On November 16, 2018, the day that he almost died in the wrestling ring, David Arquette showed up for work in a Bruiser Brody T-shirt. The fourth-generation actor turned pro wrestler was tempting fate in a way. Brody, a former sportswriter born Frank Goodish, was the most feared brawler of the 1980s and a pioneer in the violent world of hardcore wrestling. He was also killed backstage at a show.

Arquette had been lined up to wrestle in his first death match. Having accepted the booking two days earlier, Arquette had little time to prepare for it, not that it mattered anyway. Wrestlers can’t train for death matches—the most insane and bloody match in wrestling. Still, he watched a documentary on death match specialist “Sick” Nick Mondo and surfed YouTube clips of his opponent, Nick Gage.

“I had a worried feeling,” says Arquette’s wife, Christina McLarty Arquette. “I could tell David was really nervous when he left the house.” And yet he arrived at the Hi Hat, a venue in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, projecting confidence with Brody’s wild-eyed mug on his shirt as an avatar of sorts.

The match started slowly before descending into standard death match chaos. Arquette was speared through a table, had a bottle cracked over his head, and was gauged with a pizza cutter. Blood poured from his forehead. Gage, who’d served a five-year prison sentence after pleading guilty to second-degree robbery in 2011, showed no mercy. After smashing fluorescent light tubes over Arquette, he dug a shard of glass into Arquette’s forehead. That’s when the match took a dangerous turn. Arquette went for a double-leg takedown, surprising Gage, and both wrestlers tumbled to the mat. On the way down, Arquette cut himself on another shard of glass, opening a massive hole in his neck. He rolled out of the ring clutching his collar, struggling to keep the blood from gushing out.

“I was so freaked out. I thought it hit my jugular and that I was dying,” Arquette says today. “But once I knew I wasn’t dying immediately, I went back in and tried to finish it.” Arquette would escape with five stiches, but the wounds cut much deeper.

“There was a scary impact from that match,” McLarty Arquette says. “It took a toll on him mentally and physically. But he continues to love it. He continues to wrestle.”

Why is David Arquette—millionaire actor, husband, father to three children—wrestling at the age of 48? It’s the focus of the new documentary You Cannot Kill David Arquette and a question that Arquette still struggles to answer. “I don’t know,” he tells me, removing his clear Dita frames. “I don’t know why I did it for. I just felt a drive to do it. I knew I had to lose weight and was going on a weight-loss journey, so why not tie it in? I knew I was getting too old to do it again.” But a middle-aged actor doesn’t go full Randy the Ram just to get skinny (for the record: Arquette lost 50 pounds). More pointedly, Arquette’s return to the ring—and the documentary about it—feels like the actor coming to grips with himself, with his rise and fall as an actor, with the feeling of unbelonging that he’s carried with him his whole life, with the substance misuse issues that have plagued him. David Arquette wants to make a comeback, but mostly he just wants some sort of acceptance.

I’m not a punk. I’m not scared of any of these people. That’s the main thing. I’m not scared of any of those guys.David Arquette

It’s a bright L.A. afternoon in February and Arquette sits on a couch near the wrestling ring he built in his backyard. “It’s pretty ridiculous,” he admits. It’s shorter than a regulation ring and a tree branch dangles near the top rope in one corner, but Arquette loves it. Los Angeles–based wrestlers such as Jungle Boy, the 22-year-old son of Arquette’s late friend Luke Perry, often train here.

Arquette dresses like a cool dad who spray-paints trash cans to unwind, which, to be fair, he often does. He wears a Billionaire Boys Club sweatsuit, leopard-print Chuck Taylors, and some bling: a diamond stud in his left ear, a silver bracelet, wedding band, and a pinky ring adorned with his initials. He has Ric Flair tattooed on his forearm; ink of “Macho Man” Randy Savage and Miss Elizabeth reside near his right shoulder blade. The scar on his neck is buried in his salt-and-pepper stubble. A can of Red Bull sits in front of him. He’s fidgety even at home. Deep down, Arquette says, he knows his relationship with wrestling is toxic. Once, while high on ketamine during a dissociative therapy session, he realized the hypocrisy of it all: Here he is, a man who abhors violence participating in death matches. “I hate tough guys. I hate all that shit,” he says. “Now you’re simulating the thing you hate most?”

