Has Rotten Tomatoes Ever Truly Mattered?

As recently as a few years ago, the movie-review aggregator was seen as something of an industry bogeyman. But is there a correlation between box office receipts and a high (or low) score on the Tomatometer? We dug deep into the numbers to determine that.On Thursday, Christopher Nolan’s new would-be blockbuster Tenet came out in recently reopened theaters across the United States, following an expectations-surpassing $53 million international launch. Although the late-August debuts of Unhinged and The New Mutants already reinstated the American movie market in forgettable fashion, Nolan’s feature is the first big-budget tentpole to test mid-pandemic demand. Theaters in some states, including California and New York, remain closed after a nearly six-month moratorium on moviegoing, but thanks to Nolan’s name, Tenet represents a real referendum on most Americans’ willingness to brave the multiplex en masse.

The last time a Nolan-directed movie hit theaters, in 2017, Hollywood was facing what in pre-pandemic times struck some unsuspecting studio executives as an existential threat. By the standards of summers when domestic movie theaters were actually open, mid-2017 was a tough time for the movie industry. Despite strong showings from Wonder Woman, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Spider-Man: Homecoming, and Nolan’s Dunkirk, domestic movie revenue reached its lowest point in decades, dragged down by flops like Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets, Baywatch, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, The Mummy, Transformers: The Last Knight, and The Dark Tower.

Those disappointments had something in common: They all received far-from-fresh scores on Rotten Tomatoes, which collects critics’ reviews and presents the percentage of them that the site deems positive or negative. After 2020’s total shutdown, past hand-wringing about box office hazards seems quaint, but three years ago, Hollywood was panicking about Rotten Tomatoes. Between June and early September 2017, Wired, the Los Angeles Times, The Hollywood Reporter, and The New York Times, along with The Ringer, published lengthy reports examining studios’ widespread perception that the review aggregator was tanking attendance.

“The real concern with Rotten Tomatoes was that it became such a go-to place for people and could kill a movie much more quickly than was traditional,” says Bruce Nash, the founder and publisher of movie industry data provider The Numbers. “It used to be that your friends would go on Friday, you would chat to them about the movie before you decided to go on Saturday. But now it’s much more immediate.” Although Rotten Tomatoes had existed since 1998, its traffic and visibility had increased over time, especially after Comcast’s movie ticketing company Fandango acquired Rotten Tomatoes and its parent site, Flixster, in 2016. “Rotten Tomatoes scores were being woven into the ticket-buying behavior in new and different ways,” says Ben Carlson, the SVP and general manager of entertainment research at MarketCast. Because Rotten Tomatoes scores were integrated into the Fandango purchasing process, Carlson continues, “the Rotten Tomatoes number became much more of a pass/fail for people when there were multiple movies that they could make decisions on.”

That put a scare into studios, and one chief executive of a major movie company told the Times’ Brooks Barnes that he was making it his mission to destroy the site. Yet a few days after the Times piece was published, a counter-narrative emerged. Yves Bergquist, the founder and director of the Data & Analytics Project at USC’s Entertainment Technology Center, posted a cursory study on Medium that showed little correlation between 2017 Rotten Tomatoes scores and overall box office returns or opening-weekend earnings. Bergquist’s conclusion that Rotten Tomatoes wasn’t responsible for spoiling box office performance echoed around the internet, popping up in articles via Variety, Entertainment Weekly, The Washington Post, Vulture, The AV Club, Quartz, Gizmodo, Polygon, Engadget, IndieWire, Salon, and several other outlets. Depending on the week and the website, readers could come away with one of two conflicting conclusions: Either Rotten Tomatoes was destroying the industry, or it didn’t matter much at all.

By the end of 2017, box office grosses were down only 2.7 percent year over year, and revenues rebounded to a record high in 2018. The great Rotten Tomatoes terror of 2017 started to seem overblown: Maybe the downturn hadn’t been because the website was big, but because the pictures got small. As Nash says, “Whenever the box office has a downturn, the studio executives are going to go, ‘Well, it’s not us. It’s Rotten Tomatoes. We’re not making movies that nobody wants to watch, it’s that Rotten Tomatoes is telling them not to watch them.’”

The truth likely lies in the middle: Rotten Tomatoes wasn’t tanking the industry or single-handedly exposing that Baywatch was bad, but it wasn’t irrelevant, either. In fact, our analysis reveals that Rotten Tomatoes scores are reliably correlated with box office performance, especially for certain genres. But the aggregator’s influence may have been on the wane before the coronavirus struck, and it may matter less than ever in the present uncertain circumstances.

