How the Baseball Became an Unreliable Narrator

First it was juiced in the regular season, when teams set all kinds of home run records. Then it was dejuiced in the postseason, when it affected the outcomes of games and series. The changes made it difficult for teams and fans to anticipate how the ball would behave, but they may have also exposed a flaw in the stories we tell ourselves about the game.The Washington Nationals don’t win the 2019 World Series—the first in franchise history, in a thrilling comeback against the big, bad Astros—if Will Smith’s fly ball in Game 5 of the NLDS clears the fence, as expected off the bat.

It was the bottom of the ninth in L.A. The score was tied, after consecutive Nationals home runs off Clayton Kershaw the previous inning. A runner stood on first with one out, the Nationals just one heartbeat away from more October heartbreak.

So when Smith walloped a middle-middle slider 100.3 miles per hour toward right field and reacted by immediately flinging his bat into the air with a little hop out of the box, when his Dodger teammates catapulted over the dugout railing to begin to storm the field in celebration, when Nationals pitcher Daniel Hudson turned to trace the ball’s trajectory with a grimace, everyone seemed to know the series was over. The Dodgers would advance; Kershaw’s lapse could be forgiven. The Nationals would wonder yet again when playoff fortune might finally fall their way.

Except Smith’s series-winning home run didn’t clear the fence, and it didn’t win the series, and the Dodgers couldn’t race onto the field in triumph. The crushed fly ball fell into Adam Eaton’s glove on the warning track, 368 feet from home plate. Half an inning later, the Nationals would score four runs on a Howie Kendrick grand slam to win the series en route to an eventual championship.

“Wow,” color commentator Jeff Francoeur said after a moment of contemplation, expressing the entire audience’s reaction in a single syllable. “I thought Will Smith just ended it right there.” Then, after the cameras showed the dugout’s gleeful-then-somber reaction, “You see those guys thought he did, too.”

But the ball, contrary to Rasheed Wallace’s eternal ethos, lied. It lied all year, in fact. With apologies to Howie Kendrick and Gerrit Cole, Cody Bellinger and Pete Alonso, the star of the 2019 baseball season was the ball itself. The item that shares the very name of the sport is a bit like an umpire: involved in every play, yet noticed only when something goes wrong. Throughout the 2019 season, from Opening Day through Game 7 of the World Series, everyone noticed the ball—a fraught relationship that upset our collective understanding of the sport, and the suspension of disbelief required to invest in its stories.

The core of a baseball—as we’ve learned in detail in recent years—is made of cork, rubber, and yarn. The core of baseball, though—the sport, not the object—is a storytelling device: We follow for the twists and turns, try to glean clues about the events to come next, select and root for protagonists, and jeer the villains. It may look like narrative construction from a set of random numbers, but it’s those narratives that delight us through the summer months and sustain us through the winter with nostalgia and anticipation.

The Nationals in 2019 completed a tidy World Series narrative, the easiest to believe and promote: a perpetually cursed franchise that lost its most famous player, scuffled through 50 games, and recovered in time to enjoy three distinct playoff miracles—against Milwaukee, L.A., and Houston—and win a title. But that narrative can’t help but be subverted, at least on some itchy level in the back of the brain, by the confusion over the ball. Every expectation built by the 2019 season up until October meant the Nationals’ narrative should have ended on Smith’s would-be home run. That it didn’t, that the ball pulled an unforeseeable trick, forces confrontation of fundamentally frightening questions: What happens to a story when its narrator becomes unreliable? Can that narrative be reclaimed? And, even worse—what happens to our collective understanding of a story when we learn that the narrator has been unreliable all along?

The ball became a story early in the 2019 season, well before most statistical samples stabilize and narratives begin to form about the season in play. “The Baseball Is Juiced (Again)” read a Baseball Prospectus headline on April 5, so early that the Yankees and Astros were both below .500 and the Tigers and Orioles were both above. BP writer Rob Arthur used Statcast data to calculate the “drag” on the ball, which influences a batted ball’s air resistance and can thus change how far it travels. (Arthur has also written stories for The Ringer.) Lower drag means longer flies—and the early 2019 numbers were noticeably low.

