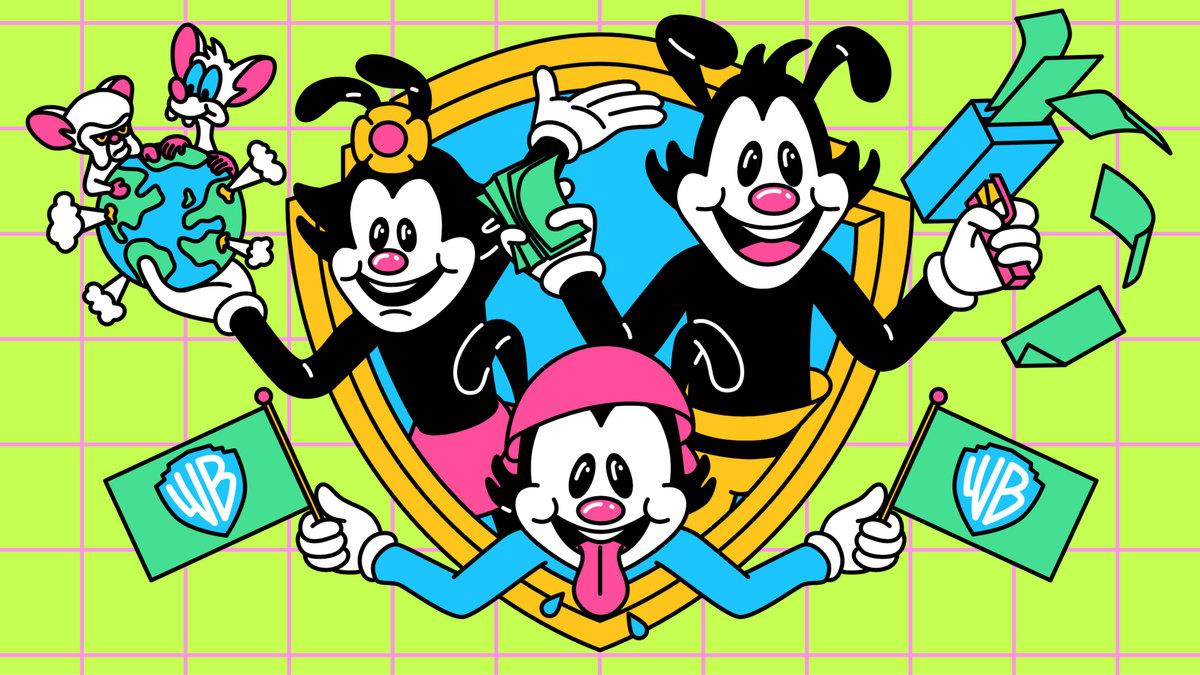

‘They’ll Get It at 8 or at 38”: How ‘Animaniacs’ Introduced a Generation to Comedy

Ahead of the ’90s animated series’ reboot on Hulu on Friday, the key players in the original remember how it came together and why it set the stage for ‘Family Guy,’ ‘30 Rock,’ and so many other showsThe Animaniacs episode “Variety Speak,” which aired in September 1995 during the show’s third season, features a whole song about the weird inside baseball of Variety magazine. “‘Hix makes pix, but the flick needs fix,’ means someone made a movie that bombed,” Dot and Yakko sing in a call and response. “‘The veeps in charge are now at large’ means everyone involved is gone / ‘The plot conflicts, no beautiful chix,’ so it’s coming out on video soon / ‘They’re taking their licks, ’cause the critics say nix,’ and the editors are going to try to fix it in the mix.”

Bear in mind: Animaniacs was an afternoon cartoon that ran on Fox Kids and then Kids’ WB. “The edict from the top,” says Rob Paulsen, who voiced Yakko and Pinky, “was ‘don’t condescend to the audience.’ They’ll get it at 8 or they’ll get it at 38.” “It was the Warner Bros. mentality,” says writer Paul Rugg, who points out that the original Looney Tunes played in movie theaters before films like Casablanca. “Disney wrote specifically for kids. ... The Warner Bros. way is: If you look at a family, you know, the dad laughs when they’re watching it, and the kids look up at the dad and go, ‘Why is that funny, Dad?’ And he goes, ‘Well, you have to understand...’”

