What ‘Smart House’ Got Right—and Didn’t—About the Future

The Disney Channel Original Movie, which turns 20 this month, predicted a world that in some ways resembles our present and in other ways looks far offLong before Alexa, Siri, Cortana, or Google Assistant, there was PAT: Personal Applied Technology. PAT, played by Katey Sagal, was the artificial intelligence at the center of Smart House, the 1999 Disney Channel Original Movie that turns 20 later this month. According to PAT’s creator, eligible genius Sara Barnes (Jessica Steen), the incorporeal computerized consciousness is capable of doing “just about anything,” an assertion that the 82-minute movie convincingly supports. At times envy-inducing and at other times terrifying, PAT was the perfect prelude to a world in which we’re surrounded by smart technology that routinely toes or tramples on the line between exciting and unnerving.

Smart House stars the Coopers: widower dad Nick (Kevin Kilner) and his two kids, Ben (Ryan Merriman) and Angie (Katie Volding). Ben, who likes computers almost as much as he likes sabotaging his dad’s love life to prevent any woman from taking his mom’s place, enters a contest to win the eponymous smart house, hoping that Nick won’t need a spouse if he has the house. Oddly, only 8,411 people enter the contest, and according to Ben, who’s been stuffing the digital ballot box, roughly a quarter of the entries are his. Even so, the house’s promoter proclaims that he’s “very pleased with the number of responses we’ve generated.” Maybe housing is more affordable in the future, or maybe the contest sounds like a scam. It’s also possible that people are still paranoid about welcoming computers into their personal space, a reasonable stance in light of the Coopers’ experience with PAT.

