All Elite Wrestling’s All Out pay-per-view on August 31 was true to the form the upstart promotion has quickly established: lots of flashy high spots and some occasional blood. Thumbtacks glued to a skateboard were embedded in brawler Joey Janela’s back, and veteran Chris Jericho’s apparent “blade job” heightened the drama of his title match with Adam “Hangman” Page. Nothing was as striking as the gruesome crimson mask Dustin Rhodes donned at May’s Double or Nothing pay-per-view, but nevertheless, it was a sign that fans—who are seen screaming for “blood and guts” in an AEW promo video—might be in store for a rougher, tougher product than what’s on offer from WWE, which prohibits “intentional bleeding” in its programming. And, from a historical perspective, there might be some truth to the old wrestling maxim, “Matches have to go red to go green.”

But just how red do matches need to go until green becomes fool’s gold? Vince McMahon—whose WWE used blood and guts to distinguish itself from Turner Broadcasting’s much more buttoned-down World Championship Wrestling during the “Attitude Era” and who has bled in the ring many times himself—has gone on record with his belief that TNT, AEW’s broadcasting partner, won’t put up with “the blood and guts and gory things that they have been doing.” Cody Rhodes himself has acknowledged that “you won’t see that necessarily on a weekly broadcast on TNT,” but has also emphasized how “blood feuds and some of the more graphic content … is more in line with B/R Live and our streaming services and the pay-per-views.” In other words, the son of one of the sport’s best bleeders intends to keep that tradition alive, even if you’ll have to pay for the privilege of witnessing it.

When staged blood first entered the sport of professional wrestling in the early 1900s, it was also all about the money—gambling money. An Arkansas con man named John Maybray led a gang of grifters who traveled through the Midwest, staging wrestling matches and convincing local rubes to bet their savings on the surefire winner of a “rigged” match. By this time, the sport was well on its way to becoming a totally worked, or predetermined, spectacle, so Maybray’s claims probably didn’t require much of a leap of faith on the part of the victims. However, the matches would end prematurely, with the supposed winner biting down on a small bladder full of chicken blood to ensure that he lost via injury stoppage. Before law enforcement could crack down on the operation, several marks had bet and lost the farm, with one unlucky shill plunking down $10,000 on a match.

Maybray’s scam might have been an aberration, but blood wasn’t going anywhere. As the sport began to lean heavily on theatrical, brawling matches between characters during the late 1920s, color—the industry lingo for in-match blood—reemerged as a critical part of the show. Kirby Watkins, who learned how to wrestle in the Navy and wrestled as “Tex” Watkins and “Sailor” Watkins, enlivened his professional matches in the early 1930s by drawing “hardway” blood—the old-fashioned way (or a closer approximation thereof—from his opponents with his teeth, his sharpened fingernails, and even the metal tips of his boot laces. Watkins’s success spawned imitators, most notably Danny McShain, who fought color with color, using both chicken blood capsules and hardway blows to stain the mat red.

Long-time NWA champion Lou Thesz, who relied on wrestling and submission skills to bring the crowds to their feet, deplored the spread of bloodletting in his sport, which quickly evolved past blood bladders and well-timed hardway punches to encompass concealed blades and other sharpened implements. “By the late 1940s, we’d begun to see a handful of boys who regularly used blood in their matches, and they used it for one simple reason: they couldn’t do anything else,” he wrote in his autobiography. “It was the cheapest way of attracting attention, but it worked, and it was a way for them to stay employed.”

