Does the Movie Industry Need an Unsafe Space?

If so, the micro-studio Cinestate—and its burgeoning media arm—is here to make us a little less comfortable. Meet the merry band of ultraviolent genre enthusiasts trying to upend independent movies.It’s the last day of shooting on Run Hide Fight, and we’re crammed into the back corner of a hallway in a Comfort Inn in Red Oak, Texas, a tiny Dallas suburb that had once served as the exterior location for David Byrne’s 1986 curio True Stories. This $1.5 million production isn’t large enough to affect hotel business—at one end of the hall, housekeeping is still wheeling in and out of rooms, and, outside the window, a worker surreptitiously glances inside as he clears the branches that have tangled around a satellite. The filmmakers are treading lightly in the few hours they have in this location. At the end of a five-week shoot, everything seems second nature. They quietly go about their business, getting sustenance from a giant communal bag of SkinnyPop and a caffeine jolt from the espresso machine that cinematographer Darin Moran has been manning under his video cart.

They can stay quiet for only so long. The stairwell at the Comfort Inn is standing in for a primary location that’s only a single floor, and the heroine, a high school student in terrible trouble, is fleeing armed assailants down the stairs. The film’s producer, a commanding 27-year-old named Amanda Presmyk, examines the lead actress, Isabel May, as she’s about to head into the breach. Presmyk wonders whether the blood crusted under her nose and across her forehead is a “too advanced look for her,” and she fiddles with May’s hair, which wants to be more sculpted than it should be for a wounded girl who’s been fighting for her life. But they can’t get too fussy on a day that began at 1 p.m. and won’t wrap until after sunrise the next morning.

Every shot on the stairwell includes a blast from the fog machine and frantic action, but they’ve saved the noisiest disruption for last. The weapon master has loaded blanks into a 12-gauge shotgun, and the sound of the blast, reverberating off the concrete, will be loud enough to knock a star or two off the hotel’s TripAdvisor ratings. The biggest concern is that all doors are manned and secured before the take. This is Texas, after all, and there are men in trucks who are fully prepared to return fire in situations like this one. I politely decline the earplugs getting passed around, figuring that I’ve seen Dinosaur Jr. in concert and can withstand an aural assault of any kind. In retrospect, it was probably a mistake: The jolt shocks me a little, even though I knew it was coming.

Now here’s a jolt for you: The elevator pitch for Run Hide Fight is “a 17-year-old female Die Hard in the middle of a school shooting.” For many, the recoil from that premise is probably 12-gauge-shotgun-esque, given the plague of mass shootings that continue to shatter communities across the nation. In fact, the film’s cast and crew paused production for a moment of silence on November 14, when a 16-year-old gunman killed two students and himself at Saugus High School in Santa Clarita, California. The script was passed around Hollywood studios like Paramount, which expressed interest, but writer-director Kyle Rankin admits that, after Parkland, it had become “radioactive.” Everyone I talked to for this piece confessed to initial trepidation about the project, which scared them and still seems to scare them, despite their firm belief that it can play a positive role in the conversation. But in an increasingly risk-averse industry, the answer was a hard “no.”

Enter Dallas Sonnier, the founder and CEO of Cinestate, a rapid expanding film production, distribution, and publishing operation in the city that bears his name. He was born Joseph Sonnier IV in the city’s Highland Park neighborhood, where he currently resides with his wife and three young children. But the childhood nickname “Dallas” stuck, which has a tendency to turn mundane conversations into an Abbott and Costello routine. (After landing in Dallas that Friday morning, for example, I was told that Dallas would drive me to set.) But the name makes more sense when you meet Sonnier, a tall, imposing 39-year-old who holds the company together like a gravitational force, absolutely confident that the risks that seem extreme from the outside are, in fact, part of a prudent and cohesive vision. And if there’s one thing certain to raise Sonnier’s ire, it’s being told he cannot do something.