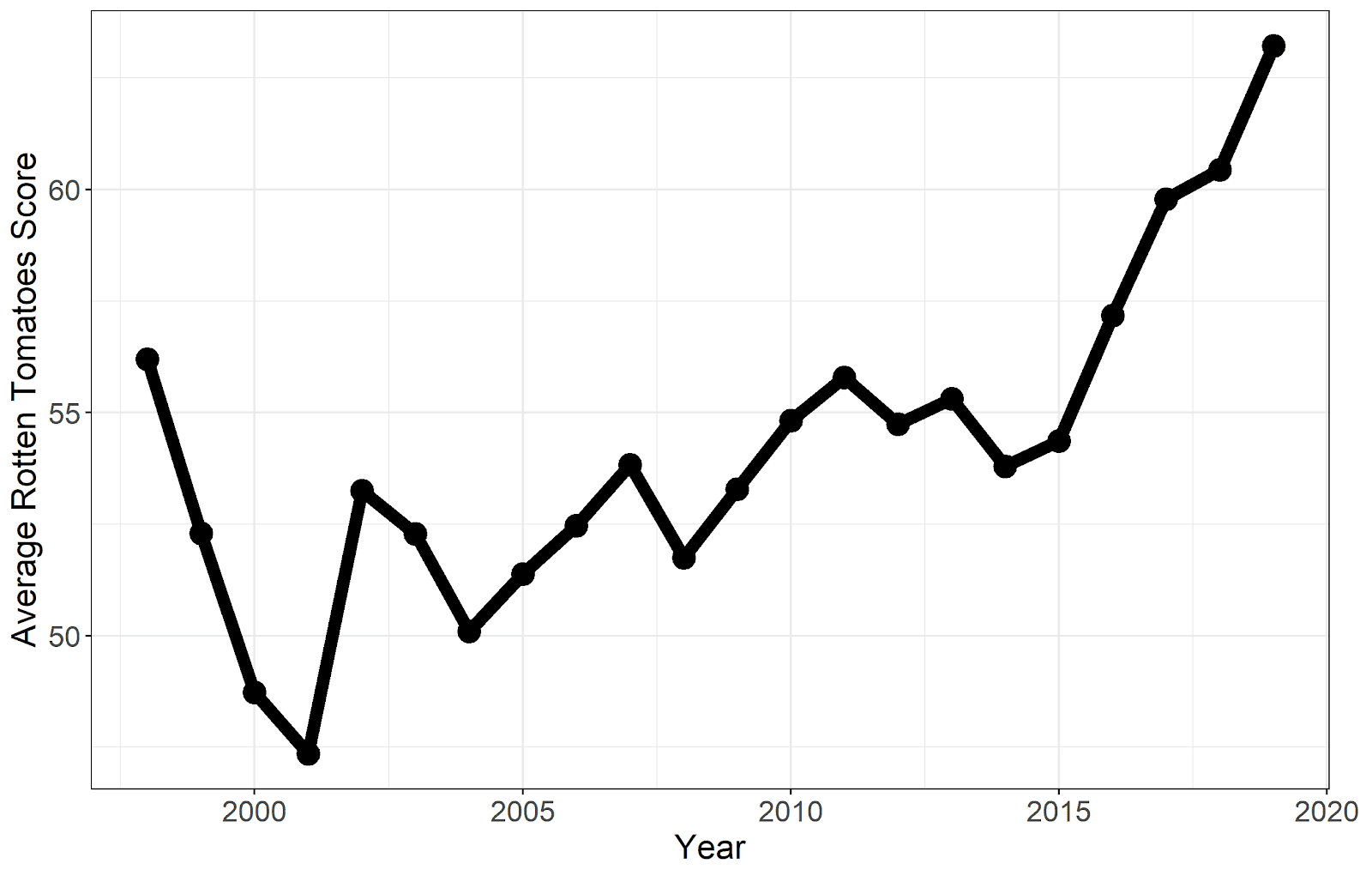

To study the potential link between the box office and Rotten Tomatoes, we gathered budget and box office data for almost 5,000 movies dating back to 1990 and joined it to genre and Rotten Tomatoes score information from the Open Movie Database. Our first finding is that the average Rotten Tomatoes critic score has increased over time.

Maybe movies have improved—or at least grown closer to critics’ liking—or maybe the rise reflects changes in the makeup of Rotten Tomatoes’ pool of reviewers. After a 2018 study discovered that more than three-quarters of reviewers aggregated by Rotten Tomatoes were male and more than 80 percent were white, the site pledged to make its sample more inclusive, partly by approving critics on an individual basis rather than rubber-stamping certain publications, and also by incorporating podcasters and YouTubers in addition to written reviews. Over the next year, the site said, it added more than 600 new critics, the majority of whom were women. Whatever the reason(s) for the increasing scores, there’s no evidence of greater negativity that could be turning off ticket buyers (which probably doesn’t displease Fandango). The site bestows a “Fresh” rating on any movie with a 60 percent score or higher, and the average movie now clears that threshold.