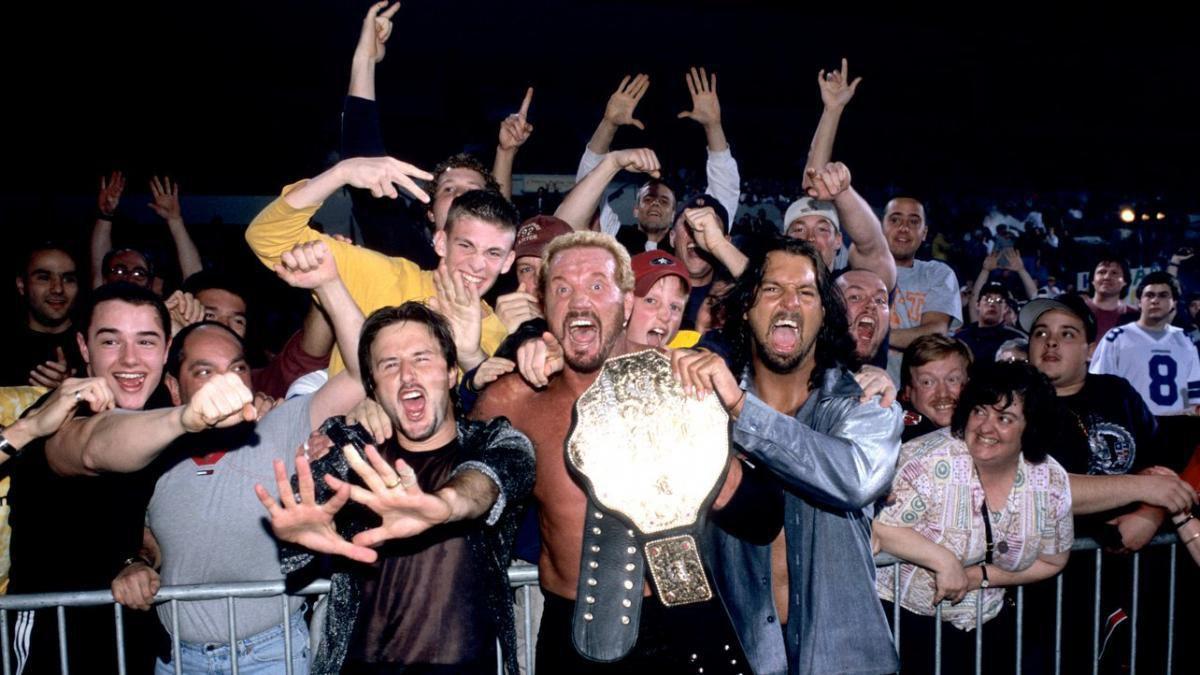

Arquette’s childhood passion for wrestling mushroomed into a fixation just as he became a household name due to his starring role in the Scream franchise, a ubiquitous 1-800-Collect ad campaign, and his marriage to Friends megastar Courteney Cox. In the spring of 2000 he got in the ring to promote the movie Ready to Rumble, and somehow ended up winning the WCW World Heavyweight Championship, then one of the most prestigious titles in wrestling with a lineage dating back to 1905. While Arquette’s title reign lasted 12 days, it torments him to this day.

Arquette portrayed a chickenshit during his first run in the business. “I’m not scared! I’m petrified!” he shrieked on the May 1, 2000, episode of WCW Monday Nitro before his first title defense against Tank Abbott. “He’s gonna kill me!” One of the announcers even referred to Arquette as a “paper tiger who hides behind his wife.” He wants fans to know he isn’t that guy from WCW.

“I’m not a pussy. I’m not a punk. I’m not scared of any of these people. That’s the main thing. I’m not scared of any of those guys,” he says, grumbling about how WCW booked him. “Growing up, we used to fight kids from Venice and all this shit, just get into street fights with Filipino gangs. So I wasn’t one to back down or get pushed around. People might think that we’re the Arquettes and this and that, but we didn’t grow up with silver spoons or anything. We grew up in a crazy part of Hollywood at a crazy time in Hollywood with a dad who was a working actor. We were middle class. If there was an actor’s strike we had to get food stamps,” he says, shifting his way out of the sun. “It’s not like we grew up snobby kids. I didn’t get a car until I was able to buy one myself. I don’t know. I just didn’t like being called a punk so much.”

