May He Have Your Attention? ‘The Marshall Mathers LP’ at 20

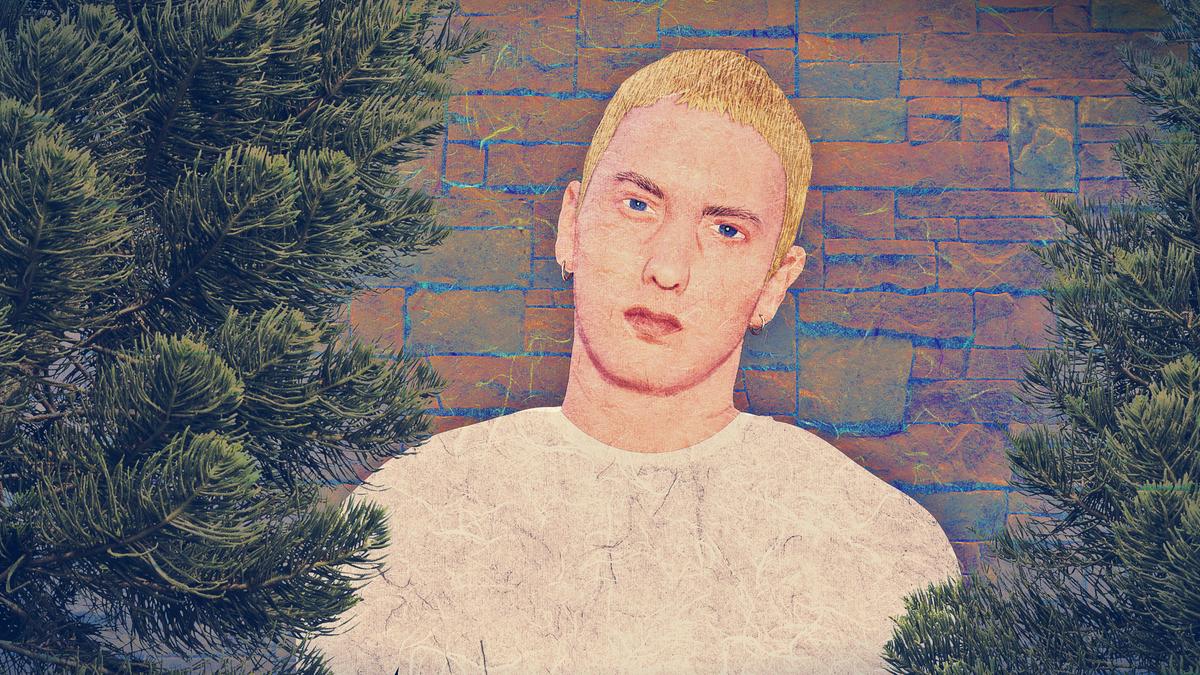

Eminem’s second major-label album was many things: a masterclass in rapping, an occasionally uncomfortable listen, a vessel for many tortured by angst, and, briefly, a national crisis. This is how he created a million others just like him.Darth Vader’s wife discovered the blue-eyed devil. His hair was bleached, his pants were baggy, and he was named after a candy-coated chocolate. Satan wasn’t a domestic terrorist, a political rival, or even an actual criminal. It was much worse: He was a rapper. And the greatest trick that he ever pulled was convincing the world to take him at his word.

To Lynne Cheney, the soon-to-be second lady of the United States, Eminem embodied the decline of Western civilization. On September 13, 2000, before a solemn chamber of musty senators, she indicted this “new, sicker” world, an ocean with “waves polluted with sex and violence.” If we didn’t stop Eminem, more mass shootings might ensue, and our imaginations shouldn’t dare to consider what else might proceed. Infinity wars based on faulty premises in foreign lands? Corporate greed and political corruption hastening a ruinous economic collapse? An ocean polluted with actual pollution?

We as Americans could not stand for this cultural despoiling. Refusing to implement the Kyoto Protocol was one thing, but think about the virginal ears of children absorbing these filthy words. Eminem was “despicable … dreadful … shameful … awful.” What’s more, Mrs. Cheney had begun to harbor the sickening suspicion that this Dr. Dre friend of his might not even be a trained medical professional at all!

“[Eminem] is a violent misogynist. He advocates raping and murdering his mother in one of his songs,” Cheney creaks in a graduate school drone to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

She distributes leaflets of the lyrics to “Kill You,” the first song on The Marshall Mathers LP, Eminem’s third studio album released 20 years ago on May 23. In 2000, it became the fastest-selling rap album of all time, a record as unlikely to be broken as Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak—1.76 million in its first week, over twice as many as the previous record-holder, Snoop Dogg. It sold 35 million copies worldwide and introduced half the globe to the sacraments of hip-hop. Eminem earned four Grammy nominations including Album of the Year, and two trophies for Best Rap Album and Best Rap Solo Performance—as well as boycotts and protests from GLAAD over its homophobic lyrics.

The Marshall Mathers LP certified Eminem as an alienated voice of a generation, a caustic wedge issue distilling the spirits of Elvis, Holden Caulfield, Johnny Rotten, Kurt Cobain, Cartman from South Park, and Tupac if he shopped at Kroger. In a postmodern abyss where everything’s performative, it might have been the last album that possessed the capacity to genuinely shock. The nexus between rap, rock, and pop radio—the ideal piñata for PTA Puritans and selectively moral censorship ghouls. Cheney was not going to miss her chance to blow; this opportunity only comes once in a lifetime. So on the Senate floor, the 5-foot-2 Matthew Arnold scholar unleashed a demonization worthy of Salem, wearing a short-clipped swoop of amber-blonde hair and a prim, boxy Dr. Evil gray suit—which she would have presumably blanched at describing as “double-breasted.”