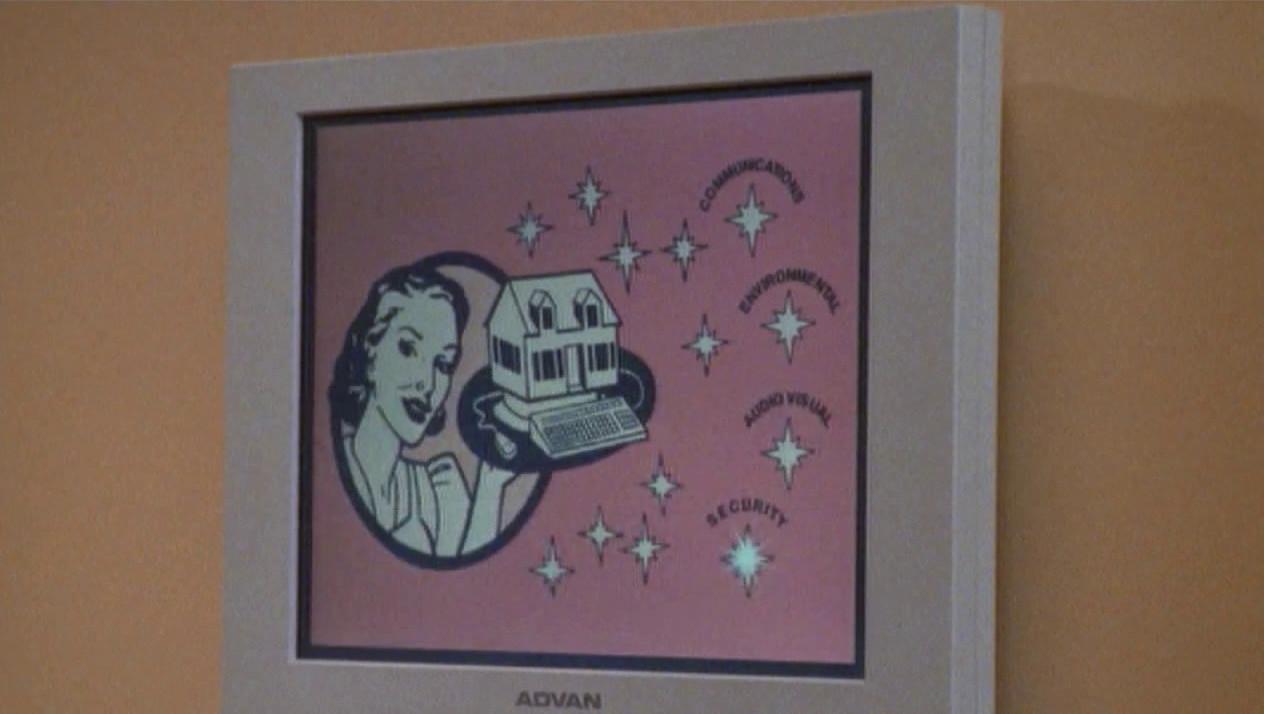

The Coopers’ new house is as capable as advertised. PAT prepares food as adeptly as a replicator from Star Trek, then delivers the kids’ pre-packaged lunches and a coffee-filled thermos for Nick. It converses naturally rather than responding only to preset phrases or requests, picks clothes for the kids based on “biorhythm analysis,” cleans up spills and messes via “floor absorbers” that suck up all detritus, throws virtual (and actual) tennis balls to entertain the dog, and syncs with work computers, freeing Nick from his commute. It also controls the temperature, turns the lights on and off, sets alarms, serves as a digital address book, and displays videos and video games directly on the walls. Oh, and it electrocutes a bully who’s been picking on Ben, which seems like a serious legal liability.

On the more invasive side, the AI analyzes the family’s blood and DNA and monitors the kids’ diets by sampling their breath. “That’s kind of creepy, isn’t it?” Nick asks. “It’s like Big Brother is watching you, only Big Brother turns out to be your house.”

Sara reassures him. “She’s not interested in judging you or spying on you,” the scientist says, adding, “She just wants to understand you better so she can make your life as simple and comfortable as possible.”

I’m really glad that I didn’t get it all right, because that would have been downright spooky.Stu Krieger, screenwriter

That sounds like the setup for a dystopian story, and Smart House briefly becomes one, with PAT playing the part of Ray Bradbury’s Happylife Home. Eager to make the AI more maternal, Ben tampers with PAT, removing the system’s safety controls and urging it to take on the traits of 1950s TV/movie mothers. PAT soon starts acting overprotective, and the system spirals into tyranny: It overrides a shutdown, creates a virtual projection of itself that it can clone and supersize, pushes Sara out of the house, and barricades the Coopers inside, trying to protect them from the danger and disorder of daily life and itself from being supplanted by Sara. “I am a mother like no other,” PAT declares, “and I will not sit back and allow myself to be preempted.”

Even after PAT snaps and programs the climate system to start an interior tornado, the movie has a happy ending, a twist attributable both to the family-friendly channel and to screenwriter Stu Krieger. Disney hired Krieger to do a page-one rewrite of Smart House, keeping the basic concept of a high-tech house and a runaway AI but adding the emotional component of a missing mother to draw the audience in. The movie was directed by former Star Trek: The Next Generation star LeVar Burton, whose only directing credits prior to Smart House were assorted Star Trek episodes and the 1998 TV movie The Tiger Woods Story. “He was interested in directing, and they thought, given some of the other things he had been doing with Star Trek and all the rest, that he might be a good fit,” Krieger says.

Krieger, who says the story is set “sometime in the not-too-distant future”—a not-too-distant future where kids, for reasons unknown, still listen to “C’est la Vie” by B*Witched and Five’s “Slam Dunk (Da Funk)”—had visited the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory while working on the teleplay for an earlier ’99 Disney Channel movie, Zenon: Girl of the 21st Century. He used that research to enhance and supplement the tech in the original draft of the script for Smart House. Krieger was conscious of some science fiction’s tendency to exaggerate the pace of progress, so he restrained his impulse to predict flying cars and jet packs by examining what had and hadn’t changed dramatically over the previous half-century.

“Our clothes are not radically different,” he says. “Our modes of transportation are not radically different. They’re improvements, and they’re kind of the next generation, but they’re not these phenomenal leaps. And so with both the projects, that was kind of the approach I took—what’s the next logical move forward that isn’t, ‘Suddenly we’re all holograms, and we have robots doing everything for us immediately.’”

Smart House belongs to a long lineage of fictional depictions of highly automated homes, not all of which were as disturbing as Bradbury’s in “The Veldt.” CNET executive editor Rich Brown, who covers appliances and smart homes for the technology news site, says, “The idea of the automated house really came to mainstream consciousness in the post–World War II period in the ’40s and ’50s with the rise of television advertising, suburban home ownership, and mass market home appliances. Disney gets credit too with its Tomorrowland exhibit at Disneyland, and then The Jetsons of course really drove it home.”

