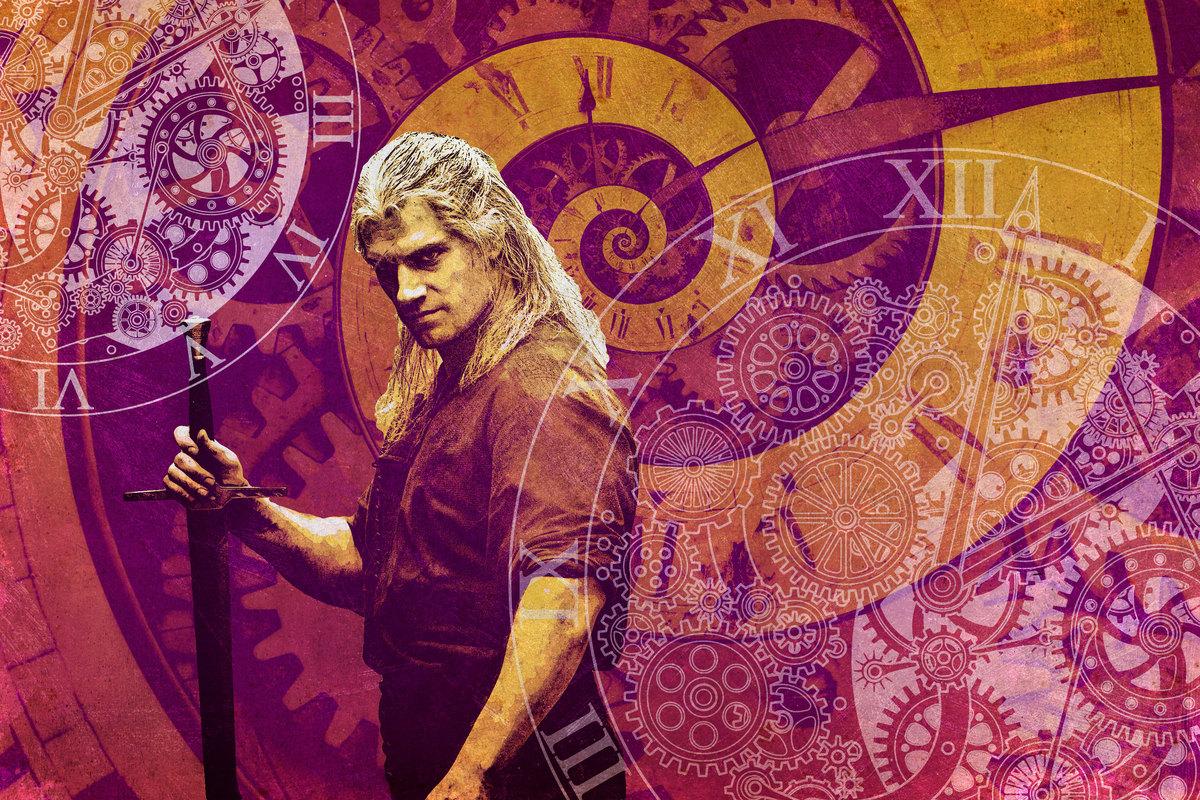

I first reacted to the strikingly epic poster for Netflix’s latest weird TV show, The Witcher, by crying out, “What the hell is that?” to no one in particular. A few days before its release, I had somehow never heard of this series, based on video games that were themselves interpretations of short stories by Polish fantasy writer Andrzej Sapkowski. “No way,” I blurted out when finding out that Henry Cavill, Superman himself, was the guy with long blond hair standing in the middle of said poster, a fierce look of defensiveness and incalculable sadness in his eyes. “Geralt!” I simply repeated, as IMDb informed me of this mysterious hero’s name. The Witcher didn’t seem real, yet each and every strange detail about it compelled me to know more. And soon I realized how the bizarreness of the show was essential to its functioning. There is method in the madness.

The first scene of the first episode of The Witcher shows our hero, Geralt of Rivia, fighting and killing a giant and terrifying spider (a “kikimora”) in a forest, with nothing but a sword and his massive arms. Despite his courage and service to society (a witcher is a monster hunter who undergoes mutations as a child that make him extremely strong and durable and able to live for centuries), however, the triumphant Geralt is then treated like a pariah by the citizens of Blaviken, the village where he has ended up. It soon becomes clear that witchers and other “monsters” are often met with skepticism in this world. Although the show itself establishes that monsters do exist and are too dangerous for regular mortals to defeat, many characters in The Witcher either doubt their existence or question the powers of witchers, seeing Geralt as an opportunist taking advantage of people’s irrational fears to earn his coin. That’s why Geralt spends half his time grunting and rolling his eyes: He’s used to his benefactors doubting his own importance, if not his very existence.

