“For when you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

—Friedrich Nietzsche

“German people, I think, have exotic ideas about dessert.”

—Chris Ryan

1

My favorite TV shows are the ones that combine extreme, clinical, dead-eyed, soul-flattening depression with a passionate dedication to 4K HDR. You know these shows: Often but not always European, they feature moody wide shots of search parties combing barley fields for missing teens while raspy Scandinavian electro-turtleneck ballads underscore both the futility of their quest and the clarity of every barley stalk. They feature sad-eyed detectives named Uwe who chain-smoke on wintry beaches while contemplating the horror of human cruelty. They feature slowly scrolling overhead shots of trees. They feature villages where everyone has a secret. They feature Volvos. They feature rain rendered with such diamond precision you remember how great your TV looked when you picked it out at Best Buy. They feature sweaters, and they feature slow motion, and, when things really get wild, they feature sweaters and slow motion at the same time.

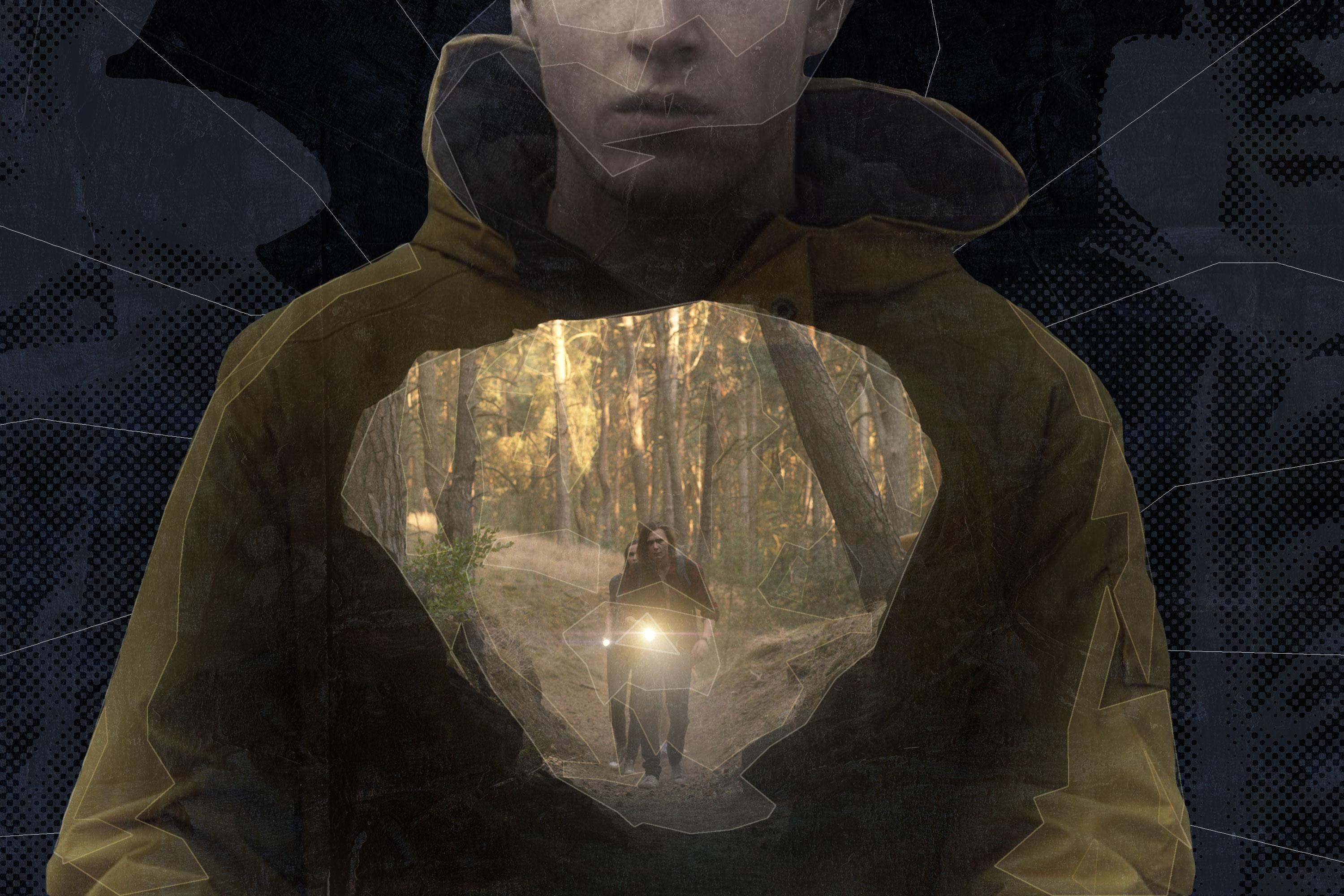

Dark, the outstanding German time-travel thriller whose second season recently premiered on Netflix, takes this gloomy-screensaver vibe further than maybe any other show I’ve ever seen. The show revolves around—well, the show has one of the most floridly complicated plots of any series on TV, but the ultra-ultra-elevator pitch version is that it is an intimate domestic drama about four interconnected families in a small German forest town and how their lives change when a temporal rift in a nearby cavern causes several of them to either disappear or become warring timelords. It looks exactly like this sounds. Most of the humans are sad sacks; most of the environments look like they were rendered as part of a proof-of-concept video to make Christopher Nolan invest in a drone. It’s a show about despairing, broken people living in a Retina display with shitty weather. It’s so good. The yellow rain slicker worn in Season 1 by the teen protagonist, Jonas Kahnwald, looked so incredible against the deep-forest-social-democracy backdrop that I—neither a rain slicker aficionado nor, if I’m honest, a teen—found myself wishing that I could also be under 20 and damp in the vicinity of a mysterious nuclear power plant.

What I’m getting at here is that Dark is a show whose entire visual aesthetic seems to suggest

9

Thirdly, the interesting thing about time-travel stories is that they love to play games with information. This is an area where Dark is especially brilliant. That is to say, Dark is messing with you, mercilessly, at every moment, and the medium it has chosen for doing so is constant temporal jumps. From a storytelling perspective, skipping forward and backward across multiple timelines is an ideal way to manipulate the sequence in which viewers receive the key facts that make up a narrative. You can leave suggestive gaps wherever you want, because, hey, time travel. You can show things out of order, on the grounds of time travel. You can break scenes off at the most provocative possible instant—that’s time travel, my friends. You can keep your viewers confused and guessing, for time-travel-associated reasons, and then pick the most devastating moment to reveal that the person the assassin has been sent back to kill is

4

