In Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino’s 2007 film, a question gets asked from the bar of the Texas Chili Parlor. With platinum blond hair falling past her shoulders and a margarita in a glass boot in front of her, Pam (as played by Rose McGowan) asks, “How exactly does one become a stuntman, Stuntman Mike?”

Wearing a silver satin jacket adorned with Icy Hot patches, Stuntman Mike (as played by Kurt Russell) replies, “Well, in Hollywood, anybody fool enough to throw himself down a flight of stairs can usually find somebody to pay him for it.”

Stuntman Mike eventually reveals he actually got into the business through his brother, Stuntman Bob, but that self-deprecating boast about toughness captures what Tarantino adores about old-school stuntmen.

Mike is the villain of Death Proof, but 12 years later, Tarantino’s brought back the archetype for Cliff Booth, Brad Pitt’s character in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood. Tarantino presents Booth as the rugged hero of the film. Even if he possibly killed his wife.

Booth is the quietly charming, unflappable force who’s willing to take a punch, fall off a roof, or get hit by a car for Leonardo DiCaprio’s insecure, often buffoonish actor Rick Dalton. And if the opportunities for Booth to get paid by putting his body in harm’s way have disappeared, he’ll happily just get drunk with Dalton or fix the TV antenna on his roof. But in order to help inform the audience about what a badass Booth is, Tarantino turned to the film’s stunt coordinator—Zoë Bell, a 40-year-old New Zealand native who’s been collaborating with the writer and director for more than a decade.

Eruptions of violence have always been present in Tarantino’s films, but he didn’t get into heavy stunt work until the Kill Bill movies. Bell, who previously worked with Lucy Lawless on Xena: Warrior Princess, doubled for Uma Thurman during the movie’s vicious and acrobatic fight sequences. (Last year when Thurman revealed to The New York Times that she was injured in a car accident during the making of Kill Bill: Vol. 2, the film’s stunt coordinator, Keith Adams, told The Hollywood Reporter that he wasn’t on set that day and hadn’t been notified that Thurman would be driving the car herself.)

At times Tarantino’s follow-up, Death Proof, feels like he made it explicitly to showcase Bell, who plays a version of herself in the film. In one scene where Tarantino references his own opening scene for Reservoir Dogs, rotating the camera around a restaurant’s table in a single shot, the characters aren’t talking about Madonna and dicks, but about how incredible Bell is. “Physically speaking, Zoë is amazing. I mean agility and reflexes, nimbleness, there are few human beings who can fuck with Zoë,” says Tracie Thoms’s Kim. Bell proves just what she is capable of later as she hangs from the hood of a 1970 Dodge Challenger during one of the greatest cinematic car chases of this century.