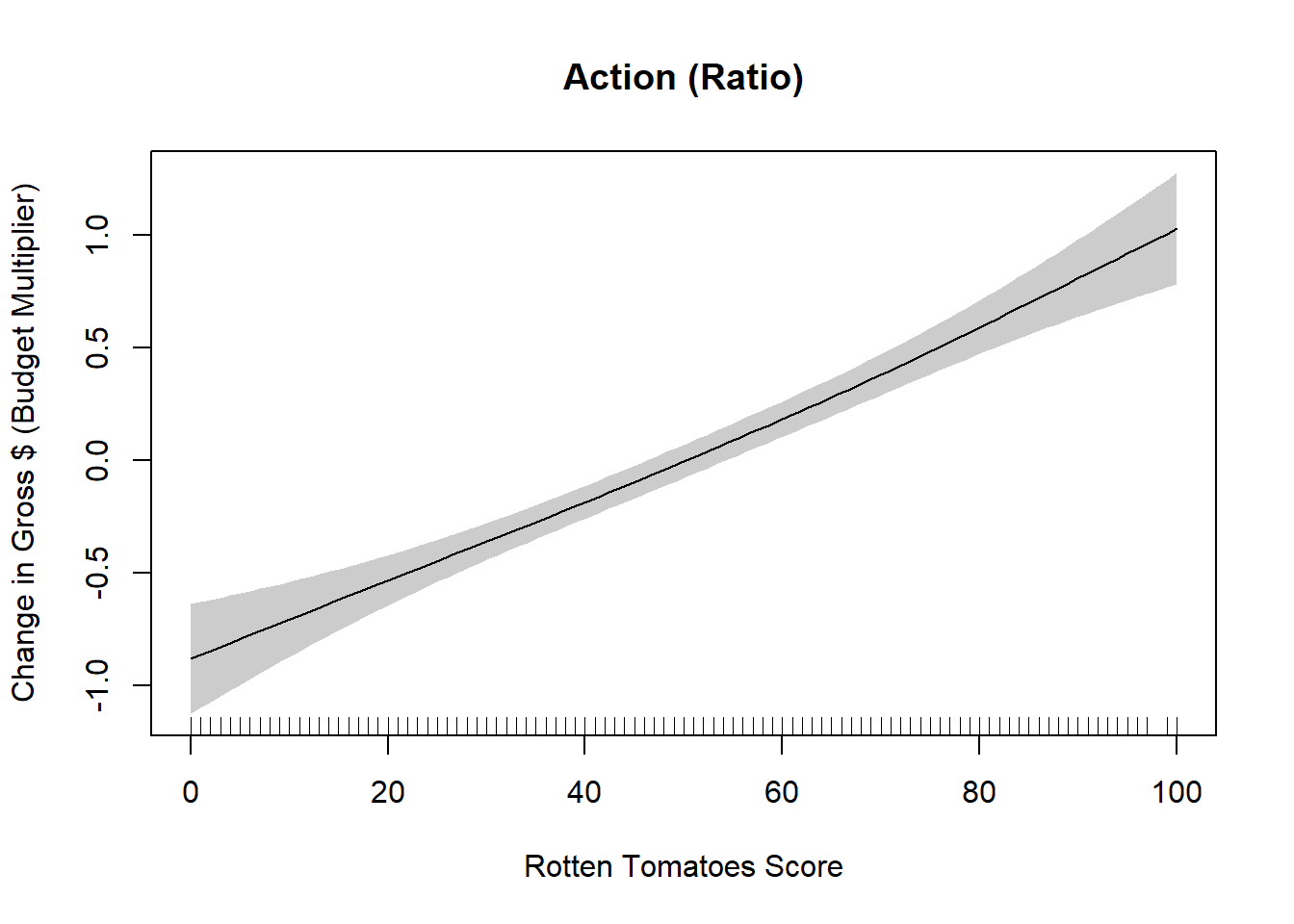

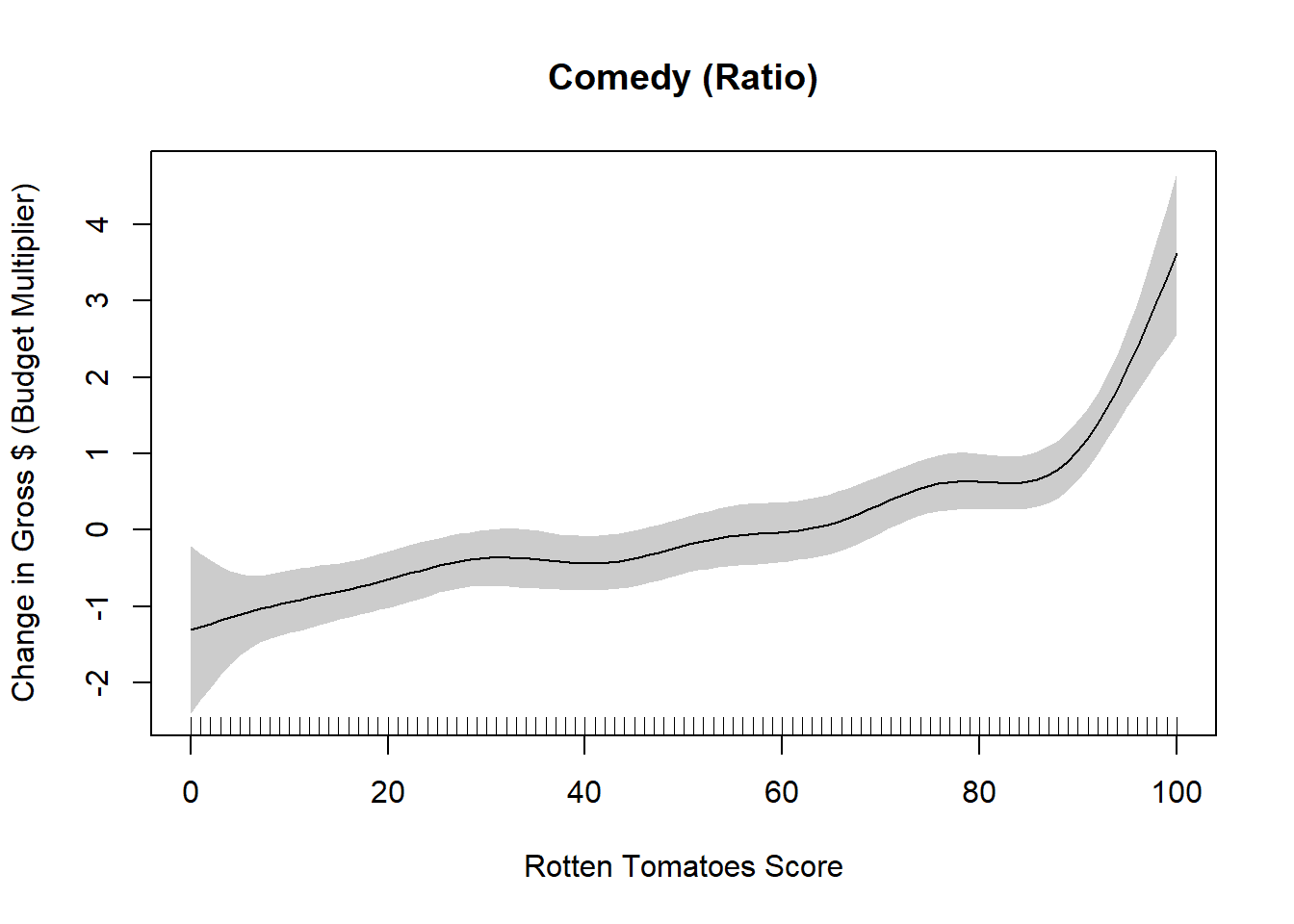

Average Rotten Tomatoes scores vary by budget and genre, and lumping all movies together may obscure meaningful, critic-driven differences in earnings within one genre or within a budgetary range. To account for those confounding factors, we used a generalized additive model, adjusting for budget and genre (broken down into action, comedy, horror, and drama). If a movie was classified as belonging to multiple genres, such as action and comedy, it counted in both buckets. The chart below, which adjusts for budget and genre, shows that on the whole, Rotten Tomatoes scores are associated with higher profit margins (budgets subtracted from box office totals), especially at the extremes.

On average, a movie with a zero percent score (which isn’t unheard of) would be expected to lose about $25 million relative to its budget, while a movie with a 100 percent score would be expected to make about $30 million. That’s a sizable swing, although we can’t attribute the difference entirely to Rotten Tomatoes: A movie with a terrible critic rating might do poorly with or without an online aggregator, based only on negative individual reviews and/or word of mouth.