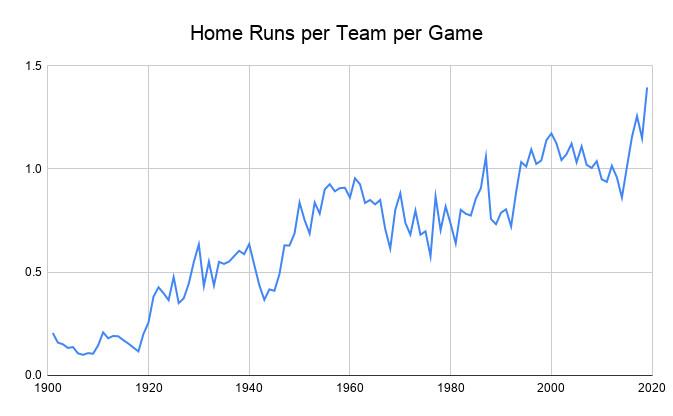

It might be more accurate, actually, to say that the ball re-emerged as a story early in the 2019 season, after first taking center stage in 2016 and 2017 as homer totals leaped across the league. Public analysts ran numerical calculations. They lab-tested baseballs. They cut into the balls themselves to analyze their innards. Various strands of evidence suggested that the balls had changed. And in May 2018, a committee convened by MLB to investigate the change concluded the same in an 84-page report: Increased home run rates were due to “changes in the aerodynamic properties of the baseball itself, specifically to those properties affecting the drag.”

The only problem was the MLB committee couldn’t figure out why those changes had occurred, as Rawlings—the ball manufacturer, which is owned by MLB as of 2018—hadn’t changed its processes of stitching the spheres together by hand in its Costa Rica factory. So when the “juiced” ball returned in 2019 after taking a year off, it seemed like the home runs would reach 2017 levels again, or more, without any known mechanism to slow the surge.

In the end, 2019’s longball total exceeded even the most hyperbolic expectations. The numbers are simply astounding. MLB batters hit 6,776 home runs last season, 671 more than the previous record and more than 1,000 more than any season before 2017. The Twins, Yankees, Astros, and Dodgers all broke the previous team record. Eight Twins hit at least 20 home runs, a record; 14 Yankees and 13 Blue Jays hit at least 10 home runs, besting the previous record, too.

Pitching staffs naturally set some records of their own. The Orioles, Rockies, Angels, and Mariners each allowed more home runs than any previous team in history, while the Phillies tied the all-time mark. The top (or bottom, depending on the perspective) 10 homer-allowed seasons in history have all come since 2016, including from the 2019 Yankees, who won their division and reached the ALCS despite their charitable staff.

This was the new sport, a game of contrasts: exciting yet stale, extreme yet simplified, visually dynamic (every batter could hit a home run, so a viewer could never look away) yet visually off-putting (all those jammed shots that somehow cleared the fence) all in one. Not everyone enjoyed the ball’s added liveliness, but at least the matter was momentarily settled. This was the sport that teams and players and fans knew in 2019.

Then came a plot twist, an October surprise on major league diamonds from New York to Los Angeles, Atlanta to Minnesota. The hyperactive ball stopped flying so far in the playoffs, even though MLB says playoff balls are drawn from regular-season batches. Anecdotally, well-struck balls that looked set to clear the fence fell short, fooling spectators, broadcasters, and the players themselves. Arthur ran the numbers again and found that the postseason ball looked wholly different from its regular-season counterpart—and, crucially, from every other postseason ball, with wildly disparate drag figures appearing every night.

The ball looked generally unjuiced compared to regular-season levels, but more broadly, Arthur concluded, the sport’s central object had produced “aerodynamic chaos.” A home run swing one night would generate a harmless fly out the next with seemingly no reason for the shift in outcome. Games and series were changing as a result.

