistic about anything.”

Minion admits he was nervous about meeting me. When people talk about Vampire’s Kiss, they often treat it as a joke. Several years ago, for instance, he was invited on a podcast to talk about the film. He said yes, but never heard back. Then he realized the podcasters had recorded the episode without him. “For at least an hour, they kept using the word ‘bad.’ ‘This is so baaad!’ ‘This is awful, oh my God!’ These two guys were basically dissing the movie.”

He couldn’t understand it. The film is a comedy, but it was never a joke. It’s personal—and dark. Cage understood that. “I always saw the movie as a story of a man whose loneliness and inability to find love literally drives him insane,” the actor said while recording the DVD commentary track. (Cage declined to be interviewed for this story.) Minion is vaguely aware that Vampire’s Kiss has found a new life on the internet—that it has become the forefather of endless debates about whether Cage is a good actor; that it’s deeply beloved among the sort of weirdos who can recite the alphabet in the exact same cadence as Cage’s character; that scenes of Cage bugging his eyes out and terrorizing Alva have inspired endless memes and YouTube clips.

He shrugs that off. “It’s not Vampire’s Kiss. Vampire’s Kiss is a movie that starts frame 1 and ends frame 12,722 or whatever. I’m not responsible for this meme stuff. I love films.”

Part II: Cage Under Pressure

When Minion completed the screenplay in Barbados, he mailed it to Zitwer.

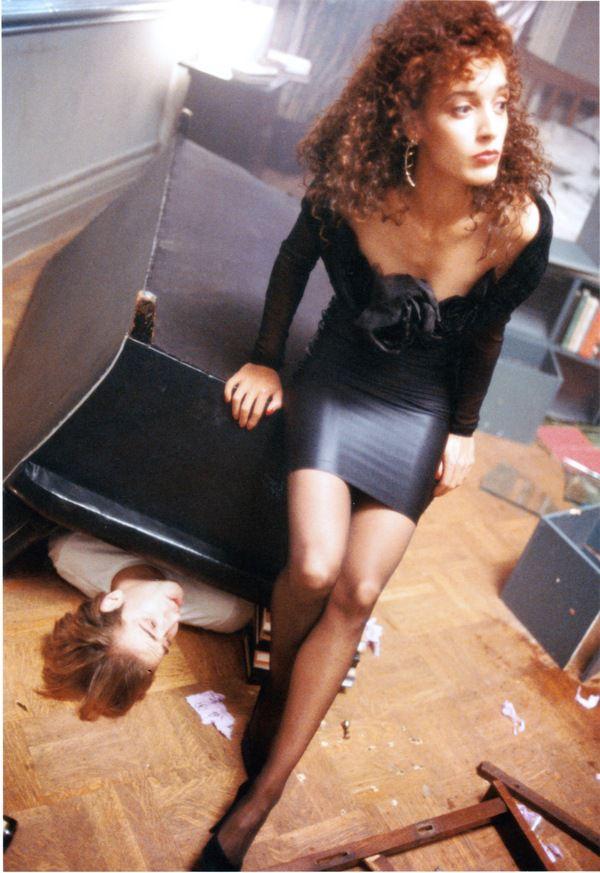

“I was completely horrified,” Zitwer says. “Horrified because I was Joe Minion’s girlfriend and living with him. And I read it and it was like … this is our relationship. To read someone write about this woman he’s in love with who’s like a vampire and destroying him—” Zitwer saw traces of herself in both Rachel, the woman who torments Peter, and Alva, the woman who’s tormented by him. (Later, producers toyed with the idea of casting the same actress in both roles, establishing a subliminal link between the vampire and the secretary. Jennifer Beals, then known for Flashdance, wound up playing the former part and Maria Conchita Alonso the latter.)

