Until this month, 31-year-old Mets minor league knuckleballer Mickey Jannis had never struck out more than nine hitters in any of his 130-plus career games in affiliated ball. He hadn’t topped eight since 2017. But on August 13, in a start for Double-A Binghamton, Jannis struck out 10 batters in six innings and walked only one. In his next outing, he struck out 12 in seven innings, again walking one and allowing four hits. His next start went well, too: He struck out only five but threw eight scoreless innings. And on Wednesday of last week, he pitched a complete game against Portland and struck out 10 again.

Through August 1, Jannis owned an 8.2 percent strikeout minus walk rate in 16 games this season spread across Double-A and Triple-A. In his last five games, he’s more than tripled that to 24.8 percent. And in his last 30 innings, Jannis has struck out 37 with a 0.90 ERA, a 0.83 FIP, and a 1.41 FIP. Where the heck did all those Ks come from?

As is often the case in baseball’s era of data-driven development, a player’s sudden, dramatic improvement was precipitated by a piece of technology. Before his breakout, Jannis had given up 45 hits in his last 25 innings, along with nine walks and only 13 strikeouts. He wasn’t getting whiffs, and worse, he says, his catcher wasn’t having trouble corralling his signature pitch, which is supposed to be unpredictable. He knew the knuckler needed help.

For knuckleballers like Jannis, though, help has historically been difficult to find. Jannis was selected by the Rays in the 44th round of the 2010 amateur draft—the second-to-last draft that went farther than 40—and lasted two seasons in their system before being released. He landed in the independent leagues, and inspired by R.A. Dickey’s 2012 Cy Young season, he devoted himself to the knuckleball. In 2015, Dickey’s former organization signed him out of the Atlantic League. But by then, Dickey had moved on, and no knuckleball mentor remained. “I’ve pretty much been on my own the entire time,” Jannis says. “Just trial and error and feeling for it and throwing it as much as I can just to keep that feel going and learn what works.”

Jannis still lacks an expert instructor for his specialized pitch, but he does have a helper in the form of a compact blue box: an Edgertronic camera. These high-speed, high-definition devices have flooded into baseball in the past few years as prices have fallen and players and teams have discovered the benefits of being able to scrutinize players’ slow-motion movement in unprecedented detail. The cameras have become indispensable to the pitch-design process, and allow pitchers to perceive (and modify) aspects of their delivery and release that can’t be captured with the naked eye or conventional cameras.

Although some organizations have installed Edgertronics throughout their minor league systems, Jannis says in-game, high-speed footage isn’t accessible to his team. But there is an Edgertronic in his Double-A bullpen, and that’s where he headed after giving up nine hits and lasting only 4 2/3 innings on August 1. Jannis threw while the camera recorded him, and he and his pitching coach studied the footage that revealed what had gone wrong.

“I was just pulling off a little bit early with my front side,” Jannis says. “It was almost like I was trying to throw a fastball too hard … and that was causing me to get around the knuckleball. And with the knuckleball, you really want to stay behind it and on top and stay through the pitch. When I was able to see that visually, it just kind of clicked in my head that I needed to stay behind it a little bit more.”

Jannis, who also started throwing his knuckler harder (especially with two strikes), describes the mechanical cleanup he made as “the slightest little adjustment.” But it’s clearly been a crucial one. “I threw the one bullpen and I’m like, ‘OK, I’m starting to get it,’” he says. In his next outing, when he went seven innings, it was “a lot better, but it still wasn’t all the way there yet. And then the next game I went out and I think I had 10 strikeouts, and we were like, ‘All right.’” Before the adjustment, Jannis’s knuckler was rotating too much side to side. Since then, he says, “It’s just been coming out really good, with no spin, and dancing.” And the hitters, he adds, are “just missing it.”

The knuckleball’s unique appearance and properties have earned it a privileged place in baseball lore. We love it largely because it empowers middle-aged, unathletic-looking dads who don’t seem to belong in the big leagues, and it helps them hold their own against physical specimens with monstrous swings or far loftier radar readings. We root for those knuckleballers because they’ve snuck through a back door to baseball that we wish would open for us, and these players never become common enough to wear out their welcome. But the knuckleball’s novelty leaves it vulnerable to banishment, and its toehold has never appeared more precarious than it does today. As Jannis’s recent renaissance suggests, though, the art of the knuckleball is trending toward science. And while Hoyt Wilhelm may not have needed a camera to perfect his floater, technology could be the key to preserving a scarce and precious pitch.

