There’s a scene in the second season of the British sitcom Spaced—the first of a few scenes, actually—in which Simon Pegg’s character, Tim, confesses that he still isn’t over his feelings about The Phantom Menace. “Tim, it’s been over a year,” Tim’s friend and roommate, Daisy, says in the season premiere, which aired in early 2001. “It’s been 18 months, Daisy,” he answers. “And it still hurts.”

The Phantom Menace hurts a lot less now. But for some Star Wars fans, the emotional aftereffects of the first episode of the Skywalker saga have been supplanted by the pain inflicted by the last episode of the Skywalker saga. Disappointing as the prequel trilogy was, at least it went out with a solid last act. Not so for the sequel trilogy. It’s been almost 10 months since the most recent big-screen installment of Star Wars, and The Rise of Skywalker still hurts, too. I don’t want to give in to my anger. I’m trying to keep my concentration here and now where it belongs, as Qui-Gon would want. But people keep picking at my Rise of Skywalker scab.

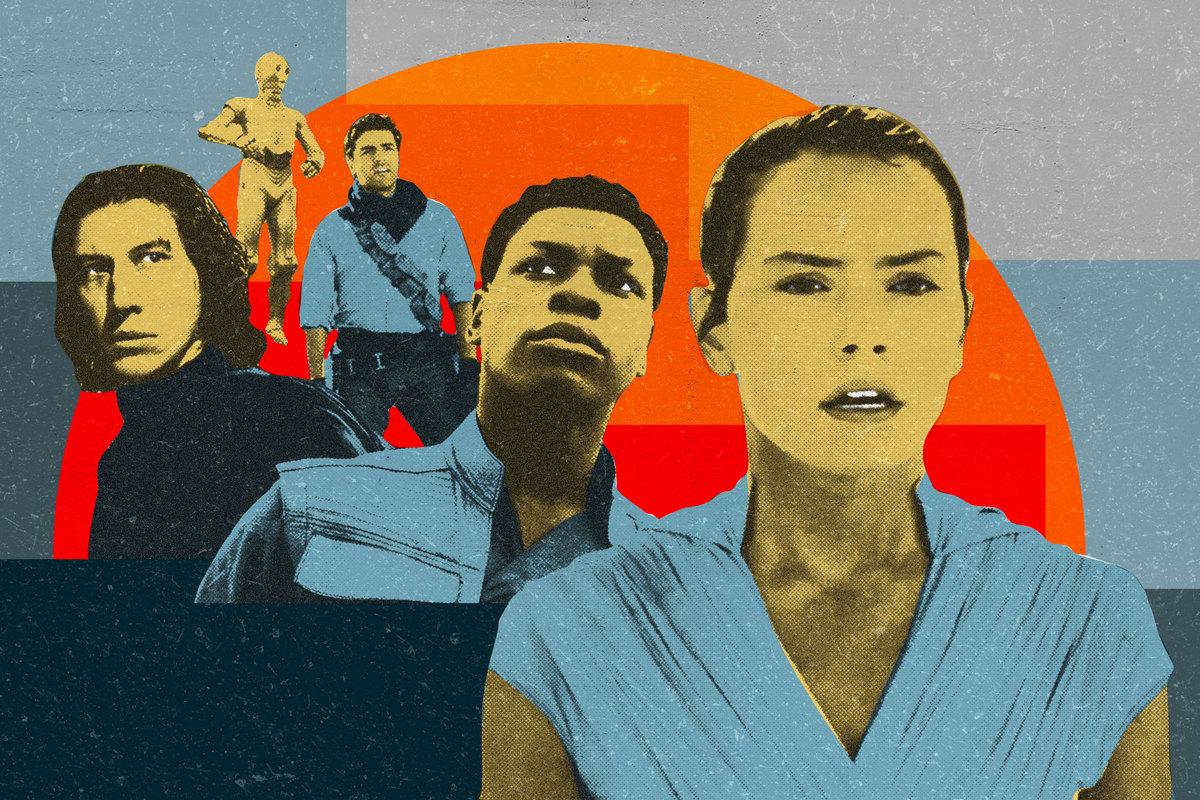

I didn’t like The Rise of Skywalker. I thought it was a derivative, rushed conclusion to the saga that said nothing new, didn’t play well with The Last Jedi, provided no narrative reason for the new trilogy to exist, and, if anything, retroactively sapped some significance from the two trilogies that preceded it. Aside from Solo (which I actually liked), The Rise of Skywalker was the least profitable film of the Disney Star Wars era. It received the worst Rotten Tomatoes score of any Star Wars movie and is clinging to a tenth-of-a-point lead over The Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones in average IMDb user rating. Your mileage may have varied, and hey, I hope it did. I wish I were one of the people who thought it was fine, fun, or fantastic and blissfully sipped soup while the rest of the fan base battled over the conflicting visions of Rian Johnson and J.J. Abrams or pondered what the reaction to the movie meant for The Future Of The Franchise.

