The 10 Best Shots From Movies in 2019

In a year defined by a mix of masters and newcomers, films from ‘The Irishman’ to ‘High Life’ to ‘Uncut Gems’ provided memorable, stunning imagesChoosing a set of shots to demonstrate the apex of filmmaking in a single year is a challenge. Not only because this year rallied in the home stretch to encompass one of the better selections of the 2010s (especially when foreign-language imports were factored in), but because the criteria are so desperately subjective. How do you showcase great work without reducing movies to easily digestible emblems? Is beauty the measure of a great shot, and if so, how often do we truly trust the eye of the beholder? Do we privilege complexity over simplicity, and can we always recognize the difference between the two? Are we talking about images that drive or otherwise define the movies they’re taken from, or is there room for memorable throwaways? Do we defer to old masters or hype up young talents, keeping in mind that some veterans, like Brian De Palma, refuse to grow up? And speaking of old masters, Martin Scorsese—who’s composed a few decent shots in his day—has said that “cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” Hopefully, you’ll agree that the 10 choices below contain multitudes.

Ash Is Purest White

“One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage,” wrote Anton Chekhov, “if it isn’t going to go off.” Early on in his epic, decades-spanning romantic drama Ash Is Purest White, Jia Zhangke sees the great Russian writer and raises him: Who needs a rifle on the stage when you can drop a pistol on the dance floor in the middle of “Y.M.C.A.”? As his career has gone on, Jia has honed his mastery of long takes to the point where they’re simultaneously sophisticated and unshowy, and the staging here is pure slapstick: Todd Phillips tried the exact same gag in Joker—“tried” being the operative word. (The Village People music cue adds the humor, but it’s also become one of Jia’s tropes after the ecstatic use of the Pet Shop Boys’ cover of “Go West” in Mountains May Depart.) That the notably shoddy, low-level gangster Bin (Liao Fan) even lets his piece slip out in the first place suggests that he isn’t exactly public enemy number one; the symbolism of a man who can’t handle his weapon is at once wickedly satirical and deeply sad. As it turns out, Bin’s lover Qiao (Zhao Tao) is the real crackshot of the couple, and it’s ultimately her decision to fulfill Chekhov’s edict—firing the gun in the middle of a deadly street brawl—that reroutes both characters’ destinies and ignites Ash’s incandescent portrait of love as something that refuses to burn out or fade away.

Atlantics

Winner of the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best First Film and Oscar-shortlisted for the Foreign-language prize, Mati Diop’s Dakar-set Atlantics is one of the year’s most accomplished features, with critics singling out Claire Mathon’s dextrous, shimmering cinematography as its most outstanding element. The film is surely beautiful, albeit in a hazy, glancing way; at times, the images are too incongruous and mysterious to register as conventionally “gorgeous,” boldly blending genres and styles in the service of a wrenching political allegory about Senegal’s social and economic stratification. Gifting his young bride-to-be, Ada (Mama Sane), a new iPhone while reclining poolside in his palatial oceanfront digs, upwardly mobile Omar (Babacar Sylla) gazes out at the sea, where his eyes meet a sculpture anchored in the water. We’re immediately cued to remember Ada’s lover Souleiman, who has disappeared during a perilous boat journey to Europe. The ghostly superimposition puts a (stylized) human face on the refugees who’ve lost their lives fleeing a country of limited options and confirms Diop’s status as a formidable image-maker.

Domino

Brian De Palma is the supreme split-screen filmmaker of all time. Think of the prom scene in Carrie, or the doubling techniques in Dressed to Kill, or the boxing match in Snake Eyes; his ability to choreograph parallel action while subdividing the frame into different planes of perspective and meaning has always verged on authentic genius. Nobody wanted to give De Palma’s new, more-or-less direct-to-VOD thriller Domino credit as an auteur work, but the fact is that at least three or four of its sequences have the verve and invention of the director’s glory days, including the spectacular—and spectacularly incorrect—set piece depicting a terrorist attack on a European film festival, broadcast on a social media feed that shows the killer’s face side-by-side with the victims glimpsed through her weapon’s high-tech crosshairs. The result of De Palma’s visual gamesmanship is a multifaceted massacre scene that could just as easily be filed under exploitation as critique; by conflating different kinds of “shooting” (the camera and the gun) and reflecting the murderer’s gaze back at us twice over, Domino forces us to think about what we’re looking at instead of simply consuming it (even as the villains’ plans are explicitly to transform political violence into online entertainment). Long after many of 2019’s more conventionally lauded movies have faded from memory, De Palma’s unapologetic virtuosity will endure.

