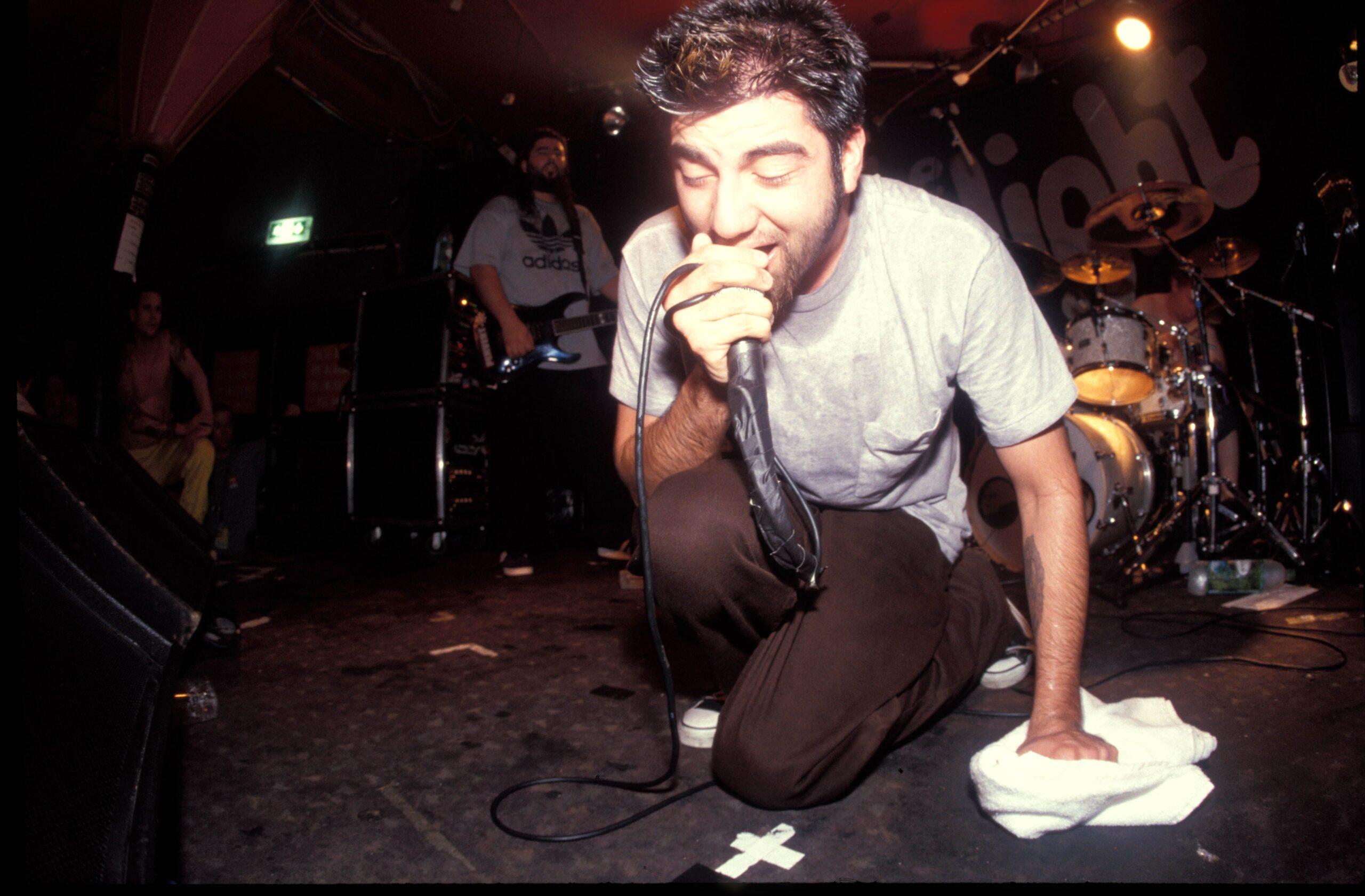

Go Get Your Knife: The Oral History of Deftones’ ‘White Pony’

The story of how the Sacramento band pushed past the nu-metal label and delivered a classic that reverberates to this dayIn between the eras of WWE-style rap-rock and East Coast punks discovering their parents’ vinyl collections, Deftones carved a niche on 2000’s White Pony that mixed sex and violence unlike any band before them.