The crazy part of Hollywood was Melrose and Gower near Paramount Studios. The crazy time was the 1980s. How crazy? “A Mexican gang burned our house down because our neighbor was in the gang and got out,” Arquette says. “They thought he lived in our house.” Arquette ratchets up like this once in a while, in a way that makes it hard to discern what’s true, what’s hyperbole, and what’s a mixture of both. He says he had his own gang: The Kids Gone Bad (KGB), a graffiti crew that claimed Melrose to East L.A.; his tag was Some-One, Some-1, or Some-R. Still, it was inevitable that he’d enter the family business.

The Arquettes’ showbiz roots date back to David’s great-grandparents, the renowned vaudeville duo the Funny Hebrew and the Singing Soubrette. Their son Cliff was an actor and radio performer who gained fame in the 1950s through his comic alter ego Charley Weaver. Lewis Arquette, David’s father, managed the Second City theater in Chicago before really getting into the ’60s and moving the family to a hippie commune in rural Virginia, where David was born. Lewis would grind out a workmanlike career as an actor and puppeteer with bit roles in movies and television, most notably as J.D. Pickett on The Waltons. David’s mother, Mardi, was a burlesque dancer, actor, and later, a marriage counselor. She was a bohemian with a dark side. David says she was abusive early on. Lewis Arquette, meanwhile, loved puppets and art and improvisation. “My dad was very much like a grown up kid,” he says. “I think I’m a lot like my dad in a way.”

David is very good at finding laughs. He’s kind of like Christopher Walken. He makes things interesting in places you didn’t think they would be.Jamie Kennedy, Scream costar

Arquette caught the acting bug as a sophomore at Fairfax High after landing the lead in the school play. He’s quick to mention that he was the only student to audition, knocking himself down a peg as he often does. A jolt of confidence landed after placing second in a statewide drama competition. “I was like, maybe there is something here and it’s not just nepotism,” Arquette says. “I might have some talent.” By this point his siblings Rosanna, Patricia, and Alexis had all embarked on acting careers.

After graduation, Arquette was cast in the network adaptations of The Outsiders and Parenthood. From there, he transitioned to film, with roles in Airheads, Wild Bill, and Beautiful Girls. He had a unique presence on camera; an air of unpredictability often cloaked his work. And he was equally adept at both comedy and drama. “My goal was for him to have a career like Sean Penn,” says his former manager Steven Siebert. “I saw him as being one of the critical darlings of the industry.” He appeared on the cover of the 1996 Vanity Fair Hollywood issue alongside Leonardo DiCaprio, Will Smith, Benicio del Toro, and Matthew McConaughey.

Arquette initially read for Billy Loomis, the boyfriend role in 1996’s Scream, but he felt Deputy Dewey was the better fit. “There’s not a huge stretch between me and Dewey,” Arquette says. “Though he’s a lot sweeter and more innocent than I am.” Dewey was written as a muscle head, a jock. Instead, Arquette homed in on the bumbling lawman’s insecurity and struggle for respect.

There were a lot of unknowns on Scream. Dimension, the genre subsidiary of Miramax, was a new company. The director Wes Craven, over a decade removed from the success of A Nightmare on Elm Street, needed a hit. Courteney Cox, a sitcom actor, was the cast’s biggest star. And the movie was scheduled for the crowded holiday movie season. The actors knew that the material—a teen slasher film blending meta pop-culture references with visceral gore—was smart and cool, but would anyone see it? Those concerns appeared justified when Scream opened on December 20, 1996, earning just $6.4 million during its opening weekend. But positive word-of-mouth gave the film legs at the box office and it eventually grossed $103 million domestic.

