Jed Tai’s long-distance bills got out of hand in the mid-’90s. The calls were going out to remote locales like Three Rivers College in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, or Dixie College in St. George, Utah. Letters were written to schools like Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, under the guise of a Paladins basketball die-hard who dated his fandom back to the days of Clyde Mayes, a power forward selected by the Milwaukee Bucks in the 1975 NBA draft. Whatever it took to sound reputable enough that a school might share their numbers with him. Of course, Tai had no connection to any of these institutions, but they had what he wanted: Latrell Sprewell’s point total in junior college; Keon Clark’s block count the one season he played JuCo ball in the middle of the Mojave Desert; a Xeroxed copy of the entire 15-year catalog of team statistics kept by the Furman sports information director.

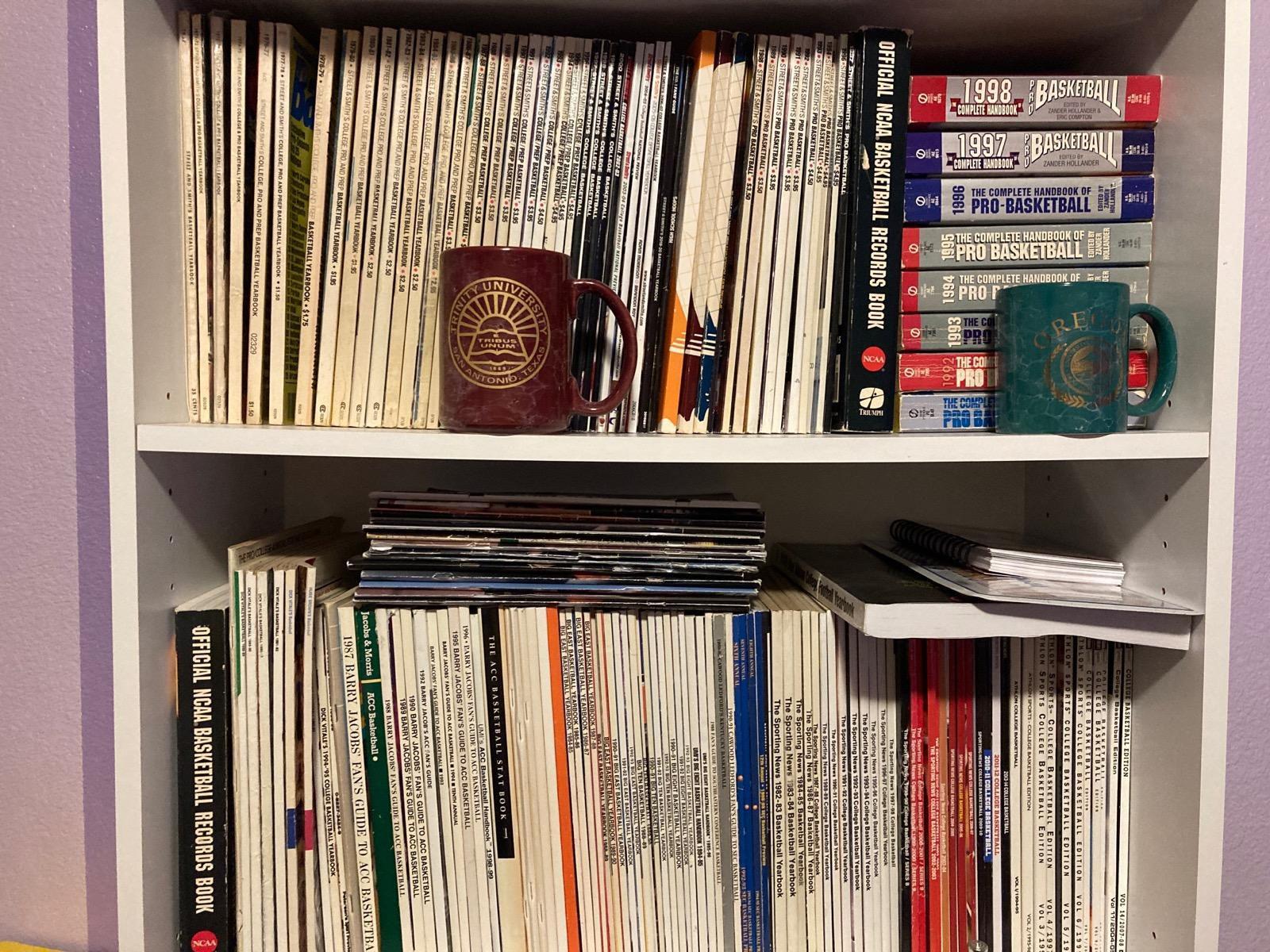

Tai, then a senior engineering student at the University of Illinois, was in pursuit of every basketball program in the nation that produced an even remotely relevant NBA prospect. He could find most of the statistics from the hoard of USA Today issues and annual guides like Street & Smith and the Blue Ribbon College Basketball Yearbook (created by future NBA general manager Chris Wallace) that he’d amassed over the years. To fill in the gaps, he contacted the schools directly, and either had sports information directors recite numbers over the phone, or send sheets of statistics through mail. He input the data he collected into his own personal Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheets, wherein he would devise formulas that would calculate a player’s value based on their stats—a sort of proto-PER. It was a mindset he’d cultivated in childhood, playing Strat-o-Matic Basketball as a kid and developing a love for the hidden morsels of meaning embedded in statistics.

