VOD With Cheese: What the Hell Happened to John Travolta’s Career?

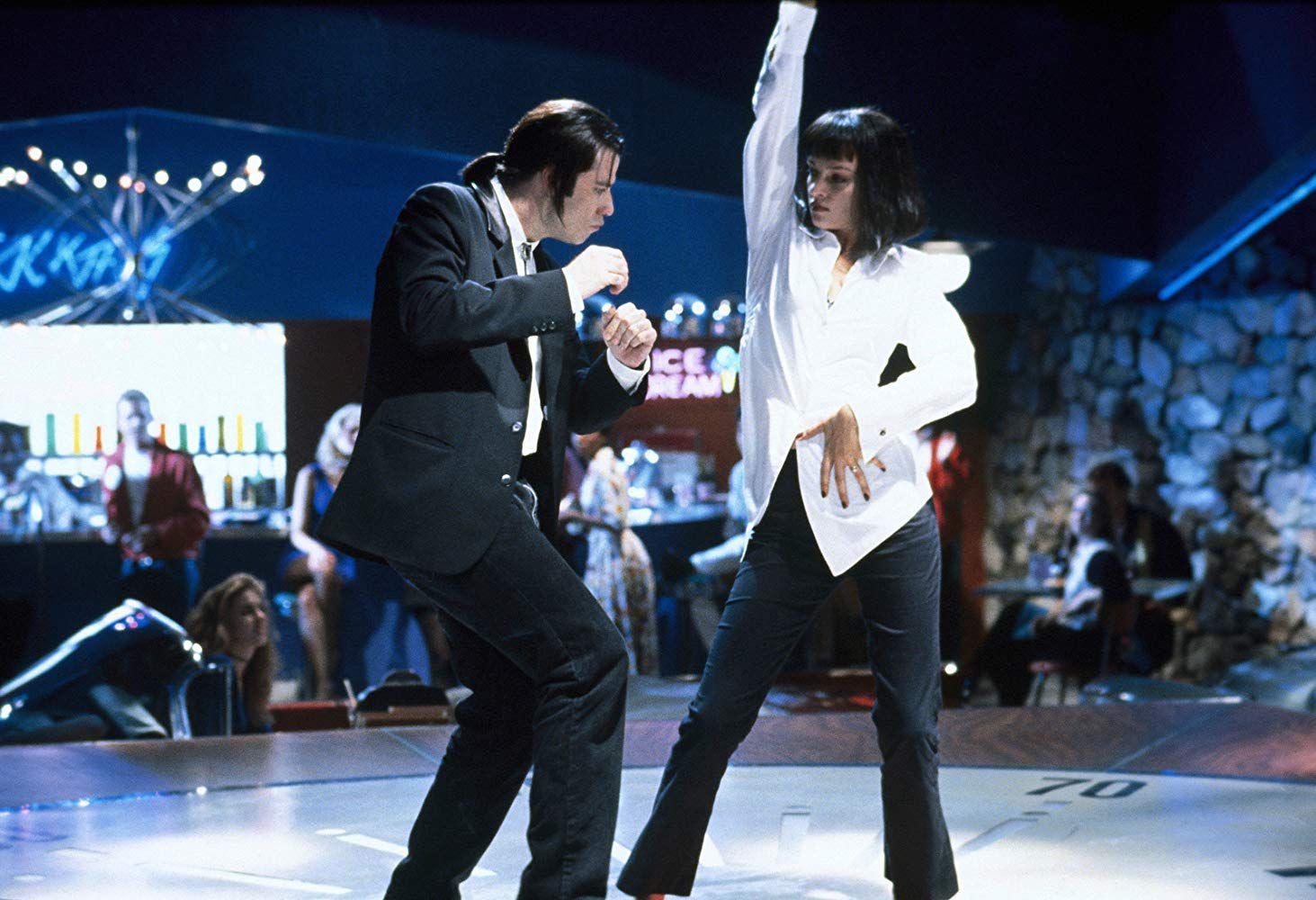

Twenty-five years ago, ‘Pulp Fiction’ revived John Travolta. Now, after decades of hits, he’s stuck in a straight-to-video void. Is Travolta’s phenomenal movie-star run finally finished?Last spring marked a particularly feverish period for John Travolta. Over the course of a few days in May, the actor was treated to a cozy, air-kissing celebration of his decades-long career at the Cannes Film Festival. It was the same glittery locale where Pulp Fiction had brought Travolta back to big-screen life in 1994, yielding him a wealth of goodwill and good scripts, and instantly returning him to his rightful place as a leading-man Le Big Mac.