The movie’s massive success—on a fairly manageable budget of $14 million—changed Hollywood. In an instant there were imitators—I Know What You Did Last Summer, Urban Legend—while the teen movie genre also saw a boom. Meanwhile, a sequel for Scream immediately went into production, kicking off a franchise that’s still going strong today; Scream 5 is currently in development.

Dewey would become the heart and soul of the $608 million–grossing series as Arquette exuded a precise mix of wholesomeness and weirdness in all four films. He was also hilarious at times. “David is very good at finding laughs,” says Jamie Kennedy, who costarred as the film geek Randy. “He’s kind of like Christopher Walken. He makes things interesting in places you didn’t think they would be.”

Kennedy recalls the scene in Scream 2 where Dewey and Randy list suspects while sucking down milkshakes. “I’m doing my whole speech and it’s really Randy heavy and Dewey is listening and questioning.” He stops and looks and goes, something like, ‘What if it isn’t?’ It was a funny take. Then we go to the premiere and it just killed. It got the hugest laugh. I was like, ‘Wow, that was so good.’ I thought it was good when we were doing it, but it was like, ‘Wow, he really knows what he’s doing.’”

At his best, Arquette could carry indies like Dream With the Fishes and get laughs as the brother in a Drew Barrymore romantic comedy (Never Been Kissed). But his eclectic taste included kids’ shows and horror, cartoons and puppets. Arquette wanted to do it all, and his career zigged and zagged in bizarre directions, from the Holocaust drama The Grey Zone to See Spot Run to the dark comedy The Alarmist, which costar Stanley Tucci allegedly threatened to exit due to Arquette’s lack of preparation. He costarred opposite Marlon Brando (Free Money), DMX (in the underrated Donald Goines adaptation Never Die Alone), and giant animated spiders (Eight Legged Freaks); Muppets From Space was a box office disappointment.

There was no plan when it came to selecting projects. “I don’t do art like that,” he says. “I don’t live my life like that. I’m more of a spontaneous person.”

And then he stopped getting cast, aside from small indies and passion projects from first-time directors. It’s been almost a decade since Scream 4. His most recent appearance in a major studio film was in 2015, a cameo as David Arquette in Entourage. The lean years have taken a toll even though movie stardom is not appealing to Arquette at this point.

“Every huge movie star that I’ve ever met has an insane ego,” he says, “like so much so that I don’t ever want to be that famous so I have to deal with that amount of ego. It’s too selfish. It’s too much for me.”

Acting is a fickle business, even for an Arquette. And tougher more so when one suffers from depression, anxiety, and addiction issues, which make standard parts of the job like auditioning unbearable. “I get so nervous. It’s like, ‘Ugh, people are judging me,’” he says, squirming so much at the thought that he instinctively curls up on his couch. “Everything in me then says, ‘You know what? I don’t really want this as much.’”

Diamond Dallas Page will never forget the moment David Arquette learned he was about to win the WCW title. “Me and David were walking somewhere and I go, ‘OK, tonight you’re going over. You’re going to be the champ.’ He started laughing. I’m like, ‘No, dude, I’m serious.’ He’s like, ‘Yeah, right.’ I stopped, looked him right in the face, and said, ‘I’m serious.’ He’s like, ‘No, they can’t do that.’ He didn’t want to do it. He knew.” DDP pauses. “He knew nothing good would come out of it.”

Arquette’s first sojourn into the world of professional wrestling began in the fall of 1999 on the set of the film Ready to Rumble. Arquette deemed the wrestling comedy a no-brainer: It was filled with slapstick humor, his favorite; he was a big fan of Oliver Platt; had known Scott Caan since he was a teenager; loved working for Warner Bros.; loved the script. “Within the first 10 pages ‘Macho Man’ Randy Savage was in it,” he says with awe. “I was like, ‘Are you kidding me? That alone would be such a dream to meet the guy.”

David Arquette is a good human being who loved our shit. He didn’t ask to be a world champion. He never would.Diamond Dallas Page, professional wrestler

He met Macho Man and then DDP, Chris Kanyon, Shane Helms, and Goldberg, WCW wrestlers who all took on roles as actors, consultants, and stuntmen in the film. During down time, Arquette would share stories about his fandom, like when he saw Hulk Hogan fight Andre the Giant at the L.A. Sports Arena or how his dad voiced Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka in the mid-’80s cartoon Hulk Hogan’s Rock ’n’ Wrestling. Bonds were forged. Arquette put wrestlers on his Christmas card list.