From 1993 to 1998, creator Tom Ruegger and his staff of sketch comedy writers took some of the timeless ingredients from Looney Tunes and the Marx Brothers, whipped them up in a blender with a can of high-energy zeitgeist Surge, and made an all-ages show that served as a gateway drug for ’90s kids into a hyper-meta, pop-culture-savvy, smarty-pants style of comedy. The show swung from the lowbrow of Wakko desperately searching for a toilet, to a parody of the highbrow Apocalypse Now—where the characters journey deep into the WB lot, run over Jim Morrison in a golf cart, flirt with Dennis Hopper, and confront a mad director in a parody-within-a-parody of Jerry Lewis’s infamous Holocaust drama, The Day the Clown Cried. “Are kids clamoring for that story? No,” says Ruegger. “But they’re liking it, because there are goofy little things in it.”

Twenty-five years after the show playfully flame-broiled the sacred cows of the ’90s, the Warner kids (and Pinky and the Brain) are back in a new reboot on Hulu. The target audience is grown-up versions of the kids who first got hooked on that comedic high, the ones who only now get all of the jokes that were once over their heads. And while the reboot doesn’t come from the same original creative team (aside from flying under the banner “Steven Spielberg presents”), its built-in hype and success will be entirely due to those maniacs who taught a generation its first lesson in comedy, primed them for everything from Family Guy to 30 Rock, and most of all, gave them something to chuckle at. “Animaniacs was the best creative experience I had,” says Ruegger. “We really were just making cartoons to make us and people laugh—and no one was telling us how to do them.”

Ruegger worked his way up the cartoon ladder at Hanna-Barbera in the 1980s, eventually creating A Pup Named Scooby-Doo in 1988, a Tex Avery–style show about the famous dog as a preteen. Meanwhile, King of Hollywood Steven Spielberg was being courted by Warner Bros. to make an animated film for the studio, which ultimately took the shape of the director producing a TV series based on the Looney Tunes characters as youngsters. Ruegger was recruited by the head of Warner Bros. Animation, Jean MacCurdy, to develop a show from that loose concept, Tiny Toon Adventures. “I went in and said, ‘Here’s what I loved about the Looney Tunes—the mayhem, the intensity, the great scores behind them, the rivalries, the comic animosity, the wise guy attitude,’” Ruegger recalls. “I basically said, ‘We want to recreate that, and we want to make shorts.’ No one was doing shorts at the time. Steven bought the whole package.”

That, above everything, was the goal. “Your job is to please Steven Spielberg,” Ruegger remembers Warner Bros. CEO Robert Daley telling him and MacCurdy. “That’s your entire job. If this show is a piece of shit, if this show is the biggest bomb on the face of the earth, and Steven’s happy—you’ve done your job. If it’s a success, even better.” And it was a success, winning seven Daytime Emmy Awards and earning a Primetime Emmy nomination, and resurrecting the animation department that gave the world Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig.

