The Perfect NBA Marriage

As brand-new Big Twos sprouted all around the basketball map last summer, Damian Lillard and CJ McCollum doubled down on their long-term relationship. But can longevity lead to a title in today’s ever-changing NBA? The Trail Blazers backcourt mates discuss the keys to their partnership, as well as the obstacles that may lie ahead.Last summer, as a frenetic period of free-agent signings and trades began to reshape the power structure of the NBA, Damian Lillard and CJ McCollum texted each other with running commentary about the latest developments. This was nothing new; they’ve been in near-constant communication for the seven years they’ve been playing basketball together in Portland, including almost every day of the offseason. What felt new was that the landscape of the NBA was transforming all around them: A league dominated by power trios and superteams was downsizing into a league defined by power duos.

With each new signing, Lillard said, “We were like, ‘Ohhh, that’s interesting.’”

They had their own thoughts about which of these pairings would work out, and which seemed more perilous. Lillard found the team-up of Kevin Durant and Kyrie Irving a fascinating match; when Lillard heard that Russell Westbrook and Paul George had both been traded away from Oklahoma City—just months after Lillard hit the dagger of a shot that knocked the Thunder out of the playoffs—he thought, That’s kind of weird. “It was just two seasons,” he said, “and now they’re both gone?”

Lillard told me this last fall, on the eve of the strangest season in NBA history. Back then, he and McCollum seemed almost impervious to the league’s free-agent turbulence. Last July, as LeBron James and Anthony Davis, Kawhi Leonard and Paul George, Russell Westbrook and James Harden, and Kyrie Irving and Kevin Durant were entering into tantalizing new professional partnerships, Lillard and McCollum quietly and purposefully agreed to sign long-term contracts with the Trail Blazers within weeks of each other, which locked them both up through the 2023-24 season. There was no seven-year itch, even with all the movement occurring all around them.

It doesn’t matter to Lillard that he and McCollum are often seen as a pair of score-first guards who may be too similar to win an NBA title together, just as it doesn’t matter to McCollum that Lillard will always be viewed as the alpha of the pairing. And it doesn’t matter to them that a good portion of the league viewed the Blazers’ appearance in last season’s Western Conference finals as something of an anomaly that they’ll be hard-pressed to repeat in the compressed format of the NBA’s restart, which is being held in a bubble environment in Orlando because of the coronavirus pandemic. The Blazers will need to go on a protracted run just to make the playoffs—and if they do make it, they’ll then need to find a way to get past some of those newly formed superstar duos.

Lillard and McCollum decided to stick together mostly because they enjoy playing with each other. And a year after they signed those contract extensions, with the league, the city of Portland, and the country facing unprecedented turmoil and uncertainty, Lillard and McCollum’s friendship still hasn’t wavered. It feels increasingly like the most enduring partnership in the NBA. That’s never been clearer than it was on July 15, when Lillard prepared for a quiet acknowledgement of his 30th birthday in the league’s Orlando bubble—and McCollum refused to let it pass without a celebration.

McCollum decorated the door of Lillard’s hotel room; he reserved a private room where the entire Blazers team could safely gather. He reached out to Lillard’s fiancée to ask about his favorite foods, and put together a menu of lemon pepper wings, short ribs, lemon cake, and more. He created a special drink for the occasion, and ordered wine and champagne. None of it was necessary, of course, but for McCollum, it mattered.

Lillard and McCollum have taken care to align their timelines in contract talks (Lillard has a player option after 2024, when McCollum’s contract ends). “We’ve just always tried to match our years up,” Lillard said. “So that we’ll both be free at the same time. If there’s ever a change of heart, then we can make that decision together.”

Somehow, over the course of those seven years as teammates, Lillard and McCollum have remained close friends, real friends—not just locked into a marriage of convenience. They’ve been known to take vacations together; even their mothers have become close. They’ve been in constant contact since McCollum was in college at Lehigh and Lillard was a rookie out of Weber State who recognized a kindred spirit from a small college. When Lillard was filming a music video for his hip-hop album last summer, McCollum happened to be in Los Angeles at the same time, so he made an appearance in the video.

Lillard can’t say for sure, but of all the high-profile duos in the league, he thinks it’s likely that he and McCollum have the closest personal relationship of them all. McCollum believes the same. “Usually when you hear something’s going on [between two teammates], then something’s going on,” McCollum said. “But you don’t ever hear anything about the two of us for a reason.”