Do you know what I mean? Some shows are hypercommitted to being themselves. This is a quality strongly correlated to, but not identical with, originality. CBS’s NCIS, a standard police procedural, is about 60 percent itself. HBO’s Deadwood, a series about people who love to use profanity near cow shit, and how this is the true origin of civilization, is 135 percent itself. Dark is 43 billion percent itself. It has, conservatively, several thousand characters, each of whom is played at multiple ages by different actors, often in Jesus beards and mysterious hoods. It has ornate, golden clockwork machines that whir open and make wormholes appear. It is chock-full of dialogue like (I’m quoting from memory) “Did you not realize, professor, that the fallacy of time and the fallacy of free will are intertwined, to man’s unending cost?” (This is spoken by a 9-year-old girl while the camera pans bleakly across a display case full of chess pieces, probably.) It has secret Latin codes. It has evil time-traveling priests. It has bug-eyed clockmakers whose obscure books on the nature of temporality hold the key to predicting what will happen.

It has all this stuff, and it not only refuses to apologize for any of it or play distancing postmodern irony games with it, the show absolutely revels in all of it. At times the effect is less “TV series” than “intricately plotted graphic novel unconcerned with appealing to anyone except hardcore fans.” It is high on its own supply of unhappy townsfolk in rain gear battling evil across four dimensions, and this is somehow pretty great even if, like me, you don’t really read graphic novels or enjoy long, spiraling theoretical conversations about the nature of

NCIS is about 60 percent itself. Deadwood, a series about people who love to use profanity near cow shit, and how this is the true origin of civilization, is 135 percent itself. Dark is 43 billion percent itself.

12

an idea of what I’m talking about. The first thing you see in the first episode of Season 2 is an epigraph from Nietzsche. If you’ve been boning up on the migraine-kindling intricacies of the plot of Season 1, you might be thinking, “that which does not kill us makes us stronger,” but no: It’s the one about how if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you. The first line of dialogue, spoken by a sweaty, shirtless man pounding a hammer against the wall of an underground tunnel, is: “The beginning … and the end. A strange idea that both should be the same.” The second line of dialogue, spoken by another shirtless man in the same tunnel, is “Sic mundus creatus est.” For when you gaze long into a Silver Surfer comic, the Silver Surfer comic gazes also into your Final Draft 11 document.

We are not 10 minutes into Season 2’s first episode before we see our first wall covered with clues connected by bits of colored string. I didn’t keep track of how many walls covered with clues connected by bits of colored string Dark offers overall—between seasons 1 and 2, I’d put the over/under at 12, I think?—but it’s a

15

When the first season of Dark hit Netflix back in 2017, the show was almost universally described as “the German Stranger Things.” On one level, that comparison makes sense. Both series involve supernatural mysteries opening out around the disappearance of a child. Both series move among a group of interconnected families in a small town. On another level, however, this is a terrible comparison, because—meaning no disrespect to Stranger Things—Stranger Things sucks and Dark is way better than it.