“He glories, in the same song, that he might murder any woman he comes across. He talks about how he will choke the women he murders slowly, so that their screams will last for a long time,” Cheney dramatically lets the words linger like a slashing synth chord in a horror score. “He talks about painting the forest bright red—or maybe it’s orange, I can’t remember—with their blood. It is despicable. It is awful.”

“You put yourself through the torture of listening to this?” says a stiff, incredulous John McCain, the committee chair.

“I actually listened to it,” says Cheney.

Lynne Cheney attracts the headlines, but the World’s Greatest Deliberative Body takes turns burning the white rapper as a wicker man. Sam Brownback entails some poor schmuck to hold up jumbo poster printouts of the lyrics from both “Kill You” and Dr. Dre’s “Bitch Niggaz.” As he drowsily tells the audience that Eminem’s album had been no. 1 all summer, a woman gasps in terror. Then Brownback reads a Hittman verse about his “dick getting stuck in your windpipe.” Utah’s Orrin Hatch takes shots at Slim Shady and Nine Inch Nails too.

He opened the door to white America in a way that you had never heard.Denaun “Mr.” Porter, producer and rapper

But Cheney is the most aggrieved, urging public pressure on the board of Seagram, the parent company of Interscope. She directly links the 27-year-old rapper to the Columbine shooting that had occurred only 17 months before. She insists on a stronger parental-advisory rating system. Dripping with contempt, she decries the madness of the previous week:

“I don’t follow the entertainment industry closely in all its aspects, but every once in a while, something like Eminem pops up,” she sneers, gathering strength from the shared outrage and disdain of the world’s most powerful men and women, before citing a made-up award. “Eminem received three awards from the entertainment industry last week, including Best Male Performer at the MTV Awards. Can you imagine that the entire industry honors this man?”

It really was a job for him. Twenty years is long enough for memories to disintegrate, to allow historical revisionism or Skylar Grey hooks to alter our impressions of what really went down, for the Sonny Bono and Y2K punch lines to age poorly. There are shifting cultural mores that blind us to the regrettable indiscretions of our youth. But in that 45-month window between the February 1999 release of The Slim Shady LP and the film and soundtrack to 8 Mile, Eminem was the epicenter of pop culture.

If one of Tom DeLonge’s aliens visited Earth and asked what millennial American life was like, you’d take him to the 2000 MTV Video Music Awards. He could even sit next to the Blink-182 co-lead singer and his bandmates, who played “All the Small Things,” the song that won them a Moonman for Best Group Video.

Consider the staggering list of nominees at Radio City Music Hall on that sticky September evening—only one week before Lynne Cheney performed a librarian’s rendition of “Hit ’Em Up” on the Senate floor: D’Angelo, Aaliyah, Destiny’s Child, Jay-Z, Juvenile, Q-Tip, Lauryn Hill, Rage Against the Machine, Bjork, Blur, The Chemical Brothers, Nine Inch Nails, Madonna, Red Hot Chili Peppers, ’NSYNC, Ricky Martin, Metallica, Sisqó, Stone Temple Pilots, and uh, Papa Roach.

Despite not being honored, Janet Jackson and Nelly performed. DMX was scheduled to bark about not being a nice person, but pulled a last-second no-show for the second straight year.

It’s unlikely that we’ll ever see such a moment again. In its prime, before the permanent atomization of the internet, at the zenith of the music industry’s star-making money machine, MTV gathered the visionaries of neo-soul and ’90s R&B, ’80s pop, Southern rap, grunge, the best (and worst) of rap-rock, mall-punk, the boy band and girl groups, the titans of Britpop, alternative rock, avant-garde indie, jazz-rap, the Latin explosion, UK techno-rave, industrial, the jiggy era, and Sisqó, the Vasco da Gama of thongs.

At the pinnacle of pop’s Olympus reigned Eminem and Britney Spears, a platonic Zeus and Hera, uncomfortably intertwined, deceptively similar, and embroiled in a one-sided war—with Carson Daly playing the role of Eirene, Greek goddess of peace. The parallels transcended the fact that Eminem eclipsed Spears’s record for first-week sales by a solo artist, just one week after she set it with Oops! ... I Did It Again. Both came from indigent families dogged by substance abuse and mental health issues, struggles that later caught up to both artists. Both dyed their hair blonde, quit high school to pursue music, relied on proven super-producers for their biggest hits, and hailed from bleak towns ravaged by the loss of manufacturing (Kentwood, Louisiana, was once the dairy capital of the South; Detroit is the Motor City). In his mid-20s, Eminem nearly overdosed on codeine tablets after discovering that Britney’s label, Jive, had no interest in signing him. The yin-yang nature of the pair fits well: Yin literally translates to shade—although don’t tell Marshall that the Confucians saw that as the female trait.

The 2000 VMAs began with Britney ripping off a fedora and pinstripe suit to reveal a flesh-colored bra and sheer pants smothered in Swarovski crystals. For about four seconds, the world collectively wondered whether she was nude, lost and regained sentience, and watched her striptease a rendition of “Oops! … I Did It Again” that shattered the lingering shards of an age of innocence. If Britney Spears was the American Dream incarnate, Slim Shady personified its nightmare. Eminem’s alter ego was the laughable prankster, spinning homicidal bloodlust that was so absurd that few teenagers could believe that any adult actually took it seriously. He was a troll before the idea became fully ingrained. The catch was that Marshall Mathers lurked in between, charting the existence of those left behind by a crooked winner-take-all system. Those for whom innocence was a laughable delusion, who would never win Prom King or even go to prom. Date Britney Spears? They’d probably never even be able to afford a ticket to the concert.

