In 1919, Babe Ruth hit 29 home runs, a new single-season MLB record. Before him, only two 20th-century players had even hit 20 home runs in a season: Gavvy Cravath and Frank “Wildfire” Schulte. In 2019 alone, 93 players have already hit 20 home runs or more, with a month left to go in the season. This is a profound statement on how much baseball has changed in the past 100 years, nearly as much so as the modern game’s regrettable paucity of players named “Babe,” “Gavvy,” and “Wildfire.”

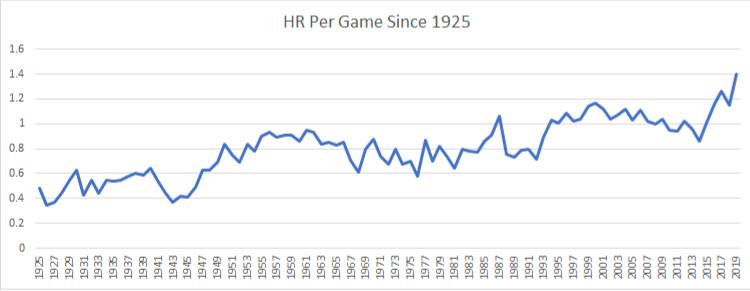

It’s a well-documented fact that baseball is more home-run-heavy now than at any point in its history; balls are leaving the yard at a rate of 1.4 per team per game, surpassing the previous record of 1.26, set in 2017. From the start of the expansion era to 2016, the leaguewide home run record increased by 0.22 home runs per team game. From 2016 to 2019, the record home run rate increased by 0.23 home runs per team game.

Just as in the last home run spike, the steroid era of the mid-1990s to mid-2000s, there is a specific cause: in this case a juiced ball, rather than juiced ballplayers. Certainly today’s athletes are also bigger and stronger than their predecessors—Aaron Judge has nine inches and more than 110 pounds on Willie Mays, for example—and modern player-development techniques emphasize putting the ball in the air, which obviously leads to more home runs. But primary responsibility for the home run spike rests with a change to the baseball itself; starting in mid-2015, baseballs started jumping off big league bats as if they were filled with springs. MLB commissioner Rob Manfred denies that the league is intentionally juicing the ball, but told reporters at this year’s All-Star Game that MLB is looking into changing the ball’s specifications, presumably to counteract the unintentional home run explosion of the past few years.

The new ball—or balls, as the ball has evolved over the past five seasons—has lower seams, a less dense and better-centered core, even smoother leather. The result: Batted baseballs have less drag and are more stable in flight, and therefore go farther than they used to when hit. No two balls are exactly the same, and indeed the minute variations MLB allows in its official baseballs have led to changes that are imperceptible from ball to ball, but on the aggregate radically transformed the offensive landscape of the sport.

According to FanGraphs, the five highest leaguewide HR/FB rates since the beginning of the PITCHf/x era in 2002 have come in the past five seasons. This year’s HR/FB rate, 15.3 percent, represents a more than 10 percent increase on the previous high, 13.7 percent, set in 2017, and is more than 60 percent greater than the leaguewide HR/FB rate of 9.5 in 2014, the last full season played without the juiced ball.

Leaguewide home run totals, broadly speaking, have been on the rise ever since the live ball era began 100 years ago, with a few year-to-year fluctuations as the game has evolved.

In 1925, the first year for which Baseball-Reference has detailed year-by-year home run data, homers were a little more than a third as common as they are now; in the second year of the sample, 1926, the average MLB team hit just 0.35 home runs per game, the lowest in the sample. Visible in the graph are troughs for World War II and the second dead ball era of the late 1960s, and a post-strike spike as the PED era took off in earnest.

In 1998, baseball’s last expansion year, MLB crossed the 5,000-homer threshold for the first time. That’s also the year of the great home run chase, when Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs, breaking Roger Maris’s long-standing record, and Sammy Sosa won NL MVP with 66 home runs. It’s also the first of two years in which four MLB players hit at least 50 home runs in a season. The other time that happened, 2001, the single-season home run record fell once again, to Barry Bonds with 73.

In 2017, MLB crossed the 6,000-homer threshold for the first time, but nobody’s come close to making a run at Bonds’s record. In fact, the only player to get within spitting distance of Maris’s old record in the juiced ball era is Giancarlo Stanton, who hit 59 home runs in 2017. That’s going to stay true in this record-setting home run year, as Mike Trout, who leads the league with 43 home runs, would need 31 in the Angels’ last 27 games to beat Bonds, and 19 to beat Maris. That’s pretty much impossible, even with this ball, and even with Trout.

There have been 45 individual 50-homer seasons in MLB history. More than half of them happened between the strike and the publication of the Mitchell Report in 2007, the unofficial end of the steroid era. Of the eight 60-homer seasons in MLB history, six came in the steroid era. Somebody’s going to get to 50 this year, whether it’s Trout, Pete Alonso, Cody Bellinger, or some other slugger with a monster September. But the current home run binge won’t result in a new home run king anytime soon.

It’s frankly somewhat puzzling that with the league on pace to hit almost 600 more home runs than in any previous season, and more than 1,000 more than in any season before 2017, nobody’s taken a run at the single-season home run record. But perhaps that speaks to the nature of the juiced ball, and how it differs from PEDs in terms of how it affects home run totals.

PEDs differ from the juiced ball in two important ways. First, they affect home run totals by offering substantial personal gains to those who use them. McGwire was always an incredibly powerful hitter, but in the late 1990s the famously injury-prone slugger was able not only to increase his strength but to stay in the lineup long enough to hit 60 or 70 home runs a year. Barry Bonds was able to include immense power gains and longevity to his already bountiful stable of gifts, which made him one of the best hitters in MLB history even before he touched the cream or the clear.

