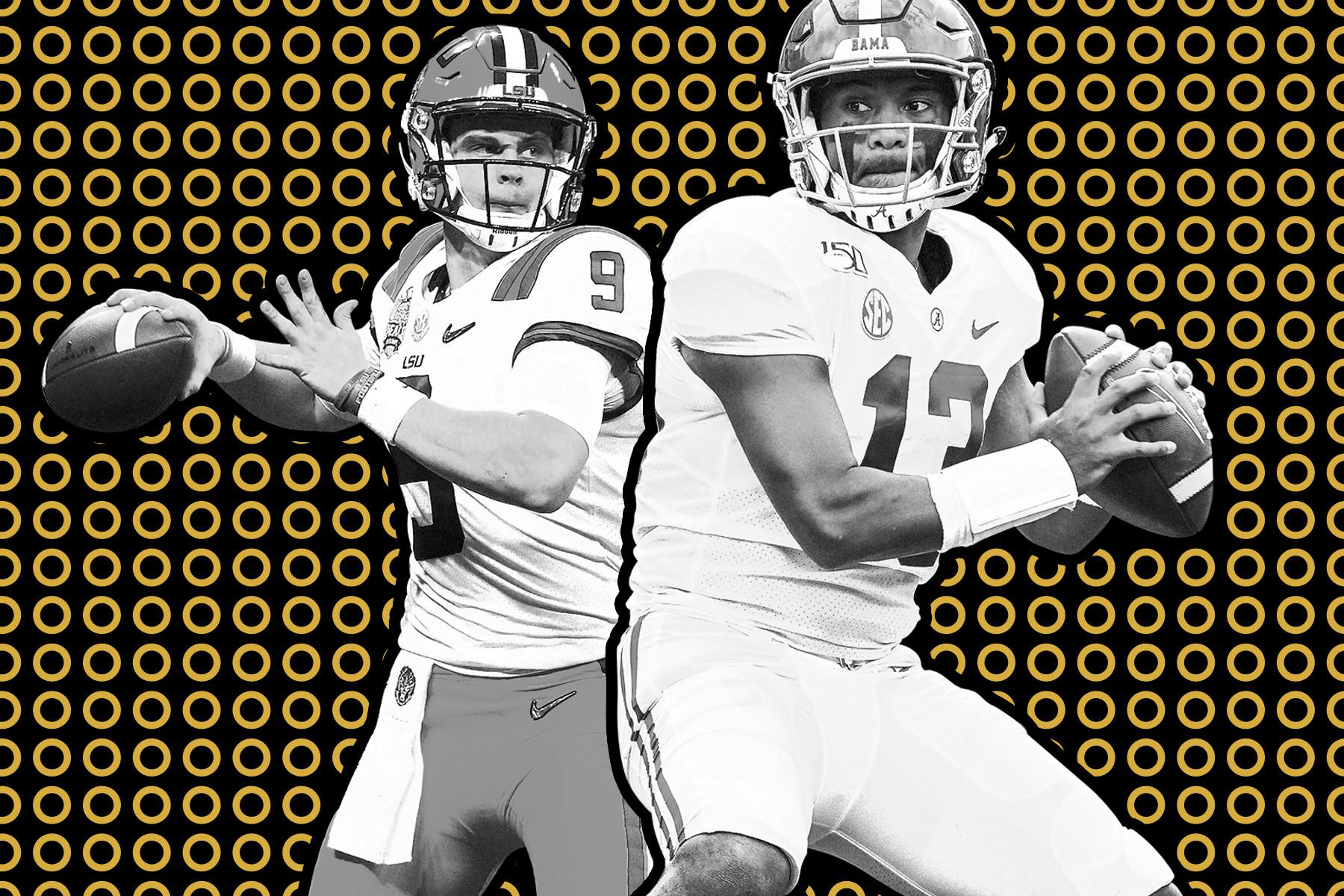

Justin Herbert looks down at every quarterback prospect he’s matched up against in the 2020 NFL draft—literally. At 6-foot-6 and 236 pounds, Herbert towers over his peers, and will immediately become one of the league’s tallest players under center. He’s also the most productive passer in this year’s class: In four years at Oregon, he threw nearly 100 touchdowns and only a handful of interceptions. He can toss the ball a country mile, and he looks damn good doing it. Herbert isn’t just the prototypical Golden Boy with a howitzer arm; his appearance matches his production. He’s widely expected to be the third quarterback taken on April 23, behind LSU’s Joe Burrow, the presumptive no. 1 pick, and Alabama’s Tua Tagovailoa. But despite being projected as a top-10 pick, Herbert remains an afterthought in any conversation about the most exciting prospects.