Our legacies are definitely tied together. People will remember.CJ McCollum

You didn’t hear much during a turbulent regular season, even as the Blazers limped and struggled before Lillard almost single-handedly lifted them back into playoff contention. Part of their silence in the face of adversity may be a benefit of laboring in a small media market like Portland. But it’s also because Lillard and McCollum have spent years cultivating their relationship as a duo, which is perhaps the deepest “NBA Marriage” of the modern era.

“You can tell when guys don’t get along,” McCollum said. “The body language says a lot. It’s obvious. But there’s a mutual admiration with us because we knew each other before we even got in the league.”

And yet, larger questions loom: Does that personal admiration really make a difference? Or are modern NBA marriages simply about pairing A-list talents together and hoping for a short-term breakthrough? In an era when relationships are so often defined through the prism of social media and public perception, how much does the longevity of a duo’s relationship really matter?

These are the questions awaiting Lillard and McCollum as they advance into the midpoint of their careers. In a way, their partnership feels almost quaint, like a throwback to a previous era, when the NBA wasn’t defined by the transactional value of its player-engineered team-ups. In a way, it also feels unique to small-market Portland, which has formed a team that is almost a feel-good antidote to the Jail Blazers of the late 1990s and early 2000s. But how much does all that mutual admiration really impact their ability to win a championship together as they advance into the most crucial seasons of their careers?

“Our legacies are definitely tied together,” McCollum said. “People will remember.”

All of that explains Lillard’s response to McCollum’s birthday arrangements within the bubble. After his teammates sang “Happy Birthday,” Lillard made a simple ask regarding their efforts within the bubble.

“Let’s not waste our fucking time out here,” he said.

When I asked Lillard his all-time favorite NBA duos, he started in an unexpected place: Vince Carter and Tracy McGrady, cousins who played all of two seasons with the Toronto Raptors in the 1990s before McGrady left for the Orlando Magic. “The fact that they were related and played together? I really liked that story,” Lillard said. “Even though they didn’t have real moments together.”

When Lillard was younger, he gravitated toward the players who seemed (at least on the surface) to get along famously, like Steve Nash and Dirk Nowitzki or Isiah Thomas and Joe Dumars. By the time he took his own unlikely path to the NBA, he realized that was what he wanted: a partnership where two people can coexist side by side without rancor and without “trying to outdo each other.”

That’s what Lillard has with McCollum, and he admits that it’s been easier to build that friendship in a small market like Portland, with a couple of guys who emerged out of smaller colleges, than it might have been if they were both college stars landing in Los Angeles. They’ve had to overcome the same obstacles; they even both broke a foot in college, which helped them feel like kindred souls from the start. Lillard reached out to McCollum after hearing that McCollum suffered a nearly identical foot injury during his senior year to what Lillard had suffered two years earlier. McCollum began peppering Lillard with questions about how he rehabbed, and how he managed to come back and get chosen as a lottery pick coming out of Weber State.

“He was worried about his draft status,” Lillard said. “I was like, man, mid-major talent is not as much of a secret as it used to be. And they recognize that you’re one of those guys.”

Lillard was helping to build up McCollum’s confidence even before they became teammates. They kept checking in with each other, and as the 2013 NBA draft approached, it became more and more evident that McCollum could wind up in Portland. When he did, they immediately began working out together; they sat next to each other on the team plane, and still sit next to each other today. Their partnership felt disarmingly natural, both on and off the floor; they’ve spent an average of more than 27 minutes per game on the floor together this season, more than any other guard tandem in the league. While other teams tend to stagger the minutes of their stars, the Blazers have never done so, relying on the duo’s chemistry to carry them. And Lillard said that familiarity—both on and off the court—has allowed them to speak to each other in ways that many players can’t.

During Game 3 of the Blazers’ first-round playoff series against Oklahoma City last season, Lillard was struggling with his shot and begging the referees for foul calls in a hostile road arena. During a timeout, he started to complain, and then he locked eyes with McCollum, who told him to stop focusing on the officials, to stop being distracted.

If I can trust you on the court and off the court, it’s a breeze in the fourth quarter. There’s no animosity at all. I want him to have as much success as humanly possible, I want him to make as much money as humanly possible, and I want him to win. And I know he feels the same way about me.McCollum

“Remember who the fuck you are,” McCollum said to him.

They lost that game, but then won Game 4 by 13 points, and clinched the series in Game 5. If it had been anyone else talking to him that way, Lillard said, it might have escalated; it might have led to a confrontation, to a moment freighted with tension and ripe for social-media gossip. “If we didn’t have the relationship we do, it might have gotten ugly,” Lillard says. “It was exactly how my brother might talk to me. But when he said it, I didn’t respond. I was just like, ‘I got you.’”

