Sufjan Stevens and the Curious Case of the Missing 48 States

More than 15 years ago, a young indie folk artist set a course to traverse the United States of America through song, accruing acclaim, a fan base, and lots of anticipation along the way. Or did he?Part I: The Great Lakes State

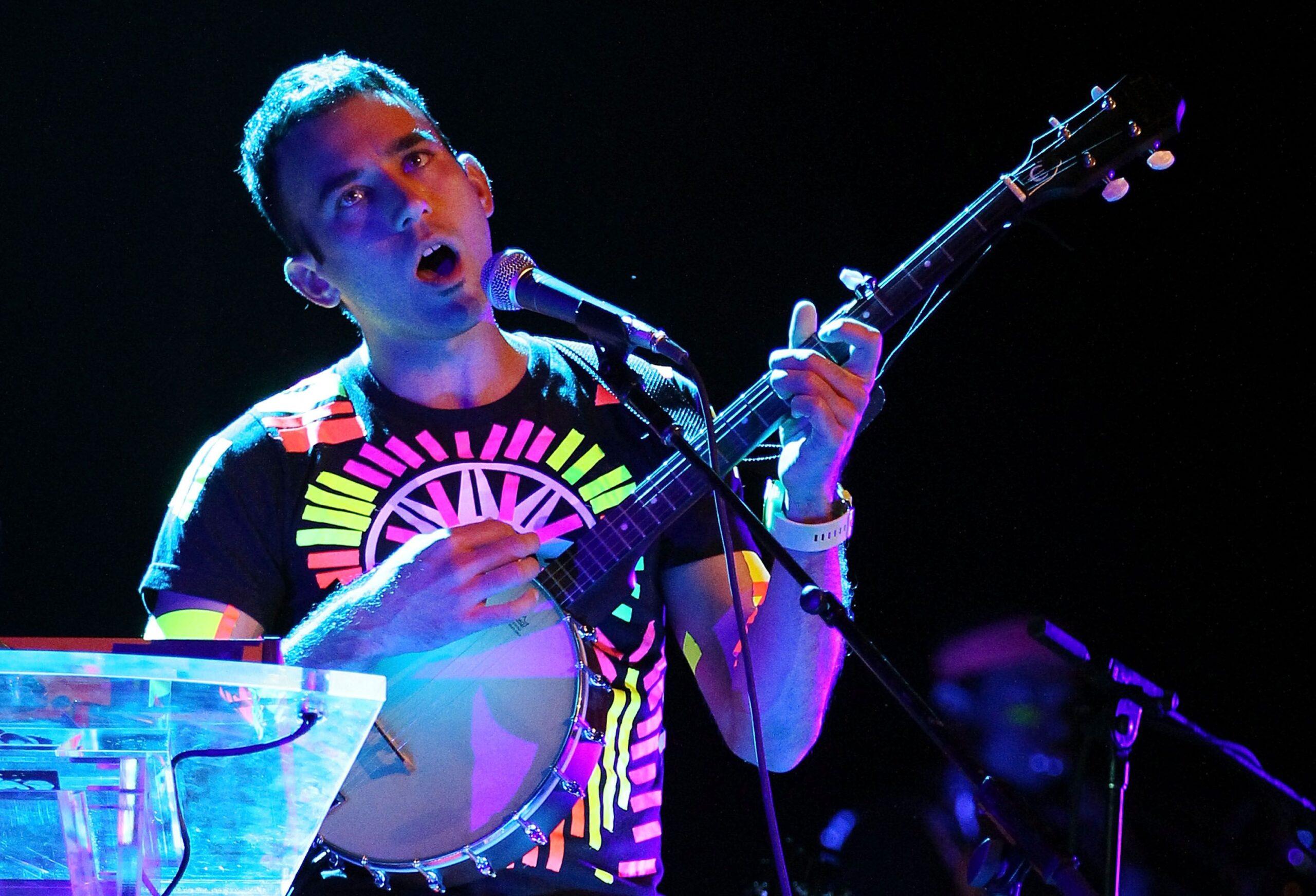

Remember when indie rock turned into a whimsical, state-by-state geography lesson? Sufjan Stevens was our banjo-plucking pied piper, traversing the map while delivering two outlandishly baroque masterpieces about specific U.S. states. First came Michigan. Then Illinois. Then Illinois again, sort of. And then—well, we’re still waiting.

