Peering through an airplane window at the frozen tundra of Chicago, Rick Welts felt a wave of panic sweep over him. His flight from New York City had just touched down at O’Hare International Airport when he heard the pilot announce that the temperature outside had plunged to 22 degrees below zero.

It was the first week of February 1988, days before the start of NBA All-Star Weekend. As the NBA’s chief marketing officer, Welts bore primary responsibility for the success or failure of the relatively new event heralded as basketball’s Super Bowl. By that year, the midseason affair had become the most critical promotional platform for a league that earlier in the decade had been beset by financial instability, widespread drug use, and a poor public image but was finally beginning to take flight as a major cultural force.

“This was the fifth All-Star Weekend, and it definitely was at a different level than those that had come before,” says Welts, now the president and chief operating officer of the Golden State Warriors. “We were on the home court of Michael Jordan, the player who would become our most popular player ever, at the beginning of his ascendancy.”

But with the host city firmly in the grip of extreme arctic cold, the logistics became complicated. The wind chill index was predicted to drop that weekend to as low as 60 degrees below zero, and Chicago Stadium, built in 1929, had neither restaurants on site where VIPs could dine nor space to accommodate workstations for the 693 members of the press. So the league decided to erect a tent outside for food service and relegated the media to rented trailers in the parking lot. Each was warmed, ineffectively, by kerosene heaters. “I’m thinking, these media guys are going to freeze their asses off—and they did!” says Brian McIntyre, then the NBA’s director of public relations. “Guys were typing postgame with gloves on.”

“That was my focus pretty much the whole weekend,” Welts says. “Make sure no one freezes to death.”