Despite her initial shock, Zitwer and her coproducer, Barry Shils, loved the script and immediately decided to get it made. The two had become close friends while working on Larry Cohen’s movies. Their circle also included Marcia Shulman, a friend of Zitwer’s who quickly became Vampire’s Kiss’s associate producer and casting director. They were young, hungry, and dying to make a movie of their own. “I basically gave up my entire career for two years to get Vampire’s Kiss made,” Shulman says. Armed with youthful naivete and one degree of separation from Scorsese, they found a willing financier in John Daly, the late British film producer, who was gathering a library of films for his own production company, Hemdale Film Corporation.

Casting brought its own drama. Today it’s utterly impossible to imagine Vampire’s Kiss without Cage’s unhinged brand of “Cage”-iness. Not so in 1986, when he was a young actor still finding his voice. Early on, Dennis Quaid was cast as the lead. “We got financing because of Dennis,” Shulman says. The choice makes sense if you think of Vampire’s Kiss as After Hours 2.0, Shulman theorizes. “In some ways, Dennis would have been the Griffin Dunne way to go—the sort of overwhelmed guy.” Instead, Quaid dropped out to star in Innerspace. “And then the scramble began.”

As the script circulated around Hollywood, the producers got word that Cage was interested. Shulman says, “I remember sitting with Barbara and Barry and saying, ‘We have no idea what it will be. … But he’ll get the movie made. And he’s always interesting.’” She remembered seeing Valley Girl and thinking, “Who is that guy?” In 1986, Cage was 22 and mostly known for appearing in the films of his uncle, Francis Ford Coppola. In Peggy Sue Got Married, his eccentricities became unmistakable. Cage took a highly surrealistic approach, including an oddly nasal voice, much to the annoyance of star Kathleen Turner, who wanted Coppola to fire him.

Minion met with Cage at a speakeasy in the West Village and was struck by his enthusiasm for the script: There was “this look in his eyes, like he was gonna really do something.” Cage was offered the role. He accepted. Then Minion decided not to direct the film after all—and everything fell apart. “I just had to move on,” Minion explains. “The darkness of it—I couldn’t inhabit it anymore.” He and Zitwer had broken up. It had been a stormy relationship and a dramatic breakup; the two could barely be in the same room, much less on a film set together for months.

Zitwer and her coproducers immediately began searching for a new director. They settled on a British newcomer named Robert Bierman, who had mostly directed commercials but charmed them with his excitement about Vampire’s Kiss. But there was one problem. Cage felt misled when he learned Minion wasn’t directing and dropped out. “I was getting a lot of outside pressure from my agent and people representing me that this was not a good move after Moonstruck, to make a movie of this nature with the vampire fangs and going off like that,” Cage says in the commentary. “I responded to the pressure and I broke.”

The scramble for a star began anew. Bierman had dinner with Judd Nelson. “He was very keen, his agent quoted $1 million, we dropped him immediately,” Bierman recalls. Shils swears he once personally handed the script to Steve Martin—“who seemed very interested,” Shils adds, “but his agency did not.” The producers tried to give the part to an unknown named Adam Coleman Howard, who’d auditioned well. “But [Hemdale] wouldn’t finance the movie with him,” Shulman says.

Perhaps Cage sensed it was his destiny to star in Vampire’s Kiss. The producers heard a rumor that he regretted dropping out. “He was kind of obsessed with the role,” Zitwer says. At lunch with their mentor Larry Cohen, they discussed the dilemma. Zitwer scoffed at the notion of working with Cage after he’d already dropped out. “And Larry looked at her and went, ‘Are you crazy? He’s gonna be a huge star!’” Shils recalls. Shils left the lunch, found a phone booth, and immediately called Cage. It wasn’t hard to convince him.

But it took another year to get his signature on a contract. Cage’s agent, Ed Limato, didn’t want him doing Vampire’s Kiss. “They wanted his next film to be a big Hollywood movie,” Shulman says—not a low-budget art film produced by a team of nobodies. Shils claims he had to sneak onto the set of Moonstruck and confront Cage just to get his agent to return his calls. Cage was ultimately paid $40,000, a reduced fee, and spent the money on his first sports car. In a 1989 Spin profile, he regretted nothing. “I did the movie for no money,” he said, “because I liked the script and I wanted to try something new with my acting.”