Marshall Mathers, a vessel for those tortured by angst, apoplectic at unseen internal enemies and dimly glimpsed external forces. The son of a teen mom, he proudly failed the ninth grade three times. He was a savant manifestation of the superfluous men whom Hannah Arendt warned about, lonely and condemned to a postindustrial dead-end future of menial labor. Right up until fame hit, Eminem was living in a trailer and flipping burgers and washing dishes at a restaurant called Gilbert’s Lodge (his factory job in 8 Mile seems glamorous by contrast). He was the most articulate emissary of an inarticulate class, a symptom of a condition that the Lynne Cheneys wanted to wish away by congressional fiat. His response was another sacred American tradition enshrined in the Bill of Rights: a flip of the middle finger and a “fuck you.”

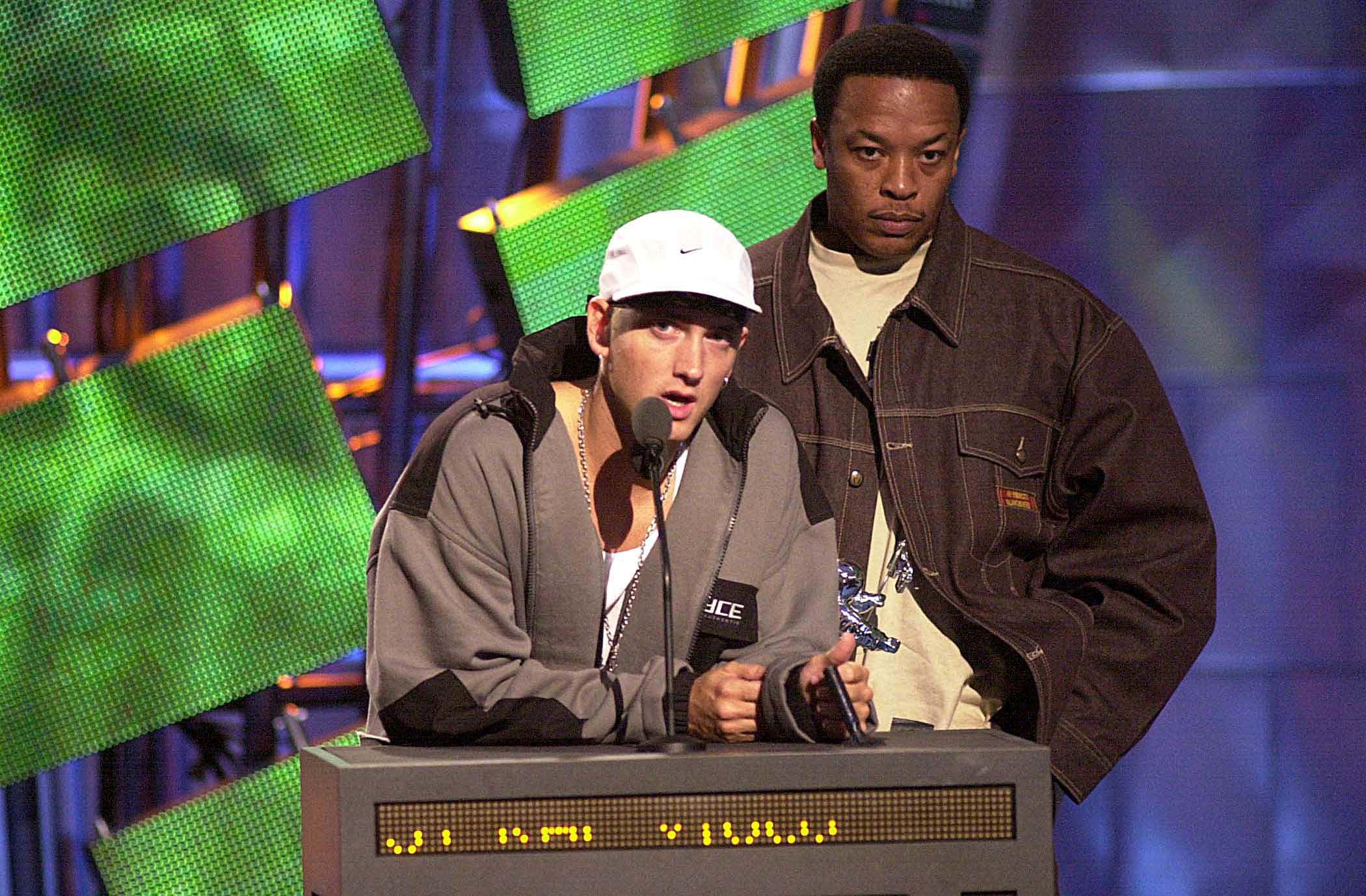

“He opened the door to white America in a way that you had never heard. There was no one out there talking shit … in the way that he was about his mom, Kim, the bad side of what was going in the country,” says producer and D12 rapper Denaun “Mr.” Porter, a longtime collaborator who was instrumental in forging the Slim Shady sound on Eminem’s early independently released projects. “He knew who he was talking to, and never tried to step on anyone’s toes. … It was the voice that white America didn’t have, and it bridged the gap because black people were like, ‘He’s telling them all the news. We like him. He’s not holding anything back.’ When you added the Dre cosign, it was a wrap.”