Michigan and Illinois seemed to unite the whole cynical swath of music lovers: Here were two kid-friendly, parent-friendly, grandparent-friendly concept albums capable of topping Pitchfork’s year-end lists and delighting your history teacher all at once. Yet by the last decade’s end, the singer’s overarching conceit had been mysteriously abandoned: Sufjan Stevens did not write and record an album about all 50 states. He didn’t even make it out of the Great Lakes region. No wonder millennials have trust issues.

I was reminded of the 50 states project recently while traveling through Michigan. As I passed Ypsilanti and Romulus—names familiar to me, I confess, because of Sufjan Stevens—I couldn’t resist revisiting the singer’s tribute to his home state. Then I thought of the years I spent waiting for 48 more state albums, and I wrote a silly tweet. It touched a nerve. “This hits hard,” one fan responded. “I even paid to see him dance in neon in 2010 cause I craved that sweet sweet Dakotas double album that never was.” I’d tapped into a diaspora of Sufjan fans, of people who’d spent their college years sipping Natty Light while secretly wondering when the singer might tackle Alabama.

My subsequent investigation has undercovered indie-folk corruption of the most galling degree: Stevens never really planned on recording 50 state albums. That was a joke. We were duped, our trust stolen in an audacious act of grand theft banjo. (Stevens was not available for comment for this article, and while I’d love to tell you that is because he is busy conducting scrupulous research into Delaware, that’s just wishful thinking.)

It’s hard to stay mad. Without this absurd PR stunt, two of the greatest indie-pop albums of the 2000s might never have been heard by a wide audience. That they were is largely a testament to Daniel Gill and Marie VanAssendelft, the two publicists who worked on Michigan. The untold story begins in 2002, when Gill briefly became Stevens’s manager. Back then, Stevens was a little-known 27-year-old songwriter from Michigan, a skilled multi-instrumentalist with a wispy voice and unabashed Christian faith. He had two albums under his belt and a close association with the indie-pop sibling outfit Danielson Family, but did not, by most measures, seem headed for household-name status.

Then came a kernel of an idea. In late 2002, Gill took Stevens to dinner at a Chinese restaurant in New York. They chatted about the songwriter’s budding career. Stevens mentioned he was working on two albums: one he wrote on piano—a concept album about Michigan—and another he wrote on banjo, which became Seven Swans. “I was like, ‘OK, you’re doing a concept album about the state of Michigan. Why don’t we just say in the press announcement that you’re going to do an album about all 50 states?’” Gill says. “It seemed like such a ludicrous idea. Because even if he puts out an album a year—which is ambitious—it would take 50 years. And he was already in his late 20s. We were all like, ‘No one’s really going to believe that you’re gonna do this. People won’t take it that seriously.’”

Stevens liked the idea—even if he had zero intention of making 50 albums. He has admitted as much in later years. “I have no qualms about admitting it was a promotional gimmick,” he said in 2009.

“From my perspective, it was like: Let’s just try to get you some attention,” Gill says. “At the time, he had no fan base. No one was paying attention.”

When Michigan (sometimes styled as Greetings From Michigan: The Great Lakes State) was completed in 2003, it was clear that there was something worth paying attention to. The record is fantastic: a sprawling and melancholy song cycle rich with geographic references and compositional eccentricities. But not many knew who Stevens was. “We were struggling, as most music publicists do sometimes, where you know you have an amazing album but just trying to get people to listen to it is super difficult,” says VanAssendelft, then a senior publicist at the music marketing firm Fanatic Promotion. “That’s where we really just pushed forward this 50 states [concept]. ... It was definitely what we used as a hook, in addition to ‘This is a great album.’”

As for actually completing the project, “I think we all knew that was never happening,” VanAssendelft says. But Stevens seemed excited by the prospect of people hearing his music.

The PR team chose to emphasize Stevens’s supposed (read: fictitious) bid to cover all 50 states in his bio and press packet. When people asked whether Stevens was serious, Gill would never give a straight answer. “It was definitely a PR stunt,” Gill says. “He knew it and I knew it.” But journalists were intrigued. “Their first question was, ‘Well, what state is next?’” VanAssendelft recalls. “Because we knew he would eventually be putting out an album about Illinois, that … gave it credibility.” (Gill remembers differently—he says they did not know Stevens would do a second state until later.)