Burrow compiled one of the best statistical college seasons on record, winning a national championship and a Heisman Trophy this season. Tagovailoa is, when healthy, arguably the best quarterback prospect since Andrew Luck. Utah State’s Jordan Love has risen in mock drafts after a strong showing at the combine. Herbert is the other guy—much more difficult to categorize and get excited about. A four-year starter at a high-profile program in a power conference, his strengths—and flaws—have been on display for a while. His physical gifts are obvious, but he seems to offer little of the excitement or upside of the other quarterbacks in this year’s class. And yet, he still possesses enough potential to carve out a future as some team’s franchise quarterback.

“I hope, for Herbert’s sake, he gets with the right coach, and the right staff, and the right situation. Because I really believe it’s in there,” ESPN draft analyst Todd McShay said. “He’s got all the tools.”

Despite some chatter that he would be taken no. 1 in the 2019 draft, Herbert returned to Oregon for his senior season. He was born in Eugene, and raised in the shadow of the university. Professional football would always be there, but a chance to play with his brother Patrick—an incoming freshman tight end—and to finish out his career in his hometown, was too good to pass up. His grandfather, who played wide receiver for the Ducks in the early 1960s, brought him to Autzen Stadium for games when Herbert was a child—he grew up watching Ducks quarterbacks like Joey Harrington, Dennis Dixon, and Marcus Mariota. He wasn’t ready to leave Eugene sooner than he had to.

“He had a lot of unfinished business and part of that was also self-improvement, gaining ground toward the player that he wants to be,” Oregon coach Mario Cristobal said. “But a lot of it was driven by the University of Oregon, how much he loves his teammates, the program, and to leave a legacy.”

Herbert took a risk coming back. The 2019 QB class, headlined by Kyler Murray, Dwayne Haskins, and Daniel Jones, wasn’t as strong as this year’s group. There was the threat of injury, which hampered Herbert’s early college years. And beyond that, the chance that he wouldn’t be able to replicate a stellar junior season. But experts such as McShay say his decision to return didn’t negatively affect his draft stock. He improved on his junior-year numbers (3,151 yards, 29 touchdown passes, and eight interceptions), posting 3,471 yards through the air, 32 scores, and only six interceptions and completing 67 percent of his passes as a senior, leading Oregon to a Pac-12 championship and a Rose Bowl.

“This is the experience that we wanted when a lot of us decided to come back,” Herbert said before the Rose Bowl. “This is everything that I ever hoped for.”

There’s something different about the way a Herbert pass feels when it hits his receivers’ hands. It’s not just the sound the ball makes as it cuts through the air or the precision with which it finds its target. “Right when you’re out of your break, that ball is like three-quarters of the way. You better turn your head and get your hands up, because that’s coming in hot,” Oregon tight end Spencer Webb said. Herbert’s passes aren’t just placed perfectly; they come fast.

“We were in practice, and I ran a little seam route, and the safety was right behind me, and he threw the hardest, fastest pass. It was so flat, my jaw dropped,” Webb said. “I go through gloves like it’s nothing because he just rips through them.”

Oregon receivers faced a steep learning curve adjusting to the velocity of Herbert’s passes. In practice, they’d turn up the power of the Jugs machine to try to simulate his delivery. They said if they caught passes with their eyes closed, they could tell you whether the ball came from Herbert or another quarterback by the way it hit their gloves.

“I go through gloves like it’s nothing because he just rips through them.” — Oregon tight end Spencer Webb

“When I first got here, my hands would throb after practice,” Oregon running back Cyrus Habibi-Likio said. “I don’t know if it was because I was an incoming freshman, and he was kind of picking on me and throwing it extra hard. Herbert’s [passes] are just something you’ve got to get used to.”