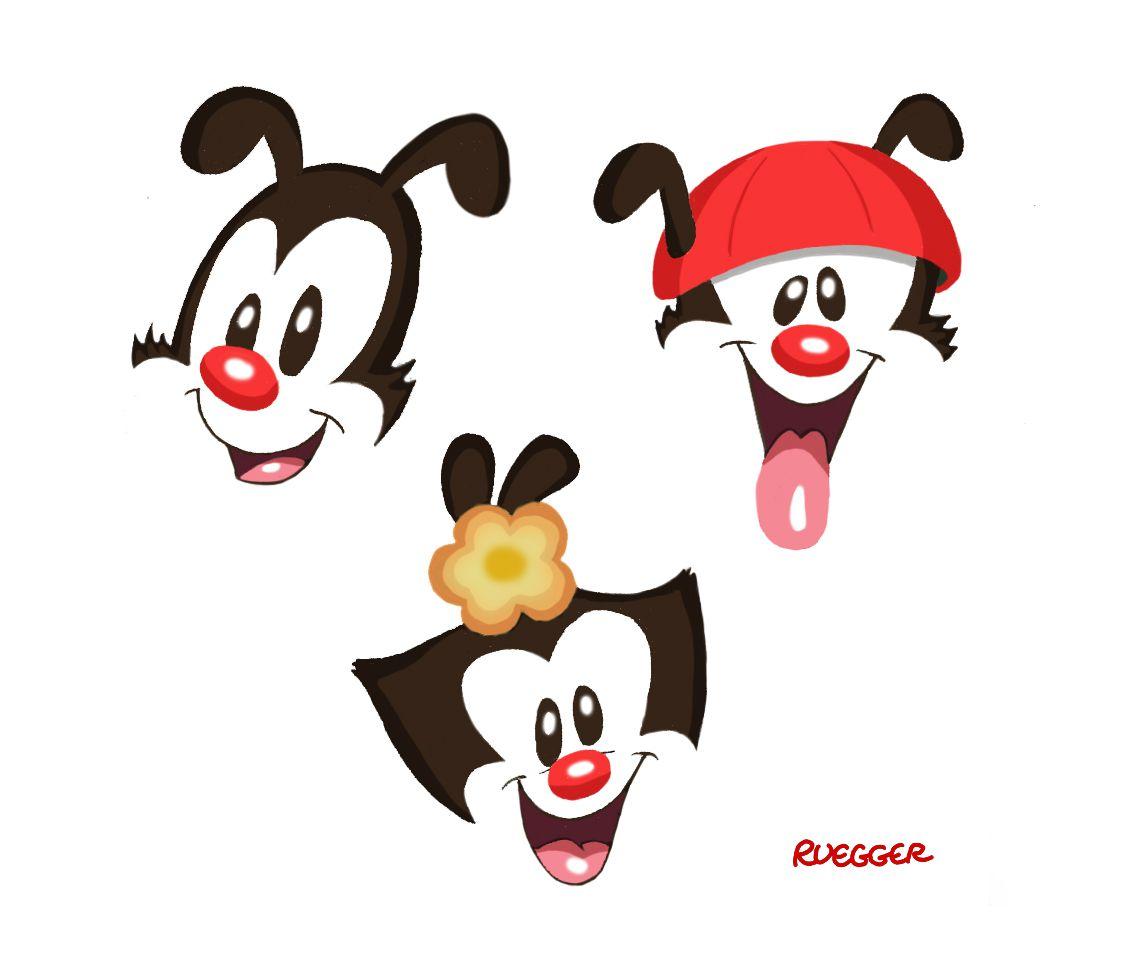

After that, of course, Spielberg and MacCurdy came to Ruegger wanting to know what was next. Ruegger wanted to make a show with brand-new characters, but Spielberg said they needed a marquee name. “A few days later, I’m walking across the lot, and I see the water tower,” Ruegger says. “I had what you’d call a cartoon epiphany, where it’s like, well, wait, there’s my marquee. I had already been planning on these three characters, created years ago, who were out of control, and I realized: If I can get Warner Bros. to OK the names of these characters as ‘the Warner Brothers and their sister Dot,’ there’s my marquee and my marquee name.”