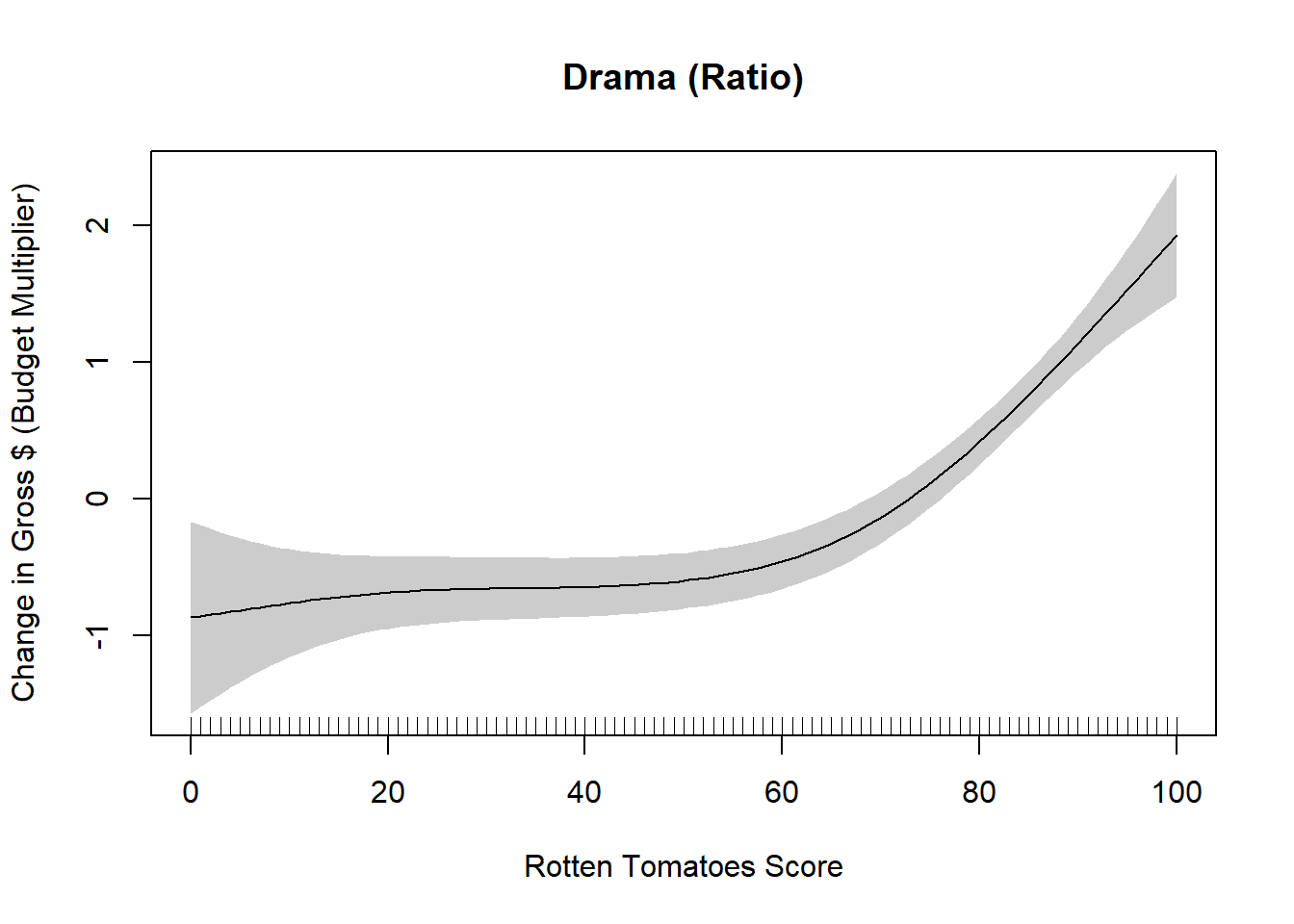

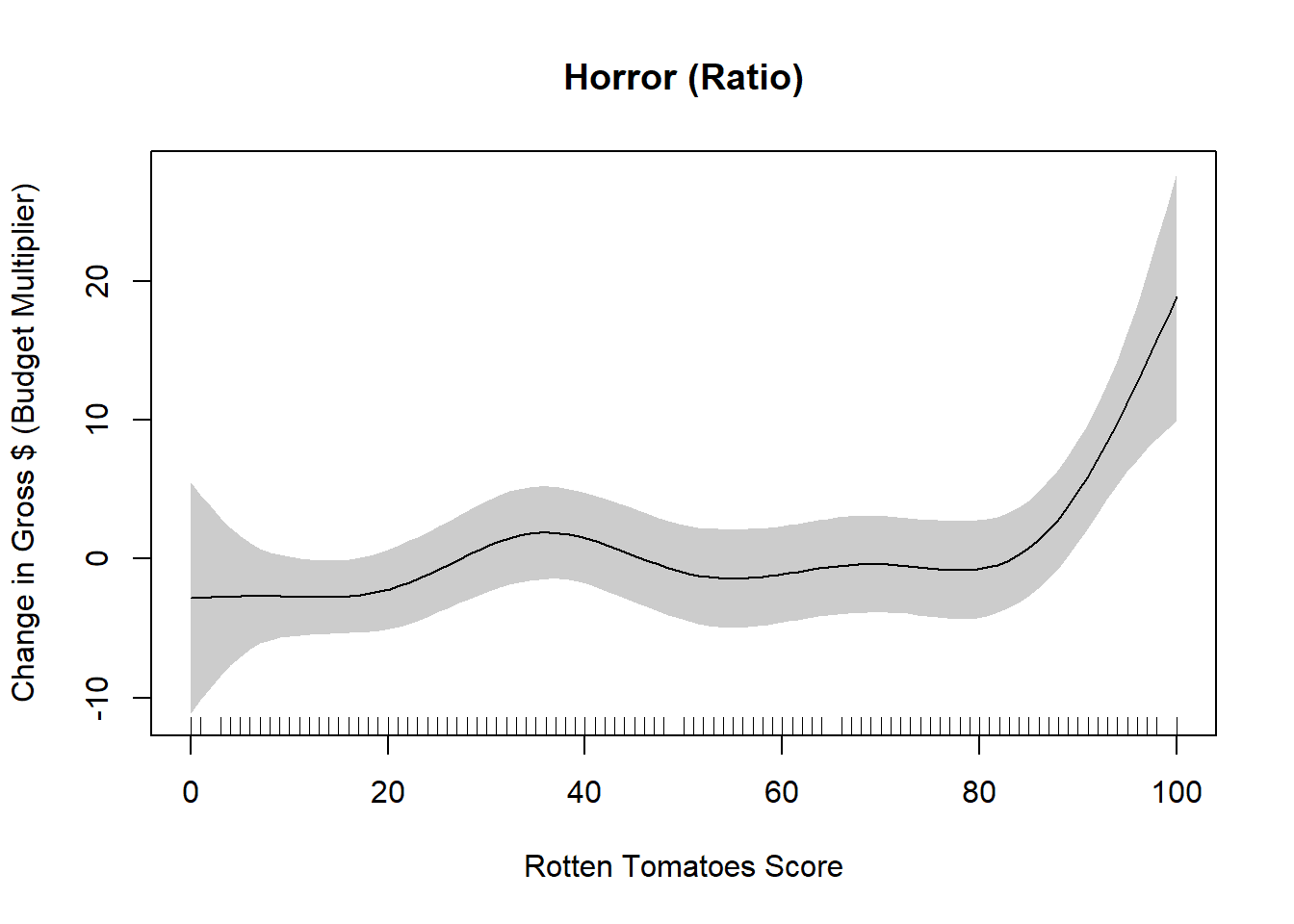

That relationship varies dramatically by genre. The charts below display the ratio of gross box office earnings and budget by genre, from least to most correlated with the critical consensus. Note that the y-axes change from chart to chart, reflecting the differences in scale.

Action movie earnings are the least closely associated with review scores, maybe because when people just want to see stuff blow up, they’re willing to lower their standards in certain respects. Comedies and horror movies—particularly the latter—are far more consistent with the critical consensus. A perfectly scored action movie’s earnings might double its budget, but a perfectly scored comedy can quadruple its budget, while a perfectly scored horror flick can beat its budget by 10 or 20 times, which has bolstered Blumhouse’s bottom line.

Those conclusions align with industry professionals’ findings. “Audience scores matter far more for horror films than any other genre,” says Joshua Lynn, the president of box office forecasting company Piedmont Media Research. The National Research Group’s Ethan Titelman adds, “We definitely see a big impact on the edges. So if a movie is under 20 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, that does usually have a pretty significant impact. And obviously everything over 85, 90 percent, relative to expectations, can have a pretty positive impact.” Titelman cites the theater-friendly Bad Boys for Life, which came out in January and made more than $400 million worldwide (split almost equally between the domestic and international markets) as an example of a movie that may have been boosted by bettering its predecessors on Rotten Tomatoes. Its 77 percent critic score, Titelman says, “wasn’t great, but it was probably a lot better than people expected it to be, and it was the best of the series by a significant margin. That really helped propel Bad Boys for Life to be the no. 1 film of the year so far.” (Not that it’s had much competition.)