According to a model Arthur built based on factors like exit velocity, launch angle, and ballpark, batted balls in the 2019 postseason “should have” produced 142 home runs if the ball were behaving as it did in the regular season. They actually produced only 95—meaning a third of the playoffs’ homers went missing.

Any possible takeaway from this seesawing effect is discouraging. “It suggests that MLB really has poor control over the manufacturing of the baseballs and specifically over the performance of the baseballs,” Arthur says. “And that’s kind of a staggering and unfortunate fact that has been reinforced over the last few years.”

Just as frightening is what comes next, as players and teams plan for next season and beyond. Last week, another MLB-convened panel of scientists identified a change in seam height as partially responsible for the decrease in drag in the 2019 regular season—but only about a third of it. The remaining two thirds, they said, are still unexplained, and they couldn’t discern why drag had increased and grown more erratic in the postseason.

So what does this continued mystery mean for the 2020 season? “The short answer,” says Meredith Wills, one of the public analysts responsible for investigations into the ball’s composition, “is that [after] what we saw in the 2019 postseason in particular, there really is no guarantee that there is going to be a consistent baseball next year.”

MLB actors like control—front offices over their decisions, their players, their sources of data that increasingly encompass ever more aspects of athletes’ lives; players over their bodies, their performances, their superstitious routines every day they play. So it has become the source of some actors’ utmost frustration that their control over the central object in the sport has dissipated for no identifiable reason.

“It’s a fucking joke,” Justin Verlander memorably said midseason. The changed ball didn’t prevent the Astros ace from winning his second Cy Young award in 2019, but he had good reason to decry the new ball, allowing a career-high 36 home runs despite allowing a career low in overall hits per game.

Nor was Verlander the only involved party to wish for a return to normalcy—or even predictability. “I think as players, we just want some transparency and some consistency with the answers,” Nationals closer Sean Doolittle said. Athletics GM David Forst said after the season, “I can only speak for our organization, but what we want is consistency, and we’ll build a team around that.”

As the player development improvements in the 2010s have clearly displayed, baseball knowledge is power, so Forst’s seemingly simple desire resonates. If a team knew the liveliness of the ball to come, it could embrace certain advantages in player acquisition and development. A 2014-style ball would render fly-ball pitchers more valuable; a 2019-style ball would reduce the need to chase power in the lineup because even feckless middle infielders can thwack 20 dingers. Pitching coaches might change where they instruct their charges to aim in the strike zone; batters might trace new swing paths to generate more fly balls, or seek more grounders depending on the ball’s flight pattern; coaches might position their fielders differently, as the Cardinals did in October when their analysts calculated less distance on playoff fly balls.

Yet that seemingly basic level of predictiveness has abandoned the sport entirely. “In terms of the way clubs prepare for the ball in a certain year, we can give them some information,” Morgan Sword, a senior VP for MLB, said at a press conference last week, “but I don’t think we’ll ever get to the point where they can have complete certainty about that.”

That’s a universal disappointment, but how teams react is a more individual matter. One answer is to throw one’s arm in the air and shrug. “We will play with whatever balls they deliver to us,” says one front office executive. Another notes that the lack of predictability for the ball’s behavior separates it from other areas a sophisticated front office might excel. “You can get out ahead of things when you have the information. Smart teams can have progressive ideas when they’re able to use data,” he says. Changing philosophy based on the ball, conversely, would amount to “guessing that the data’s going to be a certain way.”

A team’s place in the standings could affect its push to seize every possible fractional advantage for the 2020 season. One front office executive for a team that didn’t contend for a playoff spot last year wrote in an email that “where we are in the standings, we are the least likely to have it influence roster decisions.” Conversely, a team in Philadelphia’s position, pushing for the 2020 playoffs, is “spending a lot of time researching it,” Phillies GM Matt Klentak told Yahoo.

Even for the noncontenders, however, the uncertain ball further complicates analysis for non-MLB players. Forecasting prospect performance is already an inexact science, which is only compounded by the inexactness of the new ball and its ripple effects. The two Triple-A leagues used an MLB ball this year instead of the old minor league sphere, and both saw home run rates rocket upward by nearly 60 percent. Every other full-season minor league, which all kept the same minor league balls as before, saw rates in line with 2018. So if a prospect saw his power rise at Triple-A, did he make real gains or benefit from a bouncier ball alone?