The tipping point came in late July. Pitchfork, the increasingly influential arbiter of indie (full disclosure: I am a contributor there), had given the album a lukewarm review—“a 7.5,” Gill claims, “and it wasn’t Best New Music.” Except the site’s top editor, Ryan Schreiber, had not actually heard it. “We were bugging him to actually listen to it. And then he listened to it and he freaked out and he was like, ‘I can’t believe we gave this album a 7.5,’” Gill says.

What happened next is a matter of some disagreement. According to Gill’s recollection, Schreiber deleted the original review, reassigned it, and published a far more glowing endorsement, with a Best New Music designation and an 8.5 score. Schreiber, however, says he simply republished the same review but tweaked the score. “The review had been sent to me by the writer, Brandon Stosuy, on a night when I was short on material for the next day, and I didn’t have a chance to listen before publishing,” Schreiber says in an email. “I think the score was originally a high 7 or flat 8. Over the weekend, I fell completely in love with the record and asked Brandon for his thoughts on republishing the review with a higher score.” The copy, Schreiber says, was unchanged; the original review does not appear to be archived on Wayback Machine today. Stosuy did not respond to a request for comment.

In any case, word got out. “Once they re-reviewed it, I remember getting calls like, ‘Hey, can you send me that album’—which I had sent, like, three times,” VanAssendelft says with a laugh. Subsequent reviews mentioned that this guy was recording 50 albums about 50 states, spreading the information to newly converted fans. An Irish Times review declared it “the beginning of a career-long project.”

Months before names like Joanna Newsom and “freak-folk” lit up blog comment threads, Stevens was a minor sensation. Here was a Christian singer with an odd first name who made it cool for indie rockers to put down their Pavement and pick up a banjo. On tour, the singer’s shows grew bigger, his crowds more rapturous. “The devotion is the thing that really struck me,” says John Thomas Robinette III, who played drums on the Michigan tour. “It wasn’t the head-bopping type of devotion. It was, ‘I’m going to do whatever it takes to get into the green room after the show to hang out with this guy.’” Robinette had never seen anything like it.

Part II: The Prairie State

Despite the success of Michigan, Stevens did not immediately lean into the 50 states concept. Instead, he quickly followed that album with Seven Swans, a small-scale folk record with a biblical motif and no discernible songs about U.S. states. It was well-received, if not what fans of Michigan had expected.

“I was trying hard to convince him to change the name of Seven Swans and make it a state album,” Gill says. “It doesn’t make any sense. Why would you put out another album right afterwards and not make it about a state? He was like, ‘Well, it’s not about a state.’ I was like, ‘Who cares? Let’s just call it New Jersey or whatever.’ He was like, ‘No, no.’ He fought me on it for sure. He was like, ‘There’s no way I’m gonna make this album a state album.’”

“I think he thought it was funny to release Michigan and quickly follow it up with an album that’s not a state album,” Gill adds. “He likes to play with the audience a little bit.”

Stevens’s prolific drive was astonishing. By the time Swans was released, in March 2004, he was already at work on songs about Illinois, the next target in his star-spangled geography lesson. Why Illinois? “I feel like specifically Illinois and Chicago are sort of the center of gravity for the American Midwest,” Stevens later told Dusted Magazine. He was attracted to the Midwest because it was where he’d grown up. But he planned to branch out. “I think my next state will definitely be in a different region, a different time zone,” he said. (When asked if he’d really cover all 50, he kept it vague: “That’s the intention, we’ll see how far I get,” he told The Guardian.)

In April, Stevens played an early version of “Chicago,” Illinois’s centerpiece-to-be, during a show at New York’s Knitting Factory. The 2006 Danielson Family documentary captures the moment: Stevens tentatively strumming the tune backstage, then debuting the future classic in front of an adoring crowd. “The saying goes that I am recording a record for each of the 50 states,” he tells the audience (a coy choice of words). “Seven Swans is a little break from that. Now that we’ve had time to breathe and reassess the entire project, I’m moving on. We’re gonna end our set with a song from a record I’m working on now called Illinois.” The crowd cheers, thrilled to be let in on this little secret. In the documentary, this leads into a montage of press clippings signifying Stevens’s newfound stardom. One headline proclaims: “The 50 States of Rock.”