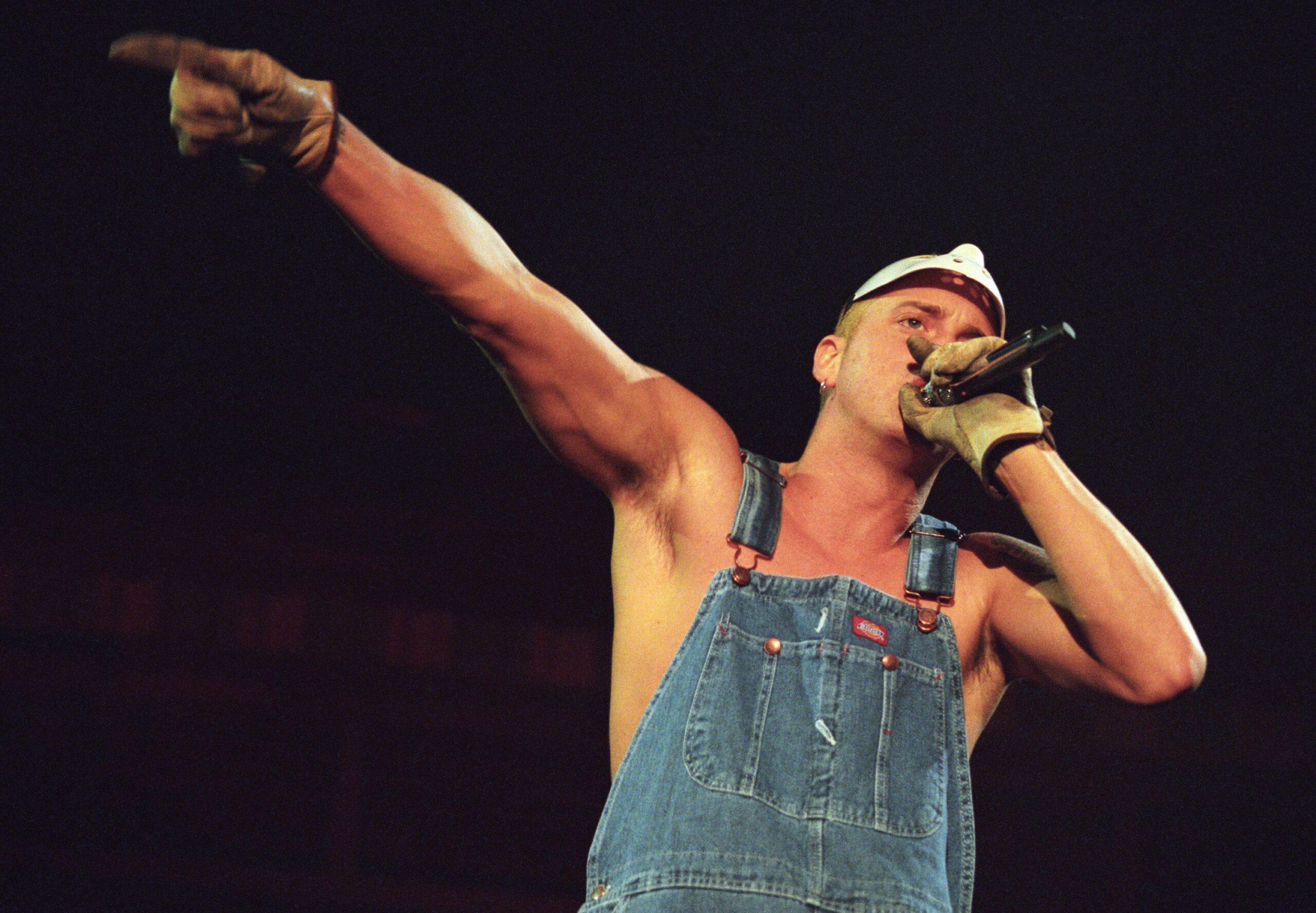

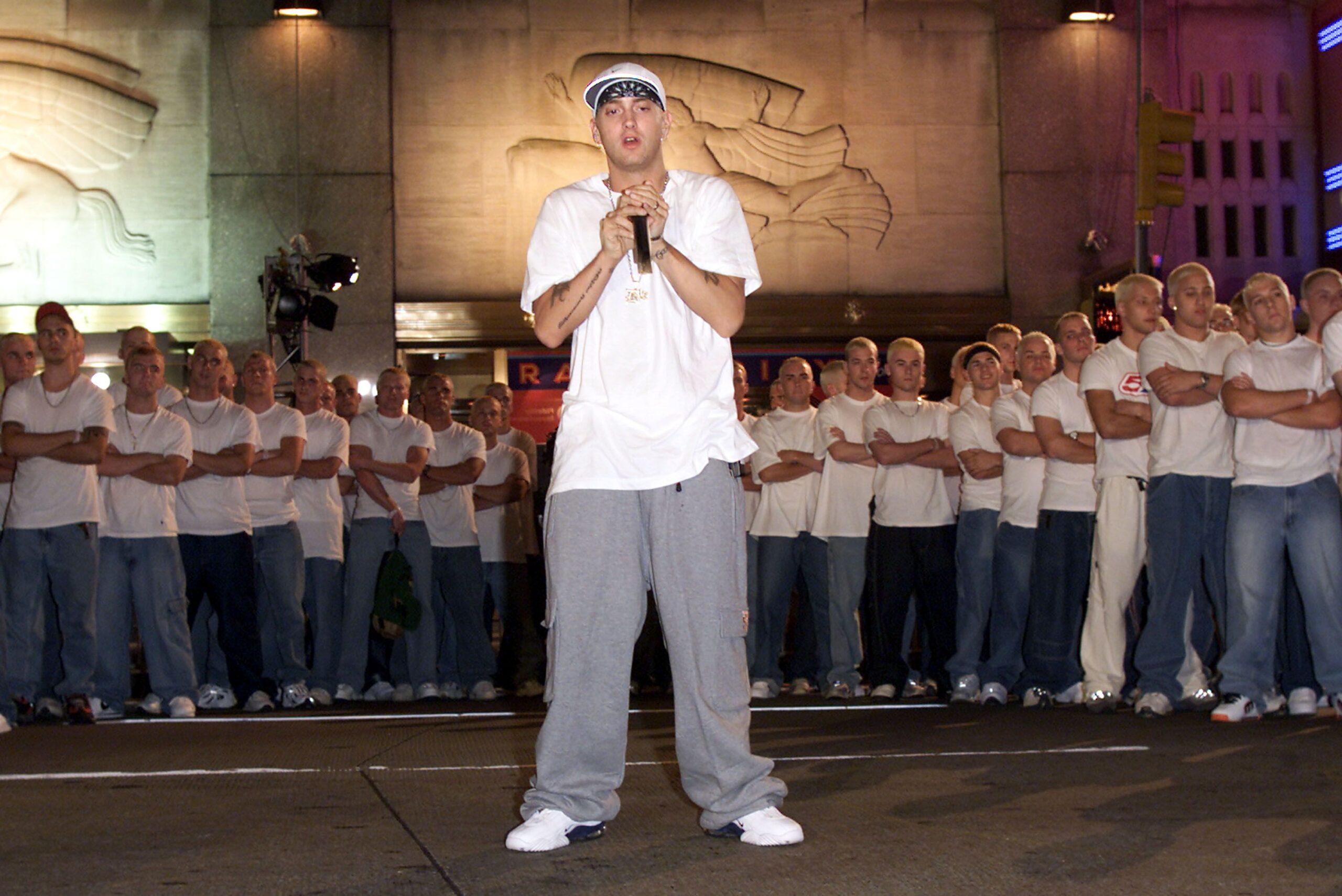

Now, the chickens were roosting at Radio City. Well, actually, they formed a barricade outside on Sixth Avenue, arms crossed over their plain white tees. Nearby and off-screen, GLAAD staged a protest over MTV’s promotion of such a “hateful, homophobic, and misogynist artist.” As a token of contrition after Eminem’s performance, the channel airs a 30-second spot PSA that “educates the public and discourages violence against the gay community.” But no one watching knows what’s about to come next. The Wayans Brothers introduce Jim Carrey, the “the star of Me, Myself & Irene … the man of a thousand faces,” who struts out and drops it low to the sounds of Foghat, as the crowd chants “Carrey!” In another lifetime, one of the only Caucasians on In Living Color had crushed the careers of two previous great white hopes, Vanilla Ice and Snow, like a cross between Weird Al and 50 Cent. Nearly a decade later, Carrey was Hollywood’s most bankable comic and forced into flogging the Grinch movie with a promotional appearance.

“I enjoy Eminem’s music but he scares me,” Carrey mugs in a church-lady voice.

With a smirk, he tells the crowd, “His lyrics are totally socially unacceptable.” Cheers. “But I think if we just spend some time with our kids, we’ll be OK.” With that, Carrey introduces Eminem to glass-shattering applause, and the camera pans outside of the fabled venue where Holden Caulfield once found a Christmas pageant to be so phony that “old Jesus probably would’ve puked if he could see it.”

May I have your attention please. One hundred Slim Shadys scowling on a warm night in Midtown Manhattan. All lined up, faces sickly pale in the pools of sulfur light, scalps bleached blonde, blue jeans big enough to fit a family of four. Maximus the Destroyer, fast rapping in a wife-beater about Tommy Lee abusing Pamela Anderson, cannibalism, and Shady’s own tough but fair decision to murder Dr. Dre. Did Dick Cheney’s heart briefly stop that night? Did Lynne understand the Tom Green humping a dead moose reference? And what did the Bush twins think?

“The 2000 VMAs were a real milestone … it helped people realize that I was here for real,” Eminem would later confess in his book, The Way I Am. “I was trying to be as cool as I could and keep my composure, but for at least the first 30 seconds of the song, I could not shake the nerves off.”