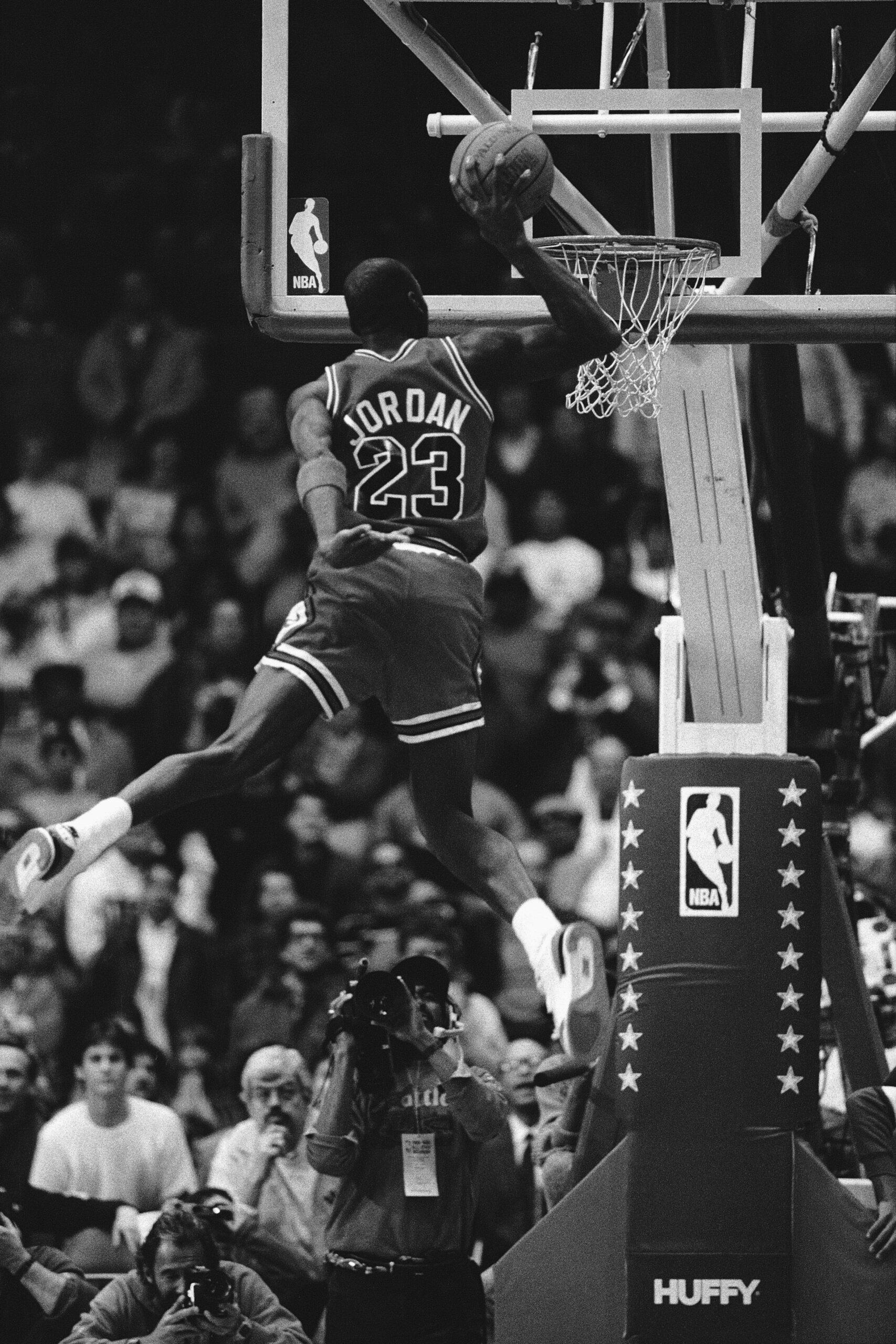

In spite of the inclement weather, the weekend amounted to a coming-out party for 24-year-old Jordan midway through his breakout season. The eventual All-Star Game MVP took off from the free throw line in the slam dunk contest and effectively launched into the NBA firmament as “the star of stars,” confirming that the once-troubled league would ascend to untold heights over the next decade on the shoulders of such an exceptional (and exceptionally marketable) talent. The event proved to be a wellspring of classic moments, from Larry Bird jabbing a finger in the air as he sank the final ball to win his third consecutive 3-point contest (then known as the “long-distance shootout”) to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar sky-hooking his way to the all-time All-Star scoring record (since bested by LeBron James). And behind the scenes, a battle unfolded that would shift the balance of power in the NBA, as some of the biggest stars hatched an ambitious plan to secure unrestricted free agency—among the critical early moves that would result in the player-empowered league of today.

The memories of those eventful few days 32 years ago loom large once again as the league’s galaxy of superstars returns to Chicago this weekend for the first time since that frigid February in 1988.

“Outside the arena, things were not so good,” Welts recalls. “But inside the arena, everything was pretty much perfect.”

As Welts fretted about Chicago’s potentially lethal subzero temps, his boss, NBA commissioner David Stern, turned his attention to a storm brewing among the players that would have monumental implications for the league’s future.

The collective bargaining agreement between the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and the league had expired in June 1987. When negotiations on a new deal began, the players had made it clear they wanted to detach themselves from team owners, to have more say in where they played and how much money they would make. Toward that end, the union proposed eliminating the college draft, the salary cap, and the right-of-first-refusal rule, which allowed an owner to hang on to a player whose contract was ending simply by matching an opposing team’s offer.

“As players, we wanted to have freedom to grow our brands, to help grow the league, and to benefit from that growth,” says Dominique Wilkins, an ’88 All-Star and slam dunk contest runner-up.

That was my focus pretty much the whole weekend. Make sure no one freezes to death.Rick Welts, president and chief operating officer of the Golden State Warriors

By mid-September, with the season on the horizon, negotiations reached an impasse. The union responded by filing an antitrust lawsuit against the NBA, but a judge ruled in December that the league was protected from antitrust claims because of its collective bargaining relationship with the players association, sending the union back to the drawing board. In late January, in the midst of a lengthy NBPA staff meeting, attorney Jim Quinn was struck by a wild notion. “I finally looked up with an idea,” he recounts in his recently published book, Don’t Be Afraid to Win: How Free Agency Changed Pro Sports. “‘What if we weren’t a labor union anymore? If there’s no labor union, how could there be a labor defense?’” The union set a meeting for All-Star Weekend in Chicago to discuss.

On All-Star Friday, February 5, 1988, more than 40 players gathered in a ballroom at the Hyatt Regency. The player representatives from each NBA team were joined by most of the All-Star squads, including Abdul-Jabbar, Bird, Jordan, and Magic Johnson. The union counsel made its case for decertification. “The situation was tense,” Quinn wrote. “Everyone in the room was anxious.”

“There were grumblings of a strike of either the All-Star activities or the NBA playoffs,” says Charles Grantham, then NBPA executive vice president. “But it was not likely to happen. A work stoppage negatively impacts players, because while they’re losing money their skills are also depreciating.”

