How ‘Almost Famous’ Foretold the Future of Music Journalism

Cameron Crowe’s movie based on his experiences as a Rolling Stone scribe is now a musical—but the stage adaptation comes at a strange time for a struggling industryAlmost Famous is Cameron Crowe’s affectionate, semi-autobiographical account of his supernaturally charmed entrée into the world of music journalism, yet the box office at San Diego’s Old Globe theater makes it sound like a dystopic thriller—“Led Zeppelin is king. Richard Nixon is president,” all of it read in the classic “in a world” inflection by the voice-over on the hold line. But consider what actually happens at the outset for William Miller, Crowe’s 15-year-old stand-in: a budding relationship with Lester Bangs—the world’s “greatest music critic” who just so happens to live in the same cultural dead zone of San Diego ca. 1973—leads to Rolling Stone reaching out to him for a plum assignment. Editor Ben Fong-Torres grants Miller an extra 2,000 words to ensure the maximum amount of face time with a band that offers full access to their backstage high jinks, while promising painstaking oversight and fact-checking. Fong-Torres initially offers Miller $700, and by the end of the phone call, he’s negotiated against himself to up the price to $1,000. To the modern music writer, Almost Famous is essentially science fiction.

For starters: I can virtually guarantee you that much of the freelance music writing you’re reading on the internet will not have earned its author $1,000, let alone the $5,778.33 that Miller’s windfall amounts to in 2019 dollars. Hell, most reviews might net just enough to afford the worst seat in the house to see Almost Famous: The Musical during its pre-Broadway run in San Diego: I’m sitting in CC19, a somewhat visually obscured spot in the far upper-left balcony, and it costs $125.

I can’t recall whether music writers took issue with the accuracy or relevancy of Almost Famous when it was released in 2000, but I imagine they might’ve seen 1973 as “the good ol’ days” before everything got corporate. Sure, file-sharing and streaming had yet to fully decimate the music industry and print journalism was thriving in all genres, but publications had to play nice with teen pop, nu-metal, rap-rock, pop-punk, and Southern hip-hop, all modes of music that critics could casually disregard or outright mock in the past. Meanwhile, Almost Famous: The Musical premiered during the most brutal stretch in a year when “profoundly demoralizing” is the baseline for music journalism.

Just about every major outlet focused on music was hit by significant layoffs in the past several months: Long-tenured contributors were axed at Stereogum and Vibe; Vice’s music vertical Noisey was folded into the main site; I’m not even sure what’s left of Spin at this point; and Conde Nast 86’d Pitchfork’s entire video staff, an ironic footnote in the “pivot to video” boondoggle as well as a greater commentary on the precarity of media unions. That’s all just kindling in journalism’s bigger dumpster fire—whether it’s your local alt-weekly, or a fiercely beloved digital imprint like Splinter or Deadspin, or a venerated legacy figure like Sports Illustrated, nothing is safe from private equity stripping it to the chassis and rebuilding as a content generator. These are the more high-profile of the estimated 7,200 journalism jobs lost thus far in 2019; both Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have deemed this a crisis worthy of their presidential platforms. In the past couple of years, there have been heartfelt and humorous calls for music journalism to return to the days of Tumblr or Blogspot. This might be the only future left if no one’s willing to pay anyone to write about music.

And so the obvious joke is to give Almost Famous the same kind of gritty reboot to which so many pieces of existing IP are subjected: William Miller is now a 22-year-old NYU grad with $100,000 of student loans, pumping out three news posts a day for BuzzFeed when one goes viral … before he can delete all of his problematic Chief Keef tweets from college. Stillwater is a synth-y duo named STLLWTR trying to defy their reputation as industry plants. The “elder statesman” voice of Lester Bangs is now some variant of Robert Christgau pumping out reviews in the netherlands of Vice well into his 70s or a bitter lifer going on long tangents about the insanity of a culture that favors Tame Impala over Iceage.