“White Pony was the extreme version of [us following our instincts] and going left of center,” singer Chino Moreno says. “We went in with no preconceived ideas of what we were going to make. We knew what we didn’t want to make.”

What the Sacramento-based band didn’t want to make was the aggressive mix of hip-hop, howling vocals, and heavy metal guitars coined “nu-metal.” The genre included bands like Korn, Limp Bizkit, and Papa Roach. Before White Pony, Deftones were thrown in that category, too, much to their disdain.

“I wanted to go left [of nu-metal], not because I felt we were better than these bands,” Moreno says. “I wanted our band to stand on our own two feet. Nu-metal was at its peak. It’s in the name—nu-metal—it’s going to be old in time. Eventually, it did die. My whole idea was when that ship does go down, I don’t want to be on that motherfucker. We tried to distance ourselves as much as we could, and the best way to do that was by following the path we were on.”

The band had already shifted from the rap-rock styles heard on 1995’s Adrenaline to a dreamier, emo-infused aggression on 1997’s Around the Fur, which included the sleeper hit single “Be Quiet and Drive (Far Away).” By 1999, Deftones were ready for another change.

“I was thinking to myself, ‘I don’t want our records to be predictable,’” Moreno says. “I thought the weirder the music was [on White Pony], the funner and better it was going to be.”

Twenty years after its release, White Pony is still the Deftones album, Moreno says, and he’s not wrong. Musically, you can hear the band’s collage of influences, the very reason then-A&R rep Guy Oseary signed the band to Maverick Records. There’s drummer Abe Cunningham’s love of the Police drummer Stewart Copeland on “Digital Bath.” Bassist Chi Cheng’s off-kilter rhythm rolls throughout “Korea.” Guitarist Stephen Carpenter shreds with the best of them on “Elite.” Turntablist Frank Delgado brings a cinematic atmosphere to songs like “Teenager.”

“We were all into a whole bunch of music,” Delgado says. “We were trying to put it all in there without looking like bozos. Maybe we didn’t know it would pay off in the long run, but in our heads, we were like, “Wait till people hear this.’”

Lyrically, the songs are weirder. Moreno kicks the album off, shouting “Fuck, I’m drunk,” on the opening track “Feiticeira,” which is sung from the point of view of someone being kidnapped. There’s a scenario involving electrocution on “Digital Bath,” car sex on “Passenger,” and haunting, eerie moans on “Knife Party.” Such content came from Moreno getting the courage to step outside of writing songs entirely about his feelings.

“I learned how to write lyrics listening to [The Cure’s Pornography]. I had the cassette, and it didn’t have lyrics in the booklet. I would listen to songs, rewind them, and write down what I thought [lead singer Robert Smith] was saying,” Moreno says. “His stuff was abstract. There was fantasy in it. When we started recording White Pony, I started to venture more into that fantasizing. It made me feel free. I could expand the songs, instead of having to make everything about what I’m actually doing or feeling at that moment.”

Commercially, White Pony is the band’s biggest seller. Released on June 20, 2000, the album debuted at no. 3 on the Billboard album chart, selling 178,000 copies in its first week before being certified platinum in July 2002. The album also has the band’s biggest hit, “Change (in the House of Flies),” which peaked at no. 9 on Billboard’s Mainstream Rock charts and no. 3 on the Alternative Airplay charts.

The result is what singer-songwriter, guitarist, and frequent Deftones collaborator Jonah Matranga calls a masterpiece.

“White Pony is somehow really heavy, groovy, sweet, and sexy—it’s everything at once,” Matranga says. “Everything worked.”

To celebrate the 20th anniversary of White Pony, the band and others discussed its writing and recording, the band’s infighting and battles with the label, extracurricular activities, and the album’s significance today.

Part 1: “He called us ‘The Tones’”

With the relentless schedule of a two-album cycle behind them, Deftones went to work on their third album in April 1999. The band knew it would be called White Pony, a name that alludes to drugged-out nightlife scenes as much as it is a signal flare for a band that wanted to go against the nu-metal grain. They had a vision and ideas for how it would sound, but not much music. Excited for the future, the band started discussing the album with potential producers and collaborators, who all looked at them as if they were nuts.

Frank Delgado, turntables/keyboards: We had the name right out the gate—“the white pony”—it was about sticking out from the pack. It slipped off the tongue, and we just ran with it.