That year the singer flung himself into research about Illinois: visiting towns, reading biographies of Abraham Lincoln, studying early immigration records, even browsing local newspapers and police logs. While Michigan drew heavily on Stevens’s personal experiences in that state, Illinois spanned outward. “He just went all in, studying the entire history of the state,” says Craig Montoro, who played trumpet on the album and tour. “In retrospect, that was another giveaway that this was either going to be a lifelong pursuit—he’d be near death by the time he got to the 50th state—or maybe it wasn’t gonna happen.” According to Montoro, this became a running joke among Stevens’s bandmates: “How was he gonna finish this? How old was he gonna be? Which joints would have been replaced.”

If Michigan was ambitious, Illinois was doubly so: a 74-minute symphonic fever dream outfitted with oboes, glockenspiels, sleigh bells, and dramatic overtures. The arrangements were bolder, the song titles lengthier, the time signatures weirder, the emotional stakes higher. The record’s investment in local history ran deep, with sad songs about UFO sightings and John Wayne Gacy Jr. holding court with rousing sing-alongs about Andrew Jackson. Lincoln, of course, was mentioned. That a certain other Illinois senator began capturing headlines and presidential speculation around the time it was released was so perfect you’d think Stevens planned it.

Upon release (during the week of July 4, no less), Illinois was roundly hailed as a masterpiece. Pitchfork did not waffle this time; Amanda Petrusich awarded it a 9.2, calling it “a staggering collection of impeccably arranged American tribute songs.” “Illinois got the best press of any album I’ve ever worked in my career by far,” Gill says. “It was just ridiculous. Pretty much everyone said it was the best album of the year.” (Indeed, Pitchfork, Stereogum, and NPR all crowned it as such.)

Midwestern fans were particularly moved. “Sufjan always felt like an especially important musician that the entirety of the Midwest could claim,” says Aaron Calvin, a longtime fan from Iowa. “Especially since he seemed so interested in elevating Midwestern stories that took place in those specific settings. Growing up in Iowa, it always felt fun to imagine him writing a song about a small town in Iowa because it seemed very possible.”

The singer’s runaway success was surely a function of his ability to write songs that were as emotionally resonant as they were musically and textually intricate. But the gimmick helped. How could it not? In the absence of a fluke hit, indie rock requires a hustle to break through; in some cases, it needs to be “eventized” to be noticed on a wider scale. The imaginative sprawl of the 50 states project promised the former and delivered the latter. It was, for many listeners, genuinely irresistible.

Stevens was more popular than had ever seemed possible, but he remained press-shy. “Letterman and Conan were calling me all the time, like, ‘When can we get Sufjan on the show?’” Gill says. “And he didn’t want to do it. He thought it was crass or something to play on TV.” The singer did submit to non-televised interviews, and the 50 states project was a frequent topic of questioning, given that journalists now took it quite seriously. In a chat with Dusted Magazine, Stevens waxed philosophical about American identity and songwriting. “The states themselves are just kind of the fabric,” he said. “They’re kind of the canvas, and they create very helpful arbitrary guidelines.” Speaking to The A.V. Club in July 2005, he was surprisingly candid: “I’ll admit that it’s all advertising, and all gimmick,” he confessed. “Initially, it was intended just to get attention.”

If that was meant as a veiled admission that he wouldn’t complete an album for all 50 states, the message was not received. During the fall tour, Stevens and his band wore University of Illinois cheerleading outfits. They even opened shows with “The 50 States Song,” a joyous theme song that mentioned every state by name. “Fans were coming to the shows and bringing him stuff about their home state,” Gill recalls. “Like: ‘Here’s an idea for when you do my state’; ‘Here’s a book I think you should read when you do Utah.’ It was crazy. I think I went to three of the California shows—people were like, ‘You have to do California next!’”

He just went all in, studying the entire history of the state. In retrospect, that was another giveaway that this was either going to be a lifelong pursuit or maybe it wasn’t gonna happen.Craig Montoro, musician

The speculation carried over to Stevens’s backing band. “It kinda was a contest among us to try to influence what the next state would be,” Montoro says. “I’m from Texas; I was trying to push him towards that. Other people were like, ‘What about Washington state?’ They were trying to sneak in a little influence in case his mind wasn’t made up.” Band members got in the habit of finding state quarters for Stevens and even gifted him a map of the 50 states where you could plug each state’s quarter into a corresponding hole. “Every time somebody would get a quarter with a state on it, we would say, ‘Oh, hey, does he have this one yet?’ We were all in. Everybody believed it.”

Tom Eaton, who contributed trumpet to Michigan and backing vocals to Illinois, was more skeptical. “I sensed kind of an ambivalence about it,” he says of the 50 states conceit. “I had a hard time seeing him locking himself into that specific project for the next 75 years.”