The mystery of most interest to studio execs is whether Rotten Tomatoes has strengthened the relationship between the critical consensus and box office performance, which also existed in the pre-internet age. The evidence suggests that the studios were a tad too intimidated in 2017. The three images that alternate in the following GIF show the relationship between Rotten Tomatoes score and overall box office profit margin for movies released pre–Rotten Tomatoes (1990 to 1998), during the first decade of Rotten Tomatoes (1999 to 2009), and in the decade since (post-2010). There’s no clear indication that the two have grown more strongly related.

However, there are some signs that increased attention to the critical consensus may have affected whether movies’ earnings got out to fast or slow starts, even if it didn’t dramatically lower or raise their final ticket tallies. The three images that alternate in the next GIF show the relationship between Rotten Tomatoes score and box office grosses on opening weekends only. This time, we do see a difference in the middle period: The critical consensus began to be linked to openings to a much greater degree. In more recent times, though, that coupling has dissipated slightly.

There are additional indicators that recent developments have sapped some of the power of Rotten Tomatoes. In 2016, the National Research Group started including questions about Rotten Tomatoes in its annual survey of roughly 4,000 moviegoers. That year, 23 percent of moviegoers aged 12 to 74 said they used Rotten Tomatoes to learn more about movies, with the highest usage rate in the 18-to-44 age bracket. In 2017, that number spiked to 35 percent, driven partly by increased reliance among older moviegoers. However, that year appears to have been the peak of Rotten Tomatoes’ penetration. In 2018, the figure fell to 29 percent—not far from the 33 percent of respondents who told Morning Consult in August 2018 that they had checked Rotten Tomatoes before seeing or renting a film (although about a third of that subset said they hadn’t decided against seeing or renting because of the site). In 2019, it dropped to 24 percent.

According to Titelman, “Moviegoers now say they are more influenced by the audience score than the Tomatometer, as they have been losing trust in the opinions of critics, which is especially true among younger and minority audiences.” Jeff Bock, senior box office analyst at entertainment research and data group Exhibitor Relations Co., concurs, saying, “I’m not sure Rotten Tomatoes has the same impact they did a few years ago.” Bock believes that younger viewers are getting their movie recommendations from other sources, such as YouTube and social media, and that some former Rotten Tomatoes visitors have forsaken the site after being burned by disparities between their personal taste and the critics’ collective verdict. “We’ve all watched films based on ‘Fresh’ aggregate scores, and we’ve all likely been upset when they didn’t match our personal tastes,” Bock adds. “You can only do that so many times until you no longer use it as a guide when choosing movies.”