Chino Moreno, vocals/guitars: “Korea” was the only song we had. We were inspired by a lot of DJs and what they were doing at the time. The one thing we wanted to do was have big drums and that low-end sound. We wanted to make it more cinematic and include Frank more.

Delgado: I would just hang out with a bunch of dudes in their rehearsal space, and I would play music in between them jamming. That was like ’92. It just went from there to them asking me to come up to Seattle and hang and put some stuff in some songs. [Bassist] Chi [Cheng] was very supportive of me coming into the band, and it kept progressing to finally they were like, “Quit your fucking job.”

[Before White Pony], I was DJing a small gig, opening for DJ Shadow at the Cattle Club. Me and a few guys from the band were there. We were like, “We’re gonna hit Shadow up to remix our record.”

We hadn’t even recorded it. We hadn’t even written it. He looked at us like we were fucking crazy, but we knew we were on to some shit.

Abe Cunningham, drums: We did our first two records with [producer] Terry Date. By the time we were getting to the third record, he said, “I encourage bands to go try somebody else and see what you can come up with.”

Terry Date, producer: I didn’t want them to feel stifled by one person. I wanted to make sure that if they go in a different direction with someone else, I’d be happy with that. It was a conversation [Soundgarden singer/guitarist] Chris Cornell and I had once or twice. [Cornell] didn’t think it was healthy for a band to work with the same person too much.

Cunningham: We did meet with Jerry Harrison from Talking Heads, and Rick Rubin. Rick would come out to our shows over the years, but he would just call us “The Tones,” you know, because he had that whole funeral thing for the word “def.” He wouldn’t say the word “def.”

Moreno: I met with Rick over breakfast, and he was like “What are the songs about?” I was like, “I don’t know.” I just had a vision of what I wanted it to be on a larger spectrum than just a heavy rock record. He didn’t get it. His process is more of you play the song on an acoustic guitar before you record it. We were never that type of band. We make some sounds, and the sounds inspire where the lyrics and everything else goes. It wasn’t really a match.

Cunningham: All these people were great, but the whole meeting with someone and having to get comfortable with another person in the studio … we were already on to something, and Terry Date was right there, ready to go.

Moreno: Terry is a great engineer. His hands are on the board. I’d be like, “I’d really like for this to have this cool trail-off thing,” and he’d be like, “What?” So then I’d bust out a Depeche Mode record and show him what I was talking about. He’s like, “OK, gimme two seconds.” [Makes clicking noises.] And there it is.

Date: I’m the first to admit, and they’re a close second, to accuse me of not quite nailing the low-end part on the first record. I think we nailed it on the second record and especially on White Pony.

Part 2: “When I heard the band name, I thought it was going to be ska or reggae”

After touring with Ozzfest ’99 in the summer, guitarist Stephen Carpenter moved to Los Angeles, where the band would later complete the album. The rest of the band stayed in Sacramento, and Moreno began to write songs on guitar.

In August 1999, the band headed to the Plant, in Sausalito, California. The sessions took longer than expected. By early 2000, the band moved operations to Los Angeles as Date mixed songs and Moreno worked on vocals. The 10-month period from recording to the album’s eventual release was filled with parties, marathons of Tony Hawk Pro Skater, and tension between Carpenter and Moreno.

Carpenter: Back then, my thought was, “Isn’t it lucky that you get to learn how to play guitar in your signed act?” As long as he’s been playing guitar, there’s this constant story that’s been projected that we’ve been at odds with each other. There’s about 98 percent of the time when we’re not at odds with each other.

Cunningham: It was way more love than what’s been talked about. I think our best music has come out of that battle between the two of them.

Moreno: I don’t think any of us had a clear idea of where we wanted to go, but it was a thing where Steph would say, “Check this thing out,” and I’d say, “Rad, well, check out this song.” We would build on each other’s ideas. We were outdoing each other, not to control anything, but just to escalate the record.

Jeff Irwin, guitars in the band Will Haven: The stuff between Steph and Chino was blown out of proportion. They were just trying to one-up each other, which is what they should be doing. That’s how you make the best record you can make.

Those guys have been best friends since they were 13, 14, 15 years old. They are a dysfunctional family. They’re brothers. They don’t even have to talk to each other. They know exactly what each other is thinking.

Date: How many bands can you think of where the singer and guitar player butt heads, especially when the singer starts playing guitar and steps into the guitarist’s territory a little bit? There was some of that going on, I’m sure.