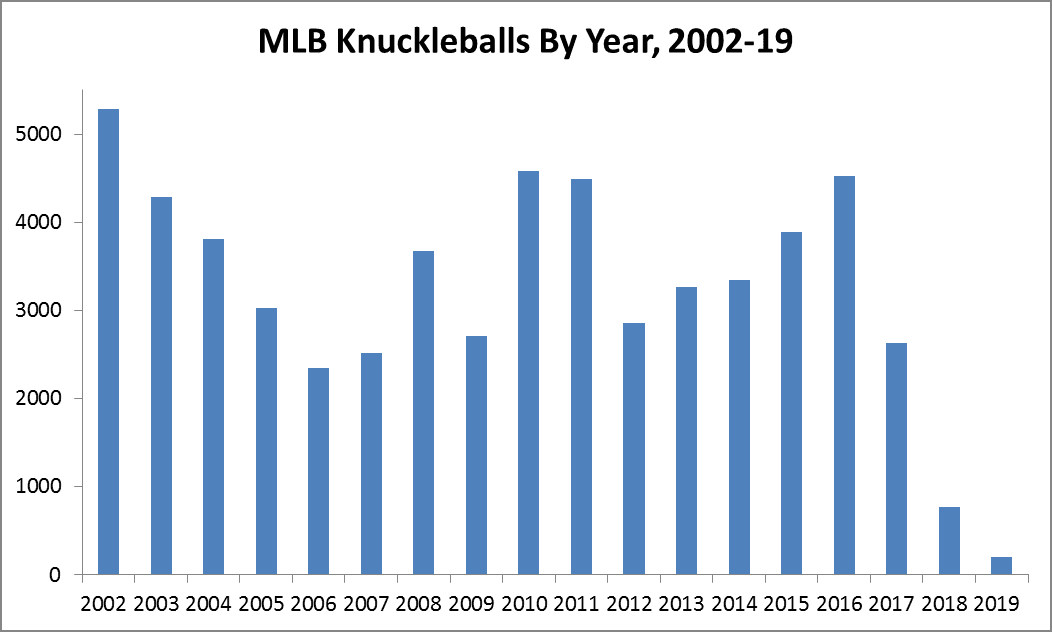

In February, FanGraphs noted that the knuckeball is “an endangered species.” In June, a Wall Street Journal opinion piece asserted that it’s “close to extinction,” and earlier this month, The Washington Post lamented that it “may be nearing extinction.” That’s a tempting conclusion to draw, given that the knuckleball has been thrown far less frequently at the major league level this season than in any previous year for which we have pitch-type data. Only a little more than 200 pitches separate the knuckleball from the screwball, which hasn’t been sighted this season.

Only two dedicated knuckleball pitchers have spent time in the majors this season: 34-year-old Ryan Feierabend, a recent knuckleball convert who pitched two games for Toronto in May before returning to Triple-A, and the oft-injured Red Sox swingman Steven Wright, who turned 35 on Friday and spent his birthday nursing an elbow injury that may end his season. Neither Feierabend, who twice went five or more seasons between big league appearances, nor Wright—the only player to be suspended for violating both MLB’s PED policy and its domestic violence policy—is a suitable standard-bearer for the niche pitch, which has led to the current crisis.

Although the raw numbers make the knuckleball’s future look grim, it’s helpful to have some perspective on its past. Writers have been pronouncing the knuckleball near death for decades, despondently citing the advanced ages of its active adherents and pooh-poohing the possibility that successors could arise. “The knuckleball is becoming an endangered species in baseball,” wrote the Arizona Daily Star on May 30, 1982. Two years later, Murray Chass said the same in The New York Times. In March 1988, with both Niekro brothers either retired or about to be and Charlie Hough 40 years old, the Los Angeles Times wrote that knuckleballers were “as endangered as the … Siberian Tiger.” In 1989, Canada’s Financial Post called Hough “the last of a dying breed” and predicted that the knuckleball would join the list of extinct species “before the page is turned on this century.”

1991 was a big year for knuckleball death notices: The vultures circled Tom Candiotti and the 43-year-old Hough in the Ottawa Citizen in June, the San Francisco Chronicle in July, and the New York Daily News in August. The Palm Beach Post dropped an “endangered species” in January 1997, as did the Fort Collins Coloradoan (which also prematurely predicted the death of football’s drop-back passer) in October 2003 and the Gannett news service in July 2006, when Tim Wakefield was briefly the lone knuckleballing big leaguer. The Associated Press shoveled dirt on the knuckleball’s casket in 2011 and in 2017, Dickey’s last season.