Not only is Run Hide Fight being bankrolled and distributed by Cinestate, Sonnier is also using it as the launch title for Rebeller, a new branch of the company that handles what he calls “outlaw cinema.” The Rebeller banner will essentially complement Fangoria, the legendary horror magazine that Cinestate bought and revived in February 2018, turning it into a robust print quarterly and website run by Phil Nobile Jr., formerly of Birth. Movies. Death. Under Cinestate, Fangoria has also been turned into a brand name for the company’s podcasts and horror productions, starting with last year’s Nazi-themed gore comedy Puppet Master: The Littlest Reich and continuing last September with Chelsea Stardust’s clamshell-box throwback Satanic Panic. Next year will bring Joe Begos’s VFW, which pits war veterans against rampaging punk mutants, and a remake of Stuart Gordon’s 1995 film Castle Freak that reportedly hews closely to H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Outsider.”

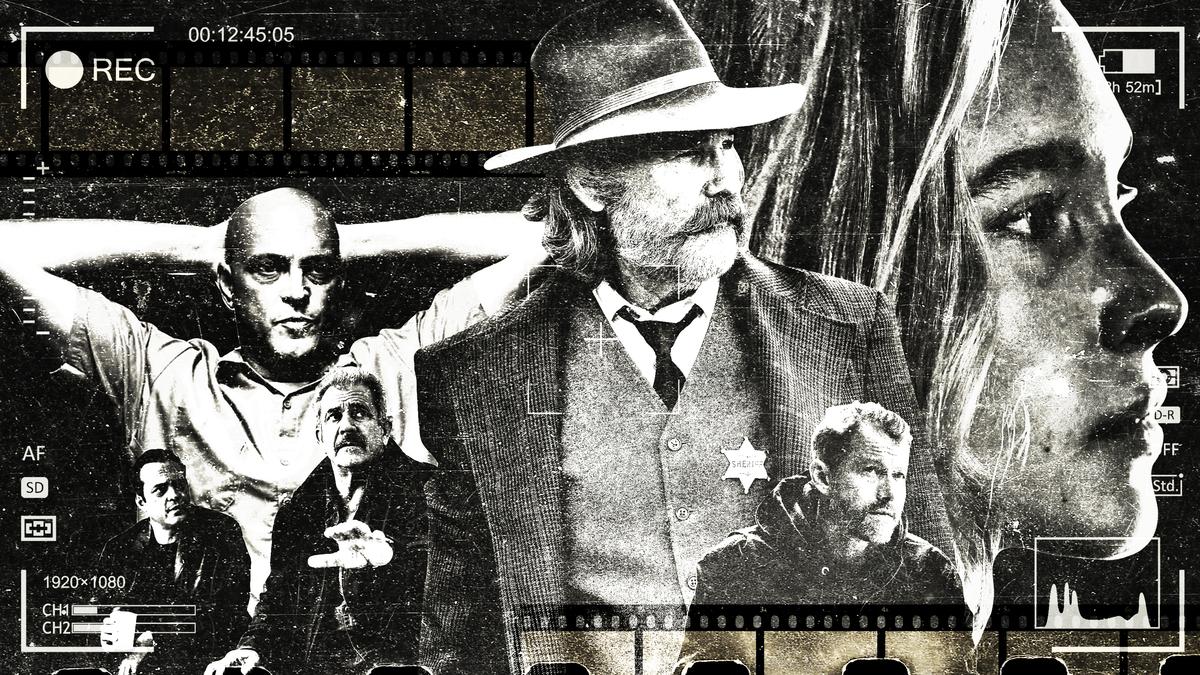

Rebeller will handle all genre fare outside horror, which makes it a natural home for a provocateur like S. Craig Zahler, the filmmaker who put Cinestate on the map. All three of Zahler’s films—the ensemble Western Bone Tomahawk, with Kurt Russell and Richard Jenkins; the two-fisted jailhouse odyssey Brawl in Cell Block 99, with Vince Vaughn; and the recent policier Dragged Across Concrete, with Vaughn and Mel Gibson—have gotten attention for their hyperviolence and reactionary politics, though Zahler and Sonnier are both cagey about the conservative sentiments critics often read into their work. The singularity of Zahler’s work is harder to dispute, characterized by old-school genre toughness, uncompromising brutality, moral ambiguity, and a gift for slow-burn storytelling and observation that pushes his movies well past the two-hour mark. (Bone Tomahawk and Brawl in Cell Block 99 are the shortest, and they clock in at 132 minutes apiece.)

