Tied to the 20th anniversary of Bring It On, we hereby dub the next five days Teen Movie Week. Dig up your varsity jacket, pull up to your cafeteria table, and re-live your adolescence as we celebrate the best coming-of-age movies ever made.

The state of the cheerocracy was not always so strong.

Twenty years ago, Bring It On opened to middling reviews and just respectable late-summer box office numbers, the latest in a seemingly endless string of low-to-mid-budget, PG-13 high school comedies. (A year later, the parody Not Another Teen Movie sighed glibly at the trend.) Bring It On seemed easily dismissible as factory-made fluff, no different than the usual foray into lunchroom caste systems, humiliation comedy, and a little light romance. But months later, Bring It On was a DVD phenomenon. A few years later, it was spun off into the same direct-to-video cottage industry that was built around American Pie, which had been a much bigger hit for Universal the year before. (The one difference: Bring It On’s five sequels did not have a Eugene Levy quietly cashing checks.) Now it seems like only a matter of time until cults collide and the 2011 musical version of Bring It On: The Musical, with music and lyrics cowritten by Lin-Manuel Miranda, gets a Broadway revival.

So what changed? It’s probably as simple as audiences assuming the worst of a teen comedy released in the dog days of August and slowly figuring out they were wrong. Bring It On wasn’t a radical break from end-of-the-century high school comedies, but it was simply better than them in every respect: bright, stylish, impeccably cast, and extremely funny, with the right mix of earnestness and irreverence in its approach to the world of competitive cheerleading. Working from an original script by Jessica Bendinger, first-time director Peyton Reed wrings all the laughs he can out of this combination of gymnastics, dance, and demented pageantry, but respects it as a sport of high stakes and true athleticism. The film also pivots on themes of cultural appropriation that not only seem unexpected in a cheerleader comedy, but remain pressing and pertinent 20 years later. Conversations about choreography fit right alongside conversations about white privilege.