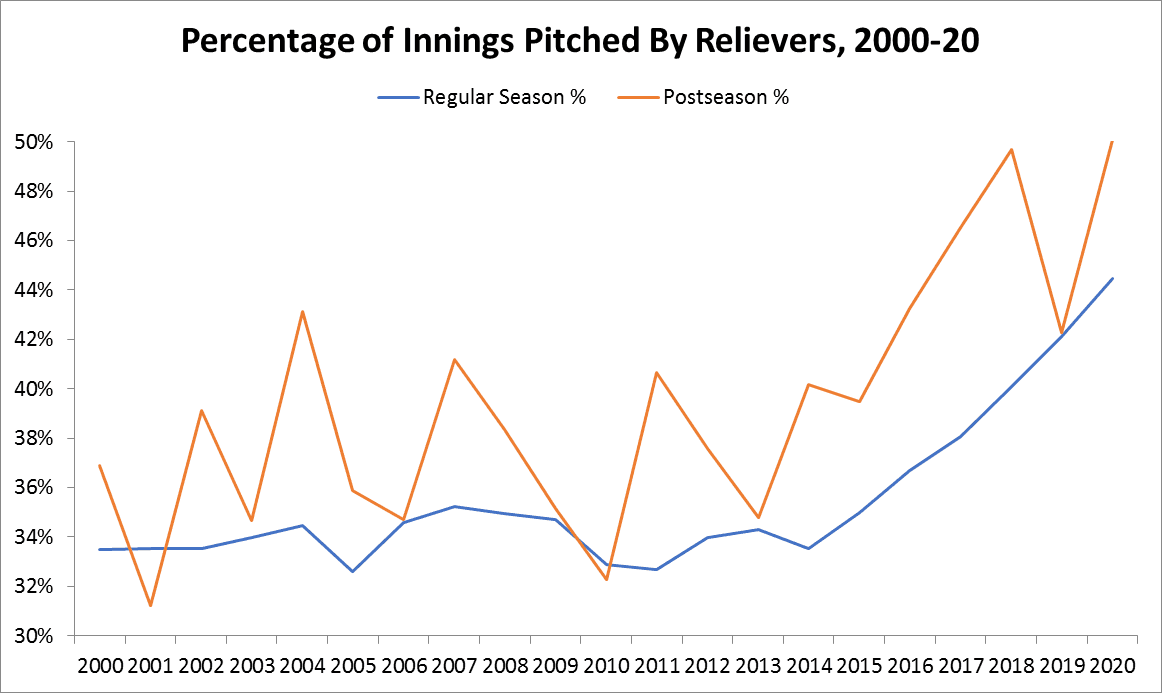

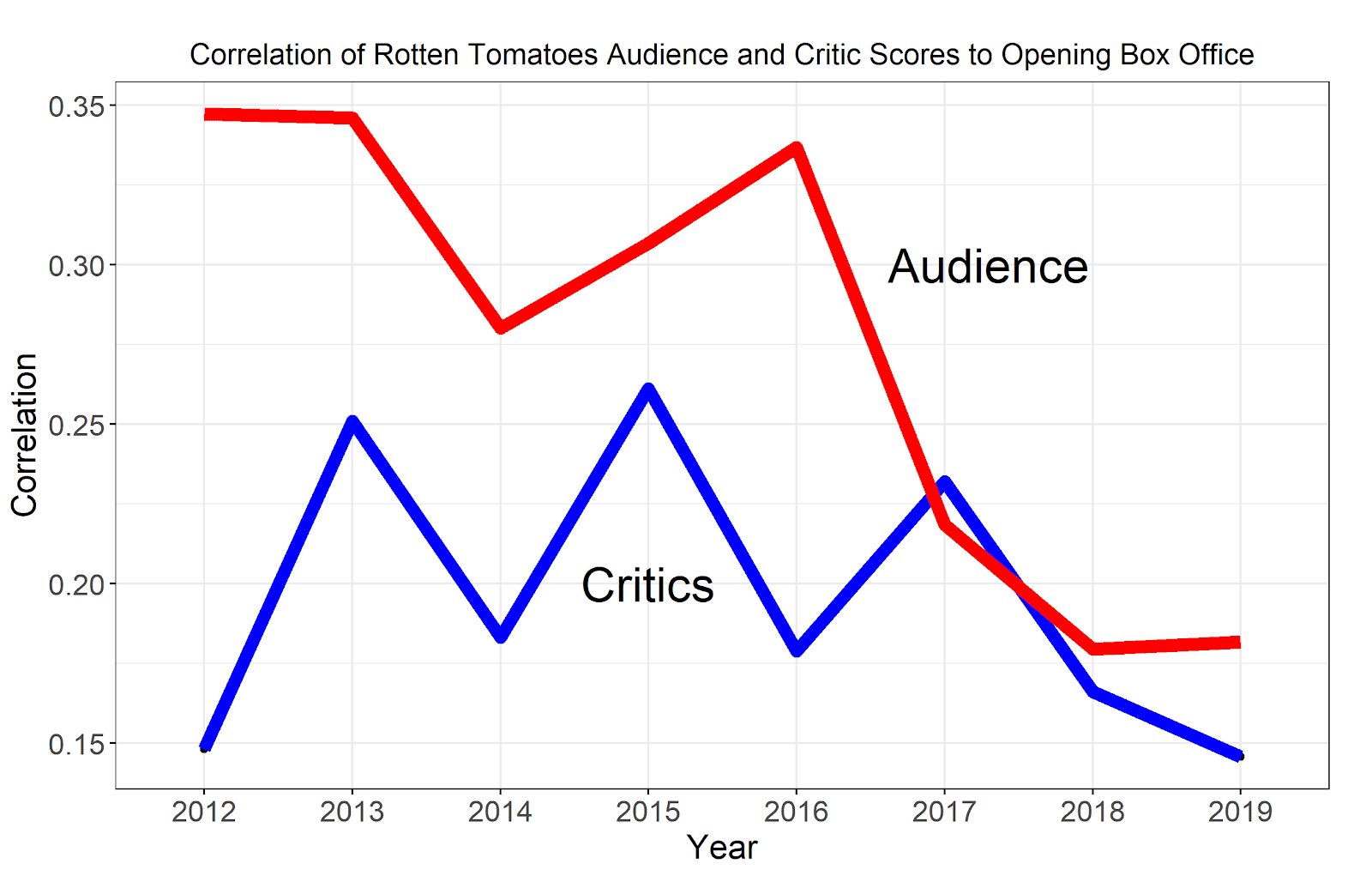

Although our dataset doesn’t include Rotten Tomatoes’ user-submitted audience scores—which have also evolved over time as the site has sought to combat trolls who tried to tank the audience scores for films such as Ghostbusters (2016), Star Wars: The Last Jedi, Black Panther, and Captain Marvel—we did obtain additional data from Lynn. The following chart displays the Piedmont-reported year-by-year correlations between Rotten Tomatoes audience and critic scores and opening weekend box office totals for movies in wide release, which Piedmont defines as those that played at a minimum of 800 theaters.

“While there is a real difference between critic scores and audience scores, with audience scores correlating higher than critic scores, both have a noticeable and statistically significant correlation to opening-weekend box office,” Lynn says, adding that “Rotten Tomatoes scores matter in a tangible way.” Yet the recent trend is obvious: Both correlations have weakened, reaching record lows in 2018 or 2019. According to Piedmont, the judgments of critics and audiences per Rotten Tomatoes have diverged from each other, with the correlation between critic and audience scores declining from .77 from mid-2012 to the end of 2016 to .61 from the beginning of 2017 to March 2020 (a drop of 21 percent). Yet both the relatively lenient audience scores and the stricter critic scores are less tightly tethered to opening revenue than they once were.

Rotten Tomatoes’ adjustments to its audience-score policies and its reviewer-approval process could have helped drive those downturns, but there may have been more at work. Lynn speculates that with major studios releasing fewer films per year than they used to, audiences “might be factoring in that many of the big-budget films are going to be bad” but “still want the spectacle they can only get on the big screen.” Thus, they turned out for Aquaman, The Rise of Skywalker, and Jurassic World even though the reviews were lukewarm to lackluster. Suicide Squad, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, and Justice League (pre–Snyder Cut) each made more than $650 million worldwide despite Rotten Tomatoes critics scores of 40 percent or below.