When it came time to promote the film—which, needless to say, bombed at the box office, grossing $12 million worldwide—Arquette sometimes wore a replica wrestling belt. WCW booker Vince Russo noticed and sent Arquette an invitation. We’ll have you jump in and do something, was how it was put to him. A mere few weeks later Arquette was the reluctant champ.

He tried to make the best out of it. Afterward, on the advice of Ric Flair, he bought drinks for the boys, running up a $3,000 bar tab. But no amount of drinks could square the mixed feelings that came with winning. Raising the strap was a dream come true. “As a kid I remember wanting to do that,” Arquette says. “I thought it was going to be fun.” And yet, he knew it was a terrible idea; that locker-room stalwarts like Booker T were more deserving; that he had no training; that the reason he was champion was to bring WCW mainstream attention (Arquette’s win made the front page of USA Today). He hauled the belt—the famous 10 pounds of gold—to the Vancouver set of 3000 Miles to Graceland to film a promo with Courteney Cox and their costar Kurt Russell. By then, it had already become a burden.

Through it all, he was a professional in the ring. “He did exactly what a Hollywood actor is supposed to do,” says Jeff Jarrett, who knows a thing or two about actors crossing over into wrestling. His father, Jerry Jarrett, booked Andy Kaufman’s feud with Jerry “The King” Lawler. “David was a little timid, a little apprehensive, but never missed a cue.” But Arquette didn’t look like a champion. Act like a champion. Wrestle like a champion. A champion wasn’t some scared Hollywood punk. And the fans rebelled. Before an event, Arquette was posing for pictures when he was hit in the face with a glob of dirt. He looked up and saw a 10-year-old kid giving him the finger. “He was so mad at me,” Arquette remembers. “I don’t think people calculated how upset people would get and how much of a disgrace it was to the belt.”

But Arquette was a fan, and what wrestling fan would turn that down? And it’s not like he exploited it. He donated his WCW salary to the then recently paralyzed Darren Drozdov and to the families of the late Owen Hart and Brian Pillman. And here he was blamed for killing WCW, which went under 10 months after Arquette dropped the title to Jeff Jarrett.

Him? He killed it? World Championship Wrestling basically ended after Starrcade 1997. WCW died when Goldberg’s undefeated streak ended because of a cattle prod. The Fingerpoke of Doom killed WCW. Or maybe it was the Radicalz leaving for WWE. There are many reasons WCW died. That wrestling fans think David Arquette is one of those reasons still hurts him.

“David Arquette is a good human being who loved our shit,” Page says. “He didn’t ask to be a world champion. He never would. It was an angle that went awry.”

Arquette was in failing health when he decided to return to the ring in 2018. He had just been medicated for a heart attack and had two stents placed in him. Still, this was personal for him. He was motivated to prove that he wasn’t the coward he was depicted as in WCW. He’d do it right this time. Proper training. Work the independent scene. Pay his dues. Earn respect. Atone for past sins. Arquette loved the mythology of pro wrestling, a fabled world of heroes and villains—gods and monsters—and he pictured his comeback doubling as a redemptive tale.

He trained hard and maintained a disciplined diet. Peter Avalon, now known as the Librarian in All Elite Wrestling, gave him the proper wrestling training he always wanted. He did jiujitsu with Rigan Machado. Ricky Quiles taught him boxing. He downloaded the DDP Yoga app. He ate egg whites at multiple meals. No snacks. No carbs after noon. No cheating. He went to bed hungry. He shed weight and bought professional gear to flaunt his new, buff physique.

When it was time to get in the ring, he first wrestled unbilled under a mask in Tijuana, where he broke two ribs throwing a cross-body block. Injury also marred his debut singles match after RJ City connected with a knee to Arquette’s face. He showed up to work the next day with a swollen kisser. And yet, Arquette was having a blast. Joey Ryan dick-flipped him. Jerry “The King” Lawler knocked him silly with a pile driver. He felt like one of the boys. And the fans? The same fans who made his life miserable for two decades with YouTube rants, nasty tweets, and IRL provocations about how he killed WCW got behind him, he says. “I sacrificed part of my body and pain and life for them,” he says.