Second, PEDs are opt-in, and many players, even most, either didn’t use them or didn’t use them enough to benefit conspicuously. The juiced ball is part of every hitter’s life whether he likes it or not.

While PEDs allowed the best home run hitters in the league to turn into dinger-mashing supermen, the tide of the juiced ball is lifting all boats. In 2000, at the height of the steroid era, 217 players hit at least 10 home runs. In 2017, 242 hit at least 10 home runs and 117 hit at least 20, a new record. This year, with a month and change left to go in the season, 237 players—36.7 percent of position players with at least one plate appearance—have reached double digits in home runs.

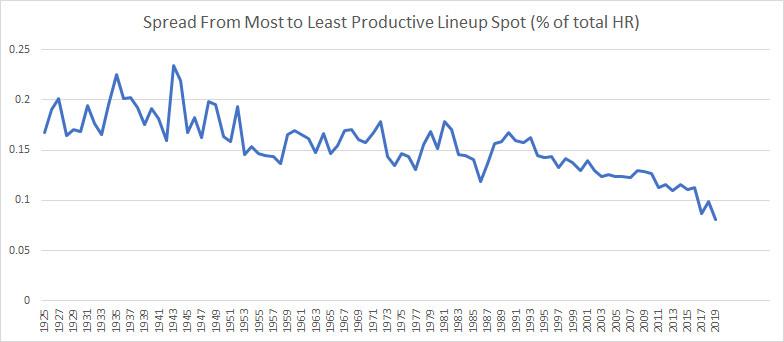

Baseball-Reference splits out each home run based on which spot in the lineup it comes from, allowing us to determine what percentage of the league’s total home runs came from each position in the order.

In 1927, 21.1 percent of home runs leaguewide came from the no. 3 spot in the lineup—the start of B-Ref’s data set. This is a direct result of Babe Ruth, who started 151 games in the no. 3 hole that year, accounting for 6.5 percent of MLB’s home runs all on his own.

Most of the time, the most productive home-run-hitting spot in the lineup has been the cleanup spot, leading all lineup spots 92 times in the past 95 years. The most recent exception is 2001, when Bonds and Sosa posted the highest and fifth-highest single-season home run totals ever, and 125 of their combined 137 home runs came out of the three-hole. No. 3 hitters out-homered cleanup hitters that year, 1,012 to 961.

The batting order position that produces the least home runs is usually the ninth spot, which is quite intuitive. But whatever the position, measuring the difference between the most and least homer-heavy spots in the lineup is a good indication of how evenly leaguewide power is spread through the batting order.

The gap between lineup spots has generally been on the decline since 1925, but it’s taken a precipitous drop under the juiced ball. Even in the steroid era, cleanup hitters usually accounted for somewhere between 17 and 19 percent of home runs, as opposed to nine-hole hitters, who produced 4 to 5 percent of home runs. The gap between the most and least home-run-productive spots in the lineup, one through nine, had dropped below 13 percentage points once from 1925 to 1999 before resting in that range in the early 2000s. It went under 11 for the first time in 2013 (but only just, at 10.94 percentage points), but has been below 10 percentage points each of the past three seasons.

In 2019 so far, cleanup hitters account for 14.6 percent of home runs, barely the second-lowest mark of all time behind 2017, while no. 9 hitters account for 6.5 percent of home runs, the highest mark of all time by half a percentage point. That gap, 8.1 percentage points, is by far the lowest in MLB history.

The best way to express the egalitarian nature of the ball-induced home run spike is also the most interesting tactical outgrowth of that binge: Namely that there isn’t such a thing as a heart of the order anymore, since power is not only more common but spread more evenly than at any point in history. The days of the leadoff hitter as a table-setter have come and gone. Leadoff hitters have hit at least 600 home runs each of the past three seasons, after never hitting more than 466 in any season from 1925 to 2015 and getting out-homered by nine-hole hitters in 1927.

It’s an accepted bit of baseball wisdom that the end of the dead ball era led to changes in pitcher usage because pitchers were once able to coast through less dangerous hitters, allowing them to conserve their energy and pitch more innings total. Once every batter in the lineup became a threat to hit a ball over the fence, that changed. If only they knew then what we know now. In 2014, MLB teams used a record 692 pitchers; this year, with a month to go in the season, they’ve already used 792. The home run explosion is almost certainly not the biggest factor in the massive increase in the number of pitchers needed to get through a season, but it takes greater individual effort and greater attention to matchups to navigate a lineup where every hitter is a dire threat to go yard.

The intentional walk and sacrifice bunt, both of which were falling out of favor already, make next to no sense when all nine hitters can hit home runs. Five teams have executed fewer than 10 sacrifice bunts this year, and six have called for fewer than 10 intentional walks; in fact, the Astros haven’t given out a single free pass so far in 2019. Before this year, only seven teams since 1901 had pulled off fewer than 10 sacrifice bunts in a season, and only five teams had issued single-digit intentional walks since B-Ref started tracking the stat in 1955.

The extent to which the juiced ball has thrown baseball into chaos underlines the difficulty of predicting a game held in such delicate balance, to say nothing of the difficulty of comparing players across eras. But teams and players have been operating under this new paradigm that they—and we, as viewers—are adapting to the new normal. This new normal is having every bit as extreme an impact on the game as the steroid era, and if MLB ever tweaks the ball back to its pre-2015 form, the juiced ball era will leave a similarly strange statistical legacy for baseball fans of the future.

Statistics are current through Wednesday’s games.