This was a profound understatement.

Part III: Fake Bats and Real Roaches

The most famous story from the set of Vampire’s Kiss involves a cockroach. A real one. The script had called for Cage’s character—in the throes of madness—to suck a raw egg. Bierman and Cage thought this was too tame.

Cage “said to me, ‘The thing I hate most in the world are cockroaches. They are my Room 101. … So let me eat a cockroach,’” Bierman recalls. “He wanted to eat the most frightening thing for him. I thought, ‘This is terrific!’ I sent my prop people down into the boiler room. … They brought me a box, divided up into little sections with tissue paper. The cockroaches were there lined up for me to cast. I think they’re actually called water bugs—they’re bigger than cockroaches.”

What you see on film is all nauseatingly real: Cage snatching a live roach, lifting it tentatively, chewing it like a madman. “I really [wanted] to do something that would shock the audience, something you would never forget,” Cage explained. It’s the only change he made to Minion’s script, which never underwent a single rewrite.

Zitwer was furious. She and Cage did not get along. She was frequently in the position of having to say no to his craziest ideas. “I was always infuriated with him but also thought he was completely brilliant,” she says. “Bob calls me and says, ‘Nicolas wants to eat a water bug instead of sucking on the egg.’ I’m like, ‘Fuck him! I’ve had it with him.’ I said, ‘Bob. It’s probably full of germs. He could get sick.’ Bob says, ‘Barbara, I think if Nicolas wants to eat a water bug on film, we should let him.’ I said first let’s call the doctor. I called the doctor. I said, ‘Would he get sick if he eats a water bug?’ And the doctor was like, ‘OK, that’s a weird question.’ But he says, ‘No. But have him drink some whiskey right after.’”

In Bierman’s recollection, Cage swigged 100-proof vodka to wash his mouth out afterward. They shot two takes. “The suspense of shooting it was astounding,” says cinematographer Stefan Czapsky. “He actually ingested the cockroach” both times. (When Shils later got a call from an animal rights group, he lied and said the cockroach walked away alive.)

That’s the energy Cage brought to the film set: frighteningly devoted to his performance and willing to go to extreme lengths to fulfill his creative vision. Sources say he often remained in character off-camera and was obsessive about the role. “He was a little kooky,” says Kasi Lemmons, who played Peter Loew’s initial love interest. “He was very, very into his character.” “He didn’t have a trailer or anything,” Czapsky adds. “In between scenes, Nic was always by himself. He wasn’t hiding. He was just in isolation and preparation for shooting. I remember hearing through a door that he was listening to some kind of weird chanting music. We’d laugh, like, ‘Nic’s in there, you know.’”

[Bierman] says, ‘Barbara, I think if Nicolas wants to eat a water bug on film, we should let him.’Producer Barbara Zitwer

