In “The Battle of Starcourt,” the climactic eighth chapter of Stranger Things Season 3, the heroes of Hawkins confront their fears, settle their differences, and battle monsters above and below ground. On the surface, the kids—led by Eleven, who’s lost her powers—fend off a giant, gooey monster made by the Mind Flayer, while far beneath the mall, the adults infiltrate a supposedly impregnable secret Soviet base to destroy the machine that’s reopening the portal to the Upside Down.

The only person with a more difficult assignment than that two-front fight was the man in charge of making both the monster and the machine: Paul Graff, the series’ senior visual effects supervisor.

“Chapter Eight … was like an impossibility,” Graff says. “Like literally an impossibility.”

As its largely teenage cast has grown physically and emotionally, Stranger Things has adjusted by tackling more mature themes. The resulting richer, darker narrative coincides with more complex special effects, which means that to a greater degree than before, CGI played a starring role. Season 2’s nine episodes required about 2,000 visual effects shots. Season 3’s eight episodes upped the ante, calling for about 2,500 visual effects shots on a similar, approximately 18-month production timeline. “Generally speaking, the difficulty level in Season 3 is a little higher than it was in Season 2,” Graff says.

Season 1’s main antagonist was a single Demogorgon, a monster small enough to be played by a person in a suit. Season 2 introduced a pack of adolescent Demodogs and the ethereal, smoky Mind Flayer, a foe confined to the Upside Down that’s mostly glimpsed from a distance. In delivering an even more dangerous adversary, Season 3 doubles down on the body horror, featuring exploding rats, liquefying humans, and the abomination assembled from their sentient organic material: a 22-foot-tall, “dinosaur-sized” monster.

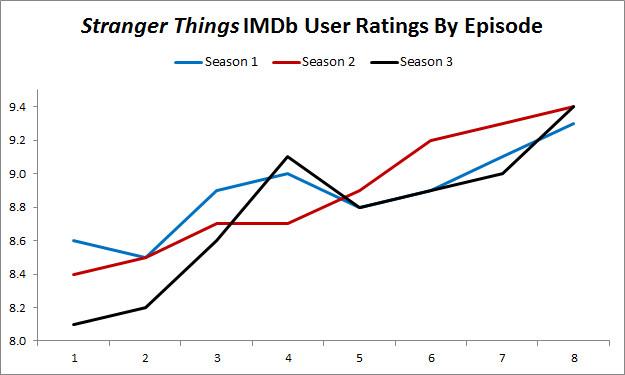

If we graph the series’ IMDb user ratings—excluding Season 2’s extremely low-rated seventh chapter, “The Lost Sister,” which took place outside of Hawkins and bypassed most of the main cast—we see that viewers tend to enjoy episodes progressively more as each season proceeds.

Those ratings reflect the story structure employed by the Duffer brothers, who engineer each arc to operate as a crescendo. Graff compares that trajectory to Hopper’s 8,000-calorie kitchen concoction from Season 2. “Stranger Things is a triple-decker or an octuple-decker Eggo,” Graff says. “That means every chapter escalates over the previous chapter. … And there’s something really scary about that, because you feel like you’re underwater already in the first chapter, and then you get into the second chapter.”

“Scary” also describes Graff’s workload, which grows heavier as the evil festers and the action intensifies. In Season 2, Graff’s team was tasked with designing the five-stage life cycle of a Demogorgon, starting with baby Dart. Season 3 also depicted the growth of a nightmarish monster, this time showing how the remnants of the Mind Flayer expelled from Will in Season 2 gradually mold a physical vessel that resembles the Mind Flayer’s form in the Upside Down.

The visual effects team started by sketching out the massive mall monster, which initially lacked teeth. As with Season 2’s tadpole-esque Dart and larger “Frogogorgon” and “Catogorgon,” the goal for the intermediate stages was to hint at but not completely telegraph what the mature monster would look like as it morphs from rat-size, crawling creature in Doris Driscoll’s basement to the “Tom/Bruce monster” in the hospital scene to the final, towering terror. “It’s like the Mind Flayer incarnating itself into a body,” Graff says, adding, “We had to figure out what does that look like, and then how do we get there from exploding rats.”

In standard Stranger Things fashion, Graff was told to model the monster after an ’80s cinematic touchstone. “The very first meeting that we had with the Duffers was that Season 3 was going to be like The Thing,” Graff says. “John Carpenter’s The Thing was what they wanted to explore, and that means we now have fleshy, goopy, liquid, heavy monsters … a hybrid between a creature and an effects simulation of traveling goop.”

Released in 1982, The Thing was a triumph of practical, or non-computer-generated, effects. The Duffers prefer to use practical effects wherever possible, but the mobile monsters they’ve conceived are often impossible to portray with props, costumes, or models. In the visually more modest Season 1, they aimed for an 80-20 split between practical and CG effects but ended up closer to 50-50. Season 3 is all CG, with no practical component to any manifestation of the monster. “It is all aiming to have a resemblance to practical effects, but it’s not practical,” Graff says, confirming, “There was no practical goop ever.” Not only were no real rats harmed in the making of Season 3, no physical fake rats were, either.