On top of that, these guys are extremely passionate, emotional guys. They feel very strongly about everything they do. The best records I ever worked on were ones that had conflict of some kind—some vibe that took things to a higher level.

Moreno: Half the record was written in the studio. We definitely spent more money than we should have because we wasted a lot of studio time by not being prepared when we went in there.

Date: One of these days, I’ll sit down and remember how long it took, but … I’m guessing it took six months, on and off. Maybe a year? How long did they say it took?

Moreno: We spent a lot of time in the studio, wasting time. We’d have Mimosa Mondays. It’d be 10 a.m. on a Monday, then we’d order some food, maybe go mess around with some music, go for a bike ride.

We were living that time to its fullest. It didn’t feel like a job, doing that record. We had fun the whole year or so it took. I think it was when the first Tony Hawk came out.

Cunningham: [Tony Hawk Pro Skater] was the worst for Terry Date.

Date: I think the best decision the studio owner at the Plant ever made was to put Tony Hawk on a big screen in the lounge. There were so many hours of studio time burned because we weren’t doing a damned thing.

Carpenter: Terry would give us grief because we were crushing on that all the time. Terry’s like, “We’re in the studio, guys. This costs money.” We’re like, “Whatever, we’re playing this video game.” The best part was just acting a fool and stringing all types of tricks together. You didn’t even have to know what you were doing.

Cunningham: We were out of our minds, having a blast, thinking we can do whatever we want. We thought, “We don’t care if we’re going overbudget. We’ll pay it back.” Terry Date would be so pissed. His glasses would steam up. We would do it on purpose. He would come in the lounge, biting his lip. We were like, “Let’s do whatever we can do to get Dad pissed.”

“The best records I ever worked on were ones that had conflict of some kind—some vibe that took things to a higher level.” — Terry Date

Date: The music goes down pretty quick, but it doesn’t take shape until the vocals are in there. Chino wouldn’t know until after the music was done. That’s what he would use to inspire him to write the words.

Moreno: Two days after New Year’s in 2000, we moved everything down to Los Angeles and lived in this big mansion in the Hollywood hills—that was wild.

Cunningham: They had named that house “The Devil House.” It was “The Devil House.” Something was definitely there. I would wake up in the middle of the night with pressure on my lungs. It was the worst. It was a frightening place.

Moreno: It could have been the drugs, but I just got scared and was like, “Fuck it. I’m gonna stay in a hotel.” But it all worked out, because if I was trying to stay on a work schedule, it wasn’t the best place to be.

Carpenter: Fools got wasted. Did Abe tell you about stabbing himself in the head?

Cunningham: I got stabbed in the head.

Carpenter: I wasn’t there when it happened. It was days later, and they were talking about it. Abe was laying in bed, and he just rolled onto a knife somehow. I was like, “How does that even happen?” I know of the physical action of stabbing, but I was like, “Holy shit, dog, you could have killed yourself.”

Delgado: Lots of partying, blood. … You’re in Hollywood, doing crazy shit. You’re at speakeasies at five in the morning, out in Compton. Shit just happens, you know what I mean?

Moreno: We were getting wild every night. I remember more of the other stuff than the tracking. To be young, I guess.

Date: I used to always mix at a place in L.A. called Larrabee Studios, and we did a bunch of the vocals there.

Moreno: The first song I recorded vocals on, “Feiticeira,” I remember specifically being in the vocal booth. While I was singing, I felt like I was inside the song. I was imagining being inside the story, about someone getting kidnapped and thrown in the back of a trunk. It felt really surreal.

Walking out of there, I remember thinking to myself, “This is neat.” I don’t know I ever tapped that deep into a song. That was the first stepping stone for finishing a song, lyrically. From then on, I felt like the ball was rolling.

Date: “Knife Party” was the song that got me going because it had so many cool things going on in it. I remember [guest vocalist] Rodleen [Getsic] doing her parts and how we put that all together. None of us knew what [Rodleen] was going to do.

Delgado: [All the collaborations] happened organically. It all just kind of fucking fell into our laps. I remember Rodleen. We didn’t know who she was, and Chino met her in the kitchen [at Larrabee].

Rodleen Getsic, “Knife Party” guest vocalist: I had gone [to Larrabee Studios] because a friend of mine and amazing bass player, Rob Wasserman, was doing his solo record. I was going to check out his recordings.