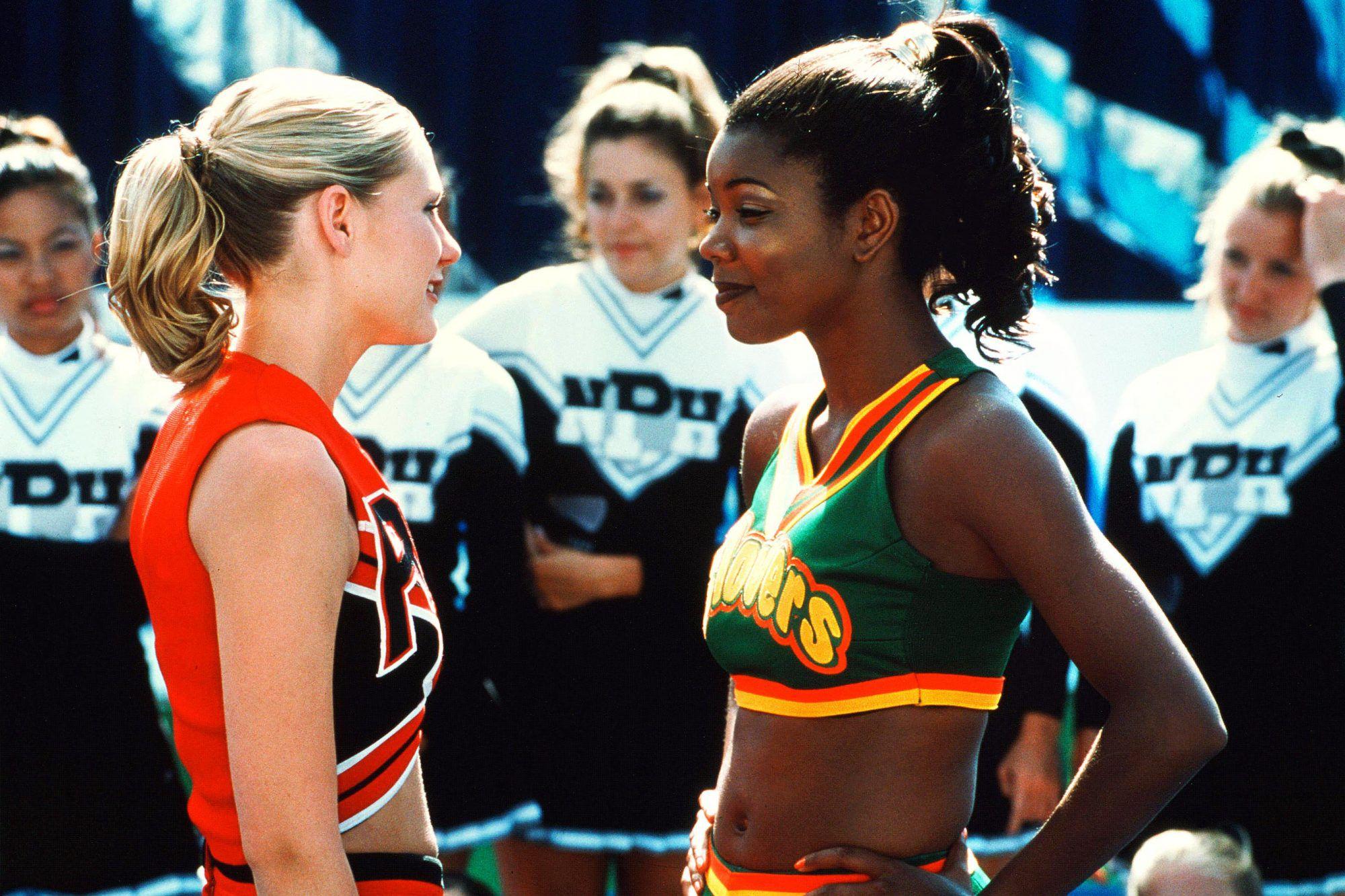

Reed also lucked into casting Kirsten Dunst as Torrance Shipman, the new squad leader for the Toros of Rancho Carne High School, along with several other great actors in secondary spots: Importing much of the punk irreverence she brought to Faith on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Eliza Dushku contrasts perfectly with the squeaky-clean Torrance as Missy Pantone, a transfer student who helps the Toros chase their sixth straight national title; Jesse Bradford had starred in Steven Soderbergh’s Depression-era drama King of the Hill as a child, and he’s charmingly low-key as Missy’s brother and Torrance’s love interest; and Gabrielle Union is a revelation as Isis, leader of the Clovers of East Compton High School, whose routines have been lifted by the Toros for years.

Bring It On has proved far stickier than anyone would have imagined 20 years ago. As a sport, cheerleading itself has grown out of a subculture and into the mainstream, and when the Netflix’s Cheer and USA Network’s cheerleader noir Dare Me premiered within a couple of weeks of each other last winter, there were traces of Bring It On in both of them—the intense friendships, the intrasquad rivalries, the massively elevated stakes of a seemingly frivolous pursuit. For his part, Reed parlayed the success of Bring It On into the retro style of 2003’s Down With Love, and then the hit comedies The Break-Up and Yes Man; more recently he’s claimed a piece of the Marvel Cinematic Universe as the director of Ant-Man and Ant-Man and the Wasp. In quarantine, putting the final touches on a second-season episode of The Mandalorian, he took time to reflect on the making of Bring It On, the current state of studio comedies, and why Sparky Polastri is a prime candidate for a spinoff series.

You came to Bring It On with a pretty long résumé of directing music videos and TV comedies, but this was your first feature film. How were you able to make the leap to doing it?

I was in New York doing the first three episodes of Season 2 of UCB and before I left, I got this script from my agent. He said, “Listen, I’m going to send you a script. It is a high school comedy, and I know you’re into high school comedies.” And I was like, “Oh, what’s it called?” He said, “It’s Cheer Fever.” And I said, “Well, what is Cheer Fever?” He said, “It’s actually ... well, it’s a competitive cheerleading comedy.”