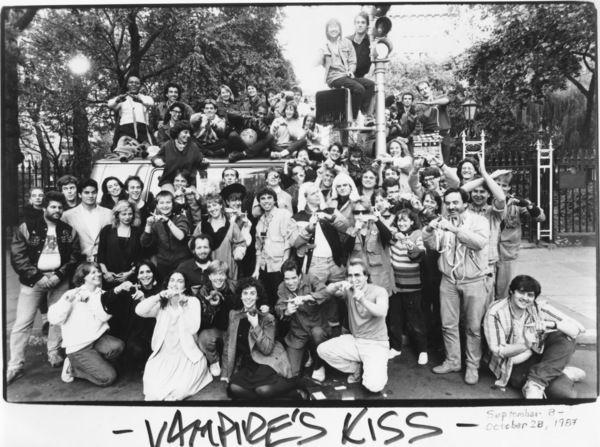

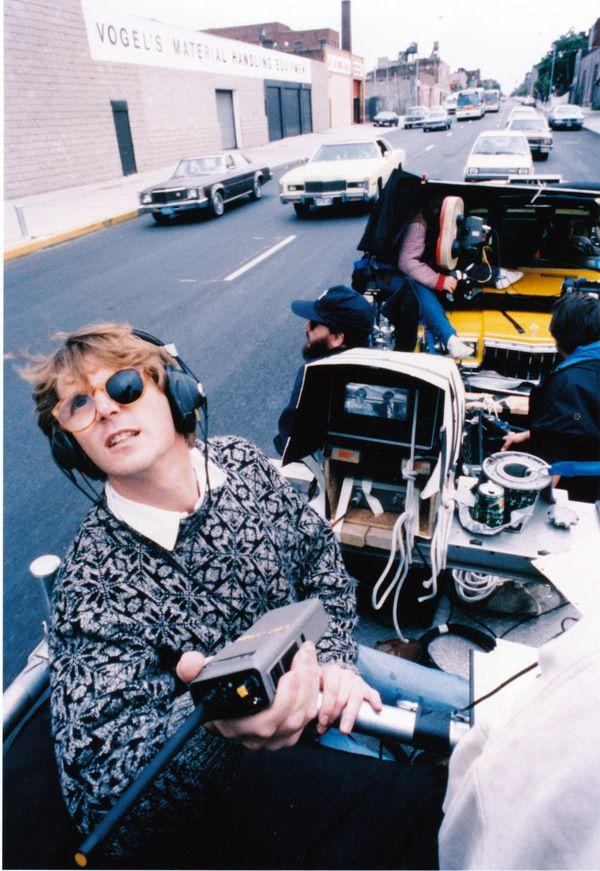

Vampire’s Kiss was shot on the streets of New York in seven harried weeks during the fall of 1987. Bierman has described the shoot as “complete chaos, from beginning to end”—but a beautiful and creative chaos. “Around us was chaos,” Bierman tells me. “At that time, Manhattan was full of bums and crazy people and the homeless. When Nic was on the street, we were shooting back on longer lenses. Some people didn’t know who he was. They just thought he was one of the crazy people on the street.” In one harrowing scene, a blood-splattered Cage prowls the streets with a wooden stake, incoherently begging strangers to kill him. Those strangers had no idea they were being filmed, Bierman claims. “Two of them were homeless people, who I think were quite frightened of him and ran away. It was an interesting way of galvanizing his character. He became part of the New York scenery at that time.”

“He just put himself into this environment of really pitiful people, dragging the stake down the street,” adds Czapsky. “I just set the camera up across the street and photographed it.”

The film depicts the city as a nocturnal den of sin and desperation. At one point, a dead body was being removed from a bar in a body bag as the crew prepared to shoot a scene in that bar. Bierman shrewdly used visual metaphors to represent what he viewed as Peter’s descent into hell. For instance, “in the office where he rapes Alva, he descends from his office into the basement. Metaphorically, he’s going down into his underworld. Mentally, he becomes more deranged down there. When he goes into the club, again, he descends into this kind of underworld. And then when he’s being helped—from his psychiatrist—he’s up high.”

The film’s budget was low—around $2 million—and producers saved money every way possible. They shot the office scenes for free in an empty city government building, which also became a makeshift production base. They recorded the eerie score in Budapest, because the orchestra was cheaper there, then ran out of cash and had to borrow money from teamsters to pay for a Dolby sound mix. For months on end, Zitwer’s parents were essentially financing the running of the production office. “Nic cost me $10,000 by humming Stravinsky’s Petrushka,” Bierman recalls. “The Stravinsky estate was still in copyright. So that’s why we didn’t have any money at the end.”

Another source of friction was Cage’s dislike of Beals, who’d been cast as the vampire woman a day before shooting. “He hated the idea of Jennifer,” says Shulman. “He just didn’t think she provided proper motivation—creatively, sexually, in any way.” Cage had wanted that role to go to his girlfriend, 19-year-old Patricia Arquette, but Bierman refused. Another young actress got the part, but dropped out right before filming because her fiancé threatened to break up with her if she made love to Cage on screen. When Beals took the role, Cage treated her so coldly that Shulman had to call Beals’s agent and make excuses (“Nicolas is in character”).

