David Fincher’s Lost Projects

The acclaimed director has an unimpeachable body of work, but why isn’t it more extensive? The answer lies in the long list of movies and TV shows that he hasn’t made.To celebrate the 25th anniversary of Se7en and the 10th anniversary of The Social Network, The Ringer hereby dubs September 21-25 David Fincher Week. Join us all throughout the week as we celebrate and examine the man, the myth, and his impeccable body of work.

For a longtime screenwriter, the email seemed too good to be true. “How would you like to work on this TV show,” Rich Wilkes recalls it saying, “and have no one tell you what you have to do?”

The note was from David Fincher.

The two had almost collaborated in the early 2000s, when Wilkes wrote the adaptation of the Mötley Crüe biography The Dirt. Fincher planned to direct the debaucherous movie. But it didn’t happen. “It got blown apart somehow,” Wilkes says. “Which was really frustrating.”

A decade later, Wilkes was surprised to hear from Fincher. “I don’t know if you know who this is, I’m the guy who wrote The Dirt. I think maybe you contacted the wrong person,” Wilkes remembers responding. “And he said, ‘No, no, I know who you are. Do you want to work on this show?’”

The series was a half-hour HBO comedy set in the world of ’80s music videos, where Fincher’s career had taken off after he directed clips like Madonna’s “Express Yourself” and Paula Abdul’s “Straight Up.” Videosyncrasy centered on a new-to-showbiz production assistant and told the story of the rise of a wildly popular new medium. The first season began with the making of Berlin’s “The Metro” and was set to culminate with the filming of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

Initially referred to by its two working titles, Living on Video and Video Synchronicity, the show had a cast that included Charlie Rowe, Sam Page, Kerry Condon, Corbin Bernsen, and Paz Vega.

For the man behind Se7en, Fight Club, and Zodiac, the tone and format of the series was a departure. But the subject matter was not. “The beauty of working on that with him was, one, he had the inside knowledge of how things worked,” Wilkes says. “But he [also] had the relationships to be able to call up David Geffen and say, ‘Hey, can we use this song?’ Once you get one person to say yes, the next people are like, ‘OK. I’d like to be involved with that too.’”

In early 2015, Fincher and his crew shot a handful of episodes of Videosyncrasy. That June, however, HBO stopped production on the series.

“When we both saw the third and fourth [episodes], we realized we needed to go back and do some work on the scripts,” the network’s president of programming at the time, Michael Lombardo, told The Hollywood Reporter. “David’s attention at that point—he is someone who likes to be hands on, on everything—got diverted by another project.”

That other project happened to be a second HBO show: Utopia, a remake of a British drama that Fincher was producing in collaboration with Gone Girl author Gillian Flynn. But like Videosyncrasy, that series was also in dire straits by the summer of 2015. Rooney Mara had been cast as the series lead; production on a pilot was supposed to begin. But all of that came to a screeching halt when HBO reportedly balked at Fincher’s request to bump up a budget that was already approaching $100 million.

In the end, neither Utopia nor Videosyncrasy saw the light of day. The former ended up moving to Amazon with Flynn as the showrunner; the latter can’t even be found on IMDb.

Perhaps more than any other mainstream director, David Fincher has a reputation for being uncompromising. He’s notoriously meticulous, demanding, and altogether stubborn when it comes to getting the vision in his mind onto the screen. The graveyard of unfinished—or even unstarted—projects left in his wake could be a testament to his single-minded, perhaps even inflexible, nature. But his lost productions are less an indictment of his exacting methods than they are an indictment of Hollywood’s lack of trust in even its most creative filmmakers.

“When a guy like David Fincher gets frustrated to the point that these projects implode,” Wilkes says, “you know there’s something wrong with the business.”

Over the last 30 years, Fincher has directed 11 movies and executive produced three television shows. But that total is dwarfed by the sheer number of things that he was supposed to make. When writer Oliver Lyttelton put together an A-to-Z guide to Fincher’s unmade films and TV series for The Playlist, the compilation ran nearly 4,400 words. And that was in 2014. Since then, the list has grown even longer.

Uniquely, Fincher’s legend has been burnished more by what he hasn’t made than what he has. In an industry where franchise-hoarding conglomerates dish out gobs of money in exchange for ultimate control, he’s refused to cede any ground. And if he can’t do it his way, it seems, then he won’t do it at all.

“It took Spielberg what, 12 years, to put together his Abraham Lincoln biopic? And he’s Spielberg,” says Wilkes, who also wrote the 1994 comedy Airheads and the 2002 Vin Diesel vehicle xXx. “And here’s Fincher, who’s been doing TV shows, but how many years has it been since Gone Girl? It’s not from lack of trying.”

