The Unexplainable, Undeniably Entertaining Rituals of the Bills Mafia

The Buffalo teams of the past two decades have lost a lot of games, but have spawned a dedicated group of partisans who drink alcohol out of bowling balls, jump through tables, and spray ketchup on each other. To some, these traditions are deeply weird. To this fan base, they’re the ties that bind.As characters go, Pinto Ron is a big one. He’s certainly the most famous member of the Bills Mafia. That’s what Buffalo Bills fans call themselves. Pinto Ron isn’t his real name, nor is it his only identifier. His given name is Ken Johnson, and he’s Kenny to his friends—which everyone who attends his Bills tailgates inevitably ends up being.

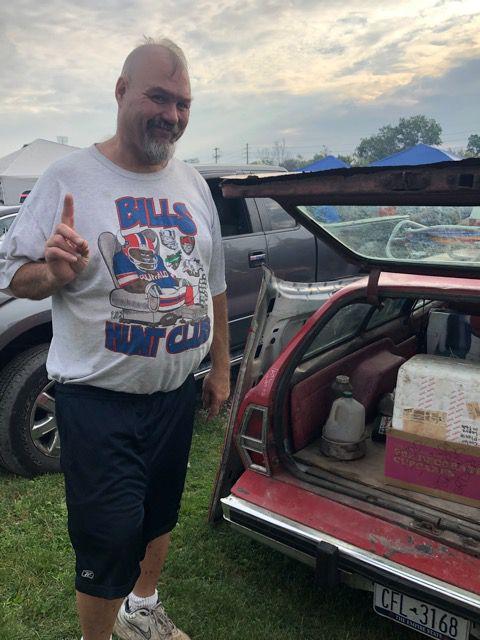

Johnson is a small man with a bushy, white Papa Smurf beard. He’s been tailgating for 31 years. Hasn’t missed a Bills game, home or away, since 1994. Last Sunday’s home opener, a 21-17 win over the Bengals that pushed Buffalo’s record to 3-0, was his 409th straight game. “If I make it inside,” Johnson told me before kickoff around 8:30 a.m. “I’m old. Old people die all the time. I don’t want to be presumptuous.”

Johnson’s tailgate, tucked into the back of a private parking lot in the shadow of New Era Field outside of Buffalo, New York, has been a must-see attraction for decades. He told me it has several “calling cards.” One involves offering shots of 100-proof wisniowka liqueur out of a hole in a bowling ball. There’s a ritual to it. Do the shot, drop the bowling ball, and then blow into a vuvuzela for unknown reasons. The shots are free for anyone who wants to risk temporary blindness, and yet the line to take one never ends. One first-timer described the experience as “awful—like drinking rubbing alcohol.” I saw him back in line about half an hour later.

People also know Johnson for his beat-up, rusty red Ford Pinto that serves as a tailgate totem—hence the nickname Pinto Ron and the accompanying @PintoTailgate Twitter handle—and doubles as a … let’s just call it a unique food preparation and production area. Johnson’s friends fire up all sorts of items in, on, and around the Pinto by employing some … let’s just call them unorthodox conduction methods. An army helmet is used to cook chicken wings. A shovel heats omelets and pancakes. A saw blade fries up bacon. A toolbox grills burgers and dogs. A hub cap is a makeshift wok for stir fry. And my favorite: a filing cabinet bakes pizza. I have no idea what the heat sources are. The net effect feels like a deleted scene from a spinoff of Mad Max.

Like the shots, the food is free. But as with the bowling ball, eating from the communal buffet requires giving up any pretense of sanitation. A guy named Todd was standing next to me when one of Pinto Ron’s helpers wandered by with the last couple of mini franks on a paint tray. Todd thanked him, then dipped the tiny tubes of meat into a reservoir of greasy white condiment that might have been ranch or bleu cheese or maybe liquid botulism. “Delicious,” Todd said with a smile. “I wonder how many diseases I just got.”