“I grew up in Kentucky, and being Asian American, there weren’t a lot of people like me, so I often felt very alone, socially awkward,” he told me. “Basketball kind of became my outlet—I was just the numbers guy and was really interested in stats and measured how basketball players performed. I can remember facts like that really easily. My mom would say, ‘How come you didn’t use that to become a doctor or something?’”

Tai had been gathering basketball stats, both pro and amateur, his entire life through books and all the media of communication available to him. But it wasn’t until around his sophomore year of college, when he was granted access to Usenet—a spiritual antecedent to Reddit and Twitter that predates the World Wide Web—and assumed the moniker of Jazzy J that his stockpile of numbers found a new raison d’être.

On November 18, the 2020 NBA draft green room will take on a different form than usual. (Well, it’s still not green, and it’s still not a room, but—) Rather than being the usual designated arena staging area full of banquet tables just before the commissioner’s podium, the green room will exist inside a designated server operated by ESPN, funneling in dozens of live smartphone video feeds from the living rooms of superlative NBA prospects around the world.

The draft is an explosive mingling of intelligence and intuition, potential and projection—it only makes sense that both its art and science would grow alongside the Age of Information. Most draftniks today will have a familiarity with each prospect’s face, physique, comportment, and athletic capability. They will have already internalized all the relevant heuristics: the player’s strengths, weaknesses, statistical profile as compared with the rest of the draft field, and the tier in which the player ranks. They will have opinions on the player’s shooting mechanics, touch around the rim, and awareness (or lack thereof) as a team defender. They will have access to publicly available in-game footage for every player drafted, dating back at least two years on YouTube. For some, like LaMelo Ball, the footage will date back much farther than that; if you dig deep enough, you’ll find a 12-year-old Ball, with a Michael Strahan smile, cutting a short promo for himself. It can all be summoned instantly.