In addition to Run Hide Fight, which Sonnier intends to distribute through Cinestate in late summer or early fall of next year, the Rebeller flag will also fly over the Universal thriller Till Death, director Aharon Keshales’s follow-up to Big Bad Wolves, starring Jason Sudeikis as a parolee for armed robbery who tries, with great resistance, to give his cancer-stricken childhood love (Evangeline Lilly) the best last year of her life. Less is known about Shut In, about a mother protecting her children from a violent ex, but Sonnier loved the script by first-time writer Melanie Toast, and Cinestate will produce the film for New Line. Till Death and Shut In are both larger operations than completely in-house productions like Run Hide Fight will likely be, but even then, the goal is to square commercial potential with the “unfiltered” grit and intensity of a Cinestate film.

To keep the label in line with Fangoria, Cinestate is also launching the Rebeller website, which will mirror Fangoria’s mix of aggregation and original features from writers and filmmakers. The site’s editor-in-chief, Sonny Bunch, is a culture columnist for The Washington Post and has contributed film reviews for conservative outlets like The Washington Times and the Washington Free Beacon, where he was also the executive editor. Bunch likens the aggregation section of Rebeller to the Drudge Report, which links directly offsite to various publications, and he plans an ambitious menu of essays, features, and retrospective pieces that fit within the site’s conceit. Bunch’s opening-day manifesto on “Outlaw Cinema” clarifies what is and isn’t “a Rebeller film”—of the recent war movies, for example, Midway doesn’t qualify but the action-oriented 1917 does—though I got the impression from several people at Cinestate that Lee Marvin is a patron saint.

The idea behind Rebeller the site and production label—along with Fangoria the magazine, site, and production label—is an integrated brand reinforcement, with the site as a daily hub for fans of hardcore genre filmmaking. An unsafe safe space, if you will. The communities that grow around Rebeller and Fangoria become the core audience for the films that Cinestate releases and those releases, in turn, bring viewers back to Rebeller and Fangoria. Launch-day features on the site include part one of a two-parter by blaxploitation legend Fred “The Hammer” Williamson on getting into the movie business, and a piece by Sonnier on producing nine Stone Cold Steve Austin movies in four years. (Some of them, it turns out, were not so great.)

There are movies made for everyone, and Disney makes them and they make them very well and they make a ton of money with them. [Cinestate’s] movies aren’t for everyone. They’re going to appeal to a select—I will say ‘discerning’—audience, and hopefully they’ll enjoy it and spread the word.Sonny Bunch, RebellerMedia’s editor-in-chief

Bunch has more essays lined up by critics like Sheila O’Malley and Abbey Bender, filmmakers like Zahler and Fred Raskin, who edited Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, and some regular columnists to be named later. He’s also cohosting a movie-review riff on the “Left, Right, & Center” political podcast called “Across the Movie Aisle” with the Post’s Alyssa Rosenberg, Bunch, and Reason’s Peter Suderman as left, right, and center, respectively. (“I’m all about overcoming ideological barriers, right?” Bunch jokes. “By mutual artistic appreciation.”) Though Bunch is known for poking at liberal cultural perspectives in print and on Twitter, he confesses to having grown tired of the “unpleasantness” of the D.C. political scene. He’s always considered himself a cinephile and a critic first, and Rebeller is giving him the chance to build a sensibility-driven site from the ground up.

“There are movies made for everyone,” says Bunch, “and Disney makes them and they make them very well and they make a ton of money with them. [Cinestate’s] movies aren’t for everyone. They’re going to appeal to a select—I will say ‘discerning’—audience, and hopefully they’ll enjoy it and spread the word. Every once in a while, when I’m feeling a little like, ‘What am I doing here?,’ I just throw Bone Tomahawk into Twitter search and see people talking about it, years later.”

The Cinestate office occupies half of a modest two-story in a row of small brick buildings in Old East Dallas, but the space doesn’t seem likely to accommodate it for long. Even with Run Hide Fight shooting half an hour away, every corner of the place is occupied: Nobile and his managing editor, Meredith Borders, have improvised a space for themselves to put the finishing touches on the new print edition of Fangoria, and I’m introduced to an accountant, an analytics person, and an important gatekeeper named Preston Fassel, who’s first line of defense on the screenplays that pass through Cinestate. The walls are festooned with beautiful Mondo posters for films like The Shining and The Cabin in the Woods, and the Fangoria purchase has given Cinestate its own version of the Criterion Closet, where all the back issues are neatly stored and sometimes signed by visitors like Tony Todd, who played the original Candyman.