Plenty of wrestlers, even talented ones like Mark Lewin, used blood and guts to extend their careers indefinitely. Lewin, who wrestled as a clean-cut, muscular, babyface adversary of Detroit’s bloodthirsty Sheik and then, much later, as a villainous “Purple Haze” ally of cult leader Kevin Sullivan in Florida, recognized that color at the right time could cause territories to explode. In San Francisco during the 1950s, he kneed Mike Sharpe in the face and Sharpe began to bleed. “There was no blood in San Francisco at the time, so that was the first thing people saw, and business just shot up,” he noted in The Multiple Personalities of Mark Lewin. When faced with a depressed market for wrestling in Australia in the 1960s, he went back to the well: “Mitsu Arakawa Pearl Harbored me [during a TV taping in Brisbane], and when he ran me into the turn post with a wire sticking out I was cut wide open. Blood streamed down my face, and it was quite an injury. Based on that, Mitsu and I sold out Australia coast to coast, and we brought business from zero to capacity.”

Don Fargo, who began his career as Don Kalt from Pittsburgh before teaming up with southern legend Jackie Fargo to headline as the “Fabulous Fargos,” loved getting color because it always meant a little extra money in the pay envelope. “If I was running short when the rent came due, I could do hardways and make my rent money in a few nights, and the extra cash allowed me to buy more rifles and pistols,” he wrote. “I’d go to the promoter and say, ‘Listen, I don’t like to use a blade because some of the fans are wise to it and I don’t want ’em to think that’s what I’m doin’. For an extra 25, I’ll let ’em bust my eye open.’”

Blading—using a carefully constructed and concealed piece of razor to cut open oneself mid-match—was nonetheless the preferred method for all the grapplers who roamed the territories and sliced themselves open to increase gates or conclude story lines. Bugsy McGraw, who played both a hulking heel and a man-child babyface during a three-decade career that spanned wrestling’s territorial era, relied on the most conventional method for concealing his blades. “I usually opted to put the blade in a flap of tape on my finger,” he explained in his autobiography when describing how he prepared for the blowoff to “brass knuckles” matches and other gory showdowns. “To keep fans from getting wise to the presence of blades, I would commonly tape up four or five fingers so they wouldn’t know where to look.” He wouldn’t keep the blade in his mouth like some others recommended, though. “If you mishandle a strip of a razor blade in your mouth, all sorts of horrible things could happen … if you swallowed the blade, that could be a nightmare.” And, as Jim Cornette added in his own shoot interview about blading during this period, if a wrestler dropped a blade and fans happened to see it, that unlucky wrestler and many others in the promotion would probably wind up getting busted open hardway until credibility was restored.

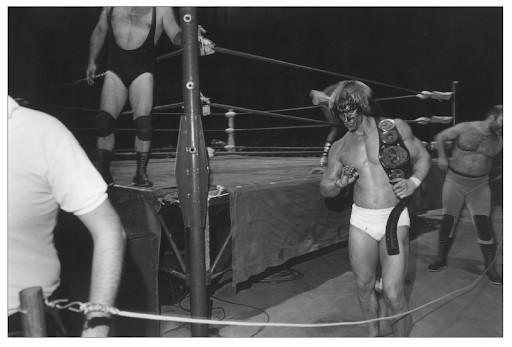

It was in the shadows of performers like Lewin, Fargo, and McGraw that major stars of the 1980s, such as perennial NWA champ Ric Flair and Cody Rhodes’s father Dusty, perfected their craft. Rhodes’s bloody face, as seen in legendary slugfests with “Superstar” Billy Graham and Harley Race, graced dozens if not hundreds of wrestling magazine covers. Flair, who wrestled (and bladed) well into his 60s, has forehead tissue so brittle it would turn into a bloody mess even in minor kerfuffles. And those two wrestlers clearly had a major influence on Cody’s approach to in-ring bloodletting as an essential storytelling device.