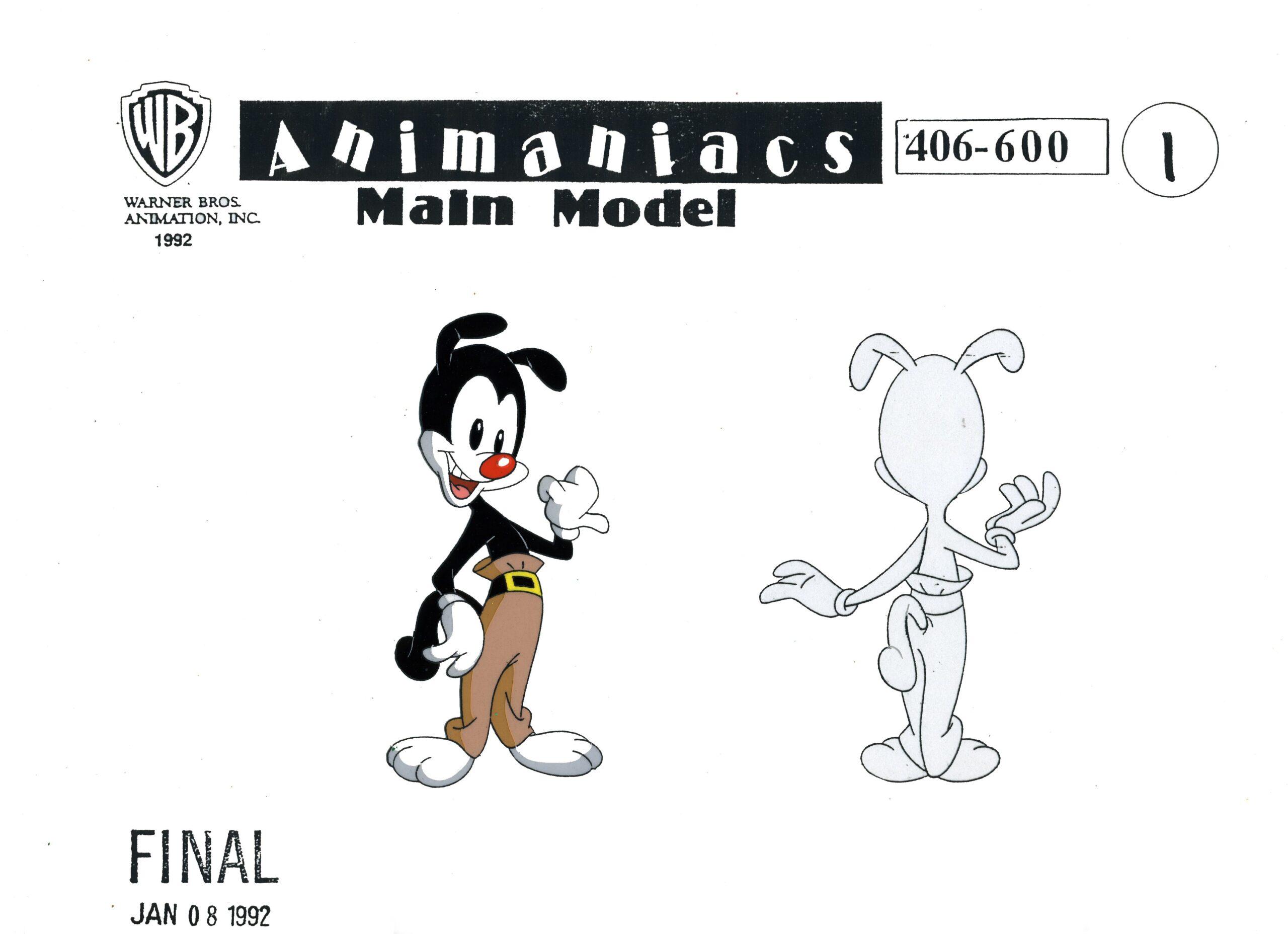

Yakko, Wakko, and Dot Warner resembled a trio of platypuses that Ruegger had dreamed up for his student film at Dartmouth, The Premiere of Platypus Duck, which is what landed him the job at Hanna-Barbera. They sort of looked like if Mickey Mouse had a baby with Bugs Bunny—in classic cartoon fashion, Yakko eschews a shirt and Wakko goes pantless—and the trio are constantly bouncing off the walls and tormenting adults with their childlike antics, intentionally misconstruing words into something ridiculous or naughty. In truth, they were partly inspired by Ruegger’s three sons, who he says “were at an age where they could really be annoying.”

As a kid himself, Ruegger would sit in front of the TV watching cartoons and drawing freehand. One particular subset of Looney Tunes came to be half of the inspiration for Animaniacs—the shorts announced with Daffy Duck photobombing Porky Pig in the WB rings. “Those cartoons were usually lunacy,” he says. “Daffy and Porky were a great combo, with Daffy sort of tormenting and being crazy. Those always meant a good laugh.” The other half? “Pretty much everybody that wrote for that show loved the Marx Brothers,” says writer-producer Sherri Stoner, “along with the old Warner Bros. style where they would step out of character and kind of comment on things. If you mash those two together, it’s sort of the genesis of the mood we were doing.”

We’d just come through the 1980s, an upbeat yet rather vapid decade, and were heading into a slightly more cynical time, certainly one where we as a society were employing more critical thinking.Maurice LaMarche

Stoner was an actress who started out on shows like Little House on the Prairie, as well as being the body model for Disney princesses Ariel and Belle. She was also a member of the Groundlings, the famous farm team for Saturday Night Live, alongside comedians such as Kathy Griffin and Deanna Oliver (the voice of Toaster in The Brave Little Toaster). Ruegger and Stoner first worked together when she wrote for Babs on Tiny Toons, and when Animaniacs rolled around he leaned on her to recruit the rest of the writers room. Stoner grabbed Oliver and Peter Hastings from the Groundlings, and John McCann and Paul Rugg from Acme Comedy Theatre—the “Valley version of the Groundlings” run by Stoner’s husband, M.D. Sweeney. (Second City alumnus Douglas Wood was also on staff.)