In the back of the first floor, one corner room, presided over by a still-boxed Chucky doll and other props and memorabilia, there’s an expensive-looking sound board and microphones set up for the company’s podcasting network, which currently includes shows like Post Mortem, hosted by director Mick Garris, and The Narrow Caves, an audio horror story written by Zahler. The other corner room contains decades of press kits, slides, and other promotional materials from the Fangoria archives. When Cinestate bought Fangoria, Sonnier tells me, these assets were stacked floor to ceiling in storage closets on Long Island, and movers dumped them into the room. “It took us, no shit, a year to get through it all.”

The Cinestate staff likes to plunder the archive for treasures, and today a slide projector is full of stills from The Lost Boys, a film with special significance for Sonnier. His parents were extremely permissive of his moviegoing habit from a young age, but they wouldn’t let the 7-year-old Sonnier see The Lost Boys—which, in keeping with his grown-up aversion to the word “no,” invited an obsession. He liked action movies as a kid, not just the new films by Sylvester Stallone or Arnold Schwarzenegger, but the low-budget genre fare from companies like Full Moon Features or Cannon Films, which had a rawer aesthetic that Cinestate seeks to emulate. As a producer, Sonnier expresses equal admiration for Roger Corman and Jerry Bruckheimer: Like Corman, he’s refining a formula to eke out profits on low-budget, director-driven exploitation films, but Bruckheimer’s commercial packaging and populist instincts have him thinking bigger.

In the early part of Sonnier’s career, he seemed firmly on the Hollywood track. He lived in Los Angeles for 16 years, starting with four at the USC film and business school before cutting his teeth at the United Talent Agency and eventually getting into management, because he wanted closer access to the production side. Though he managed several huge talents in the making—Greta Gerwig was a client, as was future Russian Doll cocreator Leslye Headland—he had always felt like “a man on Mars” in L.A., and he was feeling creatively restless.

Sonnier makes decisions on instinct, and his instincts were telling him that Zahler’s script for Bone Tomahawk, a gruesome Western about a posse that tries to rescue captives from savage cave-dwellers, was the way forward. He’d managed the prolific Zahler through 25 scripts for films and TV pilots that were sold but never produced, in part because he was not inclined to take studio notes. “He wasn’t going to dilute anything or shorten it or cut a scene,” says Sonnier, “because everything’s a domino to him, and if one drops, the whole thing falls apart.” For years Sonnier and Zahler tried to get Bone Tomahawk off the ground, and Kurt Russell and Richard Jenkins were attached, but financiers kept passing.

Eventually, when Russell was about to pull away, Sonnier cobbled together money from a U.K. production company called the Fyzz, took out a personal loan, and mortgaged his house to get Bone Tomahawk made. The gamble paid off: The film sold to RLJ Entertainment for $2 million on a $1.8 million budget, and made much more on the back end, enough for Sonnier to save his house and plot a return to his hometown, where he could turn Cinestate into a renegade outfit between the coasts. It also created a rough business model for the company, so long as budgets are low. Except you’re not supposed to have an independent movie studio in Texas. You’re not supposed to revive a print magazine in the 2010s. You’re not supposed to make a movie with Mel Gibson. You’re not supposed to have a theatrical run for low-budget genre movies anymore, which Sonnier intends to do for Cinestate releases. And you’re probably not supposed to launch a new label with a daily film site and a Die Hard–style thriller set in the middle of a school shooting.

Sonnier is convinced there’s an audience eager for the types of risky, hard-edged films that don’t have a natural home at multiplexes or arthouses and don’t fit into the glossy ethos of streaming services. “We will put our money where our mouth is and prove it,” he says. “Or die trying.”

A lot of Sonnier’s counterintuitive impulses are hard to understand, but the tragedy at the center of his life makes them all the more confounding. Within the space of two years nearly to the day, in 2010 and 2012, Sonnier lost both his parents to separate incidents of domestic gun violence. Though he remembered a happy upbringing with his younger brother and a neighborhood friend who would become an unofficial member of the family, his parents got divorced when he was a young adult. His mother, Becky Gallegos, had remarried and relocated to the town of Fredericksburg in central Texas, but she was unhappy with her second husband and announced that she planned to divorce him. As she was packing her bags, he drank a bottle of Jack Daniels, shot the family dog, and killed her before turning the gun on himself.