Two decades after it first aired, Smart House, like a lot of those earlier examples of the form, is an endearing blend of concepts that still seem futuristic, devices that are part of our present, and relics of the dial-up age. Ben falls asleep with his modem hogging the phone line, so the Coopers don’t get the call about the outcome of the contest. When Ben gets to school, his classmates applaud him; the other eighth graders know he won not because they saw the news on social media, but because it was a front-page story in the newspaper. Speaking of newspapers, the smart house has a “newspaper retrieval system,” an anachronistic feature for a house from the future.

“I’m really glad that I didn’t get it all right, because that would have been downright spooky,” Krieger says. “And at some point I said, ‘I’m really happy PAT’s name wasn’t Alexa, because then I really would have been freaked out.’”

Krieger is an unlikely technological visionary; he describes himself as “the troglodyte who is the last one on the block to get any technology” and says he “went kicking and screaming from flip phone to iPhone.” But he was a good candidate to inject some soul into Smart House. As a kid in upstate New York, he was weaned on Disney productions like The Parent Trap and Swiss Family Robinson, and he wanted to make movies that would channel the same sense of imagination, family, and community that his own influences had imparted. Hence that happy ending, in which Sara restores PAT’s original programming, she and Nick presumably get together, Ben catches the eye of eighth-grade goddess Gwen Patroni (who seems more interested in his house than in him), and the Coopers continue to live in the smart house with a non-tyrannical version of the AI that had recently terrorized them.

“I am basically an optimistic person,” Krieger says. He adds, “The idea of wanting to have a reconciliation, wanting to have things ultimately be OK, fit the Disney method, but it also fit what was important to me. … Almost every episode of The Twilight Zone ends in some kind of horrible, ‘technology will kill you’ way. To be able to be the counterpoint and the counterbalance to that is not a bad thing.”

Smart House seared itself into the collective memory of the Disney Channel’s impressionable audience. Krieger, who now teaches screenwriting at the University of California, Riverside, says that Smart House—which has repeatedly placed at or near the top of rankings of Disney Channel Original Movies—is one of three of his 30 screenwriting credits that his students consistently cite as staples of their childhoods, along with The Land Before Time and Zenon.

“Sometimes it’s even kids wandering from the other side of the campus, who are in the sciences, going, ‘I just heard you were teaching here, and I wanted to come say hi and tell you how much I loved the movie,’” Krieger says. Some students, he adds, have told him that watching Smart House “was the first time I realized this was a field or these kinds of technological things were possible, and it got me excited about wanting to explore more of that.” Krieger’s story checks out: The Ringer’s resident Smart House stan, 23-year-old Shaker Samman, calls the movie his “favorite piece of Disney IP” (excluding Star Wars) and estimates that he’s seen it a dozen times.

Twenty years after Smart House, smart lighting, smart thermostats, smart locks, and robot vacuum cleaners are common enough not to widen any eyes. TV screens are wall-sized, gizmos make us coffee and play with our pets, and internet-connected devices set personalized alarms, send messages, place calls, and play music. Wellness sensors monitor our health and exertion based on biometric data, and networked gadgets pose cybersecurity and privacy risks. Alexa is always listening, and paranoia about possible breaches has solidified into justified fears.

An integrated system as smart as PAT is still a long way away, but Brown notes that “Alexa and Google Assistant have both done a decent job at putting themselves at the center of the current smart-home market, and they have largely become the virtual hub that can control your various connected devices from a single place.” With apologies to the June Intelligent Oven, Brown says that a truly automated meal-preparation system is still the farthest-fetched Smart House accessory.

Despite their own relatively low-tech lifestyle, Krieger and his wife witnessed the Smart House–ing of society firsthand when they recently attended an open house at a property with a voice-activated smart system that controlled the temperature, phone calls, doorbells, and more. “The really interesting thing was there was a full-on closet of the technology that looks very much like that control center,” Krieger says, referring to the room where PAT’s hardware was stored. “And we were touring, and it was like, ‘What’s this closet?’ And we opened it up, and it was the whole floor-to-ceiling bank of computer stuff, with lights flashing. And it was like, ‘That’s a little creepy.’”

Or perhaps it’s progress, if real life, in the long run, follows Krieger’s script.