Cage eventually warmed up to Beals, but his methods remained bizarre. “To get turned on, Nic asked to have hot yogurt poured over his toes while he was doing a love scene with Jennifer,” Shulman recalls. Nobody could comprehend why yogurt got Cage aroused, but the crew obliged. “If you look at the shot, you don’t see his feet,” Shulman says.

One significant expense was the bat, which swoops into Peter’s room at the beginning of the film. Producers had hired a special effects designer to transport a mechanical bat from England. Cage hated it. He believed the scene wouldn’t be authentic unless the bat were real. “I kind of went off my rocker,” he admits in the DVD commentary.

“Shooting the bat drove him crazy,” Zitwer confirms. “He didn’t understand why we couldn’t get a real bat. I tried to explain to him, they have rabies. You can’t control them. I did everything. I called the head bat specialist at the bat zoo. I was prepared to take him over there, bring the guy to the set.” Cage wouldn’t let go. “There was a young production assistant who was assigned just to Nicolas,” Zitwer says. “His name was Osman. He sent Osman to Central Park with an ice cooler and a broom to try and capture a bat. And then Osman told us that Nicolas found out you could get bats from Mexico. Probably illegally, of course. We just said, ‘OK, this is going too far. We’re not gonna FedEx some bat from Mexico.’ Except I think they actually looked into it. That was one time that I recall being extremely contentious.”

Bierman finally persuaded Cage by explaining that if he got bitten by a bat, he would probably die and the film would be ruined.

At 23, Cage already fancied himself a Method actor, and you get the sense he would have happily subjected himself to a bat’s fangs for the sake of this film. He has said that he cared more about that performance than any other in his career. It’s a master class in unbridled bizarreness. Cage saw Vampire’s Kiss as a chance to pursue his own experimental mode of acting, a full-throttle rejection of naturalism that owes as much to 1920s German expressionism as it does opera and slapstick comedy. His onscreen outbursts are legendary. When the script called for him to cry, he challenged himself to literally scream the word “Boohoo!” When the script called for him to rant about a misfiled contract, he delivered “I’ve never misfiled anything!” with all the fervor of a revivalist preacher. This performance is the seedling from which every great Cage-loses-his-shit role—the self-destructive pathos of Leaving Las Vegas, the obsessive-compulsive jitters of Matchstick Men, the campy absurdity of The Wicker Man—subsequently sprouted.

Cage uses the full force of his physicality to convey the character’s insanity. In the film’s most iconic sequence, he not only bellows the entire alphabet but performs increasingly frantic hand movements to accompany each syllable, with Elizabeth Ashley working in perfect counterpart as the exasperated shrink. None of that was random. “It actually is extremely choreographed,” Cage says in the commentary. “Every one of those moves was thought out in my hotel room with my cat.”

To get turned on, Nic asked to have hot yogurt poured over his toes while he was doing a love scene with Jennifer.Associate producer and casting director Marcia Shulman

It’s a common misconception that Cage veered from the script or went apeshit against his director’s wishes. In reality, everything except the cockroach was in the script (“every word,” Minion insists), and Cage and Bierman worked closely together on his surrealistic movements and mounting intensity. It was the director’s idea for Cage to hop onto the desk like a deranged cat when he confronts Alva. “The actual story has got very low stakes,” Bierman explains. “I realized, to keep the story moving, the character that Nic was playing would have to be constantly changing, constantly in a new phase of his derangement, so the audience would never know what they would get.”

When Cage first showed up for the film shoot with a penciled mustache, Bierman convinced him to ditch it. But the director did approve of Peter Loew’s faux-British accent, a pretentious touch that was inspired by Cage’s father, a literature professor. “I’d noticed certain Americans in Britain would speak with this affected accent: a transatlantic cultured accent,” Bierman says. “So when Nic did this, I thought, ‘Oh, this is great. He’s got it exactly right.’”