High Life

On the left, a video screen shows a shot from Edward S. Curtis’s silent, fictionalized ethnographic adventure film The Land of the Head Hunters, shot in 1914 and depicting ancient myth; on the right, at the edge of the galaxy and the end of history, Robert Pattinson comes in from the cold of deep space and doffs his suit. And in the middle, caught between a nostalgically false past and a bleak sci-fi future, a little girl watches—she is the audience, and we are her. Critics snickering over the many bodily fluids spilled during Claire Denis’s astonishing (and, yes, messy) High Life missed (or downplayed) how formally ingenious so much of its storytelling is and how masterfully the movie plays with time—compressing and elongating, doubling back but never reversing. Denis juxtaposes individual life cycles with larger cultural and technological endeavors and, as is her specialty, defaults to biology as the only reality we have. Our bodies don’t betray us so much as we expect too much from them; where a filmmaker like Stanley Kubrick argued once upon a millennium for transcendence, Denis has no illusions about where we go when we all fall asleep.

The Irishman

I wrote already about the significance of doors in Martin Scorsese’s depressive masterwork, but it can’t be overstated just how powerfully The Irishman’s finale imparts a sense of closure. It doesn’t just feel like the end of the movie, but a reckoning with an entire genre. If there’s something universal about the fear of loneliness—about being the last one left to turn out the lights—the application of that isolation to a history of gangster films sensationalizing (and glamorizing) honor among thieves can’t help but come off as a gauntlet dropping, especially considering who’s behind the camera. In Raging Bull, Goodfellas, and The Wolf of Wall Street, Scorsese ended with his antiheroes addressing the camera; here, the fourth wall remains up, cutting us off once and for all without the playful, reassuring reminder that it’s all a movie. Frank not wanting the door to close but being powerless to do anything about it is as real as it gets.

Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood

1. It’s the law to remind anybody who watches Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood that Brad Pitt is 55 years old in it, and it’s also the law that you have to be amazed by that fact. You can’t just shrug and say, “Whatever, lots of people look after their bodies, he’s not special.” It’s objectively insane that he looks like this, sorry.

2. In addition to its obvious function in mythologizing Pitt’s stuntman Cliff Booth—looking perfectly low-key even at a high altitude, a Serious Man if ever there was one—the shot represents one of Quentin Tarantino’s greatest head fakes. We know that the house next door, looming in the background, belongs to Sharon Tate, whose real-life fate hangs over all the fictional hang-outs in the movie; we wonder whether, while Cliff is fixing Rick’s roof, he’s going to lock eyes with the beautiful Mrs. Polanski and start rewriting history. But he doesn’t: Cliff stays in his lane, and while he does end up having a hand in Tate’s fate, they’re the only two major characters in the movie who never actually meet. So close, yet so far …

Parasite

It’s too much to call Parasite a horror movie, but its most memorable image is of a “ghost”—or at least that’s what the youngest member of the Park family thinks he’s seeing during a midnight trip to raid the family fridge. The revelation of what (or who) the boy is actually seeing is at the heart of Bong Joon-ho’s multi-tiered screwball thriller, which pivots on the eternal paranoia of the monied classes that somebody is coming from behind (or beneath) them to grab what’s theirs; the “ghost” is actually a spectre of an all-too-human condition. Take the movie apart, and the idea that a rich kid’s ongoing psychic torment derives from accidentally catching sight of the help at an inopportune moment feels like its secret beating comedic heart—it’s the most vivid and viciously funny of Bong’s symbols. That said, there are a half-dozen other shots from Parasite that could qualify for this position. Nobody composes more brilliant frames these days than Bong, who’s hopefully on his way to an Oscar nomination.

The Souvenir

Joanna Hogg conjures up the memory of her countryman Nicolas Roeg with this brilliant tripartite wide shot, which captures the film’s two lovers during a fraught holiday: Don’t Look Now, but they’re in Venice, where all romance goes to drown. The visual tripling of Tom Burke’s Anthony alludes to a dangerously changeable personality that Julie (Honor Swinton Byrne) just can’t disconnect from, no matter how many reasons his behavior gives her; he’s all things to her, good and bad. For most of the movie’s duration, she’s trapped in his thrall, tending to his addiction even as hers (to him) grows deeper. Hogg’s always been an adept formalist, but The Souvenir’s darkly romantic autobiographical tinge resulted in something like a mainstream breakthrough.