As for his actual wrestling—his in-ring technique—over time and with repetition he got … decent. “I’d say he’s passable as a wrestler,” says DDP, who walked Arquette to the ring last year during a show on WrestleMania weekend. Shane Helms, who teamed with Arquette during his comeback, offers further praise. “I was super impressed,” Helms says. “There were points during the match when David was in the ring and I was on the apron waiting for the tag like, ‘Wow, this guy is killing it.’”

Although Arquette still appears nervous in the ring, Helms says his greatest strength is selling for his opponents. This is where Arquette’s background both in Hollywood and WCW are advantageous. He has great facials and can tell a story with his visage. And because he’s, you know, an actor, he elicits sympathy as a babyface in peril. With his name recognition he doesn’t have to do much in the ring besides tell a story—and yet he still soars off the top rope, throws hurricanranas, and gets choke-slammed onto thumbtacks.

“Do you want to learn something?” Arquette asks, rising from the couch. “Awesome.” We wipe our feet on the ring apron—it’s a respect thing—and climb in. Up first we run the ropes, the most essential move in wrestling and an excellent dynamic warm-up. Arquette hits the cables with his back square and his tailbone on the middle rope. He holds it for a second and then explodes across the ring. Boom-THWACK-THWACK goes the familiar sound of feet pounding the canvas. “You’re taking a couple of little steps at the end,” Arquette says after its my turn. “Try to eliminate those.”

We collide with surprising force when locking up. The trick with a collar-and-elbow tie-up, he says, is to go in hard and then slacken after contact. “This goes there,” he says seizing my hand and positioning it closer to his elbow. He then transitions into an arm bar. “You need to have both feet facing me because it will make it look like it hurts more.”

He wrenches the arm. Now it’s time for me to sell.

“Nooooo,” I howl like Ric Flair in his heel prime, wincing and screaming. At this point, the Nature Boy would grab Arquette’s hair and yank him to the mat. He laughs at the idea. “Ah, but I can’t take a back bump,” he says. “I can’t do bumps like that because it fucks my neck up.”

Arquette compares pro wrestling to choreographed MMA, with the residual effect of each match resembling a car crash no matter how safe his opponent works. A pair of busted ribs wasn’t the only injury Arquette sustained upon his return. He had elbow surgery on an infected bursa and has what he calls a recurring whiplash condition with his neck. It’s also fair to wonder about Arquette’s brain. In the documentary, cameras are present when he receives a nebulous diagnosis from a neurologist. “Frankly, his results are very complex,” the doctor says. “His brain … isn’t connected in a typical way.”

Arquette is similarly ambiguous when addressing it. “Yeah, it’s kinda crazy. Yeah, I don’t know what—I don’t know what’s wrong with me. Yeah, I don’t know.” We stand in opposite corners of the ring, arms resting on the top rope. “My main thing is addiction, just kind of like I’m not sober. I’ve learned a lot more about balance. I’ve learned what I can and can’t do. Smoking pot sometimes really helps with anxiety and pain for me, once in a while. And I have a beer and something once in a while. But I’m not like the sober guy. I’ve tried. I’m not good at it. I don’t enjoy it.”

Arquette’s relapse, he says, stems from the broken ribs. Vicodin initially made the pain disappear, but Arquette is wary of opiates and so he stopped taking the meds. Then the pain returned. “Then you try to numb with other stuff,” he says, describing the vicious cycle that has claimed the lives of countless wrestlers. “Then it gets out of control. Then you have to get your life straight. I don’t know.”

When I ask Christina McLarty Arquette, who is studying for a master’s degree in clinical counseling, whether wrestling is detrimental to her husband’s sobriety, she answers, “It’s a valid question. I think it just depends on everyone’s experience.” She then suggests that Arquette’s struggles can be traced back to his chaotic childhood. “As the mental health expert in the film notes,” she says, “those injuries can set someone up for failures and relapses.” And Arquette has an abundant amount of unresolved trauma, the most recent blow being the sudden passing of his friend Luke Perry in March 2019.

