It all came down to the white man with the giant Afro. Kyle Troup lifted a hand to get the crowd juiced, then closed his eyes. He picked up his multicolored Storm bowling ball from the ball return. “It’s my time,” he said. “It’s my time.” Facing a single roll that could win or lose the match, Troup felt excited, like an Olympic athlete in the clutch. Telling the story later, he pointed at his forearm and said, “I get chill marks just thinking about it!”

If everything you know about bowling comes from The Big Lebowski or your 10th birthday party, Troup is exactly what you want a pro bowler to be. Last Wednesday, Troup paired his planetary Afro with a green shirt and dark green plaid pants, which made him look like an old tin of Christmas cookies. After one orgasmic strike, he pulled an Afro pick out of his pocket, autographed it, and handed it to a young woman standing in the front row. Troup is a second-generation bowler who followed his dad to the PBA tour. His dad’s name is Guppy.

The Elias Cup in Portland, Maine, straddled the line between mesmerizing skill and camp. For the team event, bowlers were split into two sides. The bowlers on Troup’s Portland Lumberjacks team had nicknames like Hitman, Shark, and Big Nasty. Their opponents had nicknames like T.J., The Real Deal, and Beef Stu.

This mise-en-scène is so attractive to hypothetical Midwestern diner-goers that Pete Buttigieg has made bowling a campaign prop. But what works in Iowa and New Hampshire can be deadly elsewhere. For two decades, the decline of bowling leagues has been a sociologist’s shorthand for the crack-up of American civic society. GoBowling.com’s tagline—“the original social network”—sounds a little like a person deciding late in life to be extremely online.

But two things changed, putting bowlers like Troup in a different light. Viewers watching his climactic roll on FS1 saw more than the old shot of the ball traveling up the lane. Fox put a red tracer on the ball, like they do tee shots at the U.S. Open. So viewers followed Troup’s ball as it started right, flirted with the gutter, and then broke at the sixth board before making its journey to the “pocket” between the 1 and 3 pins. Viewers knew Troup’s ball reached a speed of 19.4 miles per hour (very fast) and moved at a rate of 504 revolutions per minute (very powerful). All the data gave an analytics-friendly spin to Troup’s proclamation that “I just dead-laced it.”