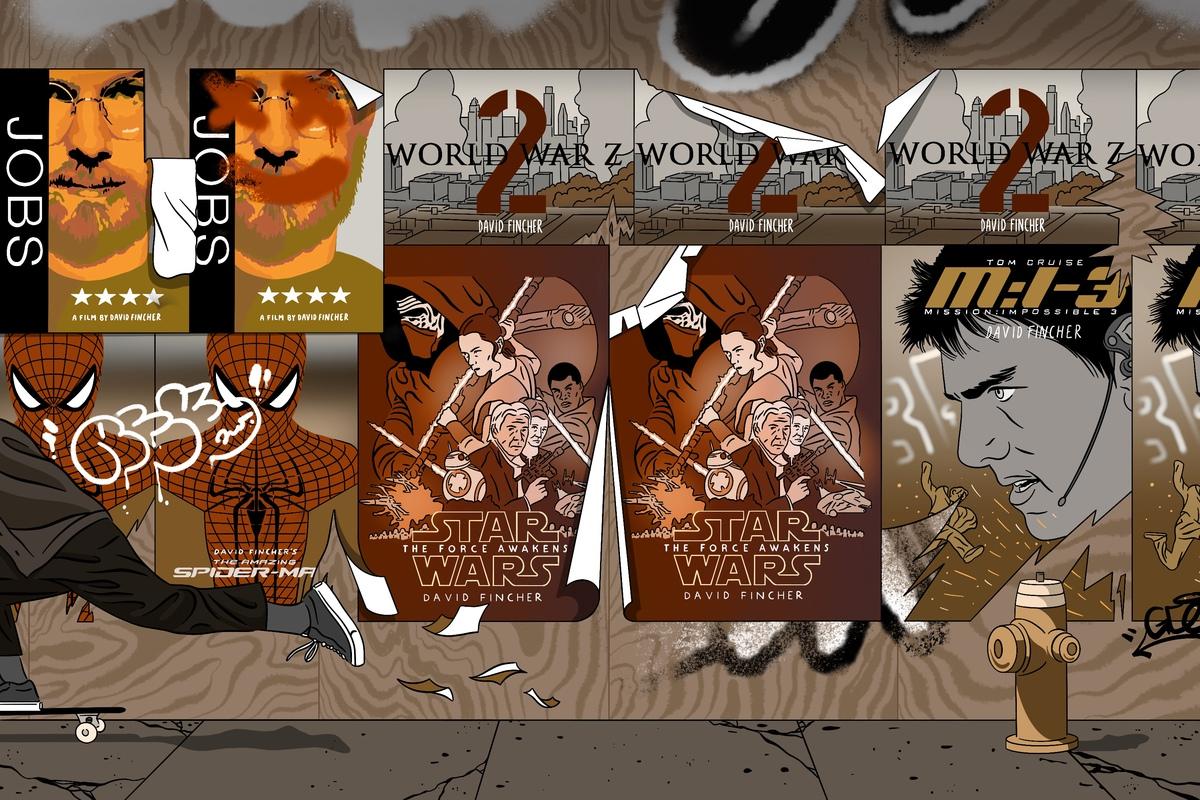

It’s a testament to the coolness of Fincher’s oeuvre that every project he’s been attached to—and then detached from—causes cinephiles to fantasize about what his version of it would’ve looked like. His pile of almosts is as varied as it is tall. Among other genres, he’s been in talks to make summer tentpoles (Spider-Man), biopics (Jobs), neo-noirs (The Black Dahlia), science-fiction epics (Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous With Rama), and animated movies (Heavy Metal). The eclectic collection of Fincher’s unmade films and shows brings to mind a principle often attributed to critic Roger Ebert: “It’s not what a movie is about, it’s how it is about it.”

When a guy like David Fincher gets frustrated to the point that these projects implode, you know there’s something wrong with the business.Rich Wilkes

Take, for example, Videosyncrasy. “It was a half-hour show in the vein of something like Entourage or Veep,” Wilkes says. “A completely different tone for David. And that’s what made it really, really interesting.”

When it comes to picking source material, the director has never been afraid to leave his comfort zone, if he has one at all. In 2008, A. Lee Martinez published The Automatic Detective, a sci-fi/noir novel about a 700-pound robot cab driver named Mack Megaton who sets out to solve an unsettling mystery. The author didn’t view it as easily adaptable for the screen: “I love the book but it is one that I would’ve been amazed if anybody did anything with,” he says.

But sure enough, one day 12 years ago, Martinez’s agent told him that Fincher, Blur Studio, and the company’s founder Tim Miller hoped to turn the book into an animated film. The inquiry startled the writer, who recalls noting that “they don’t mind taking ambitious chances.” They even gave Martinez some concept drawings of things like mutants in ’50s-style suits. “The art they sent me was really good,” he says. “It captured the retro noir/science-fiction flavor. I was surprised. It was better than I would’ve imagined.”

Alas, Fincher and Blur’s option on The Automatic Detective eventually ran out. It still hasn’t been made into a movie.