More than that, though, I wish I could stop spotting trending topics and reading revelations that make my nerd rage rise anew and leave me dismayed and mystified all over again. Sadly, the discourse surrounding The Rise of Skywalker is harder to destroy than Darth Sidious. Just when one news cycle dies down, a clone controversy appears.

This week, it was Daisy Ridley who fanned the flames of fan outrage, aided and abetted by Jimmy Kimmel Live! guest host Josh Gad. Gad, who hounded Ridley for spoilers during the production of the trilogy, asked her to spill some post-production tea, questioning whether she knew about Rey’s parentage while she was shooting the movies. Ridley denied that she did and proceeded to twist a vibroblade into the gut of every fan who’s contended that the sequel trilogy was poorly planned or envisioned an alternate origin story for Rey.

“At the beginning there was toying with an Obi-Wan connection,” Ridley said. “There were different versions, and then it really went to that she was no one. Then it came to Episode IX, and J.J. pitched me the film and was like, ‘Oh yeah, Palpatine’s granddaughter.’ I was like, ‘Awesome!’ Then two weeks later he was like, ‘Oh, we’re not sure.’ So it kept changing. Even as we were filming I wasn’t sure what the answer was going to be.”

Lucasfilm didn’t have to have everything worked out from the start: It’s not as if the original trilogy was ruined because George Lucas didn’t decide until Empire that Luke and Leia were siblings and Darth Vader was their dad. Then again, if you know in advance that you’re going to get to make an entire trilogy, that you have to finish it in four years, that it’s going to be made by three different directors (which was the original plan), and that the hopes, dreams, and dollars of millions of fans are depending on your decisions, one would think you’d try to ensure that everyone was at least in the vicinity of the same page.

In December 2015, Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy said, “We haven’t mapped out every single detail yet,” which we later learned was a slight understatement. While it was fine not to know what to do with the Knights of Ren or how Rey got her hands on the Skywalkers’ lightsaber, whether Rey was herself a Skywalker, a Kenobi, a Palpatine, or a Jedi Jane Doe seems like the kind of detail that probably shouldn’t have been buried in a secret Sith wayfinder. It continues to be baffling that the people in charge of a franchise as high stakes as Star Wars wouldn’t have worked that out long before beginning the final film, let alone getting to the middle of making the final film. As The Force Awakens coeditor Mary Jo Markey said this spring, “the last part of the trilogy needed one vision.” If we want to be charitable, we could speculate that Abrams was actually committed to the Palpatine plan throughout filming and was keeping his star in suspense to prevent leaks or to elicit a certain performance from Ridley. But depending on when he finally let her in on the truth, not knowing could have impaired her performance.

The week before Ridley reignited the Rise of Skywalker angst, her costar John Boyega—who in April tweeted, perhaps prematurely, that “everyone has moved on” from the film—vented his own justified frustrations about Finn’s arc in the trilogy, telling GQ, “You get yourself involved in projects and you’re not necessarily going to like everything. [But] what I would say to Disney is do not bring out a Black character, market them to be much more important in the franchise than they are, and then have them pushed to the side. It’s not good.” Boyega continued, “You guys knew what to do with Daisy Ridley, you knew what to do with Adam Driver. You knew what to do with these other people, but when it came to Kelly Marie Tran, when it came to John Boyega, you know fuck all.”

In light of Ridley’s revelations, it’s not clear that Lucasfilm knew what it was doing with anyone. But Boyega is right: Finn, one of the most engaging characters from The Force Awakens, was pushed to the periphery over the course of the trilogy, reduced from a lightsaber-wielding reformed Stormtrooper who took on Kylo Ren to an ancillary supporter of Rey’s who only hints that he’s Force-sensitive and doesn’t end up with any of his four possible love interests. Boyega seems to hold Disney and/or Johnson primarily responsible for Finn’s fate and for the perceived sidelining of actors of color, defending Abrams by saying, “Everybody needs to leave my boy alone. He wasn’t even supposed to come back and try to save your shit.” It’s true that Finn first floundered in The Last Jedi—a film that both Boyega and Ridley have disparaged before—but Johnson’s middle movie also introduced Tran’s Rose, only for The Rise of Skywalker to dramatically downsize her role.