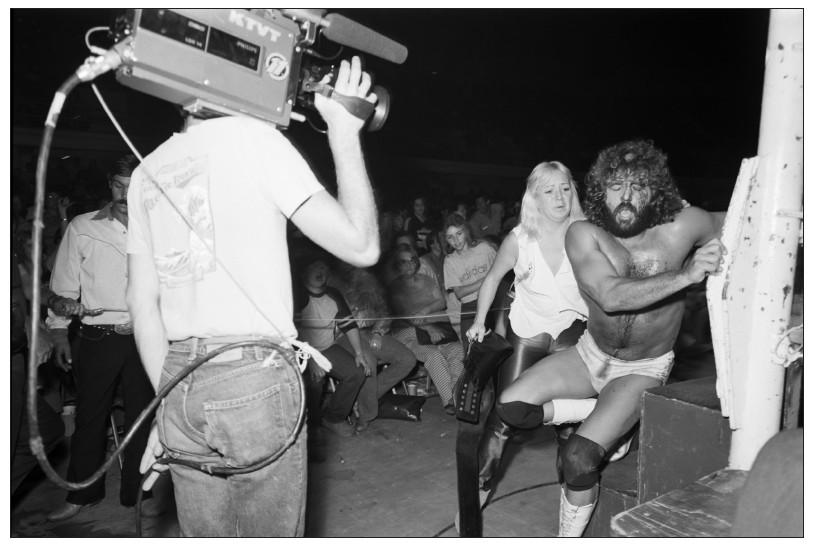

But even during my childhood, blading was on the wane. Eddie Mansfield and ex-NFL player Jim Wilson, minor figures in the wrestling business, exposed the craft of blading to John Stossel in the same 1984 20/20 segment in which David Schultz slapped Stossel to the ground. Mansfield even bladed on television, drawing a thin line across his face—a rather shocking moment in retrospect as far as 1980s television programming goes. And even though the WWF product would see some notable blade jobs during this time, such as King Kong Bundy at WrestleMania 2, the increasingly family-friendly promotion eventually put a stop to intentional blading until fierce competition from WCW in the 1990s forced a reversal.

WCW, too, had tried to stamp out the practice of intentional bleeding, which had been a hallmark of the Charlotte-based Jim Crockett Promotions operation it had acquired in 1988. At the time of the sale, the roster was laden with veterans of the southern circuit, notorious bleeders such as Flair, Rhodes, Ivan Koloff, “Mad Dog” Buzz Sawyer, and Kevin Sullivan. Dusty’s son Dustin, who occupied a prominent role in the early 1990s WCW, wound up getting cut from the promotion for deliberately bleeding in a match against Barry Darsow, then working as the “Black Top Bully.” “It was in the script and I actually questioned whether or not we could do it on the bus ride to a shoot,” he wrote in his autobiography, Cross Rhodes. “I told the head producer, ‘For whatever reason, WCW boss Eric Bischoff doesn’t want us to blade. We need to get this approved from up above.’ I didn’t want to blade because I knew the consequences. I didn’t have a problem with blading. I just didn’t want to get fired for it.” (It was that firing, of course, that led Rhodes to WWF and the Goldust character with which he achieved his greatest success.)

In Controversy Creates Cash, Bischoff, who was working as WCW’s executive producer, expressed a distaste for intentional blading. “Turner Broadcasting then tried to tell us that under no circumstances—even if it was an accident—were we to show blood. I thought that was stupid and overreacting, and wrote my own policy,” he wrote. “Personally, I was never a big fan of blood. Blood isn’t something that makes people enjoy the product more. I think if occasionally it happens in the course of a match by accident, it happens. You show it. But if the match has so little drama that you’re forced to cut your head open, you probably messed up earlier on.”

But like it or not, blood would come back in a big way in the late 1990s—partly to combat the success of Bischoff’s WCW, which was doing well in the ratings but hamstrung by certain restrictions (like bloodletting) in place on both TNT and TBS. The resurgent WWF managed to eke some fantastic dramatic moments out of blade jobs, like when a smashed-up “Stone Cold” Steve Austin passed out in Bret Hart’s sharpshooter submission at 1997’s WrestleMania 13 pay-per-view. And Paul Heyman’s Extreme Championship Wrestling, always underfunded and forced to make something out of nothing, managed to win the affections of wrestling insiders and a small core of fanatically loyal fans with dangerous stunts and gashed-up foreheads. In Japan, hardcore legend Atsushi Onita’s Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling association brought “garbage wrestling” back to the forefront there, managing to compete with New Japan Pro-Wrestling and All Japan Pro Wrestling by treating fans to matches featuring barbed wire and explosions.