There was this lounge/greenroom-type area upstairs at Larrabee, and everyone was taking a break. Someone put in a cassette recording of a show I had just played in San Francisco. Chino heard it and brought me aside and said, “Hey, will you sing on our record?” I said, “Well, I’m sure it’s possible. If it hits my soul, I can do it.”

When I heard the band name, Deftones, I seriously thought it was going to be a ska band or reggae.

They started playing a little bit of the song, and right away, I was like, “Stop it, let’s press Record. Let’s go.” I was feeling the song right away in my soul. I knew something was going to come out of it. It wasn’t very long in the recording booth. It was improvisational and spontaneous. It was just a few takes. It all happened very quickly.

Date: In spite of all the pressure from the label, we never thought “What’s the first single going to be?” We were thinking in terms of the songs being a cool experience. That being said, we all knew “Change” was really good.

Cunningham: Chino started singing lyrics over “Change,” and we were all sitting in the control room. Hearing that song come together in its rough form was one of those moments. We knew we were on to something. It was an amazing feeling.

Jonah Matranga, singer-songwriter: We had already done some stuff together, and me and some guys from Far were down in L.A. We just stopped in. I remember “Change” was up. Chino’s technique was to listen to the song over and over again, just kind of mush-mouthing and seeing what was there. I did a couple rounds of that, and he did a couple rounds of that. None of my ideas ended up being there, but it was sweet. I just adored doing that with friends.

Delgado: Writing those songs as a whole, it’s always hard. It’s not easy, trying to get five different heads on the same page. You can make something by yourself that sounds really cool, but the whole point is getting everyone involved and driving through it.

Date: “Rx Queen” started out at the end of a night, probably a Saturday night after a long week. We started having some beers, probably a lot by that point. Chino used to love to go out and sit on Abe’s drums and play while they were mic’d up. It drove Abe crazy. Chino started playing something, and Abe went out and started hitting parts of the drums and mic stands while Chino was playing.

“We were out of our minds, having a blast, thinking we can do whatever we want. We thought, ‘We don’t care if we’re going overbudget. We’ll pay it back.’” — Abe Cunningham

We were still in there with tape on, and I started recording. I recorded a bunch of these little grooves the two of them were doing together. I had my assistant take those, chop a section and make a loop out of it. Chino wanted to slow it down, and Stephen wanted to speed it up. I had my assistant make a fast and slow version. I told them to throw some stuff on it, and let’s see which one wins. Chino won on that one.

That song was totally created out of too many Coors Lights. It was an out-of-nowhere song.

Moreno: When we were in L.A., [Tool’s Maynard James Keenan] was writing and recording with A Perfect Circle. “Passenger” was probably one of the last songs I recorded vocals on, and I mentioned to him something about getting up on it. He was like, “Yeah, sure.”

He came by the studio, and it was just me, him, and Terry was in there at the board. We had a pad of paper, two pens, and we’d play the song. I wrote the first line, “Here I lay,” then I gave him the pad. He wrote the second line, “Still and breathless,” then I take the pad back … boom boom boom.

It was a pretty organic collaboration. It wasn’t like, “Oh, I wanna get the guy from Tool on the record.” It was someone I was hanging out with a lot, sharing a lot with. We were both in the writing state then. The way that we wrote, line by line, was a pretty rad way to collaborate, especially these days when it’s over the internet or whatever. Being in that moment, in the same room, was really something special.

Part 3: “I totally forgot ‘Back to School’ was a second single”

When the album was complete, the band was confident in the material. Maverick Records was equally excited, bringing in Frank Maddocks, a then-new hire from its parent company, Warner Bros. Records, to work on the album’s iconic look and feel.

While the label wanted a rap-rock-styled single, the band fought to release “Change,” which flew up the singles charts in May 2000. After White Pony’s release, the label pushed for a radio-friendly take on the epic closer “Pink Maggit.” The new song, titled “Back to School (Mini Maggit),” was released in October 2000 and thrown on a reissued version of the album, to the band’s displeasure.

“Back to School” wasn’t a hit, topping out at no. 27 on Billboard’s Alternative Airplay chart and no. 35 on the Mainstream Rock songs chart.

After a fall tour that was cut short, the White Pony album cycle was ending. The band received good news, however, when the song “Elite” was nominated for and then won the Grammy for Best Metal Performance. Bigger concerts followed, as did “the dark days.”