We will put our money where our mouth is and prove it. Or die trying.Dallas Sonnier, Cinestate founder and CEO

His father’s murder was even more complicated. Bachelorhood had been fruitful for Dr. Joseph Sonnier, a pathologist, but he wasn’t aware that his new girlfriend had been the other woman in an extramarital affair that had broken up a marriage. When the man who’d left his wife proposed to her, she turned him down, because she had met Sonnier’s father in ballroom dance class and fallen for him. Sonnier says his dad came home one night to find a 6-foot-5, 380-pound stranger asleep on a lawn chair in his backyard, apparently tuckered out from stalking him on a 100-degree summer day in Texas. When he knocked on the window from inside his kitchen to wake the man up, the stranger pulled a gun out of a backpack, shot him multiple times through the window, entered the house, and stabbed him 11 times. Sonnier and his family later learned the man was hired by his girlfriend’s jealous former lover, the one who’d had his proposal turned down, to check into her new squeeze.

The years leading up to the production of Bone Tomahawk were plagued by the stress of police investigations and multiple murder trials and the unimaginable grief of losing both parents under such horrific circumstances. When the trials were over and Bone Tomahawk had paid off, Sonnier chose to come back home to Dallas to make movies that are known for—and defined by—their extreme violence. It would seem to take Olympic-level compartmentalization for Sonnier to sell his house in Calabasas (to Kylie Jenner, of all people!) and move his family to Highland Park and run Cinestate, like a man deliberately choosing to set up residence in a haunted house. And yet he’s always inclined to steer into the curve. Over lunch, he tells me he’s in negotiations with the current owner of his childhood home to loan it out for his 40th birthday party next year. Sonnier was notorious for throwing parties in high school and wants to re-create the experience. No ghosts allowed.

It can be a little hard to pin Sonnier down ideologically: He considers himself libertarian-leaning (“I tell no one how to behave”) and uses the language of self-starters and free speech absolutists, but he’s not dogmatic on any one issue. When I ask him about gun laws, in the wake of his parents’ deaths and mass shootings of the kind depicted in Run Hide Fight, he takes a moderate stance. “I want to protect my home,” he says. “And I want people to be able to hunt. I also think it’s absurd that we have high-capacity magazines. I think it’s ridiculous that we have weapons of war. I want to do whatever it takes to keep my family safe and provide for my family. Outside of that, I think everything is up for grabs.”

In prefacing his defense of Run Hide Fight, Sonnier is careful to express respect and sympathy for families of domestic gun violence and school shootings, because he knows firsthand what it’s like. But when he encountered the script, he said, “I saw it as the cathartic journey of a girl who got to fight back and kill her abusers.” And he insists that the film can have a positive role to play in a national conversation that’s of keen personal interest to him. “I hate that this is the state of affairs for our kids,” he says. “It’s fucking miserable and I want to fix it. I’m not a politician, so I can’t change the laws, but I can change some hearts and minds through movies, through our art, and through our company.”

Later that afternoon, Sonnier walks me through the main location for Run Hide Fight, a recently abandoned middle school in Red Oak that could kindly be dubbed “nondescript,” but more precisely called a remnant of a period in the mid-1980s when schools were architecturally indistinguishable from prisons. It’s the ideal Everyschool for the film, but there are fun little touches throughout the fictional Vernon Central High School, home of the Vipers, like the scotch-taped notifications on bulletin boards and classrooms, and posters for an original school musical called “Goodbye Trisha.” On one wall, there’s a collage of small, individualized banners around the prompt “Where will you be next year, Seniors?” made poignant by the fact that some of them won’t live to see graduation.

Sonnier starts with the cafeteria. He points to the window where four Vernon Central students—the dead-eyed ringleader Tristan (Eli Brown), doughy outcast Kip (Cyrus Arnold), and two siblings, Chris (Britton Sear) and Anna (Catherine Davis)—smash a van into the building during lunchtime with a detailed plan for maximum casualties. In another echo of Die Hard, our hero, Zoe (May), happens to be in the bathroom when the shooting starts, but Sonnier points to the kitchen, where she accidentally draws attention to herself. Earlier in the film, Zoe’s capacity to take on four assailants is established through a morning hunting trip by her father, played by Thomas Jane. Her recently deceased mother, played by Radha Mitchell, becomes an imaginary companion of sorts, counseling her through this terrible ordeal.