Now, nearly a quarter-century later, Travolta was once again the toast of the Riviera, where cameras trailed the then-64-year-old star everywhere he went: Dancing on stage with 50 Cent; hosting a beachside 40th-anniversary screening of Grease; and walking his family down the red carpet for Solo. The outings were all timed to the premiere of his long in-the-works mob drama Gotti. But the ego-stoking centerpiece of the Cannes soiree was a 90-minute “Masterclass” question-and-answer session, one that found Travolta discussing everything from his name-making breakthrough Saturday Night Fever to his sci-fi catastrophe Battlefield Earth (which he still sees as a “personal accomplishment”). Just before the talk ended, a young Ukrainian filmmaker raised her hand and lobbed a query-slash-job-offer: Would Travolta ever consider appearing in a first-time director’s low-budget short?

Travolta’s response, in essence, amounted to: Hey, you never know! “As we’ve established before,” he told the crowd, “I have no hidden criteria for what I’ll do, and what I won’t do.”

That easygoing capriciousness only slightly helps explain why Travolta—once a big-studio megastar who commanded $20 million paychecks—has been relegated to the void of video-on-demand. His 2010s-era filmography is dotted with shoot-’em-ups and sports dramas featuring interchangeable, deeply silly titles: I Am Wrath. Speed Kills. Killing Season. It’s as though the actor’s been choosing scripts in a “Confused Travolta”–like style, helplessly shuffling from one cheap-looking, harebrained thriller to the next.

Travolta is still very much a pop culture draw in 2019, a guy who can dazzle festival revelers, schmooze chat-show hosts, and comfortably show off his chrome-domed noggin in a hit Pitbull clip. He even presented at this year’s MTV Video Music Awards. But the Travolta that lingers in fans’ memories—the one they want—is the actor they remember from past glories like Grease and Face/Off, not the guy making Redbox-ready dirt-car flicks like Trading Paint.

His current movie-star standing is so dismal that not even Gotti—a comeback vehicle Travolta nurtured for nearly a decade, and promoted tirelessly—wound up making less than $5 million, and earning a rare 0 percent score on Rotten Tomatoes. Still, considering Travolta’s recent track record, it’s a minor miracle that Gotti made it to theaters at all: According to Box Office Mojo, the last Travolta-starring film to open on more than a thousand screens was 2012’s Savages.

Travolta has been through these sorts of slumps in the past, so much so that his career-resurrection powers are, by now, part of his public legend—as familiar to moviegoers as his quick-draw hips and dimple-chinned smile. Yet the actor’s recent backslide has been painfully protracted, the kind that seemed unthinkable in the years after Pulp Fiction, which rescued him from a run of cruddy dramas and talking-baby movies. Back then, the headlines often employed the same Travolta-tweaking puns to describe his mid-’90s return: “Welcome Back,” “Stayin’ Alive,” etc.

They were apt descriptions of a phenomenon-like period that, for the next several years, found the actor gliding from hit to hit. Some of Travolta’s post-Pulp efforts were critical favorites (Get Shorty, Primary Colors); others were risible but forgivable crowd-pleasers (The General’s Daughter, Wild Hogs). In between came a few notable misfires, but for a long stretch, even so-so Travolta entries like Domestic Disturbance or The Taking of Pelham 123 could readily clear the $50 million box office mark.

But Travolta’s last few years amount to nothing less than a full-on retreat from mainstream filmmaking. Instead, he churns out a handful of on-demand obscurities each year, many of which would have seemed beneath him even during his mid-’80s nadir. They include everything from a hacky Death Wish rip-off to a hokey Southern noir to a virtual-reality spin-off project in which he … wanders around a horse stable.