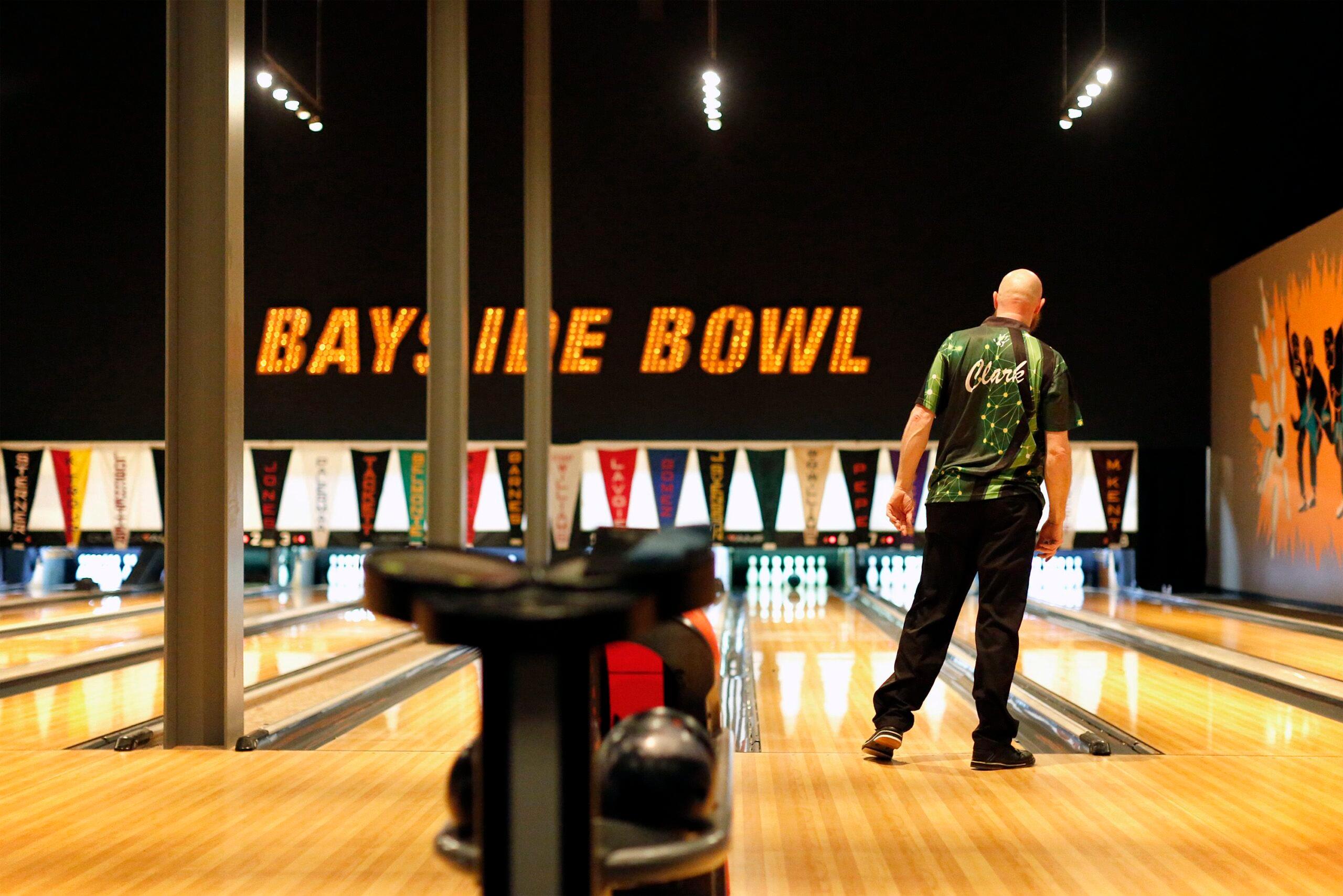

The crowd in Portland wasn’t a church-pews bowling crowd. Bayside Bowl was filled with beer-swigging late-30-to-early-40-somethings who think of Lebowski as a sacred text. They didn’t care about bowling decorum. As Troup held his ball, they chanted, “The Troup, the Troup, the Troup is on fire!” One Portland regular, whose league name is White Russian, was wearing a Santa outfit. On Thursday, she showed up at Bayside in full Maude Lebowski Viking regalia. Her friends wore bowling pins on their heads.

It has become this comfort food of sports. You watch it. You’re happy. You’re placated. You’re not taken too high or too low.Rob Stone, play-by-play announcer

Fox, White Russian, and Troup’s Afro are part of a grand experiment. Bowling might never recover the 9.0 ratings it pulled down on ABC in the three-network era. But it might become a cable innings eater, like ESPN’s poker tour was 15 years ago, with its own collection of stars. What Fox wants is for a member of the Lebowski generation to stumble across bowling and say, “Oh, yeah, that’s the guy with the hair.”

Holding his ball, Troup stared straight ahead. He rolled. He got nine, the exact score the Lumberjacks needed to win. When athletes celebrate, they tend to grab the guy who won the game by both sides of his head and scream. The Lumberjacks’ manager took a few steps toward Troup, grabbed both sides of his Afro, and shook it in giddy celebration.

Bowling has been on television for 57 consecutive years. Its announcers have included ABC’s amiable Chris Schenkel, Mel Allen, and even ex-Dodger Leo Durocher. Before the age of HDTV, bowling had an advantage over big sports: Where those looked like a mess of dots on the screen, a bowler’s ecstasy and agony could be savored. Today, Fox shows the same replay for a Troup miss—a super-slow-mo shot of his face slowly turning downward—as it does for an Aaron Rodgers interception.

Last year, as the PBA was winding up its contract with ESPN, a certain malaise settled over the tour. “It was just going through the motions and then waiting to see when this thing was going to fail,” said Randy Pedersen, a Fox analyst and Hall of Fame bowler. “How long was it going to be before this thing just takes a big, giant deuce and then what do we do?”

