One month into Lonzo Ball’s NBA career, back when 2017’s no. 2 pick played for the LeBron-less Lakers, The Jump ran a segment on Ball’s suspiciously awarded home-court assists. The ESPN show displayed a series of plays at Staples Center in which Ball received an assist despite playing little role in the Lakers’ eventual bucket. In one such play, for instance, he kicked out to Kyle Kuzma, who didn’t score until first pump-faking, taking two dribbles, and bouncing off a defender near the rim.

“This has been happening. He’s been getting inflated assists,” Jump cohost Brian Windhorst railed. “He had an earlier game this year where he had four questionable assists, and the NBA left it alone. If the NBA leaves this alone, I’m calling for an investigation.”

For decades, though, Ball wouldn’t have been alone with this home-court generosity. From 1983-84 (the first season that Basketball-Reference splits stats by location) through the start of this season, 278 NBA players recorded at least 2,000 total assists. A whopping 256 of those players—92 percent—recorded a higher per-game assist average at home than on the road. On average, the group received about 10 percent more assists from friendly home scorekeepers.

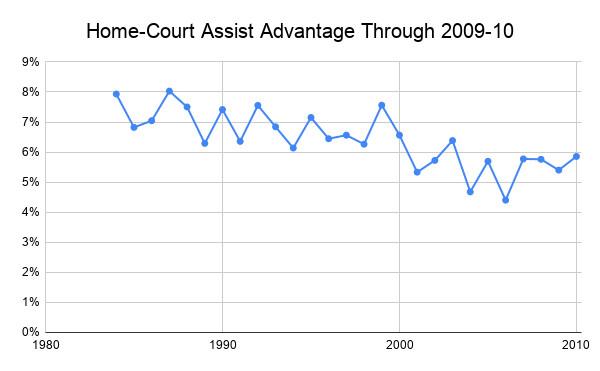

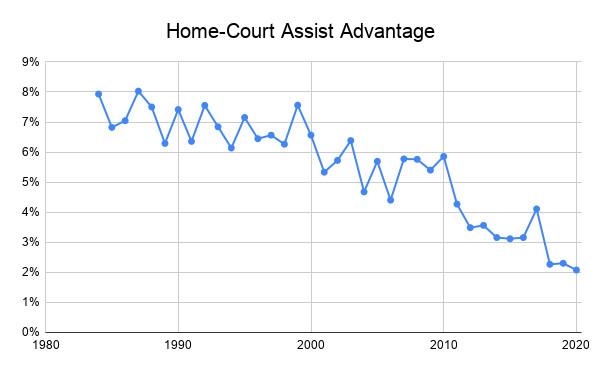

This pattern persisted on a team level, as well. Even adjusting for the fact that teams tend to score more points at home, they also tended to accrue larger-than-expected assist totals. The average team’s assist percentage (the proportion of made shots preceded by an assist) was 5 to 8 percent higher at home for decades, and the judged criteria for an assist could vary widely from arena to arena.

But a shift occurred over the past decade and accelerated in the past three years—timing, coincidentally, with Ball’s entrance to the league. The former Laker and current Pelican might have enjoyed mockable home cooking on occasion, but zoom out to survey his full data set, and a new picture emerges.

Ball’s per-game assist average was higher on the road than at home in his two seasons with the Lakers. In fact, his assist percentage has been higher on the road every season of his career.

Lonzo Ball’s Assists Splits

Once again, Ball isn’t unique in this phenomenon. Across the league, the home-court assist advantage—a consistent analytical assumption for decades, a staple of NBA scorekeeping—has all but disappeared.

The assist is not as simple or stable as it appears. By way of comparison, NBA Advanced Stats tracks “potential assists,” which it defines as “any pass to a teammate who shoots within 1 dribble of receiving the ball.” (Because this stat looks at “potential” rewards, it doesn’t care whether the shooter actually makes his attempt.) This calculation is a strict and automated process with no definitional leeway.

Actual assists are a different story, however. They are awarded by the scorekeepers in each arena, and they are more vaguely defined, as simply passes “that lead directly to a made basket.” This instruction leaves ample room for interpretation; as The Wall Street Journal noted in a 2009 story about assist bias, “There are no details about how many steps shooters can take after receiving a pass; nothing about shot-fakes, head-fakes or pivot moves and no hard guidelines on how much time can elapse between the pass and the shot.”

Assists are a judgment call, and natural human tendency pushes scorekeepers to be more generous to their own players. Writing for Nylon Calculus in 2015, Seth Partnow noted that when a player shot within half a second of receiving the ball, the passer was awarded an assist the same amount both at home and on the road. But with a made shot that came one second after a pass, and 1.5 seconds, and two seconds, and so on, scorekeepers were more likely to give an assist to a home player than a visitor.

Yet much like post-up plays and low-scoring games, this bias seems to be decreasing, or leaving the league entirely. Let’s reexamine the earlier graph with the most recent decade added. For most of the 2010s, the home-court assist advantage declined a bit, to the 3 to 4 percent range. But the past three seasons have seen an even starker decline, to 2 percent—less than half of what the previous low had been.

It turns out there’s an explanation for at least the most recent dip. According to an NBA spokesperson, beginning with the 2017-18 season, the league added a stats auditor to watch games at the replay center in Secaucus, New Jersey. Using a DVR-style device to review plays during breaks in action, this individual can serve as a fallback option in the case of a misawarded number in the box score. All decisions are made by the in-arena stats crews, the NBA official stressed, but the auditor can work in conjunction with them and recommend certain changes as the game speeds by. The more eyes, the official said, the better.