Understandable. The previous year at the VMAs, Eminem performed “My Name Is” and a Dre-aided “Guilty Conscience” from The Slim Shady LP—the album that established him as an MTV darling and the first credible mainstream white solo rapper. He was already triple-platinum, a huge star, but somehow came off a little lost. A rapper wary of acceding to the degrading tenets of pop stardom, drowning in a backward Tigers hat and an oversized hoodie that blinked “Role Model.” It all changed by the time he dropped Marshall Mathers, a record that unleashed something seething and atavistic in the national character—an ugly reflection in a cracked mirror that spoke in crude code to anyone under 21. A legitimate phenomenon. The genius of that 2000s VMA performance extended beyond concept and execution; it tapped into a deeper psychic matrix.

That spring, around the same time that “The Real Slim Shady” hit MTV and radio, my college baseball team (almost) unanimously decided to shave and bleach their heads for a team trip. I was the lone holdout, sensing that it would give me heavy Big Bird vibes; one of my few fashion choices from my freshman year that I can look back on with pride. The decision was slightly ironic because I was probably the biggest rap fan on the team. But that was sort of the point; Eminem’s appeal traveled far beyond people who read The Source every month. His third album remains the best-selling rap album of all time. Part of it was race, part of it was eternal teenage tastelessness—the crass and puerile jokes, the reflexive adolescent desire to spit in onion rings while working at Burger King. It was also just a moment in time. Kids want to be cool, and at that point, Eminem was the coolest motherfucker alive, at least in a way that seemed remotely accessible. No one was about to big pimp on yachts with Jay-Z, Bun B, and Pimp C or smear themselves with blood like DMX.

There have been plenty of rebels since Eminem, but that was the last time the sides seemed so starkly delineated, at least on such a high-stakes level. It was the natural evolution of that scene from The Wild One where a sardonic biker girl asks Marlon Brando what he’s rebelling against and he deadpans, “What do you got?” But the answer was now clear: the corrosive hypocrisy of the adult world, the sucrose emptiness of pop culture, the pervasive fakeness and artificiality of polite society, the snakebit corporate greed that poisoned everything into a commodity, and I guess Will Smith not cursing? Here was Eminem, the wild gunman from abandoned and left-for-dead Detroit, spitting The Real: “The things you joke about with your friends inside your living room. The only difference is I got the balls to say it in front of y’all. And I don’t gotta be false or sugarcoat it at all.”