Last spring, when Fox acquired the rights, it gave bowling the same embrace it once gave neglected sports like hockey. “They needed to be held, they needed to have their head petted and told they’re beautiful and shiny,” said Rob Stone, Fox’s bowling play-by-play announcer. On December 23, Fox aired the PBA Clash after an NFL single-header and drew an audience of 1.8 million viewers. The next month, Joe Buck plugged the PBA during a playoff game. “I wasn’t even sure Joe Buck knew what bowling was,” the English bowler Stuart Williams told me.

Because it gets little coverage in newspapers or on SportsCenter, bowling tournaments are evergreen. Fox can replay them 10 times, just as ESPN once did poker. “That is how you become a household name if you’re a pro bowler,” said Norm Duke, who won twice on tour this year. “You want to be on television every dadgum day. You want to be like a soap opera.”

“It has become this comfort food of sports,” said Stone. “You watch it. You’re happy. You’re placated. You’re not taken too high or too low.”

Back in the ’60s, Schenkel lent bowling an NFL-style gravitas. Stone comes from a different school of play-by-play. Stone calls bowling like he’s working alongside Jason Bateman in DodgeBall. After a bowler named Anthony Simonsen rolled a nine-count in one frame of this year’s playoffs, Stone said, “Stupid 10 pin left standing. Worst pin in the business!” Later, he said: “Seriously, 10 pin, what is your problem today? … The 10 pin is my enemy.”

If Kyle Troup is like a fantasy of a bowler, Stone is a fantasy of a bowling announcer. He is part super-fan, part purring psychologist: “That’s how you do it, Sean. … Keep it cool, Billy. Keep it cool, kid. … That was so smooth, so clean. … Hambone, yeah!”

This spring, when Bill “The Real Deal” O’Neill rolled six straight strikes to start a match, Stone and Pedersen had this exchange:

Stone: “Hey, Randy. You thirsty?”

Pedersen: “I am.”

Stone: “Crack open that six pack!”

Tom Clark, the PBA commissioner, said he gets angry letters about Stone from traditionalists, and some of them appear to have been composed on typewriters. “When I was competing, it was a lot drier,” Pedersen said of the commentary. “They tried to make it a golf thing. We realized it’s just not that animal. This is an entertainment.”

More replays and lustier announcing gave the PBA tour a nice spiffing-up. But as television, bowling had a fundamental problem. It looked too easy. “That’s kind of where our sport failed in the last 20 or 30 years … really getting across what makes it so difficult and why we’re so good,” Troup said. The Lumberjacks won the first game of the Elias Cup semifinal with a score of 226. A lot of league bowlers might think, “I can do that when I’m drunk.”

Fox wanted viewers to appreciate a bowler’s skill by showing just what they’re up against. For instance, the lanes at local bowling alleys are oiled in such a way as to help you get a high score. At PBA events, they’re oiled to challenge a bowler and test their skill. “Bowling professionally is really akin to what a golfer faces on a green,” said Zac Fields, Fox’s senior vice president of graphic technology and integration. The PBA started using blue oil so a TV viewer can appreciate, say, a 42-foot Mark Roth pattern.

Since bowling is the rare TV sport that plays vertically rather than horizontally, Fox made StrikeTrack a permanent fixture on the right side of the screen. In real time, a viewer can see precisely where a ball travels across the lane, and see how a deviation of even an inch can change the result. “Until you have a visual representation of that,” Jason Belmonte, an 11-time major winner who’s often called bowling’s Tiger Woods, said, “it becomes almost impossible for someone who doesn’t understand it to learn it.”

Not only does my opponent have to try and beat me, they also have to try and beat Bayside Bowl. I feel like they’re on my side.Kyle Troup

There’s a fine line between dressing up bowling with analytics and pissing off its diehards. Geordie Wimmer, Fox’s executive producer of bowling, told me: “Fox has had issues in the past, whether it be with the glowing puck in the NHL or our soccer coverage, where we talk down to fans. That’s the criticism. I always see it as us trying to bring a sport up and make it better for everybody.” A plan to put cameras in pins was shelved because Fox couldn’t figure out how to make sure the camera would face forward every time the pins were racked. Fox wanted to simplify bowling’s complex scoring by starting with 300, a perfect game, and then showing how a bowler’s maximum score declined frame by frame. Maximum score is still used in the broadcast, but alongside traditional scoring.