It wasn’t always this way. Thirty years ago, there was no video on demand, but there were a ton of manually inputted Unix commands. (The next time you find yourself complaining about the latest Twitter redesign, take a breath and look at what online communication looked like back then.) Usenet ruled the day as the preeminent social network, a discussion platform that linked connected servers and allowed point-to-point communication through email for Unix users (initially, between Duke and the University of North Carolina), before a wider network of participating servers was created. Throughout the ’80s, email addresses had been reserved for researchers, computer engineers, and other members of academia, but an explosion of access followed in the early ’90s with the newly minted World Wide Web made available to the public. Usenet’s technical roots mutated in that time, and its architecture became an ideal hub for people to explore and nurture their other common interests. But it wasn’t always the quick-and-painless process we see email as today. Messages were not transmitted instantaneously to everyone; they had to follow the correct paths to the destination. Someone on the West Coast looking to send email to a researcher at UNC would have to know how to access the AT&T server, which was connected to NC State’s, which was connected to UNC’s. The process of sending messages back in the early days of Usenet meant having an acute understanding of how the digital sausage got made, because you were your own butcher. Still, it beat the alternative of not being connected with kindred minds.

“The Net shrinks the world by making global information local,” Ellie Cutler presciently wrote in a 1993 story about online basketball discourse for Global Network Navigator, the very first commercial web publication. “For instance, my source of Phoenix Suns news is no longer restricted to AP wire stories in The Boston Globe, but is expanded to include coverage from columnists, coaches, players, and fans in Phoenix. In return, I can post a scouting report on Boston College forward Bill Curley for the UseNet NBA Mock Draft, or details of Larry Bird’s latest back operation for a Celtics-starved fan in Finland.”

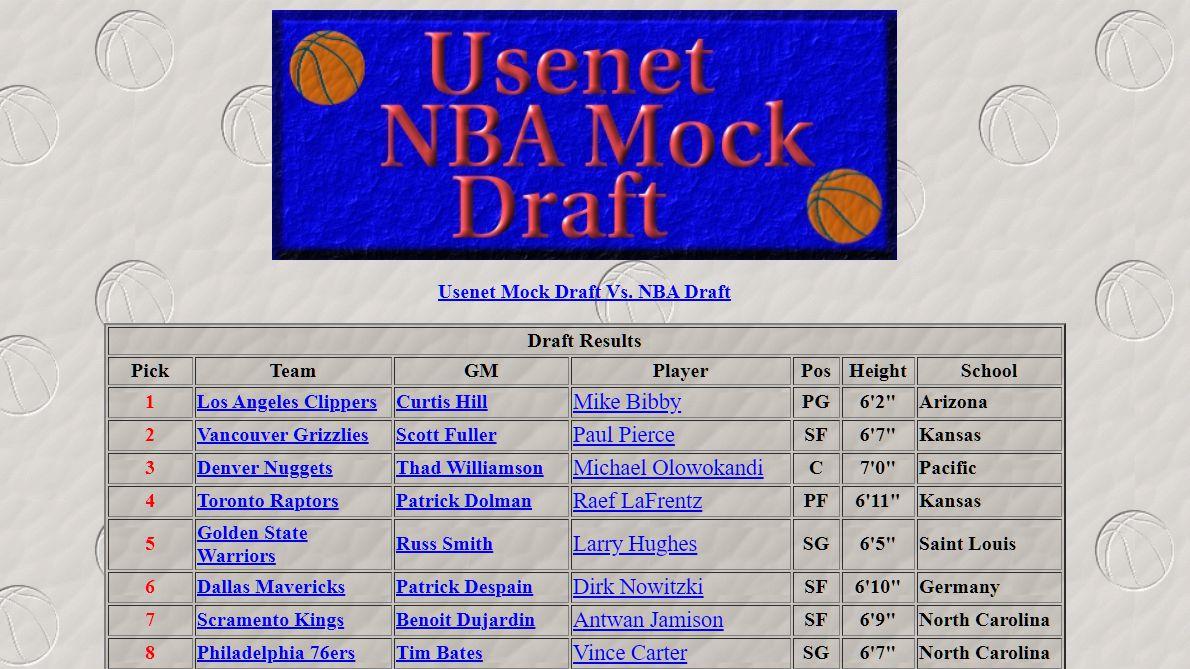

The Usenet Mock Draft is precisely where the internet’s NBA draft industrial complex all began. With the help of Google’s newsgroup archives, we can trace the roots back to a Usenet post sent on May 20, 1991, the same year the World Wide Web was made publicly available. It was an open call for participants in a team-by-team mock draft, sent out the morning after the Charlotte Hornets won the draft lottery. Matthew Merzbacher, then a UCLA grad student working on his PhD, was the Usenet Mock Draft’s first commissioner, offering his fellow nerds the opportunity to play scout or GM.