Along the same lines, Nash notes that Disney, Warner Bros., and other studios have gravitated toward “review-proof” action-oriented event films that attract audience attention based on buzz and marketing. When it comes to sci-fi and superheroes, the critics’ or even fellow spectators’ takes may be inconsequential—except to stans of each franchise—because, Nash says, “You know it’s going to be great special effects and great action, and the sound system is going to be put to full use, and you’re not necessarily there for anything spectacular plot and acting-wise.” Curiously, though, Lynn reports that the correlation between IMDb user ratings and opening-weekend box office has stayed steady even as the Rotten Tomatoes audience score’s connection has plummeted, which could indicate that the widening disconnect (and possible lack of box office clout) in the numbers above is specific to Rotten Tomatoes.

Of course, all of the preceding data was drawn from a world where no one was worried about COVID-19. At present, some portion of potential moviegoers will be basing their buying decisions more on the risk of contracting or spreading disease than on whether they think they’ll like a movie. Conversely, others may be so desperate to return to the theater that they won’t sweat what’s on the screen. “There’s a hope that people are going to be more focused on just the experience of being in the theater and enjoying going to see a movie than they are about how brilliant the movie is,” Nash says. “That’s certainly the case with Tenet. Anecdotally, folks who have gone to see it have been saying as much about how fun it is to be in a movie theater again as whether Tenet is the best movie they’ve ever seen.” (Rotten Tomatoes scores it a 74.)

Nash expects the theatrical-release schedule to be depleted for at least the next two or three months, which will also make forecasting difficult. Instead of, say, one big movie and two smaller movies coming out each week in wide release, many weeks will feature only one, which could be a romantic comedy (like next week’s The Broken Hearts Gallery) or a lower-budget action movie that would typically be relegated to secondary status and have to fight for space in theaters. With less competition, those movies may play on a higher percentage of screens and have long tails to their ticket sales, but the industry’s outlook remains murky. Lynn won’t even offer a guess at Tenet’s take, saying, “There’s just no previous modeling that would make any sense in this environment.” For what it’s worth, Nash expects Tenet to come in at the lower end of the $20-30 million opening weekend range that he’s heard some prognosticators toss out, but he says he can’t be confident. “It comes down to how many people are willing to go to theaters right now, and that is a big unknown.”

Another unknown is whether the theaters that Nolan loves will last. Only 18 percent of people polled by Morning Consult in late August said they were likely to go to the movies in September, and only 23 percent said they were likely to go this year. Some may simply lose the habit. “The industry’s shift to streaming is happening at an accelerated, and likely permanent, rate due to the pandemic, and no one knows what the end result will definitely be,” Lynn says. Disney’s live-action remake of Mulan (81 percent on Rotten Tomatoes), which was scheduled for a wide theatrical release this spring, will instead debut on Disney+ for $30 on Friday and become free for subscribers in December. That film follows in the footsteps of other prominent 2020 releases that were originally intended for theaters but ended up on the small screen, including Trolls World Tour, Greyhound, and Bill & Ted Face the Music. Some streaming services are now talking to studios about producing movies solely designed for streaming platforms, which may ultimately lead to the demise of the cineplex.

Streaming and premium on-demand movies also receive scores on Rotten Tomatoes. But apparently people don’t pay as much attention to review scores when they don’t have to leave their homes. According to Carlson, MarketCast’s social media analytics confirm the findings we’ve discussed: that a higher Rotten Tomatoes score has historically correlated not only to increased conversation on social, but also increased box office, and that the impact has varied depending on genre, size of release, and whether the score was extreme in one way or another. When Rotten Tomatoes panic peaked a few years ago, Carlson’s company (then called Fizziology, prior to its acquisition by MarketCast) helped its studio clients pinpoint the optimal time to lift review embargos to maximize the benefit or mitigate the damage of positive or negative scores.

Right up through this February’s Birds of Prey, Carlson says, Rotten Tomatoes scores still had “a major, major impact” on the conversation surrounding new releases. But “as viewing shifted from the theater to the couch, the impact of the scores on the opinions and social sharing just diminished.” For a typical, pre-pandemic theatrical release, Carlson’s company detected more than 2,000 social media mentions of a film’s Rotten Tomatoes score during its release week. For streaming and premium on-demand movies, that figure falls to 150; far fewer people are citing the scores as reasons to see or not see something. The one exception, he says, is Palm Springs, whose exceptionally high critic score (now 94 percent) was incorporated into the movie’s marketing campaign and helped fuel fan evangelism. “The movies that get the highest amount of conversation around Rotten Tomatoes scores are the films with the most passionate fan bases,” Carlson says. When those scores are positive, “They’re used as justification and a badge of pride. And when they’re bad, it usually opens up a whole bunch of debate and complaints.”

If the future of movies migrates away from the theater, though, those conversations could subside. At home, Carlson says, “the bar is lower in terms of your expectations of quality sometimes, and for what it takes for you to click play from your couch versus getting in your car and driving to the theater.” Thus, the Rotten Tomatoes score is “not part of the conversation in the same way that it was around theatrical.” In other words, Hollywood got what it wanted: Rotten Tomatoes scores may be sliding toward insignificance. But that accomplishment came at the cost of a far greater peril than rotten ratings ever posed.

Rob Arthur is a Chicago-based freelance journalist and data science consultant.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly listed Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom as a movie that performed well despite lackluster reviews. The correct film is Jurassic World.