While it’s not uncommon for high-profile creative types to pick up and then unceremoniously drop cool-sounding projects, Fincher is what Lyttelton called a “serial attaché,” a director who’s constantly lining up new films but ultimately makes fewer than planned. When a serial attaché shows interest in an author’s work, it’s exciting for the writer. But it can also be agonizing. “It’s almost like the kiss of death,” says Lyttelton, who’s recently moved from journalism to screenwriting. “[Your script] could sit on a desk for like, three years.”

Still, Fincher isn’t just discerning for the hell of it. Because 20th Century Fox meddled so much during the making of his feature-length debut Alien 3, he’s tended to only stick with ideas that he can painstakingly shape without interference.

“He puts a strong differentiation between the creative and the financial,” Wilkes says. “One of the things that he told me about one of his projects that had blown up was that the studio said, ‘We need to talk about the movie before we start shooting it.’ David said, ‘All right, you have a choice. You can either talk to me about the script, or you can talk to me about the budget. But you can’t talk to me about both. Because if you have creative notes on the script, fine. We’ll deal with those. But you can’t nitpick on both ends. And if you want to talk budget, then fine. We’ll figure out a way to bring it down.’” But when it came to the actual content of the project, Wilkes recalls Fincher emphatically asserting, “We’re doing whatever the hell we want.”

His irreverence toward the bean counters has probably prevented him from helming surefire blockbusters. In 2002, Variety reported that Paramount hired him to direct Mission: Impossible 3. “You can never make exactly the movie you want to make,” he said back then. “But if [the studio] let us do even half of what we want, it should make for a pretty interesting film.” Within a few years, Paramount had replaced him, first with Joe Carnahan and then with J.J. Abrams. In a 2008 interview with MTV, Fincher coyly addressed what happened: “I think the problem with third movies is the people who are financing them are experts on how they should be made and what they should be. At that point, when you own a franchise like that, you want to get rid of any extraneous opinions. I’m not the kind of person who says, ‘Let’s see the last two, I see what you’re going for.’ You’ll never hear me say, ‘Whatever is easiest for you.’”

In the early 2010s, Fincher met with Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy about potentially directing what became Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Once again, he didn’t seem interested in allowing a studio to dictate the direction of one of his movies. (And once again, a studio went with Abrams.)

“It’s tricky,” he told Total Film in 2014. “My favorite is The Empire Strikes Back. If I said, ‘I want to do something more like that,’ then I’m sure the people paying for it would be like, ‘No! You can’t do that! We want it like the other one with all the creatures!’”

It wasn’t the first time Fincher took issue with a Disney-controlled property. Beginning around 2010, he was developing a wild adaptation of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea that was reportedly going to star Fincher’s former collaborator Brad Pitt. But when the director couldn’t cast it the way he wanted to, he passed.

“It became very hard to appease the anxieties of Disney’s corporate culture with the list of names that allowed everyone to sleep at night,” Fincher told Little White Lies in 2014 while promoting Gone Girl. “I just wanted to make sure I had the skill sets I could turn the movie over to. Not worrying about whether they’re big in Japan.”

As caustic as Fincher can be, the reluctance of studios to give him the creative freedom that he desires defies logic—most of his movies have been profitable and critically acclaimed. Then again, this should surprise no one. After all, Warner Bros. only agreed to finance Inception, the fourth-highest grossing film of 2010, when Christopher Nolan agreed to do The Dark Knight Rises. In show business, the surest thing is prized more than the most exciting thing. On that same press tour six years ago, Fincher told Playboy that “a lot of people flourish at Hollywood studios because they’re fear-based. I have a hard time relating to that, because I feel our biggest responsibility is to give the audience something they haven’t seen.”

On that last point, Fincher has kept his word. Since Alien 3, he hasn’t directed an installment of any other existing film franchise.

Yet long after Fincher has proven himself to be an unyielding filmmaker, studios are still trying to entice him to take charge of their most potentially lucrative movies. Just last year, he was set to direct the World War Z sequel before—surprise!—a budget squabble caused Paramount to pull the plug.

Despite spending the last three decades fighting against big-budget homogeneity, Fincher will seemingly always remain a sought-after tentpole director. In a way, it’s ironic. Because each of his films is so distinct, he’s often seen as someone who’s creative and stylish enough to invigorate an existing franchise. But what Hollywood often fails to embrace are the very things that make him great: the instinct, the unbending nature, the determination to stick to a vision. So while his body of work holds up remarkably well, we’re left with far fewer Fincher projects than there could, and should, be.

“It’s just endless how frustrating it is,” Wilkes says. The screenwriter knows from experience. In addition to Videosyncrasy, he planned to collaborate with Fincher on several more projects. One was based on a novel that they couldn’t secure the rights to. Another was a doomed biopic. “The people that owned the life rights suddenly decided, on the verge of us actually shooting, that they wanted some creative input into how the movie was gonna be made,” Wilkes says. “And David, he likes to have it entirely his way. He’s been screwed over too many times in the past.”

Wilkes’s Mötley Crüe script, however, did eventually get made into a movie. Fincher, of course, didn’t direct it—but you can imagine what it would’ve been like if he had.