There was also concern that a strike might negatively affect the NBA’s surging popularity. “In 1988 we had hit our stride,” Welts says. “The whole league was going through an amazing growth period by every measure. The business was exploding. Our players were looked at completely differently than 10 years before. Sponsors were interested in signing up with the NBA that had never been interested in our sport before. We were right at that moment in ’88 where people were starting to say, ‘Whoa, this is not the league that Stern inherited in 1984.’”

But along with all that growth came growing pains, ergo the roiling unrest at the union meeting. Eventually, NBPA president Junior Bridgeman spoke up in favor of decertification, persuading the player reps to vote unanimously to move forward with a vote of all 276 NBA players.

Once the meeting adjourned, NBPA executive director Larry Fleisher informed the media of the decertification plan. “Yes, it’s extreme,” Fleisher told reporters. “But maybe now [the team owners] will finally stop sitting back in their own little cocoons thinking that the players are going to cave.”

“That actually was the beginning of the modern player-empowerment movement,” says Bob Sakamoto, then a Chicago Tribune Bulls beat reporter who covered the ’88 All-Star Weekend and the decertification effort. “It went hand in hand with the NBA philosophy of star power, of David Stern’s strategy to turn the NBA around by promoting the biggest stars and making people want to watch NBA games—not because you follow a certain team, but because you want to watch a certain player. The players association realized that Stern’s strategy gave the players an opening to say, ‘If you’re hanging the health of the league on our star power, we want certain freedoms.’”

On the morning of All-Star Saturday, Stern gave his first public comments on the decertification movement. “We’re not going to accept the invitation to chaos,” he told the assembled media.

The union viewed Stern’s response as a win. “What he saw was exactly what we intended,” Grantham says. “At that moment, everything was orderly. But he knew if the union decertified, it would be chaotic. A team would have to negotiate a separate contract—including terms and conditions of employment, benefits, and all the other things a union provides—with each individual player.” Agent Bob Wolff told the Chicago Sun-Times, “It means that I could go in with Larry Bird and say, ‘I want $3,000 a day per diem. I want a limousine to pick Larry up. I want two king-size beds for him on the road.’”

By March, the NBPA had collected votes from all the teams. The result, according to Quinn, was “a landslide in favor of decertification.” The maneuver worked just as the union had hoped, compelling the owners to return to the bargaining table to negotiate in good faith.

Finalized in April, the new six-year CBA ushered unrestricted free agency into the NBA, allowing any player with seven or more years’ experience and whose second contract had expired to decide where he would play. The CBA also reduced the draft from seven rounds to three in ’88 and the now-standard two in ’89. Tom Chambers, who left Seattle and signed with Phoenix in July ’88, became the league’s first unrestricted free agent.

“A lot of the freedoms that NBA players enjoy today, these are things that the union was fighting for at the ’88 All-Star Weekend,” says Isiah Thomas, an All-Star and NBPA vice president during the negotiations. “We always fought for the next generation coming. You never thought about just yourself.”

While the 2020 All-Star Weekend will honor the lives of NBA legend Kobe Bryant and his daughter Gianna, a comparatively modest tribute to a Hall of Famer gone far too soon kicked off All-Star Saturday in ’88. (At that point, All-Star Friday was for invite-only parties.) A few weeks before, “Pistol” Pete Maravich had died at the age of 40 after suffering a heart attack during a pick-up basketball game. Instead of a traditional moment of silence, the capacity Chicago Stadium crowd stood and cheered for the five-time All-Star. In the game the next day, first-time All-Star Karl Malone wore no. 7 in a salute to Maravich’s long tenure with the Jazz.

First up on the day was the Legends Game, which Welts had made a part of All-Star Weekend after seeing 75-year-old baseball Hall of Famer Luke Appling hit a home run in the 1982 MLB old-timers game. The NBA ended the tradition after All-Star ’93. “I hadn’t been smart enough to think about what a basketball old-timer’s game would look like compared to a baseball old-timer’s game,” Welts says with a chuckle. “Watching our heroes out there playing basketball in their 50s didn’t do justice to their careers.”