OK, yes, that’s an exaggeration. Stranger Things does not suck, per se. It’s pleasant to watch. I enjoy it! I just can’t shake the feeling whenever I watch it that I am shopping at a Nordstrom Rack of the imagination: narrative garments designed and crafted by someone else, piled indiscriminately into bins to be sold at a discount. Here’s a three-pack of Ralph Lauren underwear; here’s a 50-pack of easy ’80s references. Nordstrom Rack can be a great place to shop, but you’re there to find familiar brands on the cheap and you know it. Dark, too, loves a well-worn narrative trope, but Dark’s approach is more like “Welcome to our underground boutique of deconstructed workwear refined to the obsessive standards of an exacting subculture; please feel free to look around although you cannot afford to buy anything.”

6

Which might not seem like a good fit for a streaming service? After all, Netflix shows tend to be designed for casual consumption, largely by people who are simultaneously consuming something both closer and more hypnotic, i.e., whatever boring thing happens to be on their iPhones. You cannot consume Dark casually or while looking at your iPhone because it is too complex, and when you glance back at the TV you will be so confused that you have to call 911, be rushed to the hospital, and perhaps die.

Still, it’s possible that Dark is itself evidence of a different phenomenon. Maybe what’s actually going on is not that streaming is making shows less complex, but that streaming is encouraging a radical polarization of ambition. Shows are either deliberately throwaway, designed to be buzzed about for a week and then forgotten forever, or else the amorphous goals of their corporate overlords mean that they’re liberated to plunge into their own bizarre creative visions. (I think of this as the “me, when I worked for ESPN” model of content creation.) And maybe, in that case, they’re sometimes liberated even when their visions seemingly revolve, as with Dark, around a private canon of high-resolution cavern photography, sorrowful mustaches, and secret societies waging parallel shadow wars across multiple eras of human history at once. (Also me when I worked for ESPN, obviously.)

11

One such extreme contrast, in Dark’s case, is between the complexity of the plot (phenomenal) and the quantity of attention likely to be devoted to it by the average Netflix viewer (maybe slightly less than phenomenal considering that you got three notifications while reading this sentence). Another is between the texture of the lived reality the show presents and the fancifulness of the mythology surrounding it. The texture of reality in Dark is very real. The roads have potholes. Men wear bad ties. The chairs in auditoriums, where angry townspeople assemble to yell at police during public meetings, squeak precisely as they would in real life if anyone actually went to public meetings. The fluorescent light in the nuclear lab is not just regular fluorescent light but ultra-HD fluorescent light, enabling you to contemplate its essential fluorescent-ness unencumbered by the limitations of obsolete technology (1080p). People suffer through bad marriages. They smoke too much. Parents and children don’t understand each other. Everyone is hiding something. All this feels mostly true to the real world. At the same time, though, the show’s myth-arc of warring time-jumpers and their Jedi hoods is so over the top that half the pleasure of watching lies in seeing just how seriously it’ll have the nerve to take it. Let me give you

13

lot of walls covered by clues connected by bits of colored string. One of the bunkers is in a postapocalyptic wasteland, which is reassuring in a way? The world can implode, but people will still round up some tape and string. You’d hate for the fall of civilization to mean the end of crafting.

17

In other words, maybe it’s the streaming economy itself that’s enabling this ramping up of contrasts? Perhaps we can throw ourselves into spectacularly elaborate narratives not so much despite the delivery mechanism as because of it—because an atmosphere of profound complexity is enjoyable even when we don’t follow all of it, and because putting in the work to follow the scrambled timeline is itself a thrilling novelty on the platform that gave us Fuller House. Maybe we can accept the coexistence of pie-in-the-sky time-warrior magic and mundanely depressed small-town Germans in one narrative because an ecosystem that crams all our entertainment options in one place primes us to accept ever more extreme juxtapositions.

I’m not really sure, and in this, I am unlike the creators of Dark, who are sure of absolutely everything, from the intricacies of theoretical astrophysics to the nature of free will to the pros and cons of H2No vs. Gore-Tex. I’m just glad Dark exists. There should be more TV shows this unflinchingly devoted to exploring their own fantasies, as opposed to reheating older ones. There should be more TV shows this willing to trust their audiences. There should be more TV shows this eager to devote tens of millions of pixels to people looking resigned while steering station wagons into parking lots. Sic mundus creatus est, and please, don’t forget to turn off motion smoothing.