Travolta swears he has a plan, sort of. “I don’t arbitrarily just say ‘Yes’ to something,” he explained to the young filmmaker at Cannes. “But if it had content that I believed in … I would partake in it.” And this week, he partakes in what may be his strangest effort yet: The Fanatic, a Hollywood-set horror-drama directed and cowritten by Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst, in which Travolta plays a disturbed stalker named Moose (it arrives in a handful of theaters this Friday, and will be available on demand September 6). Thanks to Durst’s involvement, Travolta’s abstract-mullet haircut, and the fact it was originally titled Moose, the film has been an object of mild online fascination for a while now. And it’s far more watchable than any of his recent VOD slogs. But among moviegoers who’ve welcomed back Travolta countless times during the past 40 years, there remains a question far too indelicate for a ritzy Cannes Q&A: What the hell happened to John Travolta’s career?

In the opening lines of a June 1978 cover story on Travolta, Rolling Stone predicted what the future would hold for the young star: “He will be revered forever,” the magazine declared, “in the manner of Elvis, James Dean, [and] Marilyn Monroe.”

Travolta was only 24 years old at the time, with barely a handful of feature credits to his name. But he was fresh off another season of Welcome Back, Kotter, the smash sitcom whose fans were sending him more than 10,000 letters a week. And his discofied romance Saturday Night Fever was still playing around the globe, having become an Oscar-nominated mainstream sensation, despite its dark subject matter. Within just a few days of that hype-fueled Rolling Stone piece hitting newsstands, Grease overtook theaters, and suddenly, Travolta was shaping up as the biggest male movie star in the world. “He was so huge when he came out,” Quentin Tarantino later remarked. “He actually shared something that only [Marlon] Brando had had before him, and only Julia Roberts has had since him: Any part that was even remotely, halfway conceivable that he could play, was immediately sent to him.”

Travolta’s first burst of fame came via a network sitcom, but he was built for the big screen: handsome and wavy-haired, to be sure, but with a barely contained broodiness (a Time magazine cover story, also from 1978, compared him to Montgomery Clift). And he arrived just as many of the decade’s other leading men—Eastwood, Reynolds, McQueen—were entering middle age, and when a new generation of movie stars had yet to fully emerge. “There was no competition,” Travolta later said of his early ascent. “There was no Tom Hanks yet, no Mel Gibson yet.”

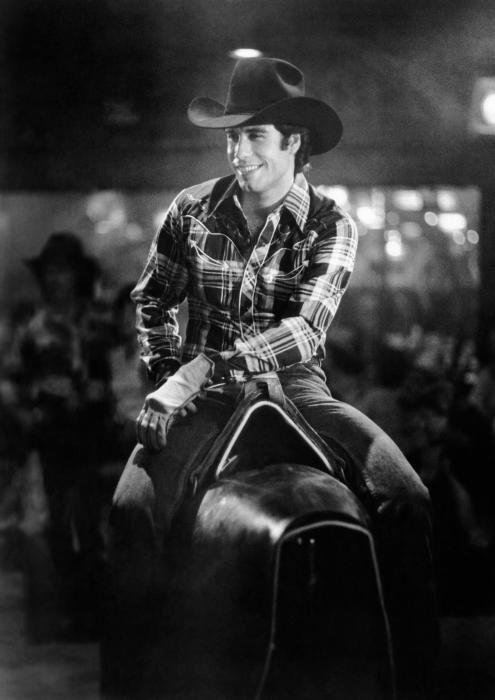

Travolta would leverage that luxury throughout the late ’70s and early ’80s, turning in sound, star-power-affirming performances in the honky-tonk romance Urban Cowboy and the conspiracy thriller Blow Out (one of Tarantino’s all-time favorites). He also began studying aviation, a pursuit that briefly took him out of the running for a few massive roles. “Imagine you finish Blow Out and the studio wants you to do An Officer and a Gentleman,” he recalled in the mid-’90s, “and you say, ‘No, I’m going to become a pilot.’”

The Officer producers were willing to wait, but Travolta was up in the air for so long that the role eventually went to Richard Gere—who’d first broken out in 1980’s American Gigolo, another showy part Travolta walked away from. The list of films that Travolta almost made over the decades would soon become legend, presenting all sorts of alternate pop-culture-timeline possibilities: Travolta as the mermaid-romancing hero of Splash; or as the avuncular shrink in Good Will Hunting; or the melodic, melodramatic recluse in The Phantom of the Opera. (Also in Travolta’s discard pile: Midnight Express, As Good as It Gets, and Chicago.) “Big movies were offered to me, and I said no,” he explained, calling it his “bad habit.”