Rather than a traditional narrative show, Animaniacs would be a “magazine” variety show in the spirit of Rocky and Bullwinkle—full of franchises (Goodfeathers, Slappy Squirrel) and recurring gags (“Wheel of Morality,” “Good Idea, Bad Idea”), all built around the Warners and their free-range, fourth-wall-smashing antics. With almost carte blanche from Spielberg, Ruegger and his writers—most of whom had never written for animation before—were free to run amok on the studio lot themselves.

Ruegger deliberately wanted the show to have a sketch comedy feel, and Stoner says “the vibe while writing the show was the same vibe of being backstage at a Groundling show.” There was a “show bible” describing the different characters and franchises, but liberal interpretations were encouraged. Ruegger built the show on a “cartoon by cartoon” basis, mapped out on his office wall with index cards containing each short and its length. The team in Burbank got the shorts up to the storyboard, background, and layout phase (“That’s a lot of the cost,” says Ruegger. “A lot of the companies do not do that”), and then the actual, physical animation and coloring were done in either Chicago, Japan, Taipei, or Korea.

Each writer (or pair of writers) would pitch an idea to Ruegger, then go off and create the entire script—down to all of the visual gags and even the props in the room. “I would say, ‘Gosh, well I think I have this idea where Yakko, Wakko, Dot, they help Einstein ... or something?’” Rugg says. “It was that loose. I could speak for another hour and 15 years about outlines and the way it’s done now. I find it the most painful thing. But with Animaniacs, it was a notion of an idea. That’s all we had. And Tom would go, ‘Great. You have a week.’”

Like much of the staff, Rugg’s only prior experience was live sketch comedy, so he had to learn on the fly how to write for two dimensions. That proved to be a challenge—but also a liberation. “They don’t really do this anymore, which is too bad, but the writers would actually write all of the angles,” Rugg says. “You know, ‘angle on Yakko,’ ‘camera pans to door,’ ‘reverse angle on...’ It was really hard to get at first. I think my second script took me like a week and a half. But what it really did was it freed me to say exactly where the comedy was. For me, that’s the only way to write—going forward with that sort of show—was writing those angles, man. You’re in control of everything.”

“We were trying to make each other laugh,” says Ruegger. He would test jokes out on his young boys and gauge their reactions as a guideline. For example, despite not quite understanding it, they thought the bit in the theme song about how “Bill Clinton plays the sax” was, indeed, funny. Other writers would wait in their offices and listen as Ruegger read a new script. “And once he laughed, you knew, OK, I’m in a good place,” Stoner says.

“We didn’t really have any rules as to what we couldn’t do,” says Ruegger. “I mean, we weren’t going to do sex jokes, we weren’t going to do adult material. We were going to use our sophomoric, juvenile brains and create cartoons that we think we’d like to see, we think our kids would like to see.”

“We were left pretty much alone,” Stoner affirms. “Amblin and Spielberg were the only people really giving us notes. It was really the most creative job I’ve ever had. It really spoiled all of us, I think. After it ends, and you go out in the real world, well of course it’s nothing like that. It’s not an ‘anything goes as long as it’s funny’ playground, you know? There are rules and guardrails, and you hear ‘no’ more than ‘yes.’”

The typical Yakko/Wakko/Dot episode had the maniacs tormenting some authority figure—whether it was studio psychiatrist Dr. Otto Scratchansniff (Paulsen, channeling Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove) or historical figures like Beethoven or Picasso. There were no limits to what the Warners could do, what time period or genre they found themselves in, what celebrities they could impersonate, or what over-a-kid’s-head cultural reference they could make. “Whenever the networks had any kind of objection,” Ruegger says, “it would either be a legit objection, or if we didn’t agree with it we would say, ‘Well, Steven really likes this.’ And they’d say, ‘Oh, OK!’”