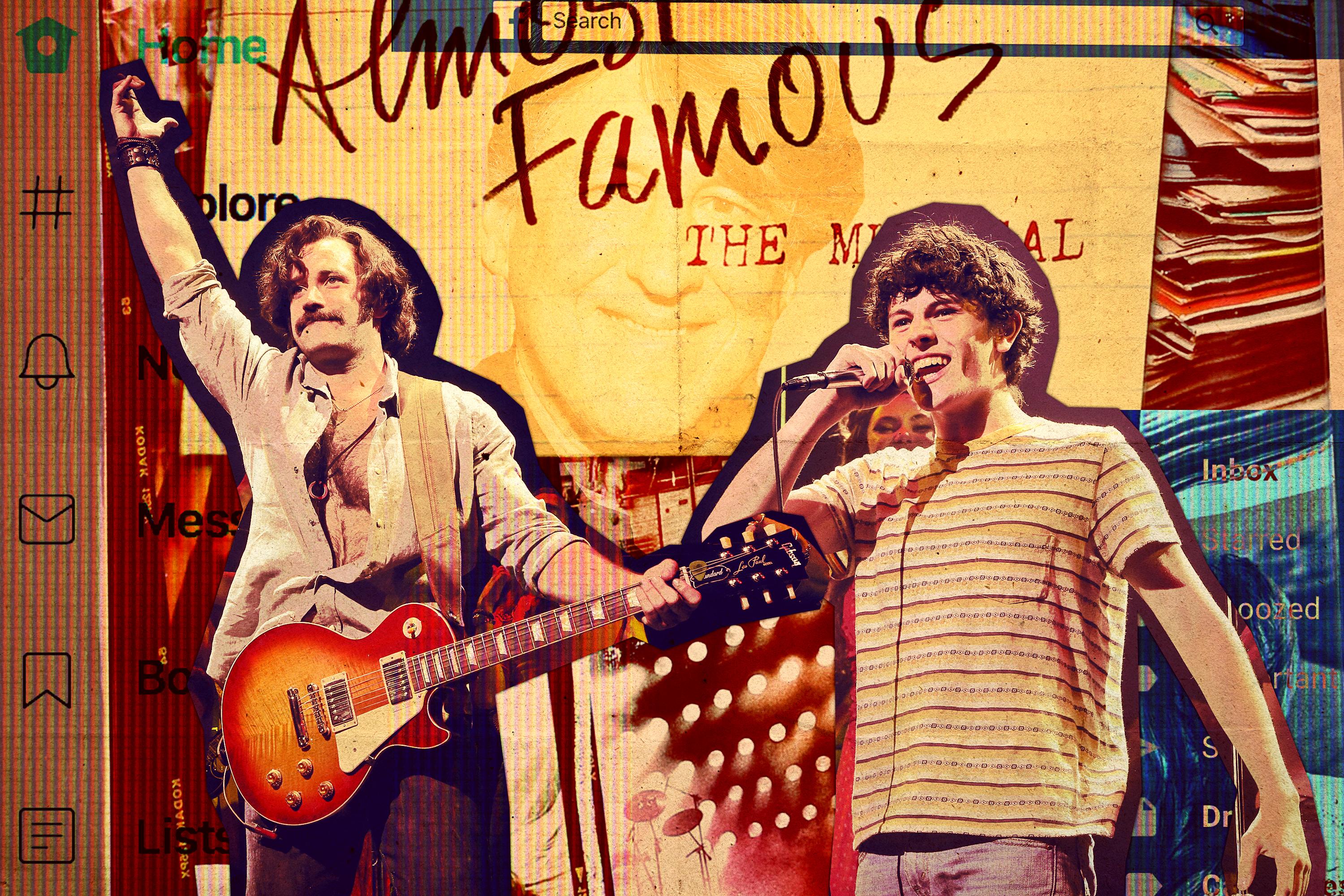

What’s the opposite of a gritty reboot? A trip to the cobbler for a polish and resoling? That’s Almost Famous: The Musical. It is, for one thing, a musical, one that shouts “I dig music!” from the rooftops when the characters aren’t literally doing that. Anyone familiar with the original film can guess the exact beats where the cast members give each other a knowing look before breaking out into song: Penny Lane’s most memorable flight of fancy leads into “Morocco,” a ballad of profound longing that could be sung by a Disney princess (and you know it’s about Morocco because it’s got a bendir in it). Miller’s mother addresses her community college class with the stilted rhyming of “Rock Stars Have Kidnapped My Son.” You better believe “It’s all happening!” results in a frantic ensemble piece, but it sounds nothing like LCD Soundsystem. These numbers were written by Tom Kitt, whose previous credits include SpongeBob SquarePants: The Broadway Musical, Jagged Little Pill: The Musical, American Idiot: The Musical, and a bunch of actual Green Day albums. I’ll trust the rave reviews thus far, but I just see a major missed opportunity in not giving a call to notoriously divisive Sun Kil Moon mastermind Mark Kozelek, who played Stillwater bassist Larry Fellows in the film; imagine having his greatest line reading evolve into one of his typical 15-minute rambles about the best barbecue joints across the mid-South.

Almost Famous: The Musical wisely reinforces the very qualities that earned the film version universal praise: warmth and heart, things that still strike me as liabilities in a period piece about a debaucherous time in the music industry. Like Penny Lane, Crowe sees the best in everyone and I can’t think of a single villain or lapse in judgment that has any lasting negative consequences. We’re all supposed to silently hiss at Dennis, the slick manager whom the label sends to replace Russell Hammond’s personal friend Dick Roswell; instead, Stillwater come off as so likable that you just want them to get their finances in order for once (plus, Dennis is played by Jimmy Fallon in an unconvincing attempt to break character). Penny Lane overdoses on quaaludes and recovers swiftly and off-screen; William and Anita Miller forgive their domineering mother; William’s article gets canned and then revived. It’s pure wish fulfillment