Part III: The Unsung States

Which state was next? A bluegrass album for Kentucky? A gritty, Lou Reed–inspired New York opus?

After Illinois, fans and journalists were eager to speculate, and Stevens seemed happy to join in.

“He played along with the 50 states thing to an amazing degree,” Gill says. “He was going to launch this website—I think he bought the URL, like The50States.com. It was an interactive map of America.” The project never got off the ground. At some point, Gill even floated the idea of outsourcing smaller states to other acts on the Asthmatic Kitty roster: “Every time there was a new Asthmatic Kitty signing, I was like, ‘Just have them do a state album and farm it out!’” But that idea never took.

In a clever segment, NPR convinced Stevens to come up with a song about Arkansas. That song, “The Lord God Bird,” was inspired by an ivory-billed woodpecker rediscovered there. Then, in October 2005, The Guardian reported that Oregon was a “likely contender” for Stevens’s next state. Stevens had spent several summers there as a child, visiting his mother and stepfather. “The state has so far inspired some very simple guitar-based songs from Stevens,” the reporter, Laura Barton, noted.

But the Oregon album never materialized—not unless you count Carrie & Lowell, Stevens’s grief-borne 2015 album, which is thick with references to the Beaver State. (“It is essentially his Oregon album,” Gill says.) Nor did we ever get a Rhode Island 7-inch, as Stevens mused about releasing in that same Guardian profile (“Not all of the 50 states will be awarded a full-length album,” Barton wrote). Instead, he released another album about … Illinois. The 2005 album had yielded such an overflow of material that Stevens released an album of outtakes a year later, called The Avalanche. Here we got tunes about Saul Bellow and Adlai Stevenson and three different renditions of “Chicago.”

In the press release for The Avalanche, Gill wrote: “Sufjan has still not made an official decision on the next state he’ll tackle in his epic 50 States project, but we will definitely keep you posted.” Privately, though, Stevens seemed to be growing bored with the project. At some point—nobody knows when—he abandoned it. Though his next project, The BQE (2009), was also rooted in an exploration of place, he would never release another album about a state.

Meanwhile, fans saw signs everywhere. Calvin, the fan from Iowa, remembers hearing around 2007 that a relative had served Stevens at a local Jimmy John’s sandwich shop. “That kind of fueled our imaginations,” Calvin says, “like, what if he’s going around Iowa getting material or working on an Iowa record?”

By 2009, the faithful were growing impatient. Early that year, Paste editor Josh Jackson practically begged Stevens for another state entry: “Chinese Democracy miraculously saw the light of day last year,” he wrote. “Would it be too much to hope that 2009 is the year of Oregon? Or New Jersey?” Nine months later, Stevens publicly admitted the whole project had been a “promotional gimmick.” This concession was largely buried in a Guardian interview about the BQE project. Many fans never saw it. But the singer’s next proper album, The Age of Adz, was a jarring enough stylistic departure that it was clear he had moved on. (By this point, he had also moved on from Gill, having hired a new publicity team.)

And yet the 50 states project continues to exert a patriotic pull over the indie-rock imagination. Maybe it’s a nostalgic signifier of indie folk’s early-aughts golden period, or an unfulfilled promise, or just a nice fantasy to believe that 48 albums as great as Illinois are lurking just around the corner. Even as Stevens has graduated to Oscar nominations and Pride Month songs, some fans still carry the flag for his unfinished geography project. As the comedian Avery Edison tweeted in 2015, “Don’t keep asking where Frank Ocean’s album is if you’re not doing the same for the 48 U.S.-themed ones we’re owed by Sufjan Stevens.”

The following year, after Donald Trump’s election, an Illinois writer named Nicky Martin called on Stevens to finish the project as a matter of national urgency. “Once Sufjan releases a record for every state, we’ll understand ourselves better as Americans,” Martin wrote in a hilarious and bizarre Medium post. “When we understand our American heritage, we’ll stop voting against our own interests!”

Is there any chance Stevens might eventually resume the project? “I don’t think there’s any way he would consider doing another state release,” says Gill (who, it should be stressed, is not speaking on the artist’s behalf in any capacity). “But you never say never with Sufjan. He already has two box sets of Christmas songs—that’s crazy.”

Zach Schonfeld is a freelance journalist and writer based in New York. He was formerly a senior writer at Newsweek.