Scenes like this may seem at home at countless NFL tailgates across the country, but Bills Mafia takes things further than most. If it feels like their antics have grown progressively more outrageous over the years, that’s because they have. The Bills Mafia has come to define the team’s entire fan base. At some point during the last decade, the wildest and (likely) most overserved Bills fans started gaining attention for throwing each other through folding tables, like professional wrestlers without the formal training. Just last Sunday, a viral video captured a Bills fan (mis)using fireworks to disastrous effect; the accompanying comments were as empathetic as you might expect.

These days—more than the filing cabinet pizzas or bowling balls full of booze—Pinto Ron is best known for getting doused in ketchup and mustard before each game. It’s become such a spectacle that crowds assemble about an hour and a half before kickoff in anticipation. Johnson stands there, the mob around him chants, and then people climb atop a nearby van and drench him in red and yellow condiments. Everyone loves it. Everyone except Kenny, maybe.

Kenny said that the ceremony has really taken off because of social media. When I ask whether there are times when he doesn’t feel like getting covered in ketchup and mustard, when maybe he just wants to eat some army helmet wings or a shovel omelet and watch his beloved Bills in peace, he doesn’t hesitate. “Yes. Every one of them,” he said. “I can’t get out of it.”

Such are the responsibilities of fame. Such, too, are the ties that bind a football city that has had little to celebrate since the turn of the century. In the run-up to Sunday’s home opener, I met a guy dressed in a full buffalo costume; a man calling himself “Shorty McBill” who rocked a red, white, and blue leprechaun tuxedo getup with tails; and several people dressed as ketchup or mustard bottles—all of whom were well lubricated by midmorning. Bills fans don’t just like to get weird, they lean into it.

Such are the responsibilities of fame. Such, too, are the ties that bind a football city that has had little to celebrate since the turn of the century. In the run-up to Sunday’s home opener, I met a guy dressed in a full buffalo costume; a man calling himself “Shorty McBill” who rocked a red, white, and blue leprechaun tuxedo getup with tails; and several people dressed as ketchup or mustard bottles—all of whom were well lubricated by midmorning. Bills fans don’t just like to get weird, they lean into it.

When Buffalo hosts the similarly undefeated Patriots this weekend, the Bills will have a chance to take control of a division that New England has dominated for decades. Perhaps just as important to the fans, Bills Mafia will have another opportunity to showcase its curious customs, which have become equal parts regional identity and rallying cry. There are lots of oddball fan bases around the NFL. Oakland and Philly come to mind. But considering how bad the Bills have been in the years following their four straight Super Bowl losses in the 1990s, why has this one remained so intensely loyal? And how did it get so deeply strange? Crucially, why was former Buffalo wide receiver Stevie Johnson hanging out with Bills Mafia before last week’s game—practically shirtless, no less—ready to drench his good buddy Pinto Ron in ketchup?

It’s odd. The whole tailgate scene, obviously, but also the continued fondness for a team that hasn’t inspired any real reason for affection in decades. Nostalgia plays a part—both for those who actually experienced Marv Levy’s hard-luck, sad-sack, would-be paper champs of the early ’90s and those who have only heard the what-if stories. But the years since then have been lean enough that any objective consumers would wonder about the nearly nonexistent return on their substantial comparative emotional and financial investments. At the very least, apathy should have long since set in, rendering Buffalo a northern facsimile of Jacksonville or Miami or wherever it is that the Chargers play. It feels like someone should have called bullshit by now.

The Bills haven’t won double-digit games in a season in 20 years. During that stretch, they’ve lost double-digit games nine times, including five seasons in a row from 2009 to 2013. Dating back to 2000, they’ve employed 10 different head coaches—one of whom infamously up and left the team for a job as the Jaguars offensive line coach—and had 25 quarterbacks throw at least one regular-season pass. The list of signal-calling luminaries includes such names as Alex Van Pelt, J.P. Losman, and everyone’s favorite would-be (but wasn’t) robo QB Rob Johnson.

There has been heartbreak after heartbreak. There was the Music City Miracle. The Week 17 loss to the Steelers backups that kept Buffalo out of the playoffs. The Monday Night Football collapse against the Cowboys. The impossible Patriots comeback in Terrell Owens’s Bills debut. Things got bad enough that the franchise’s former ownership group started playing a handful of “home” games north of the border in a naked cash grab called the Bills Toronto Series. Through it all, there’s been unceasing speculation that the team might relocate—this summer, league commissioner Roger Goodell not so subtly said that the Bills need to replace their 45-year-old stadium for “stability”—though the new ownership group insists that the team is staying in Buffalo. It seems like the only recent constants for the Bills have been organizational dysfunction and a fan base that won’t quit the team no matter how many reasons it gives them.

