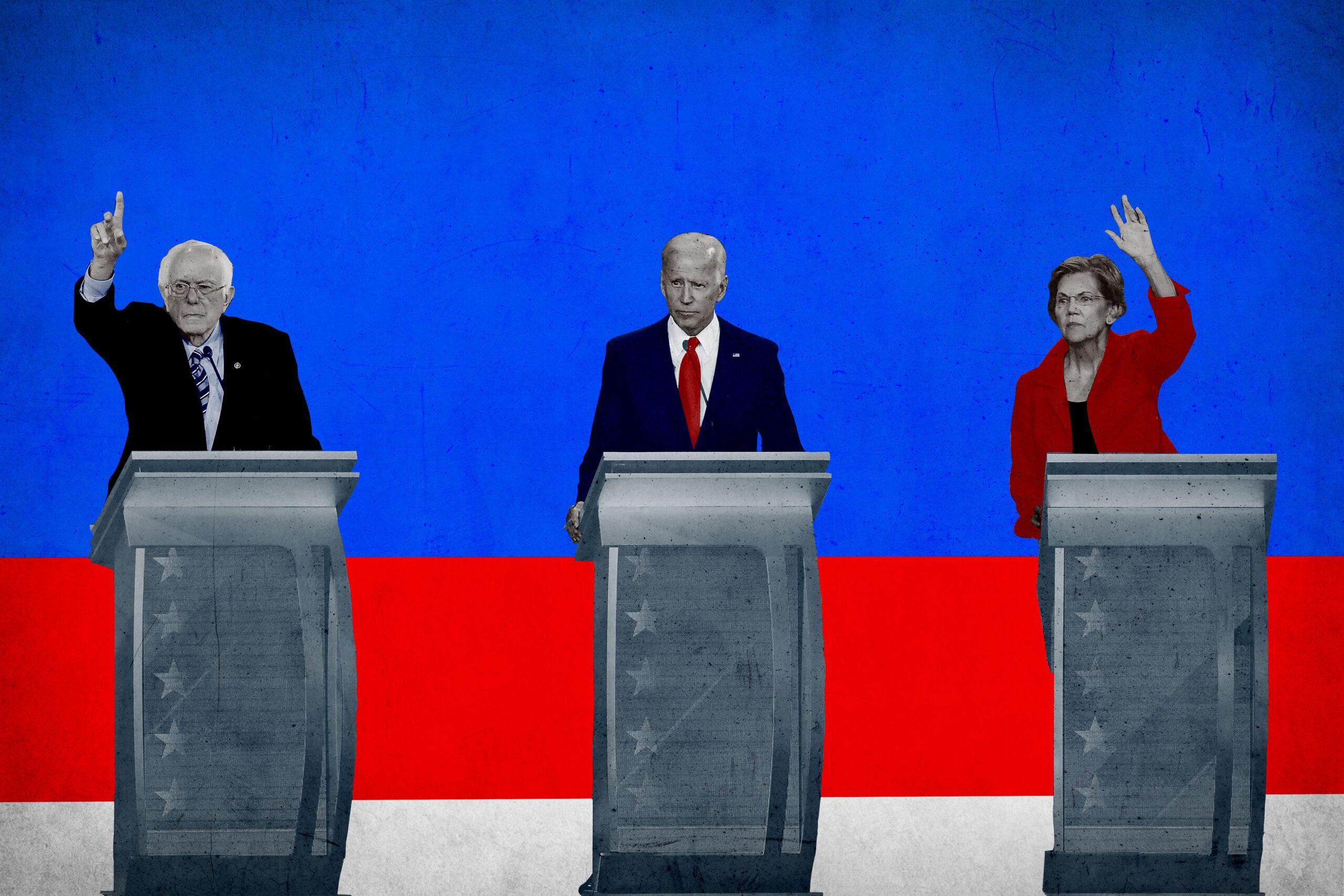

In his opening remarks at the third Democratic presidential primary debate, Joe Biden struck a lonesome defensive in his battle against “Medicare for All.” “My distinguished friend—the senator on my left—has not indicated how she pays for it,” Biden said, “and the senator [on my right] has in fact come forward and said how he’s going to pay for it, but it gets him about halfway there.”