The 1991 Usenet Mock Draft was the first mock draft published on the internet, but it, too, followed a lineage. The mock draft had been popularized in the ’80s through pioneering NFL draft writers like Mel Kiper Jr. and Joel Buchsbaum, and national publications like The National soon thereafter adopted the format amid its growing popularity. Usenet, however, offered something novel: a globalized scouting department consisting of ball-obsessed engineering students and computer science researchers with eyes on the ground, watching local NCAA games not broadcast on ESPN. “Mock drafts existed,” Merzbacher said. “We just crowdsourced it.”

What would become an annual feature (from 1991 to 2004) of rec.sports.basketball.pro (rsbp), one of the early internet’s most popular fan communities, wasn’t meant to be an enterprising endeavor. The mock draft was originally conceived as a petty provocation. Usenet’s network of newsgroups, or specific channels of discussion, are broken up into topical hierarchies, which then break into more specific streams. For all of the 1980s, rec.sport.basketball was an all-encompassing newsgroup for college, NBA, and international basketball discussions. But by the early ’90s, a motion had been passed to split the group into four distinct channels: college, pro, international, and miscellaneous.

Merzbacher was opposed to the split. “I’m a troublemaker. One of the arguments I made was ‘Hey, well, what if you have a mock draft?’ Was it college, or was it pro? Should you have the college expertise of where the players are coming from, or the pro expertise of where they’re going? So that’s actually why I started it,” he said. “And of course it was a complete failure, as far as getting it to stay as one group. But it made the point.” (The Mock would become a fixture of the pro channel.)

A year later, the keys to the Usenet draft were handed over to Craig Simpson, a University of North Carolina graduate who was one of the principal scouts in the first edition. Under Simpson’s 12-year stewardship, the mock draft became something of an institution, consistently shining a light on the collaborative potential of a globalized web. It was there that Tai’s collection of statistics found a home—nearly every prospect profile from 1994 on carried full year-by-year statistics courtesy of Jazzy J. Rob Clough, an avid rsbp user and onetime Usenet draft commissioner summed up the project thusly: “This particular grouping of fans really represented a nice coalition—people who had particular college fandoms, people who had particular NBA fandoms—and merging that knowledge for something that, at its best, was as good and as predictive as any of the newspaper reports or magazine articles we would see about it.”

Kobe Bryant was already a star by 1996, but his national profile took a bit of time to catch up. The buzz of his potential leap from high school directly to the NBA was baffling at the time; his performance at the McDonald’s All American Game in late March—the only real look most casual fans were able to catch of Bryant’s talent—was unremarkable. He looked like a boy unfit for a league of men, without the advantage of supreme size that allowed Kevin Garnett to make a stunning prep-to-pro transition one year earlier. Simpson sent the first round of callouts for 1996 Usenet draft scouting reports back in April, more than two months before the draft; it wasn’t until the fourth callout in May that Kobe even showed up as a prospect to be written about.

A random scouting report landed in Simpson’s inbox weeks later. It painted as clear a profile of Kobe as one could expect on the early web, with descriptors we now know to be foundational to his legacy as a player: intelligence, determination, idolatry at the altar of Jordan. It was penned by someone who’d played local high school and summer games against the future legend. “That was not common,” Simpson said.