But what makes The Witcher more bizarre and folkloric than a typical fantasy story using monsters and mutants as metaphors for persecuted minorities is how it complicates the significance of its mythical creatures. In the pilot episode, Geralt is asked by Stregobor (Lars Mikkelsen, Mads’s brother), an old and important man, to kill Renfri (the excellent Emma Appleton), a young woman who he claims is a very bad omen for Blaviken. But Renfri argues back: Stregobor has made her life hell simply because she happened to be born during an eclipse. Geralt is no longer sure what to believe—he is placed in an uncertain frame of mind, just like the spectators living in the real world who know that monsters definitely aren’t real. Later, Geralt will claim that golden dragons do not exist, only to be proved wrong. Even the monster slayer doesn’t quite know the bounds of his own reality.

The Witcher starts from a secure place, with Geralt as the one individual able to tell the real from the imagined, and progressively blurs these clear lines for both its hero and the audience. Crucially, and together with this muddying of reality, is the increasingly confusing chronology of the show (before it all falls into place, in the last couple of episodes); as parallel narratives are introduced, time itself loses its clear boundaries. Ciri (Freya Allan) is the young princess of Cintra, a kingdom under attack from the enemy empire Nilfgaard, who is told by her dying grandmother, the queen, that she must find Geralt of Rivia, her “destiny.” Upon her death, Renfri murmurs similarly mysterious words to Geralt: “The girl in the woods will be with you always; she is your destiny.” It seems as though Ciri and Geralt are operating in the same time frame and must simply find each other, but Renfri’s message already suggests something more complex—and mythical. It was in a forest that Renfri asked Geralt to side with her, so she may be referring to herself with the words “the girl in the woods,” but her talk of “destiny” complicates this simple interpretation. With these last words, Renfri collapses Geralt’s past into his future, and indicates, however opaquely, that Geralt’s path will surprise him. It sounds like a curse, a prediction—or an everlasting truth.

Many spectators have declared on social media that they simply didn’t get why any of the events in The Witcher were happening: Unlike conventional TV shows (or any narrative art), the more of the show you watch, the less you understand. The individual stories do progress and make sense on their own, but it is their links to each other that perplex because they seem to loosen, not tighten, with each episode. It soon becomes clear that Geralt’s life is passing at an unnatural speed: From one episode to the next, we learn that a king has died. Or Geralt bumps into Yennefer (Anya Chalotra), a mage he has fallen for and who, like him, doesn’t age; they talk about their last meeting a few decades prior. Meanwhile (or should we say later-while?), Ciri is making her way through war-torn villages, guided only by her survival instinct and strange visions, progressing at a normal pace. One begins to grasp that these two characters cannot be connected by conventional generational, or even time-based ties; what links them is much more ethereal, timeless, and just a bit beyond human understanding: It is a myth.

By scrambling both its own mythology and its sense of time, in addition to having incredibly surreal yet vivid and violent images of monsters and mages in action, The Witcher makes visible the workings of myths themselves: It is their surreal nature and their freedom from time that makes them so potent, and, ironically, so enduring. Their lack of definition and their free-floating essence are captivating because they let our imagination flow, filling in their many gaps without ever arriving at a certain complete picture; they can always be rethought. Like Robert Eggers’s 2015 film The VVitch (and, in a way, his recent film The Lighthouse, about nautical myths), The Witcher exposes how our doubts regarding myths are what keeps them alive. Having the characters use contemporary language and insults (a lot of “fucks” and “shits” are said), and giving Geralt a bard to follow him around and write factually incorrect but epic songs about his exploits, reinforces this idea that legends, precisely because they are imprecise, not bound to a specific time, and wildly unrealistic, are able to travel through decades and impact many lives.

Geralt eventually learns that he is tied to Ciri by the Law of Surprise, a maybe-mystical pact he thoughtlessly agreed to years before the girl was even born, which gave him the right to her, and thus the responsibility to protect her were she to come into danger. The intricacies and realities of the rule are, at first, hard to grasp for regular mortals like you and me, living in linear times when such promises are not the typical way to do business, but the show does a fairly good job at explaining it without demystifying it. The connection between Geralt and Ciri goes from being confusing to seeming both out of their control and necessary, even if they both have to fight for their own reunion. In a way, the idea of “destiny” is at the core of any narrative, be it traditionally constructed or convoluted: The point is to get from A to B, whether your character and audience are aware of it or not. This is also how myths function, as they are perpetually present and guide our thinking even if we question their veracity.

Whether a Netflix TV show is the best medium for the analysis of myth-making isn’t certain; I wouldn’t blame anyone for giving up on The Witcher after a few barely comprehensible episodes featuring countless characters and places with increasingly perplexing names (my favorite is, without a doubt, “Mousesack”). Yet the combination of campy visuals (these pants are as tight on Geralt as the killings are gruesome) and scrambled structure that an episodic, televisual format allows makes for a striking viewing experience, and one that takes myths into our contemporary era in a new way. Bards and word of mouth have been replaced by social media and TV series, and the legends will live on.

Manuela Lazic is a French writer based in London who primarily covers film.