Del Reid has lived through it all. He still thinks about the big debate—Doug Flutie or Rob Johnson. He was and remains a Flutie man, which was the only right answer then and now. If Buffalo is ground zero for Zubaz pants—they’re as ubiquitous around the stadium as cans of Molson—then Reid is patient zero for the Bills Mafia. Reid, 43, was born and raised in Buffalo. He’s a lifelong Bills fan. And he still finds his part in the origin of the term “Bills Mafia” somewhat hard to believe.

In a November 2010 matchup against the Steelers, then–Bills receiver Stevie Johnson dropped a potential game-winning pass. He was broken up about it, and fired off a tweet that included many capital letters and exclamation points and seemed to blame God for his error. A media shitstorm ensued. Johnson was the subject of conversations on The View. The New York tabloids feasted on him. So did Stephen Colbert, who lampooned him with glee. ESPN’s Adam Schefter was late to the conversation and didn’t retweet Johnson’s remarks until the next evening, which prompted Bills Twitter to bust his balls with the hashtag #SchefterBreakingNews. Schefter promptly blocked several of the perceived offenders. Weeks later, on a Follow Friday (yes, that used to be a thing), Reid tweeted out the handles of those who were blocked with the hashtag #BillsMafia, since they fancied themselves the black hat antiheroes of the saga.

When former Bills linebacker Nick Barnett signed with the team, he picked up on the Bills Mafia moniker. Eventually, running back Fred Jackson did the same. So did franchise legend Andre Reed. Before long, even the Bills official team account was using #BillsMafia in tweets. Go to a Buffalo tailgate now, and Bills Mafia flags and T-shirts are everywhere you look.

Reid was floored. “It happened so organically,” he said. “I never had a plan for how it would play out.” He did recognize an opportunity, though. He started BillsMafia.com—a fan blog with posts written by many of the people Schefter blocked on Twitter—and eventually launched an apparel company called 26 Shirts after he lost his gig as a web developer.

The Bills Mafia phenomenon has since grown well beyond his control. As Reid admits, “If you love the team, you’re part of it.” Everyone has adopted the phrase—including and especially the table-smashing crowd. That’s not Reid’s bag. Over the course of several conversations, I got the sense that Dr. Frankenstein would prefer that the monsters who gained notoriety in part because of his branding would behave themselves. Reid said the most raucous subset of the fan base existed long before he dreamed up the name Bills Mafia, and emphasized that he deserves “no credit or fault for a lot of these shenanigans.” As he put it, now “they just have something to yell before they jump through things.”

Being a Bills fan is tough. We don’t have much. We have this.Hans Steiniger

Not every member of the Bills Mafia fits this description, just as “not everyone from Philadelphia hates Santa Claus,” Reid explained in terms I could understand and appreciate. In fact, most of the parking lots outside Bills games have banned table smashing and dizzy-bat races, another favorite fan activity, as part of the team’s recent edict that “our number one concern as an organization is fan safety.” There were reasons to worry. As recently as 2012, there were nearly 100 ejections and close to 30 arrests at one Buffalo game alone, and two people died that same day.

But Bills fans have also done things that haven’t gotten nearly as much attention as the rowdy mischief. In 2018, when the Bengals beat the Ravens to push the Bills into the playoffs for the first time in nearly two decades, Bills fans raised almost $300,000 for Andy Dalton’s charity, which benefits sick children, as a thank you. Dalton and his wife, Jordan, thanked them right back. Later that same year, after NBCSports Chicago called the Bills Mafia “the laughingstock of the NFL,” Bills fans responded by raising thousands of dollars for a pediatric cancer center in Chicago. And after Ezra Castro, better known by his superfan alter ego Pancho Billa, died of cancer in May, Bills fans rallied to donate more than $100,000 in his name to Teacher’s Desk, a nonprofit that provides backpacks and school supplies to students in need. Bills Mafia also released doves at a memorial tailgate for Pancho Billa last weekend, while the Bills honored him in a pregame ceremony before kickoff against the Bengals.