We’d send over a song, he’d immediately have the lyrics written for it. They were all good too. That was when I really realized the extent of his genius.Jeff Bass, F.B.T. production team

With two decades of hindsight, it feels strange and slightly embarrassing to consider how much it all meant. As always, the lines were blurred. The Real being always open to interpretation. The truth, an arbitrary matter of who was telling the story. Maybe someone should have just told me to watch Rashomon? “The Real Slim Shady” wouldn’t have even existed if not for Interscope CEO Jimmy Iovine—who would later become a billionaire selling branded headphones—who insisted that the album wasn’t finished and Eminem still needed “the single.”

They even shaved a few years off his age on those early promo runs, just so kids would find him younger and more relatable. Eminem was unquestionably an outsider, but even by then, rebellion was a deeply commercialized pose. (And no matter how much he insisted, no slander could convince me that Britney didn’t have bangers.)

The honesty struck a nerve, but the “authenticity” might as well have been manufactured alongside that bottle of peroxide. After Eminem signed to Aftermath, Dre insisted that he needed a new look. Maybe this all would’ve happened without the twin marketing genius of Iovine and the good doctor, who learned from the greatest controversy magnet of all time, Eazy-E. Upon seeing Eminem for the first time with bleached hair—the result of two hits of Ecstasy and a serendipitous trip to a drugstore with Royce Da 5’9”—Dre went dead silent. Flashing the Keanu “whoa” face at his protégé, he exclaimed, “That’s it, we found your image.”

Even if there were only 100 Slim Shadys at Radio City, millions more watched transfixed at home, including a few who somehow managed to refuse the pull of platinum hair. Should you have found him vile and loathsome, you still had to admit that he rapped circles around almost anyone who had ever lived. A fire hose of hilarious invective and reproachable venom, dazzling pyrotechnic bursts of precise syllables and coiled intensity. It felt like a manifesto for a new generation, one who potentially had the capacity to fight against the rising tide of slick corporatization and frosted-tip fraudulence. Maybe it was all naivete and willful ignorance, but there wasn’t anyone who remained seated. Even Puff was dancing.

It was supposed to be called Amsterdam. The original title of The Marshall Mathers LP seemed appropriate at the time. The Dutch capital doubled as the international axis mundi of Ecstasy, ’shrooms, and weed. With the rave era in full flight, the Amstel River might as well have been laced with MDMA. When Eminem and his crew posted up there on a promotional jaunt for 1999’s Slim Shady LP, he described the scene as “everyone doing drugs—all the time, everywhere.” That was a crucial part of early Eminem’s appeal. Rappers generally moved weight. Eminem epitomized the artist as an avid drug consumer. “I’m Shady” doesn’t even bother to leave room for doubt, whimsically ticking off the drugs that he does and doesn’t endorse. For teenagers dismissing the hyperbole and lies of D.A.R.E. America, Slim Shady was the new Dr. Gonzo.

In contrast to the gilded repression of the states, Amsterdam exuded a sense of liberation, a promise of what could happen if everyone wasn’t so neurotic about everything. The trip also might have been the last time Eminem would remotely resemble a normal civilian. By November 1999, Dre’s 2001 enshrined Eminem as the biggest rap star in the world. The gangsta rap pioneer went eight times platinum with two Eminem songs (“Forgot About Dre,” “What’s the Difference”) that never exited terrestrial radio rotation. The former earned Em the “Hip-Hop Quotable” in The Source, a lifelong dream and the ultimate hard-to-earn cosign. The following month, Bad Boy dropped Born Again, the posthumous chart-topping Notorious B.I.G. tribute that no one remembers for anything but the elysian Eminem and Biggie shootout “Dead Wrong”—one of the few times anyone ever approached the rarified stratum of the slain legend.

You can’t discount the impact of the early file-sharing sites, their names long buried in the hippocampus alongside hexed recollections of inadvertently memorized Bloodhound Gang lyrics: Kazaa, Audiogalaxy, Lycos, LimeWire, Scour, Morpheus, and the vanquished king, Napster. As those song-trading networks flourished, Eminem’s entire underground catalog suddenly became readily downloadable. He might have been signed to Dre, but he also OD’d on dust on Soundbombing II alongside subterranean funcrushers Company Flow, Mos Def, and Talib Kweli, Common and Pharoahe Monch. He popped pills with tube socks filled on a Missy record and bulldozed freestyles for legendary rap radio DJs like Sway & Tech, Tony Touch, and Stretch Armstrong. In a two-month stretch, he committed arson on 2001 and screamed “fuck the police” on Funkmaster Flex’s compilation dedicated to grimy NYC tabernacle The Tunnel. If any Ché-bereted purists decried the Dre partnership as a sellout move, Eminem repped Newark’s Outsidaz, one of the most underrated and rugged crews in rap history. The only rapper on the Warped Tour and Lyricist Lounge—in both the Case Logics of Backstreet Boys–bumping sorority girls and backpackers burning shiny-suited effigies.

Recorded in two months of marathon, drug-fueled studio sessions across the San Fernando Valley, the Marshall Mathers LP found Eminem under pressure from all angles: His mom had filed a $10 million defamation lawsuit, long-lost relatives (including his absentee father) emerged with their palms out, the Parents Music Resource Center and GLAAD demanded his crucifixion, Interscope needed a pop hit, and the fear of not repeating the success of his breakout loomed. Tragedy occurred when Bugz—an original member of Eminem’s crew D12—was murdered in Detroit. Kim and his daughter, Hailie, briefly visited L.A., but fights between him and his wife were constant and vicious. He filed for divorce three months after the album dropped; five days after that, Kim sued him for $10 million.