Frank Maddocks, art director/designer: My idea was to bring a clean, minimal, and sterile design approach. I don’t think a lot of people were taking that approach, at least not in this genre of music. It was interesting to marry these clean images with what was perceived at the time as a very aggressive kind of sound. I liked that push-and-pull.

We started putting the pony out into the world on posters and stickers six months before the album was released. There was a bit of a propaganda aspect to it. We wanted to start the conversation where people would be like, “What’s this? What’s coming?”

Amongst people who were already into the band, it was a heavily anticipated album. Here I was at Warner Bros., and I’m working on a Maverick project. The people at Warner Bros. didn’t know too much about the band. I don’t think people had a sense that the record would be as iconic or as big as it was until they heard it. Then, when they did hear it, they were like, “Holy shit, this is next-level.”

I was fortunate enough to get a copy of the album before it was released, and I was just blown away. At that point, the band’s progression was already evident from Adrenaline to Around the Fur, but White Pony? I remember listening to that, and I couldn’t believe it.

“Writing those songs as a whole, it’s always hard. It’s not easy, trying to get five different heads on the same page.” — Frank Delgado

Irwin: At first, I remember thinking, “This sounds like Depeche Mode on steroids.” After I got to “Knife Party,” I just stopped the record. I called Chino, and I had to tell him like four times, “Dude, this fucking record is sick.” I couldn’t comprehend what the hell was going on at that moment.

It was funny to think about, because Will Haven had gone on tour with them after Around the Fur, and I had heard those songs about a million and a half times. I heard “Knife Party,” and I’m like, “Is this the same band?” To me, these guys are a bunch of clowns; so, for them to be in the studio, writing this, it’s like, “Where did this come from?” I’m still floored by that record.

Aaron Harris, drummer/composer/sound designer: [Harris’s former band ISIS] was on tour with Dillinger Escape Plan around that time. During a sound check, the sound guy put on “Digital Bath.” I remember thinking, “This is awesome. Who is this?” The sound guy tells me it’s Deftones, and I was like, “What? Really?”

Prior to that, I didn’t pay much attention to them, because I assumed they were part of the nu-metal scene that I wasn’t that interested in. Once I heard that song, though, I checked out the album. I loved it. Everything about it. The whole thing became my soundtrack for that year.

Lorraine Ali, journalist: White Pony had the same emotional quality as listening to deeper stuff that I liked from the ’80s, like some of the Echo and the Bunnymen stuff.

[Deftones] lifted up a genre that was rolling downhill fast. Think about it: Music got really bad toward the end of [the ’90s]. There were boy bands, and the flip side of that was Limp Bizkit, who were just as bad. Deftones were the saving grace after [nu-metal].

Matranga: I was in England, on tour with some friends. I had an advanced copy or something. It’s one of those things I can remember the exact first time I heard it. It’s a masterpiece. The drums on “Digital Bath” … that’s such a fantastic groove. It’s pretty much everyone’s favorite song off that record.

Date: Typically, I don’t listen to the records I do when I finish because I’ve heard all those songs thousands of times, and all the flaws are so glaringly painful for me. But there are a number of things about White Pony … like “Digital Bath,” the drum sound at the beginning of that song is always something I’m going back to as a reference point for things.

For the record, and not to quote them, but I was a passenger. It was a lot of skill on Abe’s part, and it was probably luck on my part.

Moreno: We turned the record in, and the label was stoked on it. When it came time to pick a first single, me and Guy [Oseary] got into a back-and-forth. I thought “Change” should be the first single. They wanted something a little more aggressive. I knew [“Change”] wasn’t the most aggressive tune, but I knew it was the best song on the record. I wanted to come out guns blazing. Everybody agreed to it, and the record came out.

“The people at Warner Bros. didn’t know too much about the band. I don’t think people had a sense that the record would be as iconic or as big as it was until they heard it.” — Frank Maddocks

Shaun Durkan, singer/bassist in the band Weekend: I camped outside the local record store on a Tuesday, because that’s when new music came out back then. I think some of the songs had leaked on Napster, and I think I had “Digital Bath.” That, alone, blew me away. I was like, “Oh my god, if the rest of the record sounds like this, this is going to be fucking mind-blowing.” For the most part, it does.