for the mostly older crowd in attendance, an escape into an alternate reality where Led Zeppelin’s imperial phase had more sociopolitical impact than Richard Nixon’s presidency. Almost Famous can be enjoyed by people who don’t care about music journalism in the slightest, and that’s why it’s such a success. And yet, I think about the central conflict in an otherwise frictionless musical and Almost Famous is somehow even more relevant in 2019: If the boundaries between friendship and professionalism get any blurrier, will music journalism survive?

“If you’re a rock journalist: First, you will never get paid much,” Lester Bangs informs William in one line of dialogue that has certainly held up 46 years later. “But you will get free records from the record company. And they’ll buy you drinks, you’ll meet girls, they’ll try to fly you places for free, offer you drugs. ... I know.” Granted, Bangs’s advice mostly serves to pump up his own ego, and this speech is bundled into a greater musing on how guys like them will eventually win out, because the cool bands who get the girls don’t make art that lasts (maybe Todd Phillips could do the gritty reboot). But there’s a reason Elaine Miller’s hysterical repetition of “DON’T DO DRUGS!” is played for laughs. William might be naive, but even before DARE, a 15-year-old probably had a grasp of why taking strange drugs from strange people might not be in his best interests. But not for the reasons a music writer might: There’s the obvious quid pro quo for favorable coverage, but also an unspoken fear that if a critic gets even a taste of the hedonism rock stars experience on a nightly basis, they might feel more sympathetic toward artists who make hedonism their ultimate goal. And as Bangs makes clear in his distinction between the Doors and the Guess Who, being a drunken buffoon is acceptable if there’s a degree of irony in it. Note that while Stillwater’s Russell Hammond is portrayed as a generally soulful dude even when he’s trading the love of his life to Humble Pie for $50 and a case of Heineken, it’s only relative to his variably mute or delusional bandmates. He’s not a tortured artiste or even a Guy Patterson from That Thing You Do! whose artistic ideals are stunted by a merciless music industry; he’s just a guy from a small town in Michigan that doesn’t want anything to stand in the way of him and a good time.