We were going to use our sophomoric, juvenile brains and create cartoons that we think we’d like to see, we think our kids would like to see.Tom Ruegger

The conceit of the show was that these characters, created by Warner Bros. in the 1930s, were so unruly they were locked away in the water tower for 50 years, and now were on the loose. “We knew we were going to rip Hollywood, because we had done that in Tiny Toons significantly, and no one ever squawked,” says Ruegger. “Steven never complained. So we’d inject him into some of the cartoons now and then.” That meant a ton of insider jokes about showbiz and the show’s corporate daddy, prefiguring modern sitcoms like 30 Rock lampooning NBC. In the Season 1 episode “Video Review,” the Warners run riot in a video rental store with a bunch of other “escaped” movie characters. Yakko, pursued by the T. rex from Jurassic Park, decides to drop a bunch of exploding “bombs” on the dinosaur—i.e., VHS tapes of Ishtar, Heaven’s Gate, and Spielberg’s own 1941. “He’s very self-effacing,” Randy Rogel, who wrote the episode’s title song, says of the director. “When you can make fun of yourself, that means you’re pretty secure.”

Spielberg read and approved every script, giving copious notes to Ruegger. “He was just a fountain of ideas,” says Ruegger. “And you could use maybe 20 percent of his ideas, because the other 80 percent were almost insane.”

Animaniacs’ carousel of franchises included Buttons and Mindy, a dog who rescues a little girl from high-stakes danger, and Rita and Runt—a theatrical cat voiced by Bernadette Peters, and her dimwitted dog pal, whose voice (by Frank Welker) was inspired by Dustin Hoffman’s character from Rain Man. But Spielberg’s personal favorite was Pinky and the Brain, the Laurel and Hardy–esque lab mice (“one is a genius, the other’s insane”) who continually plot to take over the world. On the set of Schindler’s List in Poland, Spielberg would play the recording sessions—with Paulsen as Pinky and Maurice LaMarche as the Brain—for his crew to supply levity. “That is a high compliment, as you can imagine,” says Paulsen.

The mice were inspired by a writer duo on the Tiny Toons staff. “Tom Minton spoke very low, very quietly. He’s very funny, but you’d have to lean in close,” says Ruegger. “And Eddie Fitzgerald was a good friend of his, who was much more vocal and boisterous. And so they’re in the next office, and Tom would say something that Eddie would find very funny, and Eddie would just explode. He’d go ‘Narf! That’s amazing, Tom!’ I mean, he literally said the word ‘Narf.’ I thought, what are they doing in there?—because Tom’s whispering. It’s like they’re planning to take over the world.” Bruce Timm, a character designer at Warner Bros. Animation who also cocreated Batman: The Animated Series, would do caricatures of everyone in the office. Ruegger took Timm’s sketches of Fitgerald and Minton, put red noses and ears on them, and voila! Pinky and the Brain. The duo was so popular that they got spun off into not one but two of their own series. (Pinky and the Brain ran for four seasons; Pinky, Elmyra & the Brain ran for one.)

Cartoons are a unique dance between writing, animation, and vocal performance. The actors who give life to cartoon characters are among the most talented and versatile performers in showbiz, and Animaniacs boasted a killer cast of voice actors with multiple-personality genius and singing chops—most of whom have joined the likes of Mel Blanc and June Foray in the art form’s hall of fame.

LaMarche had long been obsessed with the infamous recording of outtakes of Orson Welles doing a commercial for Findus frozen foods. “I must’ve listened to it nonstop in my car for a year,” he writes in an email. When he went in to audition for the Brain, “I looked at the initial design of the character—that furrowed brow, those jowly cheeks—and I was sure they’d created an Orson Welles mouse just for me.” In retrospect, he’s glad he never met the man who actually inspired the Brain before his audition. “Tom Minton’s a lovely guy, and yes, probably a genius—but his voice would not have carried this show.”

As for Paulsen, a lifelong fan of Monty Python and other British comedy acts, he decided to do a chirpy English accent in his audition for Pinky. “The lovability Rob brings to Pinky makes the Brain that much more palatable,” says LaMarche. “You look at the two of them, and even though Brain is a sarcastic, bitter, myopic, snobbish, obsessed, if highly intelligent character, the fact that Pinky seems so devoted to him means maybe you can kind of take Brain into your heart, too.”