Dominic “Nicky” Palermo, vocals for the band Nothing: White Pony blew my mind. That record wound up being one of the closest things that existed that I envisioned [Nothing] could sound like. It was this unreal blend of the heavy and ambient with smooth, lush, landscaped vocals peppered in. I truly remember listening to it and thinking, “Why even bother?”

Cunningham: The record was done and perfect in our minds. Then, we were asked by the label to try and make a hit, and that became “Back to School,” which was later tacked on. We were furious because it opened with “Feiticeira” originally, and it was exactly the way we wanted. It was our perfect baby, and they wanted us to add more to it.

Delgado: I totally forgot that “Back to School” was a second single. That shows you how much I gave a fuck about it.

Moreno: I remember Guy calling me and saying, “This chorus on the last song (“Pink Maggit”) … that’s a hit chorus. All you gotta do is write something a little more upbeat on it. Why don’t you rap on it, man?” I was like, “Hell no. We just made a statement record, and you guys all loved it when we put it out a few months back.”

Going to record [“Back to School”], I was like, “All right, I’m going to show [Guy] how easy it is to make a simple, formatted, verse-chorus-rap-bridge song.” I sent it to them as quickly as possible so they could be like, “Wow, they did this that quick?’ They got it, and they loved it. I thought it was so-so.

Delgado: The whole thing left a bad taste … we all knew it. We were playing ball, you know what I mean? There’s a give-and-take in this business; you learn that eventually. We didn’t want to be complete assholes, but we’re like all right, we can do this. I had suits practically telling me what I should do in the song.

I recall not going to the studio that day so I wouldn’t have to do it. I just didn’t show up. I don’t think we helped much after, too. I don’t think we played it. There was a whole stretch when we didn’t. That doesn’t help a single.

Moreno: If I could go back, would I say no? I don’t know. It is what it is now. I’m not completely bummed about it. Now, if you ask me what version of the record I prefer, obviously [my answer is] the original without that song on it.

Irwin: I give Chino all the props in the world. Chino was like, “Yeah, but I don’t like it. I don’t want to fucking rap. I don’t want to be a rap-rock band.” I got it. They could’ve cashed in, and they eventually put it on the record, but for him to say, “Fuck you, I’m gonna go this artsy route.” I think that’s fucking awesome.

They were separating themselves from everybody. It was a bold move, and it made them who they are. I don’t think it made any difference [to release “Back to School”], though. “Change” was a way bigger hit.

Delgado: [The Grammys were] a trip, man. When we got to our seats, which were one level up from the floor, we were like, “Oh yeah, this is going to be a people-watching thing.” When they called us, we were like, “What the fuck?” We had to jump down onto the floor to walk up and get the award.

That win solidified our mind-set. The label and suits were all worried about “Back to School” and the other bullshit, but look at how we won this for something they had no part of.

Carpenter: We played some good shows, man. There was the Waldrock Festival. That was the most wasted, faded, off-the-hook, destroyed show ever. We were at our highest point ever. We were living off the hook.

A big moment for me was when we got to play the Rock in Rio Festival in Brazil. There were over 200,000 people there. I had never been to a show like that. There were just people as far as you could see. We were on the main stage, and it was massive. It was my great idea that we should spread ourselves across the stage, instead of being all together in the middle. It ended up being a bad idea. We were too far apart. I’ve never been really nervous on stage, for the most part. That day, I had involuntary shaking for the entire show. It was bigger than anything I could imagine. All I could hear was myself, and I was thinking, “I sure hope everyone is playing along with me right now, because I cannot hear them.”

Delgado: It was after White Pony when the suits started poking their heads in. Our response was, “We did it without all of that shit, so just leave us to our accord.” But that’s usually not how it works.

Carpenter: We would consider that time the beginning of what was becoming the dark days—battles with drugs. I’ve always been a pothead, going through all these years. I didn’t recognize other people when they were in their issues. I was shocked when we dealt with it all and confronted it all. Once we did, the thing that unified us was there again, and the bond was going through it.

Date: A lot of the darkness that they talk about, they didn’t let me see. I was the dad, and they were keeping it from the dad, you know?

But during the recording of the self-titled album, Chino was having trouble with words. I do remember sitting for a long, long time. I would loop the song to him. He had a separate room that music would go to, and the lights were off in there. I would loop the song to him, and whenever he would start singing, I would hit Record and keep it.