Yet in 2019, the Siberian tiger is still alive, and so is the knuckleball, albeit barely. (We can’t say the same of the Financial Post, which didn’t survive the last century.) The knuckleball is perpetually—and, thus far, mistakenly—reputed to be on the way out partly for one of the same reasons that baseball itself is: It’s typically preferred by an aged audience. Almost no pitcher enters the pro ranks as a knuckleball pitcher; some knuckleballers don’t start out as pitchers at all. Players transition to knuckleballing as a last resort, often relatively late in their careers. They don’t make top prospect lists, so we seldom see them coming; Wakefield, who was drafted as a second basemen, was primarily a position player until 1990, but by 1992 he was hurling knucklers in the Pirates’ rotation.

Thus, the next generation of knucklers is always inchoate. And the current generation is never robust, because the pitch is perplexing to pick up and even more vexing to master. Baseball’s infrastructure caters to conventional players, and knuckleballers are forced to fight both implicit bias and institutional resistance to the troublesome pitch: Scouts can’t scout it, coaches can’t coach it, and catchers can’t catch it. The knuckleball’s only evolutionary advantage is that it’s almost as difficult to kill as it is to create. The low-speed pitch places little stress on the arm, which has enabled some of the select few who’ve harnessed its power to pitch effectively into their 40s. When a knuckleballer breaks through in his 20s, as the Niekros, Hough, and Wakefield did, he can carry the torch for 15 years or more, until long after he looks too old to be on a baseball card. Even so, the line of succession is rarely secure.

Traditionally, the strategy for ensuring the survival of the species has been similar for knuckleballers and panda bears: Put two or more together in a controlled, safe setting and hope they reproduce. The knuckler code dictates that today’s knuckleball thrower is tomorrow’s knuckleball teacher: Once a pitcher reaches knuckler nirvana, he’s obligated to the brotherhood and expected to pass on his wisdom for the rest of his life. That’s still true; Feierabend has gotten guidance from Dickey (his former teammate), and Jannis has communed with Candiotti and Wright. But maybe new tech can complement or fill in for an audience with a knuckleball oracle.

“It is such a feel pitch, and sometimes … you lose a little bit of feel or understanding about where your hand is on the baseball,” says Charlie Haeger, a knuckleballer who threw 34 games for three teams in the majors from 2006-10 and served as the Rays’ pitching coordinator from 2016 to 2018. “So, the high-speed camera’s extremely valuable. … You can really see if you’re imparting any spin directionally.” Haeger says the Rays started using the cameras extensively in 2018. “Once we started to get that footage, just to see some of the adjustments that we could make on the fly from pitch to pitch, say in a bullpen session or in a training session, that would make some distinct improvements.”

As Red Sox assistant pitching coach and vice president of pitching development Brian Bannister told me last year, “Pitching is not mysterious, it’s just physics.” Although the knuckleball seems more mysterious than most pitches, it’s still bound by the same rules. Bannister, a former non-knuckleball pitcher who now works with Wright in Boston, explains that the knuckler requires a two-seam grip, with the seams aligned vertically and evenly. What happens next is so subtle that it’s easy to misunderstand.

“It’s a myth that you don’t want to put spin on a knuckleball,” Bannister says. “The pitcher is trying to impart some slight horizontal rotation on the ball so that those two vertical seams on each side of the ball enter a state of imbalance. This causes unequal laminar flow on each side of the ball, which results in the ‘dance’ or ‘butterfly movement’ effect that is so valuable to fooling a hitter. A four-seam grip or a knuckleball with no spin never enters into this on again, off again state of imbalance that adds so much value to the randomness of both the batter’s visual experience and the absolute pitch path.”

When designing a conventional pitch, players try to pair a high-speed camera with pitch-tracking tech like TrackMan or Rapsodo. The combination of cameras and radars enables pitchers to examine how each offering came out of the hand, measure its spin and movement to assess how close it came to the desired result, and then adjust the grip or release accordingly. That doesn’t work with knuckleballs, which confound humans and machines alike. “Rapsodo is only taking images several hundred frames per second, and TrackMan uses a fitted-pitch path model, so they both add little to no value in designing a knuckleball,” Bannister says. “A high-speed camera or a wind-tunnel lab are much more valuable resources.”