[Sighs.] “OK, yeah. Send it.” I admittedly was thinking it was something I would read a few pages of and would not be into it. But I read it, and in the first couple of pages, Jessica Bendinger’s script had that opening cheer, which was almost verbatim to what ended up being in the movie. And I thought it was really smart from the beginning, because it grabbed you, and it confronted the audience’s preconceived notions about cheerleaders right up front, and it was really funny, and also felt like, “Wow, this is really visual. This could be like a mini Busby Berkeley musical number to open the movie.”

So I got really excited on those first couple of pages and kept reading, and then found the specificity of her writing really exciting. It had its own sort of vernacular, but it really examined this subculture that I knew nothing about and it made a case for competitive cheerleading as a sport, with these really memorable characters.

Then you got further into the script, and it’s like, “Oh, holy shit, they’re dealing with themes of cultural appropriation and race and gender and all this stuff.” It had some serious themes going on underneath the frothy trappings of a cheerleader movie. It felt like a whole different way into a high school movie.

What were some of the teen movies that were most pertinent when you were thinking about approaches to this story?

It was really a wide range. American Graffiti meant a lot to me growing up. Later, Say Anything… was a big one. I loved that. I like stuff in some of the John Hughes movies—this was a different tone, but it wanted to sort of incorporate some of those things. But I think the commonality of the ones that I like is how they create specific and interesting characters and deal with the politics and the status system of high school. Jessica’s original draft was almost like the Godfather saga. She was examining the relationship between cheerleaders and the dance squad. There was stuff we ended up having to cut out of the script, because it was just too unwieldy. But she had created this whole ecosystem in her draft and clearly had done the research.

Jessica Bendinger’s original draft of Bring It On was almost like the Godfather saga.Peyton Reed

Bring It On, to me, was about positivity more than anything. I wanted it to be a very hopeful movie. The cultural appropriation thing was really interesting to me, because your protagonist, Kirsten’s character Torrance, is a product of white privilege. The Toros are this well-moneyed, five-time-national-championship-winning cheerleading squad, and she learns that it’s all built on theft. Her first instinct is like, “Let’s hire somebody and maybe cheat our way back into it.” Then she decides that she has to make it right, and ends up making mistakes in that. That subplot was grounded in reality, but it was also very positive.

The theme about white people co-opting Black culture is one of the aspects of Bring It On that makes it unique among teen movies. You said a few times on the director’s commentary that you didn’t want it to be preachy, so how did you approach that?

If you’re making a movie that people expect to be just fun and frothy, and if you’re going to wade into those more serious themes, they can’t feel like they’re coming out of left field. You have to feed them into the thing, and that was one of the biggest challenges of the movie—how to do that in a way that felt real.

I wanted to create characters that did not seem like mouthpieces for a certain point of view. One of the great things about Jessica’s original script is that it Trojan-horses these themes in there. To me, it was just trying to make all the moments as real as possible, in the writing and certainly in the performances; to elicit all the actors’ points of view about it. Gabrielle Union was invaluable in creating the character of Isis. We talked a lot about issues of race and what we did and didn’t want to do between Torrance and Isis.

A scene that stands out is the one where Isis tears up the check. So many films about the relationship between white people and Black people emphasize white charity or white participation in the advancement of Black characters. This seemed like a pretty conscious rejection of that idea.

We never wanted to set out to make something that even remotely approached being a white savior movie, because that’s not what the movie was about. We liked the idea of Kirsten’s character having a genuine desire to make it right and to try and level the playing field. And as a child of privilege, her first instinct is to go to her dad and see if the company will come up with the money and sponsor the other team. In her mind, that’s sort of her privileged white girl reaction like, “Oh, I’m going to solve this thing.”

Isis doesn’t want charity. [The Clovers] want to get there their own way on their own merits and not be beholden to anybody else. That felt real to us. This is a character learning from another character and taking her first step outside of her worldview and realizing that she’s complicit in this sort of institutionalized racism, and that the Toros are direct beneficiaries of cultural theft. And what does that mean? How do you make it right? Finally landing on this idea that they can’t be the best unless they’ve gone up against the best, and the Clovers are the best.