It isn’t just a fun thought experiment to imagine the difference between Herbert’s passes and another quarterback’s. His backup and successor under center in Eugene, Tyler Shough, is no slouch. But Oregon receiver Bryan Addison can feel the difference. Shough’s throws are passes, Addison said. Herbert’s cause “awakenings.”

Johnny Johnson III, one of Herbert’s favorite targets, said he and Herbert spent the offseason working on every route in the playbook to build consistency. And while their growth certainly benefited the Ducks this season, Herbert’s natural skill as a passer has always ingratiated him with his receivers.

“It’s coming real fast, and it’s always on a spiral,” Johnson said. “You can see the ticks. You can see the white line. It’s just a blessing.”

Herbert’s physical gifts have never been in doubt. He has the prototypical size that NFL teams used to clamor for, but the evolution of NFL schemes has made it so that teams are less concerned about a quarterback who can see over his offensive linemen. The proliferation of offenses that maximize speed and space has changed the size requirements for an NFL quarterback. The past two QBs taken no. 1—Murray and Baker Mayfield—have been 6 feet or smaller. Conversely, the list of accomplished signal-callers 6-foot-6 and taller is short, headlined by Joe Flacco and Nick Foles. Herbert’s height is something scouts take into account, for both good and bad.

“I think physically, he’s as talented as you can ask for. I mean, from the size to the arm strength, mobility, and he’s really intelligent,” McShay said. “But those [height] numbers are factual. … The longer-levered guys, there’s more ways for things to go wrong. Between the footwork and the delivery aspect, there’s definitely more room for error.”

Herbert’s imposing stature belies his quiet demeanor. The way his brother Patrick puts it, “He’s always pretty quiet until he’s got something to say. Then he’ll make sure you know what he’s trying to get across.” His teammates say the self-proclaimed introvert is quieter off the field than on it. He’s quick with a joke, and lethal with his wit—often at Patrick’s expense. Across four years, and with three different head coaches, Herbert led a program from the futility of a 4-8 campaign in 2016 to a Pac-12 championship and a Rose Bowl win in 2019. He looked like a future star after posting 1,936 yards, 19 touchdowns, and four interceptions in eight appearances as a true freshman. Mark Helfrich, the coach who recruited him, was fired after that season, and when Herbert reported to spring practice in 2017, Willie Taggart was at the helm. Herbert’s performance as a freshman was a big reason Taggart took the job, and he was determined to help the sophomore quarterback find his voice.

“I had been talking with Justin about leadership and speaking up, and holding his teammates accountable to doing things right,” said Taggart, who left Oregon for Florida State and was replaced by Cristobal in 2018. “He used to get a little discouraged with himself when he’d make a mistake, and he used to let his emotions show, and I just told him, ‘Justin, you’re a big-time college quarterback. I’m sorry, but you can’t do that, buddy. Everybody’s counting on you. If you get down, we’re all down.’”

Taggart sidled up to Herbert during a scrimmage after he threw a tough pick. “Hey, Justin,” Taggart remembered saying, “this would be a great opportunity for you to talk to the guys and get the offense going.” As Taggart tells it, Herbert heeded his words.

“He brought the guys up and he told them, ‘Look, we’re going to go out here, we’re going to take this ball, and we’re going to go shove it up the defense’s ass,’” said Taggart, who now coaches South Florida. “Our offensive tackle, Tyrell Crosby, started laughing when Justin said that because I think it surprised him, too. … Justin told him to shut the fuck up, and everybody went ‘Whoa.’”

Taggart said Herbert eventually became a more effective leader. Long gone was the timid underclassman who was so shy that rather than tell star running back Royce Freeman he was lined up on the wrong side, he would run the play in reverse to accommodate him. Taggart, who was an assistant at Stanford from 2007 to 2009, compared Herbert’s work ethic and intelligence to that of Luck. And while his quiet demeanor still has some NFL front offices unconvinced, others recognize Herbert’s command of the game.

“A lot of guys walk in the room and they’re the guy, and it’s obvious. They take over the room. And that’s not Justin,” McShay said. “He doesn’t shy away from it, but then on game day his teammates love him, and they play hard for him. It’s different leadership, but there’s still leadership there.”

The Ringer’s Danny Kelly projects Herbert to be taken by the Chargers with the no. 6 pick; McShay has him as his fourth-best quarterback, behind Burrow, Tagovailoa, and Love. A big reason for that, McShay said, has to do with Herbert’s inconsistency. His play—especially his arm strength and mobility—reminds McShay of another divisive quarterback prospect, Buffalo’s Josh Allen, who was taken no. 7 in 2018.