Jannis confirms that the Rapsodo device in the bullpen registers his knucklers only inconsistently. If a knuckler’s spin rate is tracked, it’s probably a bad sign. Before he adjusted his delivery, Rapsodo was pegging the pitch’s spin rate at 200 to 300 RPM, whereas when the pitch is floating as intended, it shows up as under 100 or doesn’t register at all. When Jannis sees only slight rotation on the high-speed footage and confirms that Rapsodo didn’t detect the spin, he knows the knuckler is working.

Jannis occasionally looks at the exit speeds of hits he gives up to make sure he’s inducing weak contact, but in-game TrackMan data doesn’t help him otherwise. That’s why he values the Edgertronic’s input. “That’s the only visual I have where I can see how my ball’s rotating,” he says. Without it, he adds, “I can’t really tell the difference between one that’s really good or one that gets hit for a single or one that gets hit for a home run.”

According to data from TrackMan, Jannis, Feierabend, and Wright are three of the six pitchers who’ve thrown more than 20 knuckleballs in the minors this season. The others are J.D. Martin, a 36-year-old former major leaguer who converted to knuckleballing after his time with the White Sox and is now pitching in Triple-A with the Dodgers, who’ve had him work with Hough; Alex Klonowski, a 27-year-old part-time knuckleballer in Triple-A with the Angels; and Kevin Biondic, a 23-year-old Red Sox righty in A-ball who signed as an undrafted free agent last year after a scout saw him throw a knuckler in a college game that he had started at first base. “He said, ‘Do you want to pitch?’” Biondic recalls. “And, hey, I’ll take any offer possible, you know? Any way to get to the pros.” Knuckleballers are nothing if not adaptable.

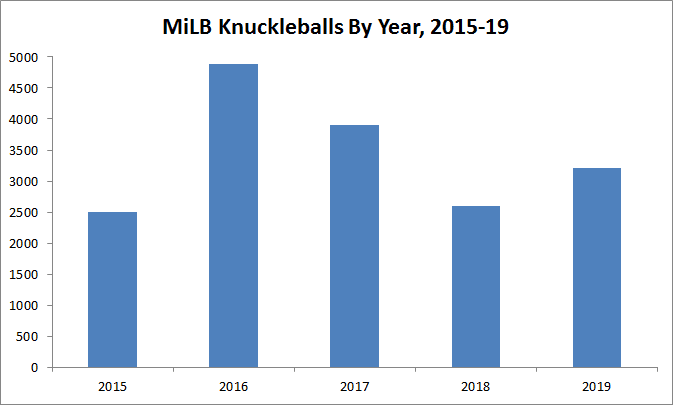

More than 3,000 knuckleballs have been tracked in the minors during this still-in-progress season, which paints a slightly less dire picture of the pitch’s usage than the MLB numbers. (TrackMan’s database also contains evidence of knuckleballers in college and the KBO, as well as a few other players who have dabbled in the dark art of the knuckler in the minors this year.)

Like Jannis, Biondic, Feierabend, and Martin have all tried out high-speed cameras this season. Feierabend, who’s only two years into his knuckleball metamorphosis, has gone from throwing the pitch 30-40 percent of the time at the start of the season to roughly 75 percent of the time now, which he credits partly to a change the camera helped him make. The left-handed Feierabend was releasing the ball with a traditional arm path that came across his body at an angle, with his hand finishing across his right knee and into the vicinity of his right hip. After watching that movement in slow motion, he adjusted his arm path on the knuckleball to come closer to a downward, six o’clock trajectory than a four o’clock trajectory.

“Every time I would finish like a conventional pitcher, the ball was doing the same thing … it would dance a little bit and then it would ultimately just be a curveball or a slider,” Feierabend says. “It had the same path out of my hand every single time. And once I realized what I needed to do as far as my arm path, the ball was more erratic. It was moving more than just to the right.”

With the Edgertronic’s assistance, one of those aspiring pitchers may make the majors and last a long time. But without a support system, a lone knuckleballer often faces an arduous journey, which is why from time to time a team will consider signing multiple knuckleballers and try to raise them together. “I had crazy ideas,” says Chris Long, the Padres’ senior quantitative analyst from 2004 to 2013. “One of my ideas, I called it ‘Camp Knuckleball,’ which was finding the failed prospects and seeing who can actually throw a knuckleball.”