Do I think I won? Yes! Does Michael think he won? Yes! I say I lost the contest just because he was at home.Dominique Wilkins, ’88 All-Star and slam dunk contest runner-up

Taking the floor were such retired NBA luminaries as Rick Barry, John Havlicek, Oscar Robertson, and Jerry Sloan. Then–Bulls head coach Doug Collins, playing for the West team at the relatively young age of 36, drained a 3-pointer with 33 seconds remaining in regulation, sending the game into sudden-death overtime. Bob Cousy, coach of the winning East squad, quipped, “We’re confusing [the West] with speed, quickness—and a little youth. We don’t have too much of it, but we’re utilizing it.”

In the long-distance shootout, Larry Bird famously wore his warm-up jacket—a subtler form of braggadocio than he displayed two years earlier, during the ’86 All-Star Weekend in Dallas, when he walked into the locker room and was heard saying to his opponents, “Which one of you guys is going to finish in second?” In Chicago, Bird edged out Seattle’s Dale Ellis, punctuating his third straight victory in the contest by raising an index finger to the sky before the go-ahead ball splashed through the net.

But even as Larry’s legend grew, the day—and perhaps the entire weekend—belonged to Michael Jordan. While Jordan, then in his fourth NBA season, would have to take his lumps for a few more years before hoisting a championship trophy, All-Star Weekend in Chicago caught the league’s most dazzling arriviste in the middle of his breakout. “It’s hard for people, particularly younger people, to understand that in 1988, Michael wasn’t yet a big dog,” Thomas says. “In the ’80s, the champions ran the NBA. It was the Celtics, the Lakers, the Sixers, and soon the Pistons. The league up to that point had been all about Dr. J, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Moses Malone, Larry Bird, Magic Johnson. Jordan had been an All-Star, yes, but he hadn’t won anything.” At season’s end, Jordan would collect his first of five MVP awards and become the first—and so far only—player in NBA history to win both the scoring title and Defensive Player of the Year.

In All-Star Saturday’s highly anticipated main event, Jordan defended his dunk contest title against Wilkins, the sixth-year veteran and formidable ’85 champ, who lived up to his nickname, “the Human Highlight Film.” The all-time classic duel was, however, not without controversy, as ’Nique and others later alleged that Jordan benefited from homerism on the part of the judges, a panel that included Chicago-born retired NBA player Tom Hawkins and Hall of Fame Chicago Bears running back Gale Sayers.

During the three-dunk final, Wilkins garnered a perfect 50 score on each of his first two dunks. Jordan received a 50 on his first jam—and a 47 on his second, prompting boos to rain down from the stands. “These judges are going to need the National Guard to get out of Chicago Stadium!” TBS’s Bob Neal remarked on the broadcast.

With Jordan trailing 100-97 going into the last dunk for each player, Wilkins delivered a stunning two-handed windmill that the judges appraised with a meager 45. “I was shocked,” Jordan said afterward of the low score. Asked if he believed Wilkins was robbed, Spud Webb, Wilkins’s Atlanta teammate and an ’88 dunk contest participant, remarked, “Dominique should definitely go in the locker room and check to see if he’s still got his wallet.”

That left the hometown hero an opening for a grand finale. “I looked up into the box seats and came across the guy who started it all, Dr. J,” Jordan later told the press, alluding to the jam Julius Erving popularized at the 1976 ABA dunk contest. “He told me to go back all the way, go the length of the floor, then take off from the free throw line.” Jordan needed two tries to put the ball through the rim, but the dunk earned him a 50 and victory in a showdown that has endured.

“The fact that we’re still talking about that slam dunk contest 30-plus years later—you know it was the greatest of all time,” Wilkins says now. “Do I think I won? Yes! Does Michael think he won? Yes! I say I lost the contest just because he was at home.”

A pair of famous photographs would help elevate Jordan’s free throw line dunk to immortal status: a view from beneath the basket by Sports Illustrated’s Walter Iooss Jr. and a sideline shot by Bulls team photographer Bill Smith. Rendered on posters, those two images graced the bedroom walls of countless children of the 1980s and ’90s, including some NBA-bound ballers.