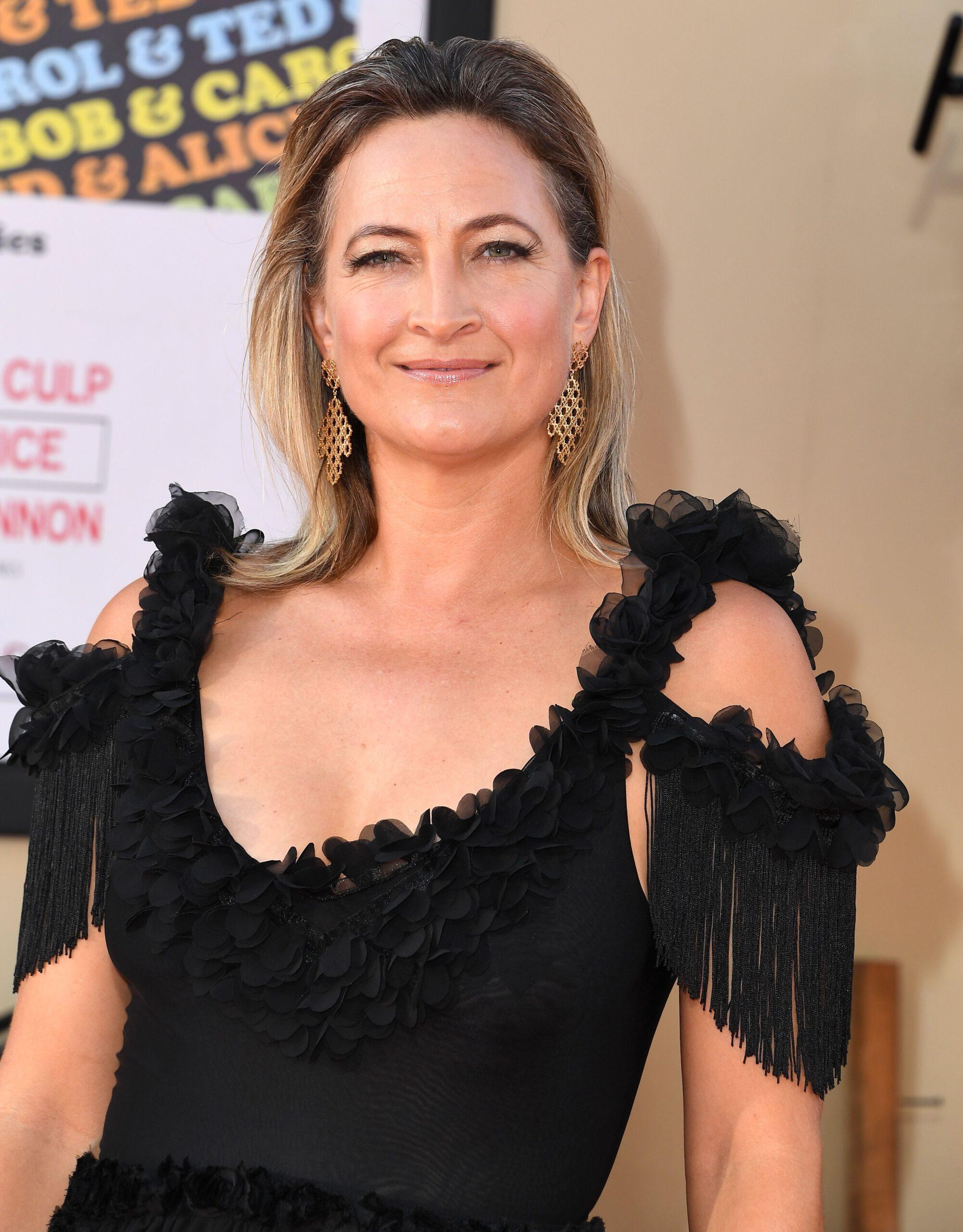

Under stunt coordinator Jeffrey Dashnaw, Bell continued to appear in and/or work on Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, and The Hateful Eight. She also started getting more into acting and began to explore producing and directing. Her highest profile stunt work in years came in 2017 as she doubled Cate Blanchett as Hela in Thor: Ragnarok. Then Tarantino asked her to be the stunt coordinator on Once Upon a Time ... (She also briefly shows up as Janet, the wife of Kurt Russell’s fictional TV stunt coordinator, Randy, and the character who calls out Cliff’s rumored homicidal past.) While most stunt work now relies on digital effects, Tarantino tasked her with making the stunts as era-appropriate to the 1960s as possible. That meant, for one, a lot more pads and a lot fewer wires. I spoke with Bell about the role that stunts (and stunt performers) play in Tarantino’s films and why Brad Pitt taking off his shirt on that roof wasn’t just a beefcake shot.

Why did you decide to transition back into stunt work?

I don’t perceive this as a transition back into stunt work. I perceive it as—I guess this sounds a little bit existential—making career choices that double as life choices. So there’s Thor—Taika [Waititi], the director, is a friend of mine; [stunt coordinator] Ben Cooke, he’s my stunt brother from way back. I was going to be working closely with Cate Blanchett; I was going to be close to New Zealand; it was a regular paycheck, which sometimes in the acting game hasn’t been quite as regular. There’s a bunch of things that went into it that I was like, I really want this as the life that I’m living.