Change in Minor League Home Run Rates

This strange new world of uncertainty and confusion could persist for some years to come, moreover, while MLB and Rawlings figure out why, exactly, the ball has changed so dramatically and unpredictably this half-decade. “Unfortunately, we have not yet been able to identify these factors, despite lots of effort,” scientist and panel member Alan Nathan said at last week’s press conference.

Other sports with equipment issues have been able to make quicker fixes. The NBA switched to a new ball made of synthetic materials in 2006 but reinstated the old leather ball after just two months because of vehement player complaints. The official ball developed for the 2014 World Cup sought to fix the problems from 2010, when the Jabulani design, which tended to produce a knuckleball effect in flight, frustrated participants.

But the problems behind the NBA’s synthetic ball and the Jabulani were more easily identified. The baseball has a bit of an endless cause-and-effect problem: We know there are more homers because the ball is traveling farther, and we know the ball is traveling farther because it has reduced drag, and we know it has reduced drag because it has a lower seam height, among other causes, but we don’t know why it has a lower seam height, and so on. And if MLB’s experts can’t identify the root issue, there’s little hope of resolving it in a considered, consistent manner.

All signs point to more muddled understanding of the factors behind the ball’s erratic flight. The future of the sport could be a yearly—or monthly, or daily—reexamination of how many home runs might fly that year or month or day, and how teams and players can adjust their strategies accordingly, if such foresight is even possible.

Undoubtedly, the composition of the baseball affects the sport’s future. What hadn’t been clear until recently, and what poses far more insidious problems for fans, is just how much the current ball crisis would cause us to question the sport’s past.

On some level, of course, baseball fans know that context drives performance, results, and records. In 1961, for instance—the very same year that literary critic Wayne C. Booth coined the term “unreliable narrator” in The Rhetoric of Fiction—Roger Maris benefitted from expansion (he homered 13 times against the two new American League clubs) and an increased schedule length (the AL added eight games to reach 162) to set the new single-season home run record.

This season, Pete Alonso set a rookie record with 53 home runs, which might merit some sort of ball-related asterisk—except he broke the previous mark of 52 set by Aaron Judge in the juiced ball season of 2017, which itself broke the previous mark of 49 set by Mark McGwire in the “rabbit ball” season of 1987.

As these examples indicate, the ball has driven extreme outcomes before, dating all the way back to the 1910 season, if not earlier. Sometimes the changes were unintentional, the result of either mistakes or outside forces; home runs jumped in 1977, for instance, when the league switched from Spalding to Rawlings as the ball manufacturer. In 1918, home run totals dropped in the second half because the United States’ entrance to World War I precipitated a shortage of baseball-building materials. “The balls, now wound with inferior yarn and covered with lower quality horsehide, were even deader than before,” writes Glenn Stout in The Selling of the Babe.

Other times, the change has been, if not decidedly intentional, at least presumed as such by suspicious minds. When Verlander accuses commissioner Rob Manfred of intentionally making the balls friendlier for home run hitters, he steps into a century-long line of conspiracy theorists. Stout quotes sports columnist Ring Lardner, who wrote upon the league’s first-ever homer boom in 1920, “The masterminds that control baseball say to themselves that if it is the home run the public wants to see, give them home runs. So they fixed up a ball that if you don’t miss it entirely it will clear the fence.”

Which category 2019 occupies is a conspiracy for another time; after the 2014 season, the lowest-scoring non-strike year since 1976, Manfred reportedly approached the players union about tinkering with the ball design so that it flew farther. Of course, it’s also possible that a hand-driven, non-automated process like that which creates the MLB ball produced a systemic error organically. After all, these changes are quite small—an adjustment in seam height on the scale of a single human skin cell can boost home run rates by a noticeable amount. Merely increasing the average flight of a well-hit fly ball by 5 feet yields a 10-15 percent increase in homers leaguewide.