The final passing of the torch from one generation of the NBA to the next was Jordan replicating Dr. J’s dunk. The league had finally taken off.Isiah Thomas, NBA All-Star and former NBPA vice president

Smith had seen Jordan practice the free throw line dunk and believed the profile would be the most dramatic angle. “I thought, the shot’s gotta be midflight, capturing the distance and the height, the immense space between the free throw line and the basket, between his feet and the ground,” he recalls. “I had to pick him up with pinpoint focus in a split second to catch him in midair. I remember thinking, ‘I hope I don’t screw this up.’” Smith dropped his film off at an all-night processing lab several blocks from Chicago Stadium. “I worried about it all night long and could hardly sleep: Was the shot crooked? Did Michael blink? Would the lab have a light leak in their system? A lot could go wrong. I came back the next morning, right when they opened. I went through all the rolls of film, like, Where’s the Michael shot? When I saw it, it was just a moment of exhilaration and relief. I’d nailed it: the determined look on his face, the ball cocked back in his hand. In the background, you could see the anticipation, the crowd and the other contestants holding their breath as he was floating.”

Nike wanted Smith’s photo for a poster and offered him a pittance to buy it outright. He wisely chose to hang on to the copyright, asking instead for a single-use licensing fee. He has since licensed the photo thousands of times, for T-shirts and trading cards and countless other memorabilia. “I’d see it everywhere,” the photographer says. “I was on vacation a couple of years later in Bangkok, and I came upon a tiny sporting goods store that was closed. And in the window, they had the Nike poster. I was like, wow, I’m 12,000 miles from Chicago and there’s my photo! That one shot brought me notoriety I hadn’t known before. People started introducing me as ‘Bill, the Bulls photographer that took that famous Jordan picture.’”

To NBA players and executives, Jordan’s flight from the charity stripe was the moment when he became the NBA’s torch bearer for at least the next decade.

“There were two big leaps for the NBA in the 1980s,” Welts says. “The first was Magic and Bird, their rivalry kindling the potential that we believed was there for the league even when it was in trouble. We were right in the middle of the second leap, literally, when we were in Chicago at the All-Star Weekend in 1988. Michael changed the trajectory for the league.”

“The final passing of the torch from one generation of the NBA to the next was Jordan replicating Dr. J’s dunk,” Isiah Thomas says. “The league had finally taken off.”

On Saturday night, the All-Stars convened at the Chicago Theatre for the NBA gala, featuring singer Al Jarreau, who would perform the national anthem before the next day’s game, and stand-up comedy from Doritos spokesman Jay Leno. The problem: Leno knew next to nothing about basketball. So the NBA tapped Joe O’Neal, then a Bulls front-office peon turned All-Star Weekend gofer, to school him. “Offense, defense—he didn’t have a clue about basketball!” O’Neal says. “He wanted common knowledge about the game for his act so that he didn’t look like a total fool.” Leno’s set has been lost to time, but O’Neal’s pointers must’ve worked; the NBA invited the comedian back the following year to perform at the All-Star Weekend in Houston.

Backstage before the show, Jordan mingled among the other celestial bodies, the fraternity of superstars into which he was being initiated that weekend. “We were laughing and joking and talking about the season and the game on Sunday,” he later told the media. “For the first time, I really feel accepted by everyone.”

At the All-Star Game on Sunday, announcer Tommy Edwards introduced Jordan as “the charismatic star of the Chicago Bulls!” Jordan looked almost embarrassed as the Chicago Stadium crowd gave him a thundering standing ovation.

So he said, ‘If you guys want to have some fun’—then he looked at [East coach] Mike [Fratello] and said—‘put somebody else in because I’m not losing in this building.’Doc Rivers, All-Star in ’88

From the opening tip, a playoff intensity permeated the game. “They are not playing so far like it’s an exhibition,” CBS’s Dick Stockton noted early in the broadcast. “In that era, we had a warrior mentality no matter the context in which we played,” Wilkins says. “We competed on a very, very high level. You wanted to know where you stacked up and show that you belonged. Not just through offense, but also through defense. The All-Star Game really mattered.”

It mattered so much, in fact, that Pat Riley performed his duties Sunday as West head coach after his brother Len had died on Friday at age 52 after a long illness. Abdul-Jabbar suited up following a couple of days in bed with an upper-respiratory ailment, only to set the all-time All-Star Game scoring record. Maurice Cheeks and James Worthy put in minutes despite injury. Mark Aguirre contributed 14 points for the West on just two hours’ sleep after getting married on Saturday in a suburban Chicago church (Isiah Thomas and Magic Johnson served as groomsmen) and hosting the reception at a hotel near O’Hare. Charles Barkley complained postgame, as only Barkley could, about not getting enough minutes. “I’m just wasting my damn Sundays at All-Star Games,” he told the media. “I should be at home watching them on TV. From now on, if I don’t start, I’m not coming back.”