“A lot of cool things have happened that are good under Bills Mafia,” said Reid, who donates a portion of the proceeds from 26 Shirts to various charities. He likes to focus on the community component to Bills Mafia. He thinks that’s helped keep the fan base together through all those forgettable seasons.

“Being a Bills fan is tough,” Hans Steiniger told me while Pinto Ron prepared for the ketchup ceremony and the crowd packed in tight around us. Steiniger is the creator of the “Tailgating Hall of Fame” and, like virtually everyone else I met outside New Era Field, a lifelong Bills fan. “This helps. It’s a distraction. When I think about it, a lot of the best tailgates have popped up around bad teams. Cincy. Cleveland. Chicago.”

After surveying the scene, he added another thought: “We don’t have much. We have this.”

Brandon Schultze flew in from Atlanta for the home opener. He met up with his cousin, Carl Schultze, who came up from Virginia, and their “honorary cousin,” Fran Simmons, who lives in upstate New York. They’re all 20-something hardcore Bills fans. I met them right after Brandon got done sucking high-octane booze out of Pinto Ron’s bowling ball. They insisted I make the rounds with them so proper introductions could be made. When Simmons asked his friends who they thought I should meet first, Carl immediately pointed and said “That guy. The meatball guy.”

Why?

“He makes meatballs in a bed pan.”

Of course he does.

Of course he does.

And thus began a chain reaction of increasingly bizarre interactions. The meatball-bed-pan guy calls himself Captain Buffalo. He wears a DIY Bills superhero outfit complete with red, white, and blue tights; face paint; and a big, fuzzy buffalo hat with horns. It takes him about an hour and a half to get into character. When I asked his age, he replied “old enough” and explained that he’s been a Bills fan since the Jim Kelly era. Relatively speaking, those must have been good times. “Yeah,” Captain Buffalo said, “until the last game of the year.”

The meatball-bed-pan operation has long been housed just a few feet from Pinto Ron’s setup. Opening weekend, Captain Buffalo explained, is “like a reunion.” When he realized I had not yet met many of his Bills Mafia brethren or been clued into their eccentric customs, he took me to meet Scott Siegel, whom everyone calls Scotty. He has a mostly bald head with a wispy mohawk on top and a big beer belly that he proudly put on full display while walking around shirtless. Later that morning, he painted each side of his head white with the Bills logo layered on top in red—like a human helmet. Everyone agreed he looked great.

As soon as I met Scotty, he asked whether I knew about the famous gallon of milk. It is the stuff of Bills Mafia lore. I told him I did not. And so he dragged me over to the back of Pinto Ron’s Pinto, where he showed me what was left from a gallon of milk he had the day the Bills staged the biggest playoff comeback in NFL history in a win over the Oilers. That was in 1993. What remains does not look like milk, and there certainly isn’t a gallon of it. It’s a brownish liquid. That’s the color Scotty says it changed into over the years because of “chemistry.” There’s maybe a quarter of a gallon left. Siegel said that’s because whatever is in there is now so acidic, it keeps eating through its plastic jug. The gallon container the liquid resides in is not original. Only the liquid is. The plastic container sits inside a metal pan and, when the nightmare fluid eats through a plastic gallon, they just pour it from the metal container into a new gallon and repeat. This process has been going on for 26 years.

You might wonder why Scotty brought a gallon of milk to the game in the first place. He found it in his fridge the morning of that fateful game. It was expired. He figured he’d bring it with him rather than throw it out. He put it in the back of Pinto Ron’s Pinto—then the Bills won and it became lucky, and it’s been in the back of the car ever since. The Pinto also has a jar of lucky leftover pickles sitting in the trunk from a different comeback. (The back of that car is like the Bills fan equivalent of the Mutter Museum.) Scotty thought it was from a win over the Colts, but honestly he couldn’t remember.