“If I can trust you on the court and off the court, it’s a breeze in the fourth quarter,” McCollum said. “There’s no animosity at all. I want him to have as much success as humanly possible, I want him to make as much money as humanly possible, and I want him to win. And I know he feels the same way about me.”

Both Lillard and McCollum (who turns 29 in September) grew up in an era when the NBA built its cultural cachet through its duos. Pippen and Jordan, Stockton and Malone—when McCollum was asked the question about his favorite duos, those names started rolling off his tongue. So did the video game NBA Jam, which helped define the league’s best teams through the lens of their two biggest stars.

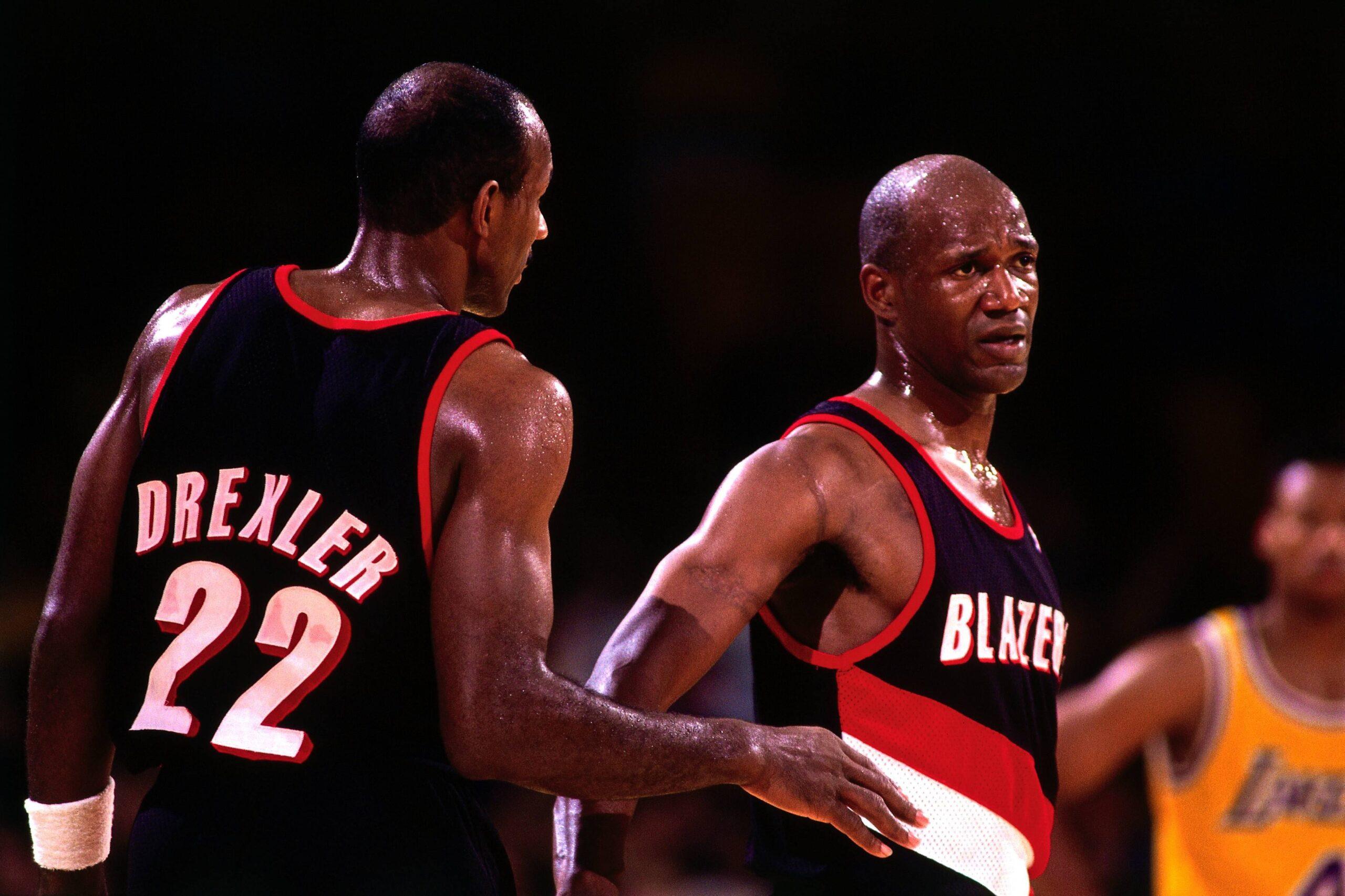

Back in the early 1990s, when NBA Jam took hold, the Blazers were represented by another pair of guards: Clyde Drexler and Terry Porter, who had spent nearly a decade together by the time they became a pixelated backcourt duo. The Blazers selected Drexler out of the University of Houston with the 14th pick of the 1983 NBA draft. Two years later, they unearthed Porter from the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, and chose him with the 24th pick of the first round.