Just as win percentages and revealed hole cards turned poker players into geniuses or idiots, bowlers are now more answerable to the fans. “Not only are you accountable for your good shots,” said Belmonte. “You’re accountable for your bad ones.”

Troup, speaking in the voice of a newly wised-up TV viewer, told me: “Oh, that’s why I can bowl 220 drinking my beer and eating my chicken wings and this guy won $500,000 bowling 195.” Fox is trying to make a game seem more like a sport.

Last Thursday, I found Charlie Mitchell on the roof of Bayside Bowl. He was wearing a plaid sports coat that matched Kyle Troup’s pants. Mitchell is an intriguing figure in the bowling universe: an outsider who, in the process of trying to score his next drink, managed to modernize the sport.

Mitchell worked for the ACLU in Washington, D.C., until 2007. He moved to Portland and started a bowling league to pass the time during Maine’s winter nights. “It was an excuse to go drinking on a Tuesday is all it was,” he said. Mitchell gave himself the nom de bowling of Karl Hungus, Lebowski’s “nihilist” character. He and the hundreds of pals who’d joined the league knew nothing about bowling. But they knew how to run up a bar tab. Erika Puschock—a.k.a. White Russian—told me: “We are a drinking league with a bowling problem.”

In 2010, when Mitchell’s league outgrew a local alley, he and a partner built their own bowling palace northwest of downtown. Bayside Bowl offers some of the same hipster bait as “boutique” alleys across America. There’s an Airstream trailer on the roof where a latter-day Walter Sobchak can order jackfruit tacos, and a summer movie series that showed the documentary Helvetica last month. But beyond the aimless hipsters, Bayside cultivated a fiercely loyal army of regulars who’ve decided bowling isn’t just for grandpa. These are just the fans Fox and PBA wanted.

When the PBA held its first tour event at Bayside, in 2015, Mitchell’s regulars started tailgating in the parking lot at 6:00 a.m. (A few passed out by 7:30.) Later, they would crowd into Fox TV shots, dressed like beauty queens or Champ Kind from Anchorman. It was like the missing link between The Rocky Horror Picture Show and College GameDay. “Everybody thought this was fake, that the PBA had set this up and these were paid actors,” Mitchell said.

“If you rewatch the first season here,” Mitchell said, “Pete Weber approaches the lane on a spare shot, then smiles and steps back. That’s because one of our people fell into the lane.” That day, Mitchell made a rule for PBA events: If you’re too drunk to appear on television, you have to sit in the bar.

Bayside has none of the expectant silence of hallowed alleys like Fairlawn, Ohio’s Riviera Lanes. “We want this place to be the Cameron Indoor Stadium of the PBA,” Tom Clark said. Last week, a DJ played “Seven Nation Army” and “Sweet Child O’ Mine” while the matches were in progress. Baysiders cheered before, during, and after the bowlers rolled. “At Bayside, just picking the ball up off the ball return is a big enough moment for them to go crazy,” Belmonte said.

The Elias Cup finals were held on lanes on the east side of the building, which is pleasantly claustrophobic, like the lanes at a church rec center. Kimberly Pressler, Fox’s lane-side reporter, had to wear two earpieces so she could hear her cues.

Baysiders had a chant for everything. As a bowler tried to pick up a spare, they yelled, “Clean your plate! Clean your plate!” When a bowler asked for the pins be re-racked—bowling’s equivalent of a time out, sometimes deployed strategically—they yelled, “Re-rack! Re-rack!”

The crowd greeted every bowler with a signature cheer. For BJ Moore (with evident relish): “More BJ! More BJ!” For Dick Allen (ditto): “Diiiiick!” At Thursday night’s final, the bowler Anthony Lavery-Spahr was greeted with the chant, “Iiiiice Bucket!” Even Clark, the PBA commissioner, had to find a Baysider to explain the reference. It turns out that Lavery-Spahr’s initials are ALS, and there was that ice bucket challenge five years ago … and that’s Bayside humor for you.