But those aren’t the focus of Bangs’s concerns. Being the greatest music writer alive only makes you a bigger nerd among nerds, not cool; and as Bangs confides to William, “The only currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone else when you’re uncool.” Now, when I saw Almost Famous as a 20-year-old with an encyclopedic knowledge of Rolling Stone album scores, I still figured people were supposed to recognize that Bangs was sorta full of shit. He preaches critical distance and sees yokel-rockers like Stillwater as the embodiment of prefab cool, while feverishly raving about Iggy Pop and Lou Reed, who rank among the 10 coolest people who ever lived. “They want to get you drunk on the feeling that you belong,” he warns, and this is something that can corrupt a critic far more subtly and totally than the drugs, booze, and the groupie orgies. And with full-time music journalism, a realistic possibility for maybe a couple of dozen people at most in 2019, the main, if not sole, reason people still continue to write 2,000-word blog posts for free or spend eight hours putting together a $150 review or subject themselves to the soul-impoverishing micro-arguments of Twitter is because writers mostly operate in an economy where “belonging” is the primary form of currency. It’s easier to recognize than ever and thus easier to exploit.

I’m almost envious of how clearly the battle lines were drawn in 1973—William Miller is playfully referred to as “the enemy” by Stillwater, yet they let him into their camp because there’s an established symbiosis. Stillwater are big enough to be in consideration for the cover of Rolling Stone, but they’re still opening for Black Sabbath several albums in, so they have to shoot their shot with a magazine that famously didn’t think Led Zeppelin was cool enough. Miller wants his first big byline and he also wants to be accepted by one of his favorite bands, but Rolling Stone could easily throw the Who on the cover in a pinch, so both parties are going to try to make it work.

In August, the Columbia Journalism Review saw a grim future for deeply reported features like “Stillwater Runs Deep,” but not because publications would lack the financial or personnel resources to make them viable. Rather, there’s “a glut of digital publications [struggling] for access to artists who retain a greater degree of control over their narrative, with the help of an expanding field of publicists,” what veteran music writer Jeremy Gordon described as an “access problem.”

And why would any popular artist put themselves in the position of Stillwater, subject to being misquoted or misunderstood or misinterpreted by a writer or a publication whose agenda is something other than offering free PR? Why not go directly to the content-craving fans themselves through social media, or, in the case of Beyoncé, leverage unprecedented power into complete editorial control over an issue of Vogue? Just look at what happened to Madonna, who compared a not-entirely flattering New York Times profile to being raped; though that itself could’ve been one of her 3D chess moves to drum up some controversy for a new album that otherwise vanished from the face of the earth.

But while this might explain why modern-day William Millers won’t get to spend weeks at a time on a plane with their subjects (unless they charter it themselves), most people wouldn’t say music journalism is in a state of perpetual free fall because there aren’t enough Rihanna interviews to go around or because those that do get access don’t have a prepared list of questions. The savviest pop stars recognize how hungry most publications are for even the tiniest crumbs; after wriggling out of her latest jam caused by an awful lead single, Taylor Swift quoted positive reviews of Lover, bylines included, on her Instagram. What was worth more to those writers: the fee from a negative review or the possibility that Taylor Swift or whoever runs her Instagram will publicly acknowledge their existence? It’s Taylor Swift’s go-to move because it’s proved to be effective time and time again. “Taylor Swift Will Put This Blog on Her Instagram If We’re Nice Enough” was published a year ago in The Outline; it named a handful of scribes who were invited to the “Reputation Room,” a “cushy, thematically decorated private room” that welcomes VIPs on tour, as well as critics who should presumably leave with a lower reputation than when they entered.

But publications can still write dozens of articles about every Taylor Swift album cycle, even if she’ll never grant them any face time. The biggest problems in music journalism aren’t attributable to a lack of access. Putting aside the 1 percent of the pop music world, it’s probably the exact opposite.

There are ways to acknowledge bequests of belonging that are inherently seen as tacky (i.e., posing with the artist that you’ve just interviewed, retweeting an artist’s praise of your positive review). But with industry types, PR flacks, artists, and writers all crowding around the same water cooler on Twitter, where does friendship actually develop, to the point where a writer can no longer be “honest and unmerciful”? Is a mutual follow on Twitter crossing the line, or does that happen when you start trading tweets about the NHL playoffs? What about being friends on Facebook? What if you’ve hit up their PR to be on the guest list? What if you’ve had a pleasant exchange over previously positive coverage?

Maybe that doesn’t result in friendship. But at the very least, they’re now your coworkers, especially given how freelance writers and musicians are under even more pressure to concurrently curate and promote their personal brand. While “coworker” might sound objectively preferable to “friendship” in this context, you can have a heated disagreement with your friends and patch things up. Beef with a coworker and you might have to hide in your office for the next week. Or maybe not even bother showing up.