“The whole message behind The Marshall Mathers LP is just to show people that I’m just like them,” Eminem summarized his mission to MTV. “I never knew that I was going to get this big … that any of this was going to happen to me. The first album was a lot of punch lines. But this album is on a little more serious vibe to it. It’s me telling it like it is to the third power.”

The MMLP sessions split into two camps: Dre’s team and Detroit’s Bass Brothers, who had worked with Eminem since his beginning. Each produced roughly half the record. Dre’s squad orbited between Larrabee Sound Studios in North Hollywood, Burbank’s Encore, and even the fabled Death Row studios—Tarzana’s Can-Am, where Marshall Mathers could absorb the Henny-soaked spirit of Makaveli. Dre and his coproducer Mel-Man programmed the drums, alongside guitarists Sean Cruse and John Bingham, keyboardist Tommy Coster Jr., and secret weapon Mike Elizondo—the bass god rumbling behind much of Dre’s darkwave funk from the Firm’s “Phone Tap” through 50 Cent’s “In Da Club.”

Sessions usually began with rubbery instrumental jams while waiting for Eminem to appear with his crumpled notebooks of chicken-scratch lyrics. Occasionally, he’d describe the sounds heard in his head, and the musicians scored it like a movie plot. Energy bursts came from visits via the eternally hyped Xzibit. For the “Bitch Please II” session, Nate Dogg sat enigmatic and quiet in the corner: smoking, sipping, marinating. Dre, Snoop, Eminem, and X to the Z laid down their verses. After five or six hours without saying a word, the late Long Beach hook messiah finally stood up and sumptuously crooned: “And you don’t really wanna fuck with me / Only nigga that I trust is me / Fuck around and make me bust this heat.”

The last song recorded was “The Real Slim Shady.” Both Eminem and Dre insisted the album was finished, but Iovine sagely cautioned that neither “I’m Back,” “Who Knew,” nor “Criminal” worked as first singles. For a month, Eminem holed up in lavish L.A. hotels hacking at commerce-as-art, flailing to set the “Real Slim Shady” hook to a beat. Time was running out, and Dre was getting ready to leave the studio late one Friday night. A desperate Eminem forced Elizondo and Coster to keep jamming. Finally, Coster played the Baroque toy-piano riff that starts off the biggest rap song to ever feature a flex about sitting next to Carson Daly and Fred Durst at the VMAs. Inspired, Eminem requested a few melodic tweaks and called Dre back into the room to complete the song in the early morning. They had a label meeting the next afternoon in which Interscope shot down “The Way I Am” as a first salvo (“a great song, but not the first single”). Back against the wall, Eminem asked them to wait until Monday to finish “The Real Slim Shady,” and you already know the rest.

“Dre is the closest thing to Quincy Jones. He hears things in both a very big-picture way and with microscopic focus, and he can switch back and forth instantly,” Elizondo says of Compton’s own Obi-Wan. “He EQ’d every kick and snare, every bass and guitar. The vocals had to fit just right. He inspired the musicians and made them feel good, but also pushed them to greatness without being an abusive tyrant. Nothing got out until it passed his test.”

Detroit congregated at Burbank’s Mix Room. There, the Bass Brothers, Eminem, and DJ Head created “Marshall Mathers,” “Drug Ballad,” “Criminal,” “Amityville,” and “The Kids,” the bizarrely endearing South Park fan-fic that replaced “Kim” on the clean version. That’s the sort of album this was: The sanitized edition features a parodic “just say no” nursery rhyme about the hazards of feeding Ecstasy to squirrels, and a man driven to brutal murder by marijuana. By this point, the Bass Brothers had worked with Eminem long enough to custom-tailor the tracks to match his mercurial temperament. Sometimes he was angry, sometimes he was playful, and sometimes he was so high that he needed to invent Adult Swim rap.

“He was like a machine,” says Jeff Bass, one-half of the F.B.T. production team, alongside his brother Mark. “We were simultaneously working on production for The Marshall Mathers LP and the first D12 album, and as soon as we’d send over a song, he’d immediately have the lyrics written for it. They were all good too. That was when I really realized the extent of his genius.”

The lone outlier was “Stan,” which fortuitously arrived when the venerable New York producer Mark the 45 King heard Dido’s “Thank You” in the Gwyneth Paltrow romantic comedy Sliding Doors; Eminem reportedly thought the sample was from the ’70s. It’s become a song so seared into the cultural lexicon that it seems created solely for the purpose of commemoration in VHS countdowns. The final stanza feels superfluous, reducing the subtleties by explaining what had just happened, in the offhand case you didn’t catch it. But removed from the burdens of over-repetition, it remains a haunting, if slightly treacly, epistolary narrative—the closest hip-hop has come to Taxi Driver. Eminem’s performance alongside Elton John at the 2001 Grammys contributed as much to the mainstreaming of hip-hop as nearly anything, before or since. The moment when your grandmother asked you if you liked this “Eminem fellow.”

Social critics often branded him a wholly original mutation, but he was a manic scholar of rap tradition. His lower-class white-male status offered a novel lens, but the nuclear syllable fission came from endless study of Big Daddy Kane, Kool G Rap, Nas, and AZ (a stylistic intricacy that Em bequeathed to Kendrick Lamar). He’d memorized Masta Ace’s SlaughtaHouse and battled for his life at Detroit’s Hip Hop Shop, which you’ve surely seen dramatized via the oeuvre of Mekhi Phifer. (RIP, Proof, whose influence was paramount.) The cartoonish voices and chimerical storytelling riffed on Biggie and Slick Rick. The goofy drug humor borrowed from Redman. The psychedelic Detroit horror-core archangel Esham was so significant that Eminem even shouted him out on The Slim Shady LP’s “Just Don’t Give a Fuck.”