At first, some bowlers regarded Bayside’s wall of sound as either baffling or distracting. “The greatest players in the world were missing easy spares that they make 95 percent of the time,” Clark said. But for a brand-builder like Troup, these were his social media followers made flesh. “Not only does my opponent have to try and beat me, they also have to try and beat Bayside Bowl,” Troup said. “I feel like they’re on my side.”

I found Troup relaxing on the same roof deck before his match. Against the setting sun, his Afro took on the character of a celestial body, and for a moment it was like I was staring at Tatooine’s twin suns.

Inside Fox, there have been conversations about how to bring out bowlers’ personalities. One idea is to play up the rivalry between fan favorites like Troup (“I’m on the hero side of the PBA”) and players like Belmonte whose two-handed style has earned him his share of detractors. Bowlers resist going too far down the road to WWE. “The day that someone from Fox tells me to start saying certain things is the day I’m probably very, very quiet,” Belmonte said. “Because I don’t want to conform to someone else’s plan for me.”

Bowling doesn’t need much world-building. Bowlers have their own world that’s just perfect. They have bowling clichés. (“I’m just a guy trying to knock down 10 pins.”) They have hidden desires. (Kris Prather, who won this year’s PBA playoffs, told me that if he hadn’t become a bowler he would have been a marine biologist.) Bowlers stow their bags under tables in the alley while they compete, and work on their balls in plain sight. Before a match, you might find one playing Golden Tee in the alley’s arcade. When you interview a bowler, they often give you their cell number and tell you to call if you need anything else.

If you want gamesmanship, bowling has it. In the Elias Cup finals, Belmonte, who was bowling for a team called the LA X, held his pose near the foul line as he bowled a strike. In bowling, this is called “posting.” It indicates good form and intense concentration. The next bowler after Belmonte was Ryan Ciminelli, who was bowling for the Lumberjacks. Ciminelli threw a strike, too, held his form even longer than Belmonte, and turned his head to peek back at the other players. You know, just to send a message. It was one of the most badass things I’ve ever seen.

Bowlers are proletariat heroes. On tour, four bowlers might crowd into a hotel room to save money. This year, the tour produced just one six-figure winner’s check, for $100,000. “I was nervous on my wedding day, but this tops all of it,” Prather said as he contemplated it. Before that, Prather’s career winnings for five years on tour came out to around $180,000.

Bowling’s greatest advantage is its own aesthetic, which no network could monkey with even if it wanted to. In Portland, I met 25-year-old Jakob Butturff, from Las Vegas, an amazing lefty who’s no. 2 on this year’s money list. Butturff’s calling card is the giant Cubic Zirconia studs he wears in his ears. I told Butturff I couldn’t imagine someone with his name being an All-American quarterback. It just didn’t fit. Butturff is the perfect bowler’s name.

“Definitely,” Butturff said.

Though they’re targeting the Lebowski generation, a lot of bowlers aren’t huge fans of Lebowski. Some haven’t even seen it. “I get a lot of shit for that,” Troup said.

“The reason why I haven’t watched Big Lebowski,” Prather explained, “is because it’s not about bowling. It just has bowling in it.” Stuart Williams told me he’s not high on Lebowski because he doesn’t get stoned. All three said their go-to bowling movie is Kingpin.

The fact that bowlers prefer Kingpin is telling. It’s a reminder they think there’s something intrinsically cool about the sport that doesn’t need the validation of the Coens, much less the Murdochs. It’s also a polite form of hauteur that elevates the pro bowler over every other dude (or Dude) who hangs around an alley. As Randy Quaid says in Kingpin, “Wow, it’s kind of intimidating to be in the presence of so many great athletes.”

The final night at Bayside was the most endearing. When Troup’s Portland Lumberjacks won the Elias Cup, the Bayside regulars ran from the stands into the lanes and mobbed them. Tom Clark, the PBA commissioner, thought it was the first lane-rushing in the history of bowling.

I ran into the lane and joined the celebration. As Troup’s Afro bobbed up and down over everyone’s heads, I felt a genuine, unmanufactured joy. Champagne was poured into the winners’ trophy. Troup took a big swig. “I got one question,” he said. “Who’s ready to party?!”