Where NBA fans today can peruse Synergy and other databases for footage and statistics fairly easily, being a Usenet scout meant reporting on what you saw—whether it was a live game at a rival school, or extracting what little information could be gleaned from a draft-centric Peter Vecsey column in the New York Post or USA Today. “It took a lot of effort to scour things to get basketball info, because the modern age of the NBA being a 365-day-a-year sport was not even close,” Clough said. Some scouting reports were woefully incomplete; some were unnecessarily grandiose. The nature of the open-call format left a lot of room for variance.

Over the years, I’ve returned to the Usenet draft scouting reports, whose oldest entries resemble long-winded Notepad files, time and time again. It’s grounding to know that NBA fandom, for all the talk of a generational schism, hasn’t changed all that much. The wheels of online sports discourse have long been greased by the particular schadenfreude of exposing a bad sports take with the benefit of hindsight. NBADraft.net’s legendarily overwrought DeShawn Stevenson–Michael Jordan comparison in 2000 remains one of the great digital artifacts of the 21st century, but people on the internet were passing delusion off as expert eyes years before. One of my personal favorites from the Usenet Mock Draft archives? A 1995 scouting report of Brent Barry:

My favorite player of all time is Magic so you have to believe me when I say that Barry is the second best passer in modern day basketball.

What caught my attention is more the audacity of the statement, not the sentiment. It’s not hard to see where the enthusiasm for Barry came from: The Oregon State senior was an explosive, sharpshooting 6-foot-6 wing with the length, height, and creativity to make passes that most guards wouldn’t have the ability to attempt. I have the benefit (or detriment) of two and a half decades of hindsight to state with certainty that history does not view Brent Barry as one of the greatest passers of all time, but he didn’t lack the skills to be—just ask Kevin Garnett, Rasheed Wallace, or Michael Finley about the 1996 Rookie Challenge.

Occasionally, the scouting reports saw vague mirages of the future. In 1993, Vin Baker was a lanky 6-foot-11 perimeter player out of small-school Hartford whom NBA scouts deemed a small forward at the next level. He had size, length, range out to the 3-point line, and the ball skills to lead a break. Many questioned the durability of his frame, then housing only 215 pounds. “Seems like the only disappointing thing about Baker is that he won’t play center in the NBA,” wrote prominent rsbp user Ellie Cutler, who served as a longtime scout and Boston Celtics GM. Her mode of thinking was not so far removed from that of Ringer writer Jonathan Tjarks, who over the years has written about players with the potential to exploit market inefficiencies at the relatively less-skilled center position.

Of course, for every prophetic vision (Baker played a majority of his NBA minutes at center), there are troves of regretful selections and justifications lining the Usenet draft archives. In 2002, a 15-year-old named D.J. Foster had the no. 1 pick as the Houston Rockets GM. He selected Caron Butler instead of the overwhelmingly presumptive choice, Yao Ming. “This is like someone finding your diary, but it’s just filled with awful basketball takes,” Foster, a Ringer contributor, said. “I was 15. There was obviously no editing or vetting done. Why did they let me have the first pick?”

The degree to which Usenet drafters took their roles as scouts and GMs seriously varied heavily. “I always had at least one GM who just vanished and would not respond to email,” Simpson said. “I had an idea if the GM was going to ghost me.” Simpson would have contingency GMs he would break in case of a no-show in the final days of production, which involved coding thousands upon thousands of words from plaintext to raw HTML. The draft became Simpson’s unpaid second job—in the month leading up to every draft, he’d spend every night organizing and coding until bed.

For a select few, the Usenet draft was an exercise in testing the bounds of creative license: “All right, I’m going to confess something I probably shouldn’t say, but I’m gonna because, what the hell, it was 25 years ago at this point: I completely made up one of the scouting reports I did.”