So what did Travolta say “yes” to in the 10 years after Grease? A sweaty, oversexed Saturday Night Fever sequel (Staying Alive) and a sweaty, oversexed aerobics-romance-thriller (Perfect). A KGB comedy that played in just three states (The Experts), and a drug-gang drama that never even made it to theaters (Chains of Gold). He also starred in a trio of Look Who’s Talking films—massive hits, but hardly the kind of work that once prompted New Yorker critic Pauline Kael to praise Travolta as “an original presence.” Another of Travolta’s longtime champions was critic Gene Siskel, who offered some advice for the actor in a depressing 1989 Los Angeles Times profile that depicted Travolta as overweight, underappreciated, and far off course from casting directors’ radars. “He should be gritty—and R-rated,” Siskel advised. “He should be realistic again.”

It wasn’t until Tarantino, hot off 1992’s Reservoir Dogs, tracked down his former hero that Travolta himself began to reconsider where his career had gone: “[Tarantino] kind of rekindled the concept that I was considered a very good actor,” he said of the talks that eventually led to the very gritty, very R-rated Pulp Fiction. Travolta’s turn as the dopy, doped-up hitman Vincent Vega would land him a Best Actor nomination, and introduce him to a group of teens and 20-something fans who previously knew him mostly from Kotter reruns, Look Who’s Talking flicks, and Shake Shack sing-alongs. “I just gave John a role like the ones he used to do,” Tarantino said, “and I took him seriously.”

He also gave Travolta advice on choosing scripts, steering him toward roles deserving of his bright-eyed charm and medium-cool menace. It was Tarantino who helped sway the actor to play a people-savvy loan shark who goes Hollywood in Get Shorty. And he guided Travolta to the works of John Woo, the Hong Kong ultra-action auteur who’d convert the star into an action antihero with the back-to-back gonzo combo of Broken Arrow and Face/Off. (Alas, Tarantino also talked Travolta into the clumsy, now hard-to-find race-relations drama White Man’s Burden—a quickly forgotten setback).

By the end of the ’90s, Travolta was back to where he was during the Fever era: Any part that was even halfway conceivable for him to play was sent his way. He was making giant paychecks, and was well worth the price: Travolta’s name had brought out audiences to the new-agey summer drama Phenomenon, as well as the angel-among-us comedy Michael (the latter of which Steven Spielberg had advised him to do). “I can’t keep up with it,” he said at one point in the ’90s. “On Friday, I got 17 offers. I haven’t had 17 offers in my life.” He added: “It’s exciting, but my concern is: Am I prince for a year, and now it’s all over? It’s been 18 years since Saturday Night Fever, so I thought, ‘Will it be another 18 years?’”

What makes Travolta’s lackluster decision-making so mystifying is the fact that the actor is famously picky. It took six months for him to be talked into doing Pulp Fiction, which he signed to do only after consulting with friends. (“I thought it was probably the best part I’d ever been offered,” he told Charlie Rose. “However, I was not sure exactly what the moral message was.”) He spent 14 months considering a supporting role in 2007’s Hairspray, keeping producers waiting until just before midnight on the day he had to decide. Even his turn at Robert Shapiro in the 2016 miniseries American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson—by far his most-seen and best-received work in a decade—required Travolta to seek guidance from the likes of Spielberg, Hanks, and Oprah Winfrey, among others.

So why couldn’t any of his friends talk him out of Battlefield Earth, the rat-brained, super-expensive schlocker that crashed in theaters, ominously kicking off Travolta’s 2000s? And who convinced him to give a thumbs-up to Be Cool, his warmed-over Get Shorty sequel? Sometimes Travolta simply had bad luck, teaming with ace filmmakers (Costa-Gavras, Nora Ephron) on some of their career-worst films (Mad City, Lucky Numbers). In other instances, he said, his decisions were strategic, making mainstream films like Wild Dogs so that he could “get permission” for smaller, more personal efforts (some of which also failed, like the 2004 drama A Love Song for Bobby Long).

It wasn’t just iffy decision-making that hurt Travolta. By the time the 2010s arrived, the studios had little interest in the kinds of one-off, adult-targeted films Travolta had made only years earlier, when a firefighter drama like Ladder 49, or a seminaughty action flick like Swordfish, could make $100 million worldwide. The franchise era was dawning, and many of Travolta’s peers and competitors—like Jeff Bridges and Harrison Ford—pulled back on starring roles, moving on instead to IP entries or high-profile ensemble parts (or both). At the same time, other leading men of a certain age, like Michael Douglas, Kevin Spacey, or Anthony Hopkins, headed to television.