That idea didn’t come to fruition for Long, but at least two teams have subsequently pursued something similar. In 2013, the Orioles hired Phil Niekro as a consultant to train a trio of would-be knuckleballers: Eddie Gamboa, Zach Clark, and Zach Staniewicz. None of the three pitched in the big leagues with Baltimore after trying to pick up the pitch. “I’m like, the knuckleball can’t be too hard. I can pitch,” Clark says. “Well, it was really hard. … As soon it leaves your hand, you really have no clue what it’s going to do. At least that’s the way I felt. You knew when you threw a good one, but a good one and a good pitch were not the same.”

With help from Haeger and director of pitching R&D Josh Kalk (who now works for the Twins), the Rays tried it too a few years later by cultivating a crop of four knuckleballers, including Gamboa. According to Haeger, the Rays believed that the knuckleball would benefit from the still air inside the dome at Tropicana Field, where Wakefield had tended to dominate. “The Rays saw that it could have been, or that it still possibly could be, beneficial,” Haeger says, adding, “So they figured, let’s give it a shot and see what we can come up with. … It was a—I don’t want to say shot in the dark, but it was a calculated jump.”

Haeger traveled to work with each pitcher in person, and the Rays’ catching coordinator put in extra time to make sure they had capable batterymates. But the program’s payoff was limited. “I knew going into it that it was going to be difficult,” Haeger says. “It’s just … a fickle pitch. I think Eddie was a success as far as the program is concerned.” Gamboa, who’s now in the Mexican League, made the majors with the Rays and pitched well in seven games at the end of 2016.

Right now, no teams are trying Camp Knuckleball, but two leaguewide trends or impending developments may make some impact on the knuckleball community. The first is home-run-related. Jannis’s current hot streak and Dickey’s Cy Young year notwithstanding, the knuckler is geared more toward weak contact than whiffs. That’s probably bad news in the age of the ultra-aerodynamic ball, which can fly over the wall without being crushed. However, while knuckleballers might be better off if they missed more bats, there is a silver lining: The perception that they’re particularly prone to fly balls doesn’t seem to hold up.

“I’m not sure if that’s accurate,” says Haeger, who continues, “It’s one of those pitches where if you have it going really good that day with a lot of depth, you create a lot of ground balls.” Wakefield was a fly ball pitcher, but Dickey and Haeger weren’t. Jannis, who has a high ground ball rate, still surrendered five dingers in his 6 2/3 innings in Triple-A this year, but there’s little evidence that knuckleballers have historically allowed higher home run rates than non-knuckleballers.

The other looming factor that may have some bearing on the knuckleball’s future is the advent of robot umps, which are being tested in the Atlantic League this season. It’s unlikely that we’ll see computer-called strike zones in the majors or even the minors in the near future, but considering the life span of successful knuckleballers, it’s certainly conceivable that someone Biondic’s age will pitch into the era of automatic zones. The consensus among knuckleballers: Bring on the robots.

“I think it will definitely benefit the knuckleball, because I find that the umpires kind of give up on the pitch … because they’re not used to it,” Martin says. “Maybe it’s high, and it drops at the last minute. Or it’s outside and it cuts back in at the last minute. And I have a lot of pitches that are on the corner that are very close that I don’t get.” Feierabend agrees, as does Jannis. “You look at the way the catcher catches it, and you’re like, ‘That pitch is never going to get called a strike because it’s way below where a catcher normally catches a strike,’” Jannis says. “So visually it would look terrible. But according to the way the strike zone should be, that should be a strike.” After one of Jannis’s two walks on Wednesday, he says, his catcher told the umpire, “If we have robot umpires, all three of those pitches or all four of those pitches are strikes.”

When Feierabend says that umps miss four or five calls on his knucklers per game, he’s not necessarily exaggerating. According to 2008-19 Pitch Info data provided by Baseball Prospectus, umps call knuckleballs less accurately than any other off-speed pitch. (Four-seamers and sinkers are called the least accurately, probably because they’re often located close to the corners, where umps give extra inches off the plate.) Knucklers have highest called-strike rate of any pitch type in the upper third of the zone and above, and the lowest called-strike rate of any pitch type in the lower third of the zone and below.