Either option is troubling, of course: Either the juicing was intentional and MLB lied, or the league truly doesn’t know why it happened and has no control over the object in the game that affects every single play. The latter might even be worse, as it forces us to wonder whether MLB had no control over the ball in the past, too.

Morgan Sword, from MLB, said in last week’s press conference that the collective baseball world needs to “accept the fact that the baseball is going to vary and the performance of the baseball is going to vary.” Asked whether players and fans are comfortable with that state of affairs, Sword responded with a seemingly dismissive line that, in fact, raises many more epistemological concerns.

“I mean, it’s always been the case,” he said. “The baseball has varied in its performance probably for the entire history of our sport.”

We already know the extremes to which an altered ball can affect outcomes in a close playoff series. Rob Arthur’s model estimates that Smith’s fly ball against the Nationals would have cleared the fence 63 percent of the time if the ball acted as it had during the regular season. Balls hit with the same characteristics as Smith’s (exit velocity between 99 and 101 miles per hour, launch angle between 25 and 27 degrees) traveled an average of 385 feet in March through September; an extra 17 feet, or even 7 feet, would have won the Dodgers the series and eliminated Washington early in October yet again.

Similar scenarios presumably occurred before the advent of Statcast in 2015 allowed us to measure drag reliably. So when David Freese snuck a triple past Nelson Cruz’s glove to prevent the Rangers from winning the 2011 World Series, was that particular ball a bit more juiced than another that pitcher Neftalí Feliz could have selected? Would Dan Johnson’s and Evan Longoria’s “Game 162” home runs have cleared the fence with a different ball? What about any number of the other hundreds of memorable plays throughout league history; can we imagine what-if alternatives for all of them, if only the ball hadn’t differed slightly from its neighbor?

A 2000 study funded by MLB and Rawlings found that “two baseballs could meet MLB specifications for construction but one ball could be theoretically hit 49.1 feet further.” At that large a gap, the MLB “specifications” don’t seem very specific at all. (The 2018 ball report notes of this disparity, in quite the understatement, “Clearly, this standard is unreasonably large.”) The more we learn about the ball’s uncertainty, and the fact that its only consistent nature is its inconsistency, the more we have to confront the fact that so many of the stories we’ve grown up with and cheered for and cherished are more unreliable than we want to believe.

This problem is particularly profound in baseball, a sport built on nostalgia, where records are sacrosanct and the Hall of Fame fiercely debated. Few basketball fans could name Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s career point total without checking a basketball card; few football fans know Peyton Manning’s touchdown total by heart. But baseball fans know their historic numbers like another roster alongside that of their favorite team: 56 for Joe DiMaggio, 755 for Hank Aaron, 61 for Maris, and so on.

The sport’s present is now affecting its past, twisting it, distorting its presumed purity. This is a main reason the steroids scandal mushroomed in baseball like in no other major American sport, as all of Barry Bonds’s and Mark McGwire’s and Sammy Sosa’s drug-enhanced home runs shattered baseball’s historical mosaic. But even the steroids era is less intrusive than the knowledge of ball-enhanced home runs and flyouts throughout the sport’s history. Steroids were (mostly) confined to a strict, cordoned-off decade, while the ball has apparently been off-kilter for the entirety of the sport’s existence. And steroids were (mostly) confined to a select, known group of players, while the ball has affected every athlete on every pitch dating back to Abner Doubleday’s invention of the game.

Doubleday didn’t actually discover the sport; that’s a myth, a result of an unreliable narrator, a story we tell ourselves about the grand design of this incredibly intricate, bizarrely beautiful sport. For front offices and present-day players, of course, the chief ball-related concern is how it might behave in 2020, and whether it will again shift come playoff time. But the problems run much deeper. They worm into the very essence of the sport—from the essential element of the ball through the essential stories and moments that define the 120-year-old league. That’s a whole lot of baseballs that might have varied from the norm in key moments—that’s a whole lot of historical narratives to question anew.