The auditor wasn’t installed specifically with the assist bias in mind, but the secondary layer seems to have affected this area most acutely. The NBA might have let a few of Ball’s generous assists stand, but behind the scenes, it has evidently worked to close some of the more egregious loopholes.

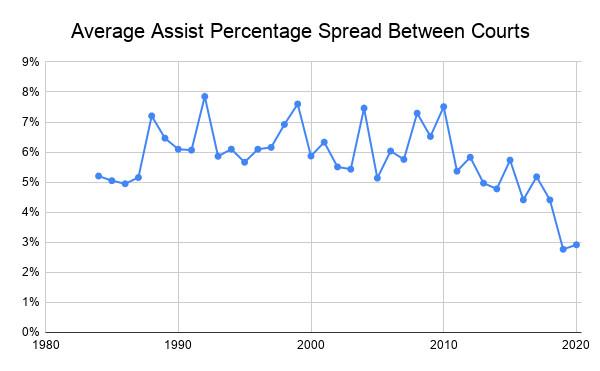

Due in part to this change, the spread between assist decisions across arenas has also shrunk in recent seasons. Looking at both the home and road teams’ assist percentages together, assist percentages are more uniform across the league now than they have ever been before, when an assist in, say, Cleveland could go unawarded in Miami. As with home-court bias, interarena assist disparities have also diminished to their lowest level on record.

These changes are subtle, of course, and shouldn’t make too much of a difference to fans or analysts. The top passers are still by and large the top passers; while individual game totals might vary widely, it’s not as if anybody’s season-long average is going to shift much with these biases evened out.

But the changes matter for a few reasons. First, they can influence a comparison between two players or a chart of an individual career trajectory. When LeBron James moved to the Heat, for instance, his assist numbers declined. Was that because he was passing less, or worse, in Miami? Maybe. But also, the turn-of-the-2010s Cavaliers were one of the league’s most generous assist givers, while the Heat were one of the stingiest. Adjusting for home court (much like baseball analysts do for home run hitters in the thin air of Coors Field) places James’s worse-on-the-surface assist numbers in Miami on par with his inflated Cleveland efforts. (LeBron’s place on the career assist list probably took a slight hit in his four seasons in Miami, but he also benefited from 11 seasons with Cleveland’s friendlier scorekeepers.)

Or, remember that almost every prominent passer in NBA history collected more assists at home than on the road? One of the few exceptions is Steve Nash, who recorded 0.4 more assists per game on the road than at home. In Nash’s heyday, Phoenix employed one of the least-friendly scorekeeping crews for assists. Had he enjoyed a typical home bias over his career, he would have retired with upwards of 500 more career assists than he did, and he would move ahead of Jason Kidd (who enjoyed a typical 11 percent home-court assist advantage in his career) for eighth on the all-time assists-per-game leaderboard.

With a reduction in home-court and between-arena assist disparities, these sorts of skews should no longer exert as much influence on a player’s numbers.

Nor should they exert as much influence in an entirely separate area of the sport—fantasy and gambling. As Matthew van Bommel and Luke Bornn (both now Kings employees) illustrated in a 2017 paper titled “Adjusting for Scorekeeper Bias in NBA Box Scores,” shrewd daily fantasy players could benefit from targeting passers in specific arenas with an extreme assist bias. The reduction in between-arena bias since that paper could limit some of these gains. And with the growing legalization of sports betting across the country, evening out assist decisions across the league would prevent sharps from pinpointing specific places to cast assist over/under bets.

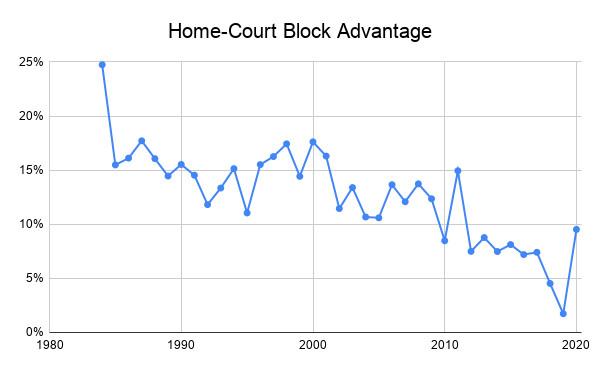

The NBA’s auditor system, to be clear, is not a complete panacea for inherent scorekeeper bias. Besides assists, blocks have historically been the easiest stat for home scorekeepers to fudge. And while home-court block bias had fallen to almost zero after the introduction of the auditor in Secaucus, it’s rocketed back up so far this season. (To account for the greater number of missed shots for road teams, this chart uses a form of block percentage, measuring the number of blocks per missed 2-point shot and then comparing home vs. road rates. An identical pattern appears with the simpler blocks per game stat.)

Barring a more specific definition, there will always be some variation in how scorekeepers measure assists. But in a league that for decades saw some of its staple statistics influenced by either intentional or unintentional meddling from scorekeepers, it seems that judgments are now being compressed and pushed toward a more uniform ruling. It’s a fair and positive development for the sport. There are more than enough officiating decisions to upset fans and spark conversation, anyway.

Stats current through Sunday’s games.