“It connected a lot of like-minded people who were obsessed with very particular aspects of thinking about the game. And they all kind of thought about the game in the same way.” — Rob Clough

That’s Alan Sepinwall, Rolling Stone’s chief TV critic and former Usenet GM of the New York Knicks. At the end of his freshman year at Penn, he waited in line to register for an email account, which the university had only recently opened up to non-engineering students. He stood in line right next to Stephen Glass, future New Republic journalist turned pariah, whose stories and sources were revealed to be complete fabrications. Usenet “was a way to find people who were passionate about the stuff that I was passionate about who weren’t necessarily going to school with me,” he said. “So if I wanted to read about the Knicks, or basketball in general, or cop shows geared at middle-aged men, this was where I had to go.”

In the summer of ’94, Sepinwall interned with the New York Post’s entertainment desk. (He’d write a feature about rec.sport.basketball.pro for the newspaper later that summer; a framed copy of the story hangs on his mom’s office wall to this day.) “I remember saying, ‘Hmm, I’m just gonna tell people [on Usenet] that I talked to the Knicks beat writer, and they really like Gaylon Nickerson.’ I have no idea why I did this. So I was definitely not taking it as seriously as I could have, because the sports department was, like, three desks away from me.

“I feel like for other drafts, I had genuinely looked into it,” he continued. “But that was the one that, for whatever reason, I just turned full fabulist, and I guess I blame my association with Steve Glass on that.”

But even Sepinwall’s faux-intel came from somewhere; as Knicks GM, his justification for selecting Nickerson echoed all the major points of Jazzy J’s scouting report. “I was getting as much from the other posters as I was from traditional media at that point,” Sepinwall said.

In the 1990s, Jonathan Givony was obsessed with his hometown NBA team, the Miami Heat, which played its inaugural season when he was only 7. The team, however, wasn’t exactly in position to offer much in return for his devotion. “They just sucked so hard,” he told me. “So the draft was kind of a thing where I was like, these guys stink. How can they get better?” He followed the draft the only way he could then, by running to the front door for the Sun Sentinel and rifling through Ira Winderman’s predraft intel columns. “He was like a god to me,” Givony said.

In 1994, the same year the Usenet draft had hit its stride, Givony’s family relocated to Israel. He was 12. His new home was in the middle of the desert, with a TV that had only two or three channels—none of which broadcasted much basketball, if any. His fandom was largely put on pause; it wasn’t until he returned to the U.S. at 19 when it picked back up. Givony soon became a regular on the Hoopsworld and RealGM message boards—the latter of which had an active and dedicated NBA draft board.

Fast-forward 10 years. Simpson, after 12 years at the helm of the Usenet draft, finally bowed out. Clough, an original scout and GM and close friend despite their bitter UNC-Duke rivalry, agreed to take the reins for 2004. As more and more national columnists had their draft profiles published online at the turn of the century, the need for scouting submissions diminished. But Clough was still desperately looking for something new. He stumbled upon a website complete with comprehensive reports and occasional interviews on the most relevant prospects in the U.S. and abroad. It was Draft City, a website that Givony had just started up at the end of his freshman year at the University of Florida. “It’s incredible that anybody took the time to read what we had to say,” Givony said. “It was so haphazard, but people did take it seriously. All these journalists started reaching out for quotes, parents were getting angry, agents sending emails. So I was like, ‘Shit, I’d better start taking this seriously if people are going to take me seriously.’”

The NBA draft’s international boom was at its peak, and it quickly became a space in which Givony separated himself from the competition. Having spent his teenage years abroad, Givony was rankled by the coverage that non-U.S. players were receiving. “Every guy is the mystery man,” Givony said. “It was a lot less professional than the way people were to college players. I thought this was terrible, so I really worked at it.” That year, he’d caught wind of Peter John Ramos, an up-and-coming center prospect from Puerto Rico through RealGM’s Miami Heat board. He arranged for someone in the forum from Puerto Rico to film some of Ramos’s games on VHS and mail them over. “I thought he was going to be this great player,” he told Grantland in 2014. (Last month, Ramos effectively retired from basketball to become a Qatari pro wrestler.)