From there, I was introduced to Pizza Pete (he made the filing cabinet pizzas and wore a hat stamped with the words “Canada is already great”; both were big hits with the crowd) and the Professor, who was busy cooking burgers and hot dogs on the toolbox grill perched on the hood of the Pinto. The Professor’s real name is Mark Shephard. He runs a research center and teaches engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. He is a man of few words, so I looked him up and found this in his RPI bio:

His research activities have led to well recognized and applied contributions in the areas of automatic mesh generation of CAD geometry, automated and adaptive analysis methods, and parallel adaptive simulation technologies.

He’s smart.

Afterward, I met Leslie Wille, an original Bills Mafia member along with Del Reid. She stood close to Lexi McNeal, who was dressed as a ketchup bottle. Her friend, Brandon Dick, was outfitted as her mustard sidekick. McNeal explained that she is actually “Little Ketchup.” Her dad has been known as “Big Ketchup” since about 1995. She’s only been doing this since around 2001. Pinto Ron is her godfather. The org chart for their operation is dizzying.

While trying to wrap my head around it, I ran into Colin Dee, a regular at Pinto Ron’s party. He was there with his dad, Ron Dee, and his college buddy, Brian Bantel, who was one of the few Bengals fans on hand. (When I asked Bantel whether there’s a Bengals fan analog for keeping rancid milk as lucky charm, he said, “absolutely not” and belly laughed.) The younger Dee appeared twice in a Bills Mafia documentary and did his best to explain to me how this disparate group of individuals fits together. He admitted Bills Mafia is an odd collection of humans—then demanded I take a bite of his half-eaten pulled pork sandwich, which he had just been handed by Pizza Pete, who cooked the meat in an old oil pan from a 1989 Buick. It was good and I have not yet contracted tetanus.

Look, Dee said, what families aren’t strange? They call themselves the Bills Mafia, he continued—and what’s a mafia if not “a dysfunctional family”?

The ketchup ceremony. There’s a whole backstory to that, too, but all you really need to know is how it works: Kenny Johnson holds out a toolbox burger and the crowd chants for ketchup the way you might imagine Romans once chanted for bloodshed. It is wild and weird, even by the high standards the Bills Mafia sets on those fronts. It is also baffling and gross, but man, they really dig it. So at 11:30 a.m. on Sunday, I positioned myself near the corner of Pinto Ron’s van, next to Pizza Pete and Little Ketchup and the Professor and all my new friends and got my phone ready to record in what Dee referred to as “the splash zone.”

The crowd was so deep in every direction it was impossible to tell where it ended or began. Before long, Stevie Johnson emerged and pushed his way through the masses, led by the owner of the aptly named Hammer Lot where all this takes place. Johnson was wearing black jeans, black Vans, and a tank top cut so short that it was functionally closer to a bib. The crowd lost its shit at the sight of him. It’s hard to imagine Bills fans loving anyone more than Stevie, perhaps because he loves them right back and throws himself headfirst into their peculiar rituals. Later, he would gush to me about how much he loves Buffalo and how he can’t understand why more people don’t feel the same way. He told me that NFL players who don’t want to come here are missing out because, well, just look around: Where else can you find such energy and enthusiasm? But first he climbed on top of the van and grabbed a big plastic bottle of off-brand ketchup and gave the people what they demanded.

Dee was right about “the splash zone.” Between Johnson’s zeal and the wind, I caught quite a bit of collateral ketchup and mustard shrapnel. I fought on. When Johnson climbed down off the van, he told me it was “a one-of-a-kind experience” and stopped to take pictures with Pinto Ron, whom he called “a great guy, a great fan.” There they were, two Johnsons from different generations and backgrounds, one covered head to feet in condiments, the other a handsome former professional athlete, both with their arms draped around each other and the same wide, silly grins on their face. It was hard to tell who was having a better time.

As people pressed in around them to snap photos of the two fan favorites, I ran into Dee, who was holding several opened and unopened beers. He nodded at me and raised an eyebrow, a look of acknowledgment that seemed to signal that I had seen something meaningful and must surely get it now. Then something dawned on him. “Oh shit,” he said to Bantel, who was also holding several beers, both opened and unopened, some of which were stuffed into the pockets of his cargo shorts, “there’s a football game after this, too.”