Then when Quentin comes along and offers me this epically moving, romantic, full-circle notion of being the stunt coordinator on a movie called Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood about an actor and a stunt guy, it’s a massive responsibility and a huge honor, and one of those life stories.

When you were discussing the stunt work that he wanted in this film, what type of direction did he give you?

The most relaxed, natural part of the process for me was the creative stuff, because I’ve been back-and-forthing with Quentin in that manner for 10 years in various roles. A lot of that was watching period pieces, looking at the reference list that he had running, absorbing as much of that, and then really, at the end of the day, just listening and letting Quentin paint pictures in my head, which is not hard.

In terms of painting pictures in your head, just as an example, there’s the scene where Cliff does this series of quick jumps to get up to Rick’s roof. Does Quentin say, “I see him doing three jumps”? Or is he more general like, “We need to find a cool way to get him up to the roof”?

It depends. Some particular scenes that are drama-based or have either literal dialogue or physical dialogue, he’ll stand up and act it out. He kind of becomes each character and you become immersed in his imagination. For things like the jumping up on the roof, he’s like, “Zoë, I want something that’s easy for a stuntman, but everyone else would go, ‘What?! How?!’ He’s going to climb a chimney, or he jumps up something, or he pole vaults, or he flips up and over.” So he’s got an idea of it, but then he wants me to throw suggestions that would fit to the location, the scene, what happened before, what happens afterward, and then he’ll know it when he sees it.

It’s interesting with Cliff’s character, because at the start of the film he admits he’s not even really a stuntman anymore, but we have to see what he’s capable of physically because of what he does later in the film. There’s got to be character development through the stunts he does in his everyday life.

We as stunt people know that some of the most beat-up looking women and men in their 50s were probably some of the baddest asses, even if they’re maybe moving a little slower. A big part of it for us was just that [Cliff] was a very talented stuntman whose loyalties maybe cost him an amazing career because he was loyal to Rick, whose career didn’t take off the way Rick was hoping. It also tells you a lot about what Cliff’s priorities in life are.

There are these layers that are so fun to peel back that speak to the fact that before getting paid to do the glossy version of action, [Cliff’s] a war vet. He’s actually been through some legitimately horrific stuff. And at the end of the day, rolling around on the movie set, drinking a carton of milk and smoking cigarettes is a dream compared to where he’d been. So I love those little glimmers of when you get to see “Holy shit, this dude is so capable.” He’s not just some stoner dude living in a trailer with his dog. Well, maybe he is, but he’s also, you know, a multidimensional character.

You only learn he’s a war vet through a single line of Rick’s dialogue, halfway through the movie, and then it’s never mentioned again. Did you guys have more in-depth discussions exploring that history?

We definitely explored it with Quentin and with Brad. It became an important thing for Cliff’s stunts. There was talks of “Do we show when he takes his top off that he’s scarred up?” The map of his life we see on his body. Then there’s the way that he stands and faces the world. Green Beret was the keystone for Quentin—[Booth] was a badass and he’d killed people and had to witness horrific things.

Obviously Quentin has respect for all sorts of people in the movie industry, but looking at his filmography and his interests, do you feel like he has a special affinity for stunt performers?

I feel like he does. I don’t mean to be putting words in his mouth, and maybe I’m projecting because I feel this way, but there’s something about stunts to this day that still carries a little bit of that old school. You still got to be a little rough and tumble. Stunts have definitely been gentrified, but you can’t be a stunt person and be worried about getting hurt. You need to be savvy about how to stay safe, but you can’t be doing it worried if you’re going to be getting a bruise or a scratch. I think that that lack of preciousness is probably one of the things that appeals to Quentin, the Wild West of it.

Nowadays so much stunt work revolves around things like wires and CGI. How do you make a movie that features old-school stunt work but is still compelling to modern audiences?