Down the hall from the cafeteria, Sonnier shows me the area near the principal’s office where an explosion is detonated, though it’s been turned into a makeshift production hub now, a place to throw our coats on this unusually chilly day in November. In an editing bay set up inside the library, Sonnier has arranged all the money shots for my edification: three different explosions, the van smashing through the cafeteria window, Treat Williams’s sheriff dodging a fusillade of bullets coming at him from inside the school. Cinestate may not spend a fortune on production, but it gets a literal bang for its buck. The Standoff at Sparrow Creek, a formally impeccable thriller the company released earlier this year, is mostly a Reservoir Dogs–type scenario about a militia penned into its hideout, but when it’s time for the standoff to end, the great bursts of gunfire are staged for maximum impact.

There are two scenes on tonight’s shot list: One is a backward-moving tracking shot of Zoe running down the hallway, warning students to get out, that recalls the drifting camerawork on the most famous movie made about school shootings, Gus Van Sant’s Elephant. The other is far more complicated. One of the sick ironies of Run Hide Fight is that the attack takes place during Senior Prank Day, so not only do some students mistake the mayhem for a joke, but there are obstacles, like a Slip ’n Slide, scattered around the school. The teacher’s lounge, for example, has been filled with hundreds and hundreds of balloons—and it’s here where Zoe gets the jump on Anna, the one female attacker, and tries to disarm her in a fog of colorful, popping balloons.

Over the five hours it takes to get an acceptable master shot, the production interns and other members of the crew are in a nearby classroom, inflating dozens of balloons that are brought out in billowing trash bags. These balloons are added to the ones already jammed into the room, including a wall taped together in front of a big light that’s giving the cinematographer fits. This darkly whimsical conceit recalls Rankin’s stint on the second season of Project Greenlight, when he and his codirector, Efram Potelle, were chosen to direct Shia LaBeouf in The Battle of Shaker Heights on the basis of their funny short films. Over 16 years later, Rankin is still grateful for the experience, but it turns out that following first-time filmmakers with multiple cameras as they try to make a low-budget movie isn’t the ideal way to make a good movie.

On the show, producer Chris Moore often blasted Rankin and Potelle for their lack of authority on set, but Rankin still prefers to go about his business quietly, and Presmyk and Sonnier accommodate him. Sonnier sees Cinestate as an auteur-friendly outfit: He likes writer-directors and trusts them to know the material better than anyone, even if he needs to push back on them on occasion. Of his working relationship with Zahler, Sonnier says, “We have knock-down, drag-out screaming matches in the editing room, but he tells me to go fuck myself on any note.” He catches himself. “Actually, he’s a kind soul. He tells me, ‘Nope, your note is garbage and I’m not going to do it.’ And that’s it. That’s the end of the conversation.”

Balloon Fight: Take 1 is a disaster. The crew has done too good a job filling up the room with balloons, and both actresses are completely buried by them, like infants tossed in a ball pit. All that can be seen on the monitor are little waves of balloons where the women are fighting, and their precisely choreographed movements are reduced to screams, the pop of a few balloons, and five bullets released from the chamber. And so the subsequent hours are all about removing balloons without diminishing the effect, which must sustain a fight-to-the-death tension while suggesting a perversion of the most innocent of childhood delights.

After a few more takes fail to satisfy the filmmakers, Presmyk walks over to explain the obvious: No one has ever thought to shoot a fight scene in a room full of balloons, and so they’re learning some new things tonight. It’s easy to forget the context of the scene, which is about halfway through a script about a 17-year-old trying to stop a school shooting. It’s easy to forget the real-life context for the film itself, which is ongoing and politically fraught, and may create an inhospitable environment for its release. And it’s easy to forget this is only one movie among many in the Cinestate arsenal, part of a comprehensive plan to become the dominant name in low-budget genre cinema. For now, it’s just process.

They get it right on the ninth take, just after midnight. There’s an explosion of applause from cast and crew. Then it’s on to the next shot.

Scott Tobias is a freelance film and television writer from Chicago. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, NPR, Vulture, Variety, and other publications.