The producers, however, were horrified; Zitwer remembers thinking, “Oh my God, what the hell is he doing?” She confronted Bierman about the accent during a break, “and Bob said, ‘Nicolas and I have been working on this a lot. We chose this, because if he did the role totally straight, the character is so hateful that it would be unwatchable.’” Indeed, the accent renders Peter’s verbal abuse of Alva cartoonishly funny and quotable, even as we’re repulsed by his rank misogyny and brutality.

When the film was finished, Minion—who had been effectively banned from the set—watched it in a screening room and was astonished. “I was like, Oh my God. He sort of brought it to these heights that exceeded even my expectations in my wildest dreams.”

As for Cage, after he saw the completed film, he left a message on Zitwer’s answering machine saying it had justified his decision to become an actor. His affection hasn’t waned. As recently as 2018, he declared it his “favorite movie I’ve made.”

Part IV: Vampire’s Flop

On the day Vampire’s Kiss was released, 30 years ago this month, Zitwer and Bierman hired a limo and drove around to the few theaters where it was playing. It was a hot day in June. They tried the Beekman Theatre. “There was no one in the theater,” Zitwer says. They tried 42nd Street: All the air conditioners were broken. The AC wasn’t working at the Village East either. “It was a grim experience,” says Bierman. “We went to a theater on the Upper West Side and sat in a half-full screening. The old guy I sat next to had a portable TV on his lap. He didn’t laugh once!” Shulman was so desperate to attract moviegoers, she personally stood at the door handing out plastic fangs.

Nic cost me $10,000 by humming Stravinsky’s Petrushka. The Stravinsky estate was still in copyright. So that’s why we didn’t have any money at the end.Director Robert Bierman

The film was a flop. It didn’t help that Hemdale had kept it on the shelf for 18 months after filming due to drama with distributors. “John Daly really messed up the distribution,” Zitwer says. (Daly died in 2008. Hemdale also requested a number of cuts; Bierman reluctantly agreed to remove one of the therapist scenes.) Adding insult to injury, the company finally released Vampire’s Kiss the same month as Batman—a big-budget juggernaut that grossed more in one night than Vampire’s Kiss earned in its entire run. “All the hype was around Batman. Plus, it’s about bats!” Shils protests. “You’re not going to go to a vampire movie and Batman.”

Critics weren’t receptive. A Washington Post review called it “incoherently bad.” A New York Times critic described it as being “dominated and destroyed by Mr. Cage’s chaotic, self-indulgent performance” and chided Bierman for not keeping his performance under control. “Which was absurd!” says Czapsky. “Because first of all, it was what was great about the film. But also, you couldn’t control Nicolas! He was uncontrollable—in the best way.” Many reviewers seemed unsettled by the film’s violent denouement; Hemdale’s marketing materials presumably did not mention that the protagonist rapes his secretary and longs for death.

Few critics seemed to consider that Cage’s approach was a deliberate rejection of realism rather than clumsy “overacting.” Yet Pauline Kael, the great New Yorker critic, dissented from the pack. “Nicolas Cage is airily amazing here,” Kael wrote, noting that he “does some of the way-out stuff that you love actors in silent movies for doing.”

In fact, Cage’s performance was inspired by silent cinema, particularly Nosferatu (1922), which he mimics with his movements through the club. “I was weaned on German expressionistic films like Nosferatu and Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” Cage says in his audio commentary, “and I wanted to use that kind of silent film style of acting, which, shockingly enough, [Bierman] allowed me to do.” In her book National Treasure: Nicolas Cage, Cage scholar Lindsay Gibb persuasively demonstrates how his cartoonish facial expressions and movements draw on the “presentation style” of silent film. In Vampire’s Kiss, Gibb writes, Cage “was trying to get to a ‘new expression in acting,’ bringing German Expressionism—a high contrast, severe, almost cartoon-like style of acting and filmmaking, which famously rejected realism—into his style.” The famous shot of Peter Loew taunting Alva is a perfect example—Cage communicates as much with his eyes, which he makes outrageously large and leering, as with his words. No wonder that shot works so well as a reaction meme, expressing condescension and faux-surprise.