How much research into the world of competitive cheerleading did you do, and what kind of impact did that have on the movie?

Jessica Bendinger was the one who did the lion’s share of the research and put it into the script. But I went down and spent time at these cheerleading competitions and at the cheerleading camps. And San Diego, where we shot the movie, is a huge hub of this cheerleading activity. As we put our actors through this cheerleading camp, I wanted to make sure that we were as accurate as possible, because for me it wasn’t like making a baseball or basketball movie, where I essentially knew the rules of the game. There were all these specifics about how high school cheerleading rules are different than collegiate, all of these things. There are still some mistakes in the movie, but it was all about capturing the spirit of it. I did a lot of research in terms of the scene, the vibe. I really wanted to immerse myself in that subculture—all the positive things about it and the negative things about it—and try and get as broad a view of it as possible.

One detail that made it into the movie is that these big trash cans were set up backstage, anticipating the certainty that some girls would be vomiting before the show.

Oh yeah. It’s weird. Cheerleading competitions combine that fierce competitive spirit of any other sport, but also the glamour of a beauty pageant. And like any of these things, they practice and they practice, they rehearse and they rehearse, and then it all comes down to one key performance. It’s just so fraught with tension. It’s amazing in that way. You can feel that energy.

Was there a casting process for Torrance? Was it always going to be Kirsten Dunst?

It wasn’t always going to be Kirsten. Before my involvement with the movie, [producers] had actually gone out to Kirsten, and Kirsten had passed on the movie. So when I first got back to L.A., one of the first things in prep was to meet with Joseph Middleton, our casting director, who had set up a lunch with me and Marley Shelton. I had lunch with Marley and I thought, “Oh, wow, she could be a really good Torrance.” But I remember Joseph Middleton saying, “OK, you should know Marley is up for another movie, so she might not be available.” And then he says, “And you should also know it’s another cheerleader movie.”

It’s been 20 years, and it feels kind of quaint to me and almost like a minor miracle that we got to make that movie.Peyton Reed

[Laughs.] My first reaction was like, “Holy shit, there’s another cheerleader movie? What the fuck?” And it turned out it was this thing at the time that was called Sugar & Spice & Semi-automatics. It later became Sugar & Spice, about bank-robbing cheerleaders, which is very different than Bring It On. But at the time, you’re just thinking like, “How can there be two cheerleader movies in the marketplace?!”

Marley chose the bank-robbing cheerleader movie, so then my first instinct was to go back to Kirsten. Jessica and I had done more work on the script, and I wanted to be able to send it to her and talk her through what we wanted to do with the movie. At that point, she was in the Czech Republic doing another movie. But Kirsten and I got on the phone and talked about it, and I answered all her questions and stuff, and she ended up signing on to the movie, which was fantastic, because you knew from a very young age that Kirsten was such a talented and soulful actor—like, she really went deep and would be such a great anchor for this movie. So that was a thrill.

We’re also gonna have to talk about Sparky Polastri.

That character was always in Jessica’s script, with “spirit fingers” and all that. And having just come off UCB, I had been just blown away by Ian Roberts’s improv skills, so he was cast. Jessica and I talked a lot about that character, because in the initial drafts, he was just sort of this kitschy kind of cheerleading choreographer who was peddling these bad routines. And Ian brought this great anger to the character. I like the idea of a guy who thinks he’s Bob Fosse, but he’s really this sort of pill-popping crook.

Jessica and I have talked about in the streaming age, like, “Wouldn’t it be amazing to get Ian to come back and play the Sparky Polastri role, but design like a Better Call Saul series, where he’s involved in the seedy underworld as some kind of weird, failed choreographer, with a Rockford Files kind of vibe?” I liked putting Ian’s energy up against these young high school cheerleaders—that always seemed to have comedic potential to me. And again, if you know Ian or know his work, he just throws himself into it. So that was something where he was always there in the script, but when Ian came in, we encouraged Ian to throw as much as he could into that character.