“Man, I didn’t know Clyde at all except for seeing him with Phi Slama Jama,” said Porter, now the head basketball coach at the University of Portland. “We both started out on the second unit together.”

In 1986-87, they became starters, and won 49 games. In 1989-90, they made a run to the NBA Finals before losing in five games to the Detroit Pistons. Over that time, Porter had to learn how to coexist with Drexler, who played shooting guard but liked to handle the ball the way a point guard did. There was little doubt that Drexler was the alpha of the duo; Porter was fine with this, largely because he hadn’t even played Division I basketball in college, and he was willing to subsume himself in order to maximize Drexler’s prolific scoring abilities.

For years, they would discuss their basketball relationship at a breakfast spot in Portland where they were both regulars: How much should Porter handle the ball in the half court? When did Drexler want the ball in transition, early or late? (Porter soon learned that the quicker you could get the ball to Drexler, the more time he had to create his shot.) Gradually, they became friends. Which makes for a good story, but doesn’t necessarily make for a championship.

“It’s a nice little bonus if they’re friends off the floor, but I don’t think it has to matter at all,” says longtime NBA writer Bob Ryan. “It’s all about the personalities. It’s got to work with the personalities.”

For 10 seasons in Portland, Porter and Drexler flourished together, playing in three Western Conference finals and a pair of NBA Finals. But by the mid-1990s, their progress stalled: The Blazers were good, but not good enough to win it all. Something needed to be done, and in February 1995, with Drexler nearing free agency at age 32, the Blazers traded him to Houston, where he’d wind up winning a championship with his old college teammate Hakeem Olajuwon. In the fall of 1995, Porter signed with Minnesota. They are remembered as one of the great duos in Blazers history, but they also fell short of winning an NBA title, which is the same crossroad that Lillard and McCollum are poised at right now.

It felt like Lillard and McCollum broke through during the 2019 postseason. Lillard’s cold-blooded ability to finish off opponents, combined with McCollum’s ability to supplement Lillard’s scoring from long range, transformed them into one of the most lethal backcourts in the NBA. Before last season’s first-round series against the Thunder—a victory punctuated by Lillard’s epic winner in Game 5—they’d lost 10 consecutive playoff games. But in that series, and in the seven-game series win over the Nuggets that followed, they appeared to have transcended their previous struggles.

But then came the 2019-20 season. Injuries to big men Jusuf Nurkic and Zach Collins set the Blazers back for much of the campaign, and forced them to turn to veterans with more inconsistent track records like Carmelo Anthony and Hassan Whiteside. Lillard also missed six games with a groin injury, forcing McCollum to step up his abilities as a playmaker. It turned into the latest example of their collective ability to subsume their egos for the greater good. “I told him, ‘Just keep doing what you are doing,’” Lillard told McCollum, according to The Athletic’s Jason Quick. “‘Part of the player I am is I know how to figure out how to still be my best self without taking away from what you have been doing. So keep being aggressive, keep attacking, keep speaking up more. Keep being comfortable having the ball in your hands.’”

Yet for Portland to succeed in the bubble, it has to be about more than McCollum and Lillard continually evolving their dynamic. Now that Nurkic and Collins are back thanks to the protracted layoff, do the Blazers have enough to fend off Zion Williamson’s Pelicans, Ja Morant’s Grizzlies, and others to make the playoffs? And if they do, is simply making the playoffs enough for a team that now knows what postseason success tastes like?

Damian and CJ are at the point now where you ask, ‘What’s their legacy gonna be?’Terry Porter

With every year that it doesn’t happen in Portland, the question will arise: Can Lillard and McCollum ever win a title together, or is there a ceiling on their potential? And if that’s the case, would they be better off splitting up? It happened in Memphis last season, when Mike Conley and Marc Gasol parted ways after 11 years together; it could happen someday to duos like Joel Embiid and Ben Simmons, if the Philadelphia 76ers’ process doesn’t bear out with titles.