The commercial failure of Vampire’s Kiss was a small blip for Cage, whose stardom was already assured. But it was personally (and, in some cases, professionally) devastating for the people who’d worked relentlessly to get it made. “After Vampire’s Kiss, I couldn’t get anything going,” says Zitwer. “I would just cry. I would go to the movies and cry, like, why can’t I do this? I love film! I really do.” Vampire’s Kiss had amounted to a brutal education in how difficult and exhausting it is to get a film made at all.

“And then I realized, this is never going to happen again,” Zitwer says. “My film was a bomb. No one saw it. No one cared. I’d say it opened my eyes. What I realized is, I don’t want to be a film producer.” Unwilling to enmesh herself in the corporate gears of Hollywood, Zitwer stayed in New York and switched careers; she launched her own literary agency in 1995.

Before 1989, Bierman had a promising film career in the United States. “Vampire’s Kiss really put the brakes on it quickly,” he says. He shifted over to television work in his native England, where the film had been better received.

I realized, this is never going to happen again. My film was a bomb. No one saw it. No one cared. I’d say it opened my eyes. What I realized is, I don’t want to be a film producer.Barbara Zitwer

Minion did move to Hollywood, where he lived for most of the 1990s, feeling ludicrously out of place. In 1991, Motorama—the film he wrote before Vampire’s Kiss—finally got made, with Shils directing. After that, his luck began to dry up. Meetings with producers made him feel like he was from a different planet. “I don’t have a mainstream sensibility,” he says. “Not a bone in my body.” Minion rebelled against Hollywood culture by writing an aggressively bizarre noirish flick called Trafficking, which he directed with a cast of unknowns in 1997. The movie is distinctly Minion, with an abrasive narrative that grows increasingly warped as its protagonist, a private investigator, loses his mind. Minion considers it part of a loose trilogy that began with After Hours and then Vampire’s Kiss. “I call it the Anxiety Trilogy,” he says. “They all have this quality [of existential anxiety]. I think they got more and more operatic.”

But Trafficking never found a distributor. “I tried and I tried,” Minion says, “until there were no options left.” Nor could he scrounge up financing for postproduction. A rough cut of the film now lives in obscurity on Vimeo. For two decades, Minion has fantasized about finding a way to distribute it; he’s even considered remaking it with a new cast. Mostly, though, he seems to have made peace with the whole nightmare. “That was a new learning phase: ‘This is it. This is the end. You’ve done exactly what you wanted, and it’s not right for this world.’”

When I ask what effect Vampire’s Kiss had on his career, Minion diverges into a lengthy spiel about his filmmaking sensibility and J. Hoberman’s theory of Midnight Movies and his love for transgressive cult films, like the works of George A. Romero. “The people who made those films—you almost got the feeling they were a little bit insane. But in a good way. I loved that! So many times, I feel like things are made by committee and everyone’s too sane.” After Vampire’s Kiss, Minion came to feel that this unhinged aesthetic wasn’t welcome in Hollywood.

Then he stops and remembers my question. “How did it affect me? I dunno. Go ask people who didn’t hire me.”

Part V: Back From the Undead

Last year, Bierman was lecturing at a film school in London. After class, one of his graduate students approached him and said, “I’m very sorry I didn’t ask you questions in class, but I find it a bit overwhelming being in the same room with you.” “What do you mean?” Bierman asked. “You know, you directed Vampire’s Kiss,” the student replied. “It’s just so overwhelming. This is a legend. All we talk about is this movie.”

“He was like a 26-year-old student,” Bierman adds. “I realized that this generation of young filmmakers have seen the film in a completely different way.” Boomers don’t particularly register the movie. But when younger fans realize he directed it, “they react like, Oh my God!”