I just remember looping one song 12 hours a day, six days a week, over and over, while he was trying to come up with words. That was a whole week of work right there. That had never happened before.

Part 4: “Cheng was like all of us”

A self-titled fourth album was released in 2003, followed by 2006’s Saturday Night Wrist. Both albums were fraught with delays, increased drug use, and growing tension among band members.

That tension would cease as the band began to work in 2008 on Eros. However, tragedy struck when Cheng was involved in a car accident, leaving him in a minimally conscious state. In 2013, Cheng died after falling into cardiac arrest.

Delgado: He was Chi, man. We used to make fun of his rhythm, but he always had a lot of love for people. He put 110 percent into it all of the time. That’s what we’re all trying to do.

Date: Chi had this cool factor that everybody liked. He had a calmness about him that settled things down. He never got too out of control about too many things.

Carpenter: Cheng was like all of us. He wasn’t going to bow down to others. He contributed and brought himself to the thing.

Trust, like brothers, we all had our real battles, struggles and arguments, but none of it superseded the way we actually enjoy each other. We appreciate each other as individuals and as a whole, and we see each other as a whole.

“There were boy bands, and the flip side of that was Limp Bizkit, who were just as bad. Deftones were the saving grace.” — Lorraine Ali

Irwin: Chi has always been a badass. If Chi were still alive, he’d still be in that band. That’s a testament to how much they love each other. Being in a band sucks so hard, especially on that level, but they trust each other. They’re gonna have fights and bicker, but they’re normal guys.

You look up to them on stage, and they’re not wearing makeup. They don’t have crazy hair or costumes. They’re just regular guys who play fucking rad music. They can’t date themselves. They’ve never been a hype show. They just get up on stage in everyday clothes and fucking kill it. They go out there and just destroy you with their music.

Part 5: “It’s the little horse that could”

Before heading into lockdown due to COVID-19, Deftones were working on their ninth album, and their first with Date since 2003. The sessions were just like old times.

Of course, with a new album on the horizon, the question is always, “Does it sound like White Pony?” Looking back on that third album, everyone involved realizes how important it is, how that success can’t be simply replicated.

Cunningham: We just got done with this new record with Terry, and we hadn’t made a record with him in quite some time. When we were discussing how to record it, [we mentioned that] we had been tracking to a click, laying down rough guitar.

Terry looked at us and said, “You can do that if you want, but you know what you guys are gonna do? You’re gonna go in there and play like you always did before—the five of you—together, no clicks.”

And we did it. It was like, “Woah, man, we can do this.” It was very reaffirming.

Date: I’m amazed that a band can do what is essentially their 10th record and sit in a room together without killing themselves.

We’ve been like a family since the mid-’90s. Even when they go off and work with other people, we’re always in contact. There was no break in the relationship at all. I consider them my brothers. No matter what happens at any time in the past or the future, our relationship is going to be the same.

Getsic: [White Pony] is magic. There’s no other record like it, and there never will be again.

Maddocks: I can’t tell you how many people in bands have cited that as being really influential in their upbringings and careers. I’m so appreciative of that and stoked that people would mention me.

At the moment, you don’t really know if something is gonna be big. You can do great album art for bands that no one has ever heard of, and people don’t talk about it. I’m fortunate that my art is married with an iconic record. We could have put a white horse on something from a band you’ve never heard of. It was just the right place at the right time.

Mantrega: White Pony has lasted because it’s fucking incredible. Every record since then, to me, is basically informed by that combination of riffs and dreamy stuff. If they had released that record earlier in their career, I don’t know if it would have had the same impact.

Ali: No matter how you want to rewrite it, Deftones did something very different. They went out on a limb, and they did something that probably should have never sold, and it did. I don’t recall anyone coming along after them that did what they did.

Cunningham: It’s funny because it takes one small thing to throw everything off-course, and it could go an entirely different way. We were on to something. We finally felt comfortable enough to add different elements and just say, “Fuck it, let’s go this way and see what happens.” I’m glad we did, and I think that’s why we’re still around to this day.

It’s the little horse that could. It’s running free, but it’s a little bit older of a horse these days. It’s an amazing horse. That’s my little buddy. It’s the album that allowed us to be who we wanted to be and set us up for some sort of a career.

Moreno: Whether we like it or not, White Pony is the record that defines us. Everything about it fell into place.

Matthew Sigur is a writer, comedian, and musician based in Chicago.