Lizzo has accelerated into a rarefied tier of stardom in 2019, due in large part to her ability to come off as approachable. Likewise, Lana Del Ray has always been. Both released wildly successful and critically acclaimed albums this year and both responded to their one lukewarm review the same exact way. “PEOPLE WHO ‘REVIEW’ ALBUMS AND DONT MAKE MUSIC THEMSELVES SHOULD BE UNEMPLOYED,” Lizzo tweeted in response to Pitchfork’s 6.5 review of Cuz I Love You; she deleted the tweet, but not before writer Rawiya Kameir could feel the full force of Lizzo’s diehard backers. Lizzo later offered to patch things up with access and belonging, inviting critics to join her in the studio. Venerated critic Ann Powers gave a mostly positive writeup to Del Rey’s Norman Fucking Rockwell, but took issue with LDR’s “persona” and “uncooked” lyrics. In response, Lana Del Rey aired out her displeasure to over 9.5 million Twitter followers, who took their shots at Powers, before the singer eventually backtracked, perhaps due to the rare backlash where people rushed to the defense of the critic.

When there’s a greater disparity between the critic and the artist, it’s easy enough to rehash Bangs’s “these people aren’t your friends” mantra. But even the smaller blogs that aren’t beholden to corporate interests almost never deal in negative criticism—most of them owe their existence to subscription models or strong relationships in the genres of music they cover. Why would they jeopardize any of that? Whenever younger writers ask me for advice, I take the opposite tack of Lester Bangs: Perhaps it’s not the affirmation they should fear so much as the negative reinforcement. It’s easier to tell someone to be “honest and unmerciful” when the most blowback a critic might get is a random email or, at best, a song in your honor.

Befitting its famously diplomatic author, Almost Famous resolves these enduring conflicts with a mutually beneficial ending: As with Crowe’s name-making profile of the Allman Brothers Band, Miller’s first Rolling Stone piece gets the cover because he was honest and unmerciful and mostly because Russell Hammond was sympathetic toward realness.

But in many other ways, Crowe plays fast and loose with history—for one thing, William Miller’s father was dead when he was in high school, whereas Crowe’s was very much alive. Similarly, Bangs might’ve been Crowe’s personal hero and the embodiment of fearless music criticism, but Almost Famous doesn’t have to follow his trajectory past 1973. “I’m home all the time,” Bangs tells William toward the end of Almost Famous, “I’m uncool.” But this doesn’t account for all of the times Bangs blatantly aspired for coolness and made friends with musicians when it was convenient for his fledgling recording career. It also papers over how he was unable to keep steady employment for extended periods of time—in particular, he was fired from Rolling Stone for “disrespecting musicians”—and remained a freelancer after leaving Creem in 1976 until his death at 33 by accidental overdose from opioids, benzos, and NyQuil.

Cameron Crowe, on the other hand, seemed to go against every piece of advice Bangs offered William Miller. “He covered the bands that hated Rolling Stone,” according to Fong-Torres, cozying up to FM staples like Yes, Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, and the Eagles (whose Glenn Frey is credited as the main inspiration for Russell Hammond). The producers of Almost Famous: The Musical “didn’t get a single turn-down on the existing songs they wanted to license,” a mind-boggling feat for a project that includes Led Zeppelin, Elton John, Deep Purple, the Allman Brothers Band, David Bowie, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Joni Mitchell, who was in attendance for the premiere. “Elton said, ‘You better use ‘Tiny Dancer’!,” according to Crowe, and Almost Famous’ most memorable musical moment is recreated in full. It’s possible that Almost Famous: The Musical exists solely because Cameron Crowe’s made more famous friends than probably any other music writer living or dead, and his success came because he didn’t see the critic-musician dynamic as inherently antagonistic. Almost Famous might’ve been Crowe’s love letter to the gloried past of music journalism, but the man who wrote it ultimately embodied its future.

Ian Cohen is a writer and registered dietitian living in San Diego. His work has appeared in Pitchfork, Spin, Stereogum, and Grantland.