“I think Josh Allen, for me, is probably the best comp,” McShay said. “They can outrun some people, and they’re pursuit-angle killers, because you just don’t expect them to run as fast as they do. And we’ve seen that from Josh Allen especially in the league.”

“I think Josh Allen, for me, is probably the best comp.” — Todd McShay

Herbert’s running ability wasn’t utilized often at Oregon; before the Rose Bowl against Wisconsin, he had almost as many games with negative rushing yards from sacks as he did with positive yardage. But his downfield vision, and instincts as a playmaker, along with his colossal frame, made him a tough tackle in Pasadena. Each of Oregon’s three offensive touchdowns against Wisconsin came from Herbert’s feet.

“He’s such a God-given athlete,” Webb said after the game. “I keep joking around that he’s going to be so nasty in Madden. Now he can run, too? That Madden rating is going to be good.”

Still, McShay said that like Allen, Herbert’s inconsistency and decision-making threaten to cap his ceiling.

“The first part is the physical, the second part is the scheme, and the third part, to me, is just really the mental confidence, and knowing where the ball should go,” McShay said. “There are guys that will make the same throw nine out of 10 times and put the ball right where it should go, but then they’ll come off a progression read, and their footwork will be a little bit off, and the throw will be off. … I think he has enough natural accuracy to improve if he continues to be coached well and to get his mechanics down.”

Herbert oscillates between superstardom and disaster, often in rapid succession. In Oregon’s matchup against Wisconsin in January, he was inch-perfect during his opening drive, completing four of five passes for 49 yards before stiff-arming his way in for the game’s first score. He painted corners, threaded passes, and put balls where only his receivers could find them. His only miss came when the ball shot through his intended target’s hands. This is Justin Herbert, the next great quarterback prospect.

His first pass on the ensuing drive was a bullet, as the first five had been, only this one was straight into the chest of a Wisconsin linebacker. The next was a 1-yard pickup, and the one after that a missed chance on a wheel route that ricocheted off his receiver’s hands, too high and too far behind. This is Justin Herbert, the quarterback prospect who can’t get out of his own way.

More than three hours passed between Herbert’s first drive and his last in the Rose Bowl. It wasn’t until the sun set over the San Gabriel Mountains that he came alive one final time. As the red hues above the turf mellowed into darkness, Herbert made his final stand. After recovering a Wisconsin fumble deep in Badgers territory, the Ducks, down 27-21 midway through the fourth quarter, were within striking distance of the end zone for the first time since the first half. On the drive’s opening play, Herbert faked a handoff to running back CJ Verdell, looked right, and bolted. One stiff-arm, and 30 yards later, Herbert crossed the goal line, untouched and in command.

“We were saving that one,” offensive lineman Penei Sewell said. “We were saving that for this moment.”

Minutes later, in the safety of victory formation, he dropped his head for a moment to collect himself. The sky above, now black from the January night, sparkled with green and white ticker tape. Herbert eschewed the NFL for this. And as a sea of fans swarmed the Rose Bowl field, clamoring for the briefest of interactions with their newly christened hero, it seemed worth it. A final game isn’t just an ending; it’s a transition. Soon, Herbert would find himself speaking to team executives, playing in the Senior Bowl, and going through drills at the combine in Indianapolis. But there would be time for those things later, and surrounded by those cheering him on, he thought only of celebration.

Dozens stopped him for photos in the aftermath of the trophy ceremony, some in jerseys, others in hats, but all flaunting the Ducks, and oozing pride. Security guards tried fruitlessly to usher him to the locker room, only for more Oregon faithful to appear and beg Herbert for a pose. He said yes to each and every one before making a beeline to the stands to salute those who’d stayed in celebration, high-fiving down the line like a politician working a crowd. “Four more years!” one fan bellowed out, before a few more joined in. Yards away dozens of reporters gathered, awaiting his postgame press conference. But for what felt like hours, Herbert stayed here, with the people who adored him most.

“Justin Herbert is as special as it gets as a person,” Cristobal said of his star. “He’s established his legacy. And he’s not finished yet.”