Some of the stuff we wanted to look stylistically authentic to the time— because it is [Rick Dalton’s fictional TV show] Bounty Law—or we are reenacting something. Because as audience members we’re far more savvy and educated now—you don’t want it to just look hokey unless you’re playing on the hoke. There was one sequence that ended up not making the film, but it was very much a haymaker-type fight and a bar brawl—flying over the tables and crashing over the bar. We still wanted the connections to look solid and we still wanted it to look painful, but we were playing into the heightened sort of slapstick of that time in that particular sequence.

In one of the opening sequences [for Bounty Law] there is a balcony fall. Rick Dalton shoots him, he falls off the roof, he smashes through the balcony and he hits the bottom floor. That’s straight out of old-school westerns. I had done a bunch of research about it and people got pretty drilled doing free falls like that. When it came time to do that I took it upon myself to believe that the authenticity of a gag like that is an important piece of the movie. Whether you notice it or not, it had to be done as authentically to the old school as possible. It took weeks of prep and finding the right person. These days you’ve got so much technology and there’s so many techniques and tools and devices that we have that keep everyone safer. When you do something like a balcony fall, we have wires and we have CGI at our disposal. To consider not using those things, we have a responsibility to continue in the safest way possible.

Are there generational differences between the attitudes of stunt people?

I’ve found this weird thing where I sit between the two. I’m not the new generation, but my experience was more with an older generation than it would have been in America because I was in New Zealand. We were a little bit behind; the technology hadn’t reached. We were still a little bit ... I don’t mean “cowboy” in the irresponsible way, I mean cowboy in the “Fuck, let’s give it a go” kind of way. But there are performers out there now, and most of their performance career has been flipping on wires, maybe on a green screen, lots of motion capture. The experience required is quite different to what it used to be.

Now, people aren’t doing back falls as much, but they are being smashed into buildings two stories up. There’s a different level of required pain in jobs and each generation feels like the next generation has it too easy. Your parents are like, “You kids have got it so easy.” And then you’ll probably say that about your kids. Your kids will probably say that about their kids, until the world explodes and then no one cares.

I think that’s probably why that balcony fall and this project was so exciting, because it was an opportunity to step outside of the polished, flawless action world and just get a little bit more rough and tumble again.

I hadn’t really thought about it this way before, but the second half of Death Proof with the car chase could be seen as a metaphor about different generations of stunt performers, where the older generation is a little wilder and thinks it’s fun to push the limit of responsible danger, while the younger generation thinks the old way of behaving is going to get them killed.

There’s an element of modern-day people that think they are taking it more seriously than—and I’m using air quotes here—the “cowboys” used to. But then the cowboys can turn around and say, “We’re way tougher than you because we didn’t use pads.” My basic feeling is if you’re going to be good, no matter what area you’re in, you need to have an appreciation and a respect for where you’ve come from and have a respect for those that are taking the torch and running with it. I do have a little bit of the old school in me where I’m like, if you’re not willing to eat shit and hit the ground occasionally in the middle of your job, then I personally think you’re spoiled. But that’s just me.

In Death Proof there’s the scene where Stuntman Mike talks about working on shows like The Virginian and High Chaparral, which are the type of shows that Cliff could have worked on. Cliff is a hero in Once Upon a Time ... Hollywood, but was it ever talked about that there might be a sinister side to him? You get it a little bit during the scene of him with his wife on the boat.

There were conversations around him being a war vet and the alleged killing of his wife, but in the same way we were discussing his relationship with work and his relationship with his dog and how long he had his dog and all that stuff that may or may not have any holding on anything. But no, I personally never read sinister into Cliff. I may be projecting, because I kind of fancy that if a woman could be a Cliff back in 1969, I might’ve been a bit of a Cliff. I liked that idea, but instead I was the stunt coordinator’s wife telling Cliff to get fucked, which was kind of awesome, too.

Eric Ducker is a writer and editor in Los Angeles. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.