He’s kind of like the monorail salesman in that Simpsons episode, going from town to town, selling the same broken routine.

Yeah. It’s going to be part of the Bring It On Shared Universe. It’s going to go on and just have all these different tendrils in different genres.

Bring It On was a fairly low-budget studio comedy, which just doesn’t really exist anymore. How does a film like Bring It On get made today, and where might it get made?

I don’t think Bring It On would get made at a studio. They don’t have the interest or the ability to make and support movies of that budget. Because they spend so much on prints and advertising and all that, that it doesn’t make it worth it. It’s very rare to see that. It’s been 20 years, and it feels kind of quaint to me and almost like a minor miracle that we got to make that movie. Because I think if that movie were made today, it would be a streaming thing—maybe for the same budgetary range, but it would definitely be a streaming thing.

I don’t want to look back on it through some sort of romantic lens, but I did like the idea that I got the opportunity to do a low-budget movie at a studio. And it felt like at the time, they kind of wanted to nurture young talent. In the studio environment now, that’s increasingly rare. Those opportunities are moving to streaming, because I do know a lot of young filmmakers who have gotten a shot at Netflix or Amazon or something, whether they go from TV to do features, or coming in and doing low-budget features. I also think it’s getting more diverse, which is great.

But wasn’t it Mel Brooks who talked about how a comedy needs an audience? That’s something missing from this equation, at least in terms of a bunch of people gathering in the same space to watch and laugh together.

Selfishly, as a filmmaker, there’s no greater thing than to be in an audience, packed with people, and have them laugh at something in your movie. It’s the best, and you don’t get that in streaming, obviously. I’d like to think, without sounding out of touch, that there’s always going to be a place in pop culture for the communal moviegoing experience and not just giant blockbuster stuff.

But you could see comedies migrating to streaming, even before the pandemic. With studios, unless you have a gigantic name attached to it, it’s harder for them to justify making those movies. So streaming, in some ways, feels like it’s been a savior to comedy. I like to think that there’s going to be some business model that works for the theatrical distribution of medium- and smaller-budget comedies, but it’s a mystery.

Looking back at reviews of Bring It On at the time, I was surprised to discover they were not terribly kind. How’d you take that at the time—and how do you feel about the movie now?

I remember initially, [Roger] Ebert’s was not a glowing review. And then years later, he went back and reassessed it, and ended up calling it “the Citizen Kane of cheerleader movies,” which was always hilarious to me. Jessica and I have talked about this over the years, how particularly male audience members would come up to me and say they liked the movie, but would always sort of qualify it at the beginning by saying, “Hey, I know that movie is not for me.” Or, “Listen, I had no intention of going to see a cheerleader movie. But, hey, man, I really dug it.” There’s always that qualifier at the beginning. But it was always our intention to make something that appealed to guys and girls.

Over the years, the more serious-minded underbelly of the movie has aged well. But also, a lot of the movies I love are just engineered to be repeat-viewing movies. I always like something like Back to the Future, which I can just watch ad nauseum on TV when it comes on. I wanted the movie to have that narrative thrust. Hopefully, it’s kinetic and exciting, and it can withstand the scrutiny of repeat viewing.

I’m guessing you’ve watched the documentary series Cheer?

Yeah. That documentary has this creepy sense of dread constantly. You wonder, “How hard are they going to push these kids?” I think there was a character who had maybe like three or four concussions. And at a certain point, you’re just like, “What are you doing?!” It’s nuts. I was watching that with my wife and seeing these kids who had multiple concussions, and thinking “Well, this is not worth it.” And then I thought, “Oh, holy shit. Am I even remotely responsible for this in some way?”

That’s true. The film is cited quite a bit as a touchstone for a generation of cheerleaders.

Yeah. I don’t know if Sylvester Stallone felt that way about boxing.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Scott Tobias is a freelance film and television writer from Chicago. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, NPR, Vulture, Variety, and other publications.