Umpire Accuracy by Pitch Type

That doesn’t mean that most of those missed calls necessarily go against the knuckleballer, but some strong evidence suggests that it does. The table below lists the called-strike rate on pitches taken in the strike zone from 2008-19, broken down by pitch type. Knuckleballs (which have a middle-of-the-pack called-strike rate on pitches taken outside of the zone) are in a class of their own at the bottom of this list. On average, umps are at their least generous at awarding strikes when knuckleballs are concerned (although Dickey and Wakefield rank fifth and 11th among all pitchers since 1988 in career called strikes above average, a BP metric that quantifies a pitcher’s skill at eking out extra strikes outside the zone, which suggests they may have received more called strikes than expected).

Called-Strike Rate on Pitches Taken in the Strike Zone

Robot umps could gain knuckleballers some strikes, assuming the definition of the strike zone stays the same. And that’s not the only benefit: Catchers would no longer have to try to receive the darting, randomly breaking pitch cleanly. With the bases empty, they wouldn’t have to touch it at all; that Bob Uecker quote about the best way to catch a knuckleball would be more accurate than ever. And while they would still have to keep balls in front of them with runners on base, they could focus completely on blocking balls in the dirt and forget about neatly gloving strikes, which would mean fewer wild pitches, passed balls, and bruises. “I definitely do think the aspect that the catcher doesn’t have to frame it would help,” says Haeger, who knows that the need for a partner who can competently catch the pitch weighs heavy on teams that try out knuckleballers. Martin, who currently keeps an extra-large catcher’s glove with him to hand off to his batterymates, adds that not needing to catch the frustrating pitch would also save overtaxed backstops some psychological strain.

As always, the knuckleball’s fate remains murky, with or without robot umps. Mariners pitching coordinator Max Weiner agrees that technology is aiding its development, but the small number of knuckleball pitchers makes it tougher to come up with the broadly applicable best practices that data-centric teams have used to create breaking ball assembly lines. “There just isn’t the same sample of video, coaching trial and error, and measurables to collect to then convert to coach-speak,” Weiner says. “As coaches, we need continued exposure to bad, average, and elite knuckleballs to continue establishing and improving a baseline teaching method.”

Chris Nowlin, an indy league knuckleballer who runs an instructional company called Knuckleball Nation, argues that the pressure to keep pace with increasing fastball speeds may be further restricting the knuckleball talent pool. Some knuckleballers, including Dickey, Wright, and Jannis, have dialed up their knucklers into the 80s, but that takes arm strength that not every potential knuckleball pitcher possesses. “Now you’ve dwindled the prospective pool of knuckleballers, because the velocity paradigm has shifted,” Nowlin says. “You now need at least 85 mph in your arm, and guys with that type of velocity usually struggle for more velocity to emerge as conventional pitchers rather than spend years frustrated with the knuckleball. And without time, you can’t make a knuckleballer.”

It’s possible, then, that the pitch just can’t keep up in an era when players are getting better by the year. Maybe knuckleballers, with their one weird trick to make the majors, had less room to grow than players with broader skill sets. On the other hand, the contrast between a soft-tossing knuckleballer and a non-knuckleballer could be hard for hitters to handle, especially if a knuckleballer was used as an opener or entered in relief of a fastball beast. “These days, I feel a lot of teams kind of like gimmicks like that,” Martin says. “And especially if somebody really has [a knuckleball], it’s not only a gimmick. It’s a weapon.”

As Nowlin notes, hitters have optimized their attack angles and launch angles to counter conventional pitching, but because no one ever knows where the knuckleball will end up, “no amount of swing-plane analysis could counter it.” He also sees potential for evaluation and replication of the pitch to improve. “Tech can help set quantifiable, undeniable benchmarks similar to the ones used for conventional pitchers,” he says. “The proper tech could track hundreds of thousands of knuckleballs in different conditions to build a model of the perfect knuckleball. And that model would dispel the fear surrounding the pitch.”

Bannister believes that even with high-speed cameras and other data on its side, the knuckleball club will stay exclusive. “Very few pitchers can release a ball consistently with their hand perfectly square to home plate and generating the right amount of very subtle horizontal spin under the pressure of game situations,” he says.

But as the pitch’s practitioners have demonstrated repeatedly, a few is all it takes to stave off extinction. “There’s going to be some more knuckleballers in the big leagues,” Martin says. “And hopefully I’m one of them. But yeah, it’s going to happen.”

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris of Baseball Prospectus, Geehoon Hong of TrackMan, and David Appelman of FanGraphs for research assistance.