The week before Boyega’s broadside, New Mutants director Josh Boone blasted The Rise of Skywalker’s fleeting same-sex kiss as “the most embarrassing” example of queer representation. (Maybe the director of The New Mutants wasn’t the best person to talk about a Disney movie being embarrassing, but he had a point.) Those recent resurgences in Rise of Skywalker buzz represent just a sampling of the flare-ups since last December. Before Boone—well, pick your poison dart.

There was the much-celebrated fan edit that added visible Force ghosts to Rey’s showdown with Darth Sidious. There was the masterful finale of The Clone Wars, which reminded the world what a well-crafted ending to a Star Wars series looks like. There was the release of the Rise of Skywalker novelization, which walked back some elements of the movie, exposed how much was missing from it, and spurred discussions of scenes that might have helped redeem the direction Abrams chose. There were frank comments by Rise of Skywalker writer Chris Terrio and editor Maryann Brandon about how hurried and haphazard the production was. There was the publication of Colin Trevorrow’s original script for Episode IX, which in many respects seemed superior to The Rise of Skywalker’s. And there were the still-unsubstantiated rumors of an “Abrams cut” that conveniently would have addressed some of the most common criticisms of the Disney cut’s detractors (not to be confused with the much more ridiculous rumors of a Lucas cut or a plot device that would decanonize the entire trilogy).

Some of those rumors and reports stack on top of each other in particularly torturous ways. In January, Rise of Skywalker sound editor Matthew Wood divulged that Driver recorded new dialogue for his helmeted character in his closet about a month before the movie premiered, because Kylo’s lines had changed. Is it possible that Abrams brought back the helmet that The Last Jedi destroyed to allow for last-minute dubbing? And given Ridley’s recent comments, could it be that Driver didn’t know what the final script would say about Rey when he filmed the scene in which Kylo tells her she’s a Palpatine? Might that be why he was wearing his helmet, depriving us of the nuance that could have come from his facial expressions? Probably not, but thanks to the never-ending Rise of Skywalker rumor mill, these are the questions that pass through my mind when I could be thinking about anything other than this uninspired, 10-month-old movie.

The most aggravating aspect of Rise of Skywalker’s post-release life is the insidious (no Palpatine pun intended) way in which each vision of the movie that wasn’t made deepens and prolongs fans’ regrets about the one that was. While I still ride for Rey’s “nobody” backstory from The Last Jedi, Rey Kenobi would have made for a better much twist than the ineffectual one we got—if a development that mirrored the original trilogy’s can be termed a twist at all. In that case, a Kenobi could have saved a Skywalker from the dark side, which would have made The Rise of Skywalker a poignant counterbalance to Revenge of the Sith. (Frankly, it’s also a lot less distressing to consider Obi-Wan and Duchess Satine firing protein torpedoes—which they definitely did—than to contemplate Palpatine bull’s-eying somebody’s womp rat, which he probably didn’t.) And if Trevorrow’s Duel of the Fates had happened as planned, Finn would have had a fulfilling farewell as the revolutionary leader of a squad of fellow former Stormtroopers that he’d recruited and commanded.

Like an orphaned Ezra glimpsing his lost parents through the Force in the Rebels series finale, we can picture these happy possibilities, but we can’t touch them. Maybe we’d be better off not seeing them at all. To paraphrase emo Anakin, I’m haunted by the plot points that they should never have given me.

Whoever is most responsible for the trilogy’s lack of direction (or really, its multitude of directions)—Abrams, Johnson, Kennedy, a concealed Sith lord plotting the franchise’s downfall—the mess they made can’t be cleaned up by reading leaked scripts or fantasizing about some Snyder-style intervention. As Han Solo said, it’s all true. Voicing complaints and demanding satisfaction is how modern franchise fandom works, and the fact that some of us stew so long about Star Wars is a testament to the hold it has on our consciousness. But as long as we let The Rise of Skywalker’s failures fester, we’ll stay stuck in the pre-acceptance stages of grief, marinating in an inescapable Sarlacc pit of anger, bargaining, and depression. We all know where anger leads. It’s a bad place to be.

The Rise of Skywalker’s cast members are entitled to get whatever they want off their chests, especially if (as in Boyega’s case) they’re trying to bring light to larger issues. But if fans could collectively declare a moratorium on rehashing, relitigating, and dunking on The Rise of Skywalker, that would be wizard. Just for a few years—however long it takes until the sting wears off, the franchise moves on, and nostalgia sets in, making it possible to pretend that the trilogy was less of a mess or focus on the finale’s few redeeming qualities. Let’s look forward to Star Wars: Squadrons, the second season of The Mandalorian, and a Taika Waititi movie. And let’s let at least part of the past die. The Rise of Skywalker didn’t do that, but Star Wars fans still can.