Beyond the four-dimensional virtuosity and berserk imagination, Eminem intuitively translated Tupac’s “fuck the world” mentality to disaffected white suburban teenagers without sacrificing hip-hop credibility. This too was strength and weakness. Throughout the ’90s, homophobia, hyperviolence, and misogyny were rife in hip-hop, but “save the children” types rarely cared until it outgrew the partially segregated confines of the genre (provided you didn’t advocate killing cops). No Lynne Cheneys petitioned Congress about the perils of “Pregnant Pussy”—though to be fair, Bill Clinton had his “Sister Souljah moment” and Tupac declared war on anti-rap crusader C. Dolores Tucker.

But once parents’ groups and social justice organizations piled on, Eminem quintupled down on the off-color humor. Like Pac, Eminem compulsively needed to stoke controversy, piss people off, and force enemies and fans into their respective corners. They knew the ledge, and actively laughed at what they considered arbitrary limitations. That doesn’t excuse the lousy excess, but Eminem nakedly strived to fulfill the fifth element of hip-hop: Your parents are supposed to hate it.

“Half of the satisfaction that I get from releasing music comes from the look on people’s faces when they hear it,” Eminem said in 2000—in exactly the place you’d expect to hear someone say something like that: an internet chat room hosted by AOL.

Quotes like that were half-cop-out and half-reason-for-being. When the jokes worked, it felt transgressive and shocking. When they didn’t, it felt indefensible. The domestic-violence-turned-murder-fantasia about Kim is a gruesome song to listen to, now and then. It’s been two decades and no one has ever given a plausible explanation for the frat-boy homophobia leveled at the Insane Clown Posse on “Ken Kaniff.” The Versace gags on “Criminal” always seemed stale and artless. Whether it employed his Slim Shady guise or not, the real Marshall Mathers gave his detractors legitimate ammunition by writing reprehensible bars like “hate fags, the answer’s yes.” And as dark irony and presidential-level trolling have become the norm, none of this feels as subversive or slippery as it once did.

You can be appalled forever, but shocked only once. While it might rank among the most scabrous rap albums ever, the lasting genius of The Marshall Mathers LP doesn’t come from its Halloween gimmicks to frighten bored Rotarians. It comes from its deranged alchemy of steroidal rap athleticism; haywire musicality; odd goofball charm; and lingering, astute cultural criticism. The Dadaist under-the-breath ab-libs and sarcastic counterpoints. It’s when he morphs into a human scratch on the “I’m Back” hook, strangling himself, threatening Charles Manson, and becoming an existential ventriloquist act who anticipates and answers his own questions.

“Who Knew” surgically eviscerates a blame-happy culture that refuses personal accountability for parental failings and blames mass shootings on art rather than a lack of gun control. He warps his voice so that “I’m sorry, there must be a mix-up” sounds like it’s being delivered over a Kmart intercom; in the next breath, he scoffs, “You want me to fix up lyrics while the president gets his dick sucked?” Eminem had the self-awareness to understand his core appeal by starting the song, “I don’t do black music / I don’t do white music / I make fight music for high school kids.” In one aside, he’ll torch the contradictions underpinning a corrupt society; in the next, he’d kick a Cab Calloway scat about Christopher Reeve.

Nor was any of this accidental. In an interview given around the release of The Marshall Mathers LP, Eminem describes his music as “sarcastic and political.” “Kill You” might have seemed grotesque out of Lynne Cheney’s mouth, but the congressional poltergeists elided the fact that it was all self-mockery. He shrieks, a ludicrous human cartoon, about raping his own mother, then shapeshifts into a frazzled magazine editor aghast that they gave him the Rolling Stone cover. Just when it feels a little too narcissistic, there’s “Bitch Please II,” an all-time, windows-down West Coast banger. I once watched Tyler, the Creator—Eminem’s most direct artistic progeny—interrupt our interview when the Death Row–meets–Aftermath posse cut came on in the Odd Future store. Instantly, he became 9 years old again, beaming, rapping every single bar of Eminem’s verse.

If one song encapsulates the frustrations and brilliance of Eminem, it’s “The Way I Am.” It’s the title of his autobiography, his first sole production credit, and the vulnerable-but-enraged confessional that convinced millions to accept him as Serious Artist. It’s also the one where his vocal eccentricities started to ossify into easily parodied tics—where Slim Shady, the winking class clown in Groucho Marx glasses became grim and self-serious. You can almost see the scalding cauldron spilling over into this, where he exchanges the playful lunacy of his early work for hypermathematical perfectionism. Eminem would later admit that he’s forever chasing The Marshall Mathers LP, “the height of what I could do.”

His performance at the 2000 VMAs is instinctively recalled for “The Real Slim Shady”—specifically, that entrance that felt both lawless and ordained. But after the beat stops, a gunshot effect rings out, and the bleached imitators exit from view. It’s just Eminem, his microphone, and Proof as his hype man and umbilical connection to his past. Observed in a vacuum, it feels slightly overwrought—the most popular rapper of all time, historically messy and prodigiously talented. Growling and grabbing his crotch, he performs “The Way I Am,” rapping about the intensity of the pressure and how radio won’t even play his jam when they’d play nothing but.

There is also the feeling that all the points have converged. Here is Marshall Mathers complaining about the sensation of being eaten alive, our exploitive lust to consume every part of him for the sake of entertainment, our all-consuming need to boost the signal of those blurting the loudest. You can glimpse the cycles of blame spiraling in all the wrong directions, our refusal to accept tragedy unless it feels personal, the headlines that will eventually stop being believed. He is asking the same questions that never seem to get any honest answers. And it becomes hard to ever remember a time before.

Jeff Weiss is the founder and editor of POW. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, and GQ.