The monster’s most memorable embodiment is its midsize, fluid form, a shape-shifting mass of decomposing parts and digestive juices congealed into a skittering, spiderlike terror—“chunks of meat,” Graff says, with “a coat of goo.” Given the aesthetics of The Thing, Graff says, “It had to be really wet and shiny and drippy.” Mission accomplished, courtesy of visual effects company Rodeo FX, which won the contract to create the goo. Graff continues, “Basically, it’s body parts. The secret there is to not be too repetitive. We didn’t want it to feel like it’s only made out of one substance or it’s really self-similar, but rather has a nice mix of components with different viscosity and detail, because this is literally made out of anything, and have some bones swim around in it and such. It’s a little bit like painting with pieces of corpses.”

Lethal as it is, the “Tom/Bruce monster” is still a work in progress. “I wanted to play with an asymmetrical design,” Graff says, citing the “Frankensteiny and Hunchback of Notre Dame, limping design of the creature that’s not 100 percent perfectly executed. It’s good if it feels like there’s a designing force behind it, but there’s also a lot of chaos and a lot of imperfections. It’s just trying to get there as fast as it can. So for me it was really cool to have this monster with one big leg on the right side and a lot of smaller legs on the left side, and it’s just limping and pounding and stepping hard as it propels itself forward.”

When the Tom/Bruce monster flees from the hospital and oozes into the sewer, it leaves a leg behind. “That’s the Duffers,” Graff says. “They wanted to see it have a bone left behind. We were thinking, like, ‘It has bones, so what happens with the bones when it goes through a small orifice? It’s going to leave some of those behind.’”

Some Stranger Things viewers have argued that the queasy-making monster scenes stray too far into gross-out territory. (My wife, who watched some of the season through splayed fingers and only listened to the squelchiest scenes, would agree.) According to Graff, though, the visual effects crew actually spent more time dialing down the grossness than it did ramping it up.

“There’s a fine line that has to be traveled between being gross and cool,” he says. “We wanted to make something that never looks shocking in the sense of it hurts, and you feel like this is a cruel situation. It’s always a little bit of an absurdity meter woven into these shots, and we felt that we want to be really gross and splatty, but we don’t want to cause any harm with anybody, and I hope that we found the right balance.”

The actors, of course, couldn’t see any of the yet-to-be-rendered horrors hunting their characters. Graff says Season 2 taught him the importance of providing something interactive and real to react to, so the crew used some sort of stand-in for most major effects. Graff’s staff bought a box full of “all kinds of rat dolls” and remote-controlled rats, but when the latter proved insufficiently steerable, they switched to silver balls, which reveal the lighting in each shot and make it easier to shade the computer-created animal. The balls rested on small sacks of sand attached to strings that could be tugged to simulate movement of the rats.

The stand-in for the Tom/Bruce monster was a stuntman in a red, form-fitting suit and a two-foot-diameter, chrome-ball helmet. “I was working this guy for weeks to make sure he [did] not get intimidated by being in a ridiculous outfit and screaming at the top of his lungs to create a reaction,” Graff says. The sight of a scampering stuntman in spandex is arguably more unsettling than the monster itself.

For the monster’s most evolved form, the special-effects workshop built a black, “blimp-sized” mock-up of its head that could be mounted on a pole. But the head was too heavy to operate—roughly 50 pounds—so the team opted instead for a three-foot-diameter beach ball. One of the animators who had worked on the monster played puppeteer and moved the beach ball around.

The notorious rats and the monster may overshadow a whole host of other technically complex effects from the season, including the melting faces of the Flayed (inspired by Raiders of the Lost Ark) and the futuristic Russian machine, which Graff says the Duffers envisioned as “a mix between a ray gun and a turbine, like a jet engine.” Other CGI was so subtle that most viewers weren’t aware of what it was; Graff estimates that only half of the season’s visual effects shots could be identified as such.

On a narrative level, Season 3 left us with a lot of lingering questions. We still don’t know precisely what the Mind Flayer is, why it wants to “end everyone,” or what the Russians hope to accomplish by unleashing it on Indiana. But at least we now know how the digital monster was made.

For Graff, the process of creating unholy virtual life for the Duffers is fulfilling but frantic. “The most valuable resource of Stranger Things is Duffer time,” he says. “These guys are working 24/7, 12 months a year. They never stop.” Even so, the scripts arrive on a schedule that necessitates tight turnarounds. “These chapters sometimes come in weeks before we start shooting them, and the later chapters come in later and they are bigger. It’s like this complete insanity that starts developing, and you’re asking yourself, ‘How are we going to do this? How the hell are we going to pull this off?’”

They didn’t do it by expanding; Graff says the size of his staff stayed the same between seasons, although he notes that “we did get a trailer this time.” The secret, he says, is setting and meeting short-term targets, avoiding dead ends, and fostering close collaboration. “It’s a little bit like the AV club,” Graff says. “The teenage AV club plays a central role in Stranger Things. It is actually us, the Duffers, and everybody involved in the show. It’s like a bunch of kids that want to play, especially the Duffers. They could do whatever they want to do. They love Stranger Things because they get to play, and they’re in it to basically expand the envelope always.”

Consequently, Stranger Things’ still-unannounced Season 4, which will expand beyond Hawkins, will likely test the series’ monster-maker in ways that even the apparent “impossibility” of Season 3 did not. The already elevated visual effects count, Graff predicts, can only increase. “I have a feeling that’s going to be the case for sure.”