Clough was impressed. Rather than gathering piecemeal scouting reports from strangers or excerpting lines from magazine writers, he opted to link directly to Draft City player profiles with their permission.

“The interviews, the videos, and above all else, his level of objectivity I thought was remarkable and kind of spurred the kind of drafts that we have now,” Clough said. “The Ringer’s draft is excellent, The Athletic’s draft is excellent. People really put a lot of time and thought into this in a way that they didn’t before—and I think that’s kind of the legacy of the Usenet draft.”

It’s a miracle the Usenet Mock Draft lasted as long as it did. Merzbacher, Simpson, and Clough—all three of the draft commissioners—described the process as “a pain in the ass.” Given all the work that went into the draft, the birth of Simpson’s son at the end of 1997 probably should have been the end of an era. “As my son got older, my desire to spend all nights working on the draft began to wane,” Simpson said. “However, this was my one claim to fame.” And in an online landscape much, much smaller than today’s, that meant something. The Usenet draft’s entire history (sans its humble 1991 beginnings) is archived on ibiblio.org, a digital library project operated by UNC; while it was active, the Usenet draft was among the most popular ibiblio attractions.

As more and more universities opened up email availability, the standards of discourse and etiquette that had been established over years of community-building eroded. The signal-to-noise ratio shrank. September became a time of trepidation. “Every fall there’d be an influx of new students who were getting email accounts for the first time and getting Usenet access for the first time. And, you know, they’d be 18-year-olds,” Clough explained. “There’d always be this moment of dread: Here comes the next wave. Some of those people were great and brilliant, and other times they were 18-year-old trolls.”

The true deluge came when access expanded beyond the firewalls of academia. “During the time that I was spending a lot of time on Usenet was the rise of AOL, and with AOL came the phrase ‘Perpetual September,’” Sepinwall said. “There was just constantly people showing up on the basketball group, on the baseball group I was on, the TV groups—asking the same goddamn questions that had come up again and again. You started to see the old heads, who turned up a lot in that area at the time, basically saying, All right, we’ve got to find a new place to play, because this is becoming untenable.”

For many rsbp OGs, like Merzbacher, Simpson, and Clough, that new place was a private listserv of roughly 20, shamelessly called Hoopgods. The mailing list continues to this day, and each passing year since 1993 has culminated in a group outing to the NCAA tournament. This year’s destination, before everything changed? Cleveland. “The big joke is that we were still in Cleveland,” Merzbacher said. “That we actually have never left Cleveland.”

Among the Hoopgods are professors, writers, software programmers, an explosives detection expert, a chief of nephrology. Tai, who provided a decade’s worth of stats to the project, is also on the list. He’s stayed the course, and now works the basketball scouting and recruiting beat out in Oregon, previously having contributed as a writer and editor on the NBA’s official draft guides for 11 years. Together, once upon a time, they built a basketball-obsessed community within the ether.

“It was just a moment in time that was a little more provincial, a little more restricted—and, to be frank, a lot less diverse—than what the web offers us now,” Clough said. “But the positive of that provinciality is it connected a lot of like-minded people who were obsessed with very particular aspects of thinking about the game. And they all kind of thought about the game in the same way.”

Though interest was waning by 2004, Clough still did his best to fill spaces in his one year as commissioner. There was hole in the Usenet Miami Heat front office; given all the attention he’d funneled to Draft City, it was only right that Clough offered Givony an opportunity to fix his beloved team. And so, with the 19th pick in the 2004 (and final) Usenet NBA Mock Draft, Jonathan Givony selected Peter John Ramos. In hindsight, it was a passing of the baton. Soon thereafter, the Usenet Mock Draft was left to die. Givony, now of ESPN, would go on to become one of the most respected draft experts on the planet.

By 2004, Perpetual September had come for the Usenet draft. For Givony, it was only the beginning of his Perpetual June.

Danny Chau used to work here. These days, he’s just a friend.