But Travolta? He went straight to video.

Earlier this month, Travolta showed up on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, where he and the host competed in a “John Travolt-Off,” in which both men re-created some of the actor’s best-loved roles. Pulp Fiction’s Vincent Vega was spotlighted; so was Grease’s Danny Zuko and Face/Off’s Castor Troy.

But there was no mention of the Serbian hitman Travolta played in 2013’s little-seen Killing Season. Nor the anguished lineman from 2016’s Life on the Line. Not even the boozy private dick from this year’s The Poison Rose. Travolta has averaged two to three such films in the past few years, and they make for confounding viewing, as they often find him donning a brazenly synthetic new hairpiece and/or hard-to-place, Southern-gumbo accent. It’s almost as though he’s stuck playing the same character in one never-ending cheapo flick, wandering from one tax-credited filming location to another.

It’s impossible to know exactly why Travolta insists on making these barely there films, rather than focusing on the ensemble work for which he’s clearly adept (both Hairspray and The People v. O.J. made the case for him as an ace scene stealer). Perhaps the aviation-loving actor needs the money, like his lavish-living Face/Off costar Nicolas Cage. Maybe he just feels the need for speedboat flicks and racing dramas. There’s also, of course, the unsettling possibility that producers see Travolta as an iffy hire: The actor has faced troubling legal accusations in recent years, including a 2012 sexual-battery suit that was later dropped.

It’s more likely, however, that Travolta’s recent career moves are simply proof that he wants to be revered forever—but only as the full-on movie star he once was, and is clearly trying to be once again. His VOD-movie performances may not match the chilled-out sexiness of Pulp Fiction and Saturday Night Fever, nor the hammy heights of Face/Off or Swordfish. Yet even in his junkiest efforts, you can see Travolta working hard to Travolta-ize each scene, adding some unexpected bit of physicality or warmth that another actor may not have even attempted (by comparison, his fellow Pulp alum Bruce Willis often spends his VOD efforts in a state of maximal minimalism, often looking as though he’s grumpily waiting the signal that his check has cleared).

Travolta’s ultracommitment is apparent in The Fanatic, a movie that finds him playing his quietly crazy stalker-character, Moose, with a mix of under-his-breath rage and giddy lunacy. At one point, his character breaks into a star’s home, finds a pair of antlers, and runs around sing-songing “Heeere’s Moosey!” (It should be noted that, in addition to his obscenely ugly haircut, Moose sports gaudy printed shirts, and talks with the cadence and impetuousness of a 12-year-old.) Travolta is clearly enjoying playing such an unhinged outsider, but still: Why The Fanatic? Why a character named Moose? Maybe Travolta, who coproduced The Fanatic, sees the film as along the same continuum as Pulp Fiction—another violent tale of Los Angeles lowlifes that allows Travolta to subvert moviegoers’ expectations. Or maybe, like so many actors of his generation, he just can’t stop going: In late 1995, back when he was at his 17-offers-a-day peak, Travolta was asked what he wanted most in the next year. His reply: “I hope I keep working.”

The Fanatic is so out there, it will likely become an object of curiosity upon its release (it’s already generated more prerelease attention than any other recent Travolta effort). It may also be the last we see of the star for a while. For the first time in years, his IMDb page doesn’t have any pending projects listed, meaning his straight-to-streaming days might be reaching their end. It’s almost as if he’s back to where he was in the late ’80s, when he’d all but disappeared from view. That was a fallow period, to be sure. But it also set up Travolta for one of the greatest showbiz second acts (or was it his third act? Or fourth act?) of all time.

Given his historically troubled trajectory, it’s a good bet Travolta’s got one more comeback left in him. The big studios may not make too many Travolta-friendly movies nowadays. But they also don’t make many Travoltas anymore—the kinds of stars who can lay claim to having charmed multiple generations of fans. Surely, there’s a place for him somewhere in circa-2019 Hollywood. He could very well revive himself as a streaming-series heavy, or rebrand as a scene-chewing supporting player. But to declare his career finished? That’s a bold statement—and one John Travolta has proved wrong plenty of times before. “Reinvention,” he reminded the Cannes audience last year, “is what I am about.”