Perry lived at the Arquette household when he was cast in Beverly Hills, 90210. He had met Alexis on a film called Terminal Bliss and when production wrapped he told Alexis that he was considering moving to Los Angeles, who then suggested he rent the extra room in her mother’s house. When he wasn’t watching wrestling with a teenage David, Perry went on auditions. Arquette reconnected with Perry before his death. “We had a barbecue here and he couldn’t make it, but he came over the next day with Jack and his daughter Sophie and we got to hang as a family,” Arquette remembers. “I hadn’t seen him in a while. Then I got to see him at the wrestling match. Then he helped save me.”

As seen in the film, Perry was ringside for Arquette’s death match—his son Jack, a.k.a. Jungle Boy, had wrestled earlier in the card—and he was the first person to come to his aid when his neck started bleeding. He later drove Arquette to the hospital. “Then we talked a few times and then he just passed, which was so shocking,” Arquette says quietly. “It’s another thing I’m so thankful for wrestling about is that I got to connect with my friend again.”

How much longer will Arquette wrestle? His most recent match was on New Year’s Day, and he believes he has a few more left in him. Then, he plans on transitioning into a managerial role and from there perhaps an induction one day into the WWE Hall of Fame. “It would definitely be in the celebrity wing,” he says. “There was an idea that [it] would be an amazing end to the documentary, but that didn’t happen. There are a lot more people that are deserving.” He can’t help but take one last shot at himself.

As for his acting career, Arquette continues looking for work, continues to audition no matter how painful it can be. He hopes the documentary compels Hollywood to give him another look, an aim that admittedly took a hit when South by Southwest—and the film’s debut at the festival—were canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “My initial reaction was just being so bummed for all of the filmmakers and the city, just how difficult that is on people’s livelihood,” Arquette tells me over email. “I have dreamt my whole career to be in SXSW, so for it to get cancelled, it really was unfortunate.” Instead, he and his wife (who is a producer on the film) made the most of a bad situation, throwing together a screening at their house for family and friends. For now, the film does not have streaming or theatrical distribution.

Arquette blames his demons—and not wrestling—for his professional fall. “I know in the [documentary] they allude that wrestling affected my acting career,” Arquette says. “My personal behavior probably affected my acting career more, just being a bit of a wild man and outspoken and dressing crazy and whatever.”

Arquette maneuvers around his four basset hounds in his kitchen and offers me a LaCroix and a burger. He then walks toward his living room, where the sun blisters into the atrium. Above him hangs a trio of paintings featuring Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon, and Bob Marley with the words “Kiss the Sky. Come Together. Stir It Up.”—song lyrics that double as mantras for Arquette. He then goes off in search of his most meaningful artifacts.

After a quick search, he returns with a replica WCW World Heavyweight Championship belt that Goldberg gave him. We move down the hall past the painters working on his home. He shows me a self-portrait his grandfather drew. In the next room is a bust of his father. “It looks just like him,” he marvels. “It’s weird, you get to a certain point in your life where it becomes clear what you love about life, what you really enjoy about life and what you don’t. The older you get, the less time you have for the things you don’t. I do love wrestling. I love being a fan of wrestling rather than being a participant. I love watching it. I love circus. And l love art. And I love clowns. And I love movies and music. So you just lean into stuff like that that you like. It’s about finding joy in life.”

He then reaches for one of the giant puppets his grandfather left him, a Charley Weaver doll the size of a toddler, with his trademark squashed hat, round glasses, and wide tie. “Hey, it’s Charley Weaver,” Arquette says in a dummy’s voice. He turns to me. “’Hi, how are you doing?’” He could go on like this all day, playing with his puppets. But he has to go now. Three wrestlers are at his front gate and they’re ready for their afternoon training session.

An earlier version of this piece misstated the names of two of Arquette’s coaches. Rigan Machado, not Hegan Machado, coaches jiujitsu; Ricky Quiles, not Ricky Keeves, coaches boxing.

Thomas Golianopoulos is a writer living in New York City. He has contributed to The New York Times, BuzzFeed, Grantland, and Complex.