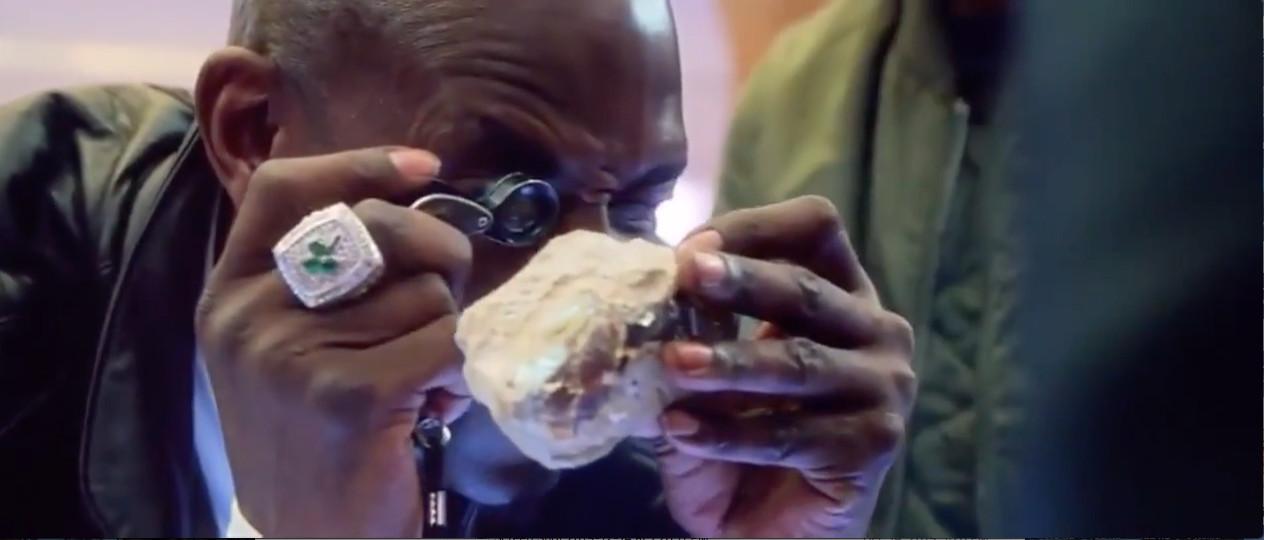

Uncut Gems

The Safdie brothers don’t necessarily care about perfect shots: Their style is frenetic, with the camera either chasing the characters or else crammed in their faces. Uncut Gems is no exception, but it’s still got its share of killer images, like this close-up of Kevin Garnett looking at the Ethiopian opal being fenced by Adam Sandler’s manic high-end jeweler Howard Ratner. Between the mystical imported stone and KG’s bespoke 2008 championship ring, there’s as much bling per inch as anybody could want; what’s funny, though, is the clinical, intimate intensity of the Big Ticket’s gaze. In the moment he’s just another covetous customer in Howard’s cramped shop, not quite believing his eyes.

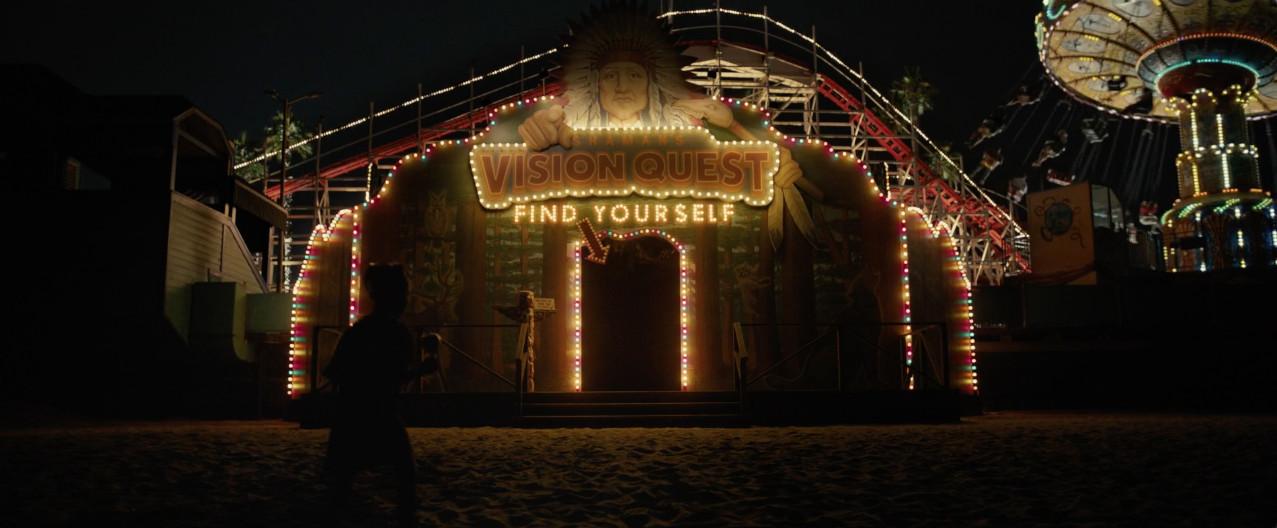

Us

Of all the ’80s classics referenced in Jordan Peele’s strenuously postmodern Us, nobody really mentioned Big, but the “Vision Quest” attraction visited by young Adelaide in the film’s superbly spooky prologue evokes the fortune-telling Zoltar machine that turned Tom Hanks from a boy to a man. Adelaide is similarly on the verge, but maturity isn’t quite what fate has in mind. The written invitation to “Find Yourself” anticipates the identity-crisis themes of a movie that, while too layered and complicated for its own good, attempted to diagnose divisions in American life on multiple fronts, an ambitious effort featuring its share of eloquently realized visuals (the Native American iconography is suggestive in a movie positing an occluded national population). Here, Peele’s fundamentally fable-like sensibility is outlined in perfectly ominous neon—the threshold of a carnivalesque nightmare whose impossible promises of self-actualization are fated to come true.