“Damian and CJ are at the point now where you ask, ‘What’s their legacy gonna be?’” Porter says. “For Clyde and I, it was always tough to get past those Laker teams, and Phoenix, and Utah and Houston. And for them, it’s no different.”

Part of the problem for Drexler and Porter was timing: They were great together—statistically, their best seasons rank among the most dynamic by a duo of teammates since 1976—but there simply were better duos who hit their peaks at the same time. The Lakers had Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; the Celtics had Kevin McHale and Larry Bird, who managed to surround themselves with a stellar—and relatively stable—supporting cast that complemented their inside-outside connection.

When the 1985-86 Celtics completed one of the greatest NBA seasons of all time, Bird was 29 and McHale was 28. By then, McHale and Bird had won multiple championships, and were surrounded by a cast of All-Stars and future Hall of Famers, from Robert Parish to Dennis Johnson to Danny Ainge. They were supremely confident that they could defeat anyone.

That was a different era, of course, with smaller salaries and less player movement; it was an era when the Celtics and Lakers and Pistons could hold together both their stars and their secondary players without them casting longing glances elsewhere. And that’s what McHale sees now: The money, he says, has inevitably impacted that level of stability. “It’s not just a duo,” McHale said. “It’s everybody that fits with them.”

That’s been the challenge for the Blazers, and for general manager Neil Olshey, now in his eighth season: How do you preserve the fit between Lillard and McCollum, and preserve the respectful “culture” that Olshey repeatedly touts (and that Lillard and McCollum reinforce), by bringing in the right people around them? Olshey spoke before this season, after the Blazers turned over much of their supporting cast, about bringing in “guys who buy in to how we do things in Portland”; but as of now, that approach hasn’t created a core that Olshey’s felt comfortable keeping in place around Lillard and McCollum. Part of that may be due to injuries; before Nurkic and Collins, there was the torn Achilles that ended Wes Matthews’s season and the Blazers’ title hopes. Part of it may be the failed free-agent splurge of 2016, when the front office may have overcompensated for the franchise’s inability to lure major free agents. And part of it may be the Catch-22 of building around two players with big contracts who haven’t yet proved that they can lead the Blazers to a title on their own.

That’s the frustrating part, McHale said, because the only answer for Lillard and McCollum “is, as crazy as it sounds, to say to themselves, ‘We’ve gotta do more. We gotta be better.’” While it’s true that Lillard and McCollum are only as good as their teammates make them, McHale said, it’s also true that this is now their team, and the team’s deficiencies get turned back on them.

When things go bad, that gets even harder—in large part, Lillard said, because the NBA is now defined by the drama of interpersonal relationships. Even if a pair of teammates like each other, they will still be weighed against each other; given the focus on free agency and trades, the anticipation of old partnerships breaking apart and new ones forming puts additional pressure on existing relationships.

“Sometimes the media likes to put stars against stars,” Lillard said. “They ask questions and debate questions on TV and make a conversation about stuff where you’re almost pitting teammates against each other. And that kind of starts the conversation, and people start to wonder.”

Perhaps the ability to transcend the ephemeral nature of the modern NBA will pay off eventually for Lillard and McCollum. Perhaps the pieces will fall into place around them, either in the bubble or in the years to come. But as Lillard hits 30, there’s increasing recognition that they’ve got only so much time left in both of their careers—as Lillard acknowledged on his birthday, there’s no more time to waste. For McHale and Bird, the decline began in the late 1980s, when both of their bodies began to break down.

“Sometimes it just isn’t your time,” McHale said. “I know one thing—we played the Lakers a few times, and shit, we couldn’t have tried any harder. But their best was just better than our best.”

Already, some of Lillard and McCollum’s prime years were swallowed up by the overarching presence of the Warriors dynasty. The rumors about the Blazers needing to trade away McCollum seem to flare every time the Blazers struggle, but Olshey has long insisted that’s never going to happen. And the team’s reluctance to do so banks on the notion that they’ve built the most frictionless duo in the modern NBA—that perhaps there is still something to be said for the longevity of an NBA marriage, rather than the sheer power of a single season or two together.

The question now is whether all of that time invested will pay off—whether an abiding partnership can still pay dividends in an NBA now defined by player movement, by stars flitting from one city to another until something clicks into place.

“Because I know CJ as a person,” Lillard said, “I want to see him do well. I want to see him receive accolades. And he wants the same for me, because he knows I want it for him. I think just really being friends—that matters.”

Michael Weinreb is a freelance writer and the author of four books.