But there were numerous dangers that accompanied this type of slash-and-burn production. Kevin Sullivan—no stranger to blade jobs, which dated back to his time with “Purple Haze” Mark Lewin in Florida— treated Smoky Mountain Wrestling fans to a ghoulish and perhaps pointless bloodletting in 1993, when he drove scissors into the arm of future Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling fixture Kintaro Kanemura—which Jim Cornette’s promotion “censored” by placing a big red X across the screen, partially obscuring the carnage.

Kanemura would live to endure many more similarly gory bouts, but 17-year-old Erich Kulas suffered far more significant injuries when he appeared on an ECW house show as a fill-in for D-Von Dudley’s tag team partner Axl Rotten in a match against New Jack and Mustafa Saed. ECW veteran the Blue Meanie, speaking in a shoot interview recorded in 2018, said that Kulas showed up with two midget wrestlers in tow, claiming to have been trained by Killer Kowalski (who was usually at ECW events with his wrestling students, but was absent that night) and billing himself as a Ralph Kramden–esque bus driver character whom Paul Heyman hurriedly christened “Mass Transit.” While in the ring with New Jack, Kulas apparently asked to be bladed, and the result was New Jack carving a massive gash into Kulas’s forehead with a surgical scalpel, severing two arteries in the process. Video of the incident was captured on camcorder; New Jack seized the moment to get some heat by telling the crowd he didn’t care whether Kulas died, and Kulas’s father exclaimed that his injured son was only 17. The incident recalled a similarly horrifying hatchet job in the 1970s, when a past-his-prime “Doctor” Jerry Graham sent enhancement talent Emmanuel Beach to the hospital for 70 stitches after carving into Beach’s head with a scalpel during a lower-card match in Detroit. (Prior to the bloodletting, Graham had asked a ringside photographer whether he would be using color film that night.)

The most notable cautionary tale of blood and money, however, is that of Abdullah the Butcher. Born Lawrence Shreve in Ontario, Canada, he rebranded himself as a “Sudanese” version of Detroit’s violent Sheik. Although he incorporated some judo throws and other martial arts moves into his repertoire, over the course of his career, Abdullah got heavier and heavier and did less and less—he showed up, scraped his forehead or the forehead of an opponent like Hulk Hogan or Bruiser Brody, and then made some faces at the crowd until the match went to a double disqualification. Abdullah understood his unique appeal, telling an interviewer that the deep ridges in his head were reminders of past paydays. But he also presented a unique kind of danger, with “Superstar” Billy Graham going on the record to accuse his former opponent of criminal assault, calling him a “bloodthirsty animal.” Canadian wrestler and YouTube channel operator Devon “Hannibal” Nicholson was infected with Hepatitis C during a 2007 match against Abdullah, for which Nicholson sued and won a $2.3 million judgment in a Canadian court that was later ruled enforceable in Georgia, where 78-year-old Abdullah currently resides.

Regardless of the direction AEW takes, it seems unlikely to become a latter-day version of Atsuhi Onita’s FMW or home to “garbage” wrestlers such as Abdullah the Butcher and more recent hardcore stars such as the now-retired Necro Butcher. After all, AEW has already taken steps to regulate the use of chair shots. Meanwhile, the WWE isn’t totally averse to using blood effects, such as when Roman Reigns appeared to use a blood capsule on a 2016 episode of RAW or when Brock Lesnar bloodied Reigns the “hard way” in the main event of 2018’s WrestleMania 34. Should the competition between WWE and AEW heat up in the coming months, it’s possible that either company could turn to additional “red” to rake in more “green.” Cody Rhodes and Vince McMahon are both third-generation members of the wrestling business, and if history has taught us viewers anything, it’s that promoters will put anything on the line for views and engagement, even their own flesh and blood.