Biden was referring to Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who flanked the former vice president on the debate stage at Texas Southern University in Houston. It was the first debate on network television, and the ABC News moderators asked the 10 candidates far more pointed questions than in the previous debates on CNN and MSNBC. It was also the first time Biden and Warren appeared on the same stage together, which presented a loaded contrast given their decade-old rivalry about bankruptcy reform in the Senate.

But Biden and Warren didn’t duel too aggressively. Biden and Sanders—the two front-runners in the race—haggled over health care reform (in the first hour) and the Iraq War (in the second hour), but they, too, declined to heighten the ideological contrast of their positions. Instead, Biden again confronted his most unlikely critic, Julián Castro, who, like Biden, served in Barack Obama’s administration. Castro, the former secretary of housing and urban development, mocked Biden’s wavering promises about buy-in costs in his “Medicare for choice” proposal. “Are you forgetting already what you said just two minutes ago?”

Castro then ridiculed Biden’s attempt to deflect questions from the Univision anchor, Jorge Ramos, about 3 million deportations—“the most ever in U.S. history,” Castro stressed—recorded under the Obama administration. “Every time something good about Barack Obama comes up, he says, ‘oh, I was there, I was there, I was there, that’s me, too,’ and then every time somebody questions part of the administration that we were both part of, he says, ‘well, that was the president,’” Castro said. “He wants to take credit for Obama’s work but not have to answer to any questions.”

Biden didn’t quite lose to Castro, whose remarks verged on arrogance and cruelty. But Castro’s pointed attacks on Biden’s record as vice president underscored a persistent riddle in these debates. Obama remains highly popular among Democratic voters, and Biden wastes little opportunity to tout that administration’s record. How might the party’s major presidential contenders glamorize Obama’s legacy even as they jockey to supersede the signature achievement of his presidency? On Thursday, the 10 Democrats on stage acknowledged only two partisan forebears: Barack Obama and Bernie Sanders.

Biden’s rivals paid homage to Obama’s efforts to overhaul the health care system. They asserted Obama’s singular responsibility for Obama’s legacy, for better or worse. They denied Biden credit for, well, anything. Meanwhile, they regarded Sanders with measures of deference that elude Biden. “I want to give credit, first, to Barack Obama for really bringing us this far. We would not be here if he hadn’t the courage, the talent, or the will to see us this far,” California Senator Kamala Harris said. At the end of July, Harris withdrew her support for “Medicare for All,” if only to launch her own proposal which would permit private insurance. “I want to give credit to Bernie. Take credit, Bernie! You brought us this far on ‘Medicare for All,’” Harris continued. In these debates, “Medicare for All” has proved as influential in theory as Obamacare has proved in practice. Sanders has proved more vital than Biden in determining what the candidates even bother to discuss. Biden has proved inessential in most policy discussions, though he remains indispensable, in purely practical terms, as a bulwark against Sanders at the polls.

But Biden struggles to deny Sanders’s influence within Obama’s party, a point reinforced by Castro in the debate. “I also want to recognize the work that Bernie has done on this,” he said. “We owe a debt of gratitude to President Barack Obama. Of course, I also worked for President Obama, Vice President Biden, and I know that the problem with your plan is that it leaves 10 million people uncovered.” Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar opened the debate with complaints about “off-track” proposals and partisan extremes; she later formalized her opposition to “Medicare for All.” “I don’t think that’s a bold idea. I think it’s a bad idea,” she said. To bolster her criticisms, Klobuchar needed only turn to the party’s alternative figurehead, Obama, in her push for a public option. “What I favor is something that Barack Obama wanted to do from the very beginning,” Klobuchar stressed. She echoed Biden without ever deigning to defend him.

Biden may be popular among Democratic voters, but he becomes a marginal figure in the company of his Democratic rivals. In a quaint moment for an otherwise slick participant, South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg fretted about Castro’s hostility toward Biden. “This is why presidential debates are becoming unwatchable,” Buttigieg interjected. “This reminds everybody of what they cannot stand about Washington: scoring points against each other, poking at each other.” Castro relished the irony in Buttigieg’s seizing a debate stage to rail against the very existence of disagreement: “It’s an election,” Castro responded. Viewers might have struggled to discern which candidate’s example proved more Obama-esque: Buttigieg’s post-partisan posturing or Castro’s irreverent challenge to a front-runner on the defensive. They might struggle to accept Sanders’s vision for U.S. health care. But Biden offered viewers little reason to believe he might dominate the Democratic imagination as Obama once did—and how Sanders now does.