Bierman has earned the right to some vindication. The film, he believes, was simply ahead of its time: “There are certain scenes that are so modern—the way women are treated in it, sexuality, the problem with personal mental conditions, particularly with young men who have become obsessed.”

Nobody knows exactly when Vampire’s Kiss became a cult favorite. It began during the ’90s, when Jim Carrey was paid millions for the sort of demented slapstick that got Cage vilified. As Cage’s profile rose, Vampire’s Kiss began to make sense as a gateway to the manic side of his career. To whatever extent Cage is known for portraying characters deep in the throes of madness or obsession—for being “unafraid to crawl out on a limb, saw it off and remain suspended in air,” as Roger Ebert put it—Vampire’s Kiss served as the blueprint, inspiring his own self-described “Nouveau Shamanic” discipline of acting.

The film’s reemergence crystallized around the start of this decade. In June 2011, YouTube user “MonkeyGrip100” uploaded a supercut video titled “Nicholas [sic] Cage Freak-Out Montage,” which is four and a half minutes of Cage acting like a lunatic in various films. The entire first minute is taken from Vampire’s Kiss. The video has 959,221 views and counting.

YouTube also serves as a repository for now-legendary snippets of the film—somehow, a nine-second clip of Cage screaming “I’m a vampire!” has half a million views. “It’s almost as if they’re little commercials for the movie on the internet,” Bierman observes. “People can quote to me, word for word, scene for scene. … The film creates a fan base through the bits. And then they go, ‘Oh, what’s the rest of the film like?’” As it turns out, Vampire’s Kiss seems practically tailor made for the surrealist meme age; it just arrived 20 years too soon.

“My kids said that’s the most popular meme at school,” Bierman says. “Someone at school had told them it was a film I had directed. I don’t think they even knew.”

The following year, Vampire’s Kiss received a substantial critical reassessment from then–A.V. Club writer Scott Tobias, who rightly observed that Cage’s performance “raises the question of what good acting really means.” In hindsight, Cage’s subversion of acting norms, and general self-awareness, is more widely understood.

More recently, in 2016, the producers and director celebrated its cultural resurgence by appearing at a Museum of Modern Art screening of the film. Minion was there, too. (He and Bierman have since reconnected and begun working on a new film together, which Minion wrote. Bierman describes it as “a follow-up to Vampire’s Kiss,” though not a sequel: “Think of the Peter Loew character,” Bierman says. “But this time it’s a woman.”)

The film has also amassed a portfolio of famous fans, from Simon Helberg, who delivered a dazzling impression of the alphabet scene on Conan, to Tom Waits, who listed the cockroach moment as one of his favorite movie scenes. During the ’90s, Shulman worked with John Leguizamo and happened to mention Vampire’s Kiss. “He was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s my favorite movie—I watch it every week!’” Shulman recalls.

Cage, to his credit, seemed to have a prescient sense for the film’s eventual cult destiny even before it came out. Speaking to Spin in 1988 (when it was still caught in distributor purgatory), he mused about its outré appeal. “Even if the worst happens and it doesn’t come out for some reason, it’s a movie with integrity,” he said. “Someone’s going to see it and want to see it again. Maybe it can become a rare movie, like a bootleg record.” He even offered a preemptive response to the haters: “I act for myself. I did Vampire’s Kiss for myself. It was something I had to do whether or not people liked it.”

Around 1996, Shils encountered Cage at an AFI event honoring him. By this point, he had won an Oscar for Leaving Las Vegas; the critics who’d scoffed at his weird voice in Peggy Sue Got Married or dismissed his antics in Vampire’s Kiss now had to take him seriously. Cage recognized the producer and instantly began rhapsodizing about the experience.

“Nic used to say to me, ‘Vampire’s Kiss was like my laboratory for these big studio pictures! That was my laboratory!’” Shils recalls. “He really loved the film. Loved making it. And he was able to explore some crazy shit.”

Zach Schonfeld is a freelance journalist and writer based in New York. He was formerly a senior writer at Newsweek.