“Competition in an All-Star Game? What an amazing concept!” Thomas says with a laugh. “In my mind, there was no such thing as an exhibition game. Magic and I, we were looked at as framers of the All-Star Game. And he and I are highly competitive. We always wanted to entertain, but we didn’t want anyone to give us anything.”

Revered showmen that they were, they knew to take into account the audience. “We always tried to make sure that the home crowd was entertained, if there was a hometown player, but not go overboard and ruin the competitiveness of the game,” Thomas says. “It was a Chicago crowd, a Bulls crowd. Jordan was at home. We wanted to make him the MVP. Luckily we didn’t have to play to him too much, because he was that good. It happened organically.”

To rewatch that game today is to see Jordan at the apex of his balletic agility. Vaulting to superhuman heights to bat away an Alex English layup. Knifing through the West’s coverage with dextrous dribbling. Pirouetting past defenders and double-clutching around outstretched arms. Swatting the ball from the clutches of Malone before dashing to the other end for a dunk.

During a second-quarter timeout, CBS’s James Brown waded into the audience to interview reigning heavyweight champion Mike Tyson. (The champ would wed actress Robin Givens immediately after the game in a small ceremony at a Chicago church.) The network’s camera then panned over Tyson’s shoulder to spot none other than Oprah Winfrey taking in the game.

At the half, even as the East was up 60-54, Jordan went into the locker room dissatisfied.

“Jordan was ticked off at halftime,” Doc Rivers, a first-time All-Star in ’88, told the Chicago Tribune’s Sam Smith in 2008. “He didn’t want to lose in his own building and he went off because guys were goofing around. So he said, ‘If you guys want to have some fun’—then he looked at [East coach] Mike [Fratello] and said—‘put somebody else in because I’m not losing in this building.’”

Jordan would go on to score 16 points in less than three minutes in the fourth quarter, leading the East to a 138-133 victory. He notched 40 points in all, on top of eight rebounds, three assists, four steals, and four blocks.

“I looked up at the scoreboard and saw he had 36 points,” Thomas said after the game. “During a timeout, I told him, ‘We’ll get you 40.’” He made good on the promise, assisting on Jordan’s last four points in the final minute, including an alley-oop dunk.

The kinship was a far cry from the ’85 All-Star Game in Indianapolis, when Thomas and Johnson were alleged to have engineered a freeze-out of Jordan, supposedly to humble a rookie they saw as cocky. Thomas denies the allegation to this day.

“Me walking into the East locker room in 1985 and telling Larry Bird and other guys, ‘Hey, this is what’s going to happen. We’re going to keep the ball away from Jordan’—it was an impossibility. I had no power,” Thomas says. “Some games you just don’t play well. Jordan did not have a good All-Star Game that year. That’s all.”

Despite repeated denials by Thomas and Johnson, Jordan came to believe that there had indeed been a conspiracy to cut him down to size. And so, hurt, he had walled himself off from other stars.

“Now, their feelings have changed. It feels genuine. I am accepted,” he told the media after the ’88 game. “Some of the things they did [on Sunday] was a conscious effort so [the beef] would be ended.”

“He already fit in, but the competition was so fierce back then,” Wilkins says. “You had to earn that respect.”

Johnson said of Jordan in ’88: “He has arrived.”

“Michael, I know you enjoyed your weekend,” Stern said when he presented Jordan with the All-Star Game MVP trophy. “In a league of stars, in a game of stars, you were the star of stars.”

Jordan lifted the award over his head as his parents looked on, beaming. “He did seem like an outsider until now,” his father, James, told the Tribune’s Sakamoto. “After today, he is accepted, very much so. They finally realized what he is going to do for other players and for the league in general. I think he was rewarded with that today.”

“That weekend in Chicago, Michael Jordan took the league to the next level and secured his place for the next decade as the dominant athlete in the sport,” Welts says. “He transformed what it meant to be an NBA player, the opportunities, commercial and otherwise, for the league’s athletes beyond the game. And there we were, on his home court, with the adoring fans cheering him on. It was the perfect stage.”

Jordan agreed. “I wish the All-Star Game was here every year,” he said.

Jake Malooley is a writer and editor based in Chicago.