Paulsen was a singer and impressionist who started his acting career in live action before landing voice-acting roles on G.I. Joe, The New Adventures of Jonny Quest, and the original Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles animated series. He knew Ruegger and casting director Andrea Romano from his gig as Fowlmouth on Tiny Toons, and he auditioned for Animaniacs alongside pretty much every other voice actor in town. It was “the first and only time in my career, to this day, where I have gone to the producers—who were my friends, whom I’d known—and I said, ‘If you don’t hire me for this, you’re making a mistake.’” He says landing the star role of Yakko, which let him combine all of his talents into one pint-sized package, changed his life. “It was the absolute embodiment of: Holy shit, I’ve been doing wacky stuff like this since I’ve been 12, just because it made my soul happy.” Paulsen imbued Yakko with an air of Groucho Marx without doing a straight-on impersonation. “We’re both smartasses,” he says of the character, “and not, I don’t think, in an ugly, bad way.”

Tress MacNeille, a voice-acting legend whose credits include Chip on Chip ‘n’ Dale Rescue Rangers and Agnes Skinner on The Simpsons, was the only top-billed actor on Tiny Toons who migrated over to Animaniacs. She had to audition like everyone else, but she had a feeling that Stoner—who followed in her footsteps at the Groundlings and wrote for her character Babs Bunny—wrote Dot with her in mind. “I had to play Dot,” MacNeille says. “There was really nobody else who could.” Stoner remembers hearing the audition tapes for Tiny Toons, “and Babs had to do, let’s say, five impressions in this little sheet that we wrote up,” she says. “When Tress did it, it was so whip-fast that I was convinced that Tom must have edited the track. He said, ‘No, that’s her doing this thing.’ It was just amazing to me. And she was just such a joy to write for.” MacNeille wound up voicing not only Dot, but “pretty much every girl in the show.”

Jess Harnell was the newest kid on the block, who first made a living doing soundalike songs for commercials in the late ’80s, singing as everyone from Axl Rose to Frank Sinatra to Michael Bolton. Disney hired him to sing principal parts in the then-brand-new Splash Mountain ride, and his cartoon career took off from there. He was invited to audition for Animaniacs and said he wanted to read Wakko “because (a) I love the name, and (b) he doesn’t wear any pants. Those are two very important things to me.” He seized on the character’s wacky look and at first tried out a “crazy, high-energy voice,” but Romano encouraged him to try some of his singer impressions. It was his John Lennon, given “a shot of helium” to fit the character’s small stature, that won the day.

Paulsen, MacNeille, and Harnell—all gifted impressionists and improv comedians—would always record their parts together, which gave Animaniacs a live-wire, sketch-ensemble energy. The writers knew they could basically have the trio do anything, and become anyone, and the performances in turn gave the animators wild and “zany to the max” material to cartoonify. The result was a ’90s Looney Tunes shot through with unencumbered Monty Python– and SNL-caliber performances.

In 1995, The New York Times noted that more than 20 percent of the Animaniacs audience was adults 25 or older. “Yes, we were definitely writing a show for kids,” says Rugg. “But we forgot about the kids most of the time.”

For the youngsters who were watching, the effect of that approach—making a kids show but not really trying to make a kids show—was profound. Animaniacs introduced them to a sarcastic, meta, insider form of comedy that was very much of the decade, and would become the norm of the 21st century. David Letterman was doing it, Mystery Science Theater 3000 was doing it; Animaniacs simply coated that comic ethos in candy and delivered it on weekday afternoons. “We’d just come through the 1980s, an upbeat yet rather vapid decade,” says LaMarche, “and were heading into a slightly more cynical time, certainly one where we as a society were employing more critical thinking. Add to that—and this may seem a weird observation on my part, but bear with me here—I think half the entertainment industry was also getting clean and sober all at once, so the writing was starting to get smarter and more real in TV, overall.” The Spielberg mandate was—instead of just passing the time with kiddy pablum in a ploy to sell toys—to make a show that was both accessible and sophisticated, funny and smart.

There is real simple stuff that’s real funny if you’re 5 years old—but then, under the surface of that, when you’re 25 and 50 you go, ‘Did they seriously just say that while they were running up that wall sideways?’Jess Harnell

“We weren’t locked into a certain way to tell their story,” says Rugg. “If you have Yogi Bear and Boo-Boo, it’s like: They always want honey, and they’re always going to talk to the ranger—and that’s kind of it. ... The other great thing about Yakko, Wakko, and Dot was they could comment on the sketch as it happened. If something wasn’t working, or as you were writing, you’re like, ‘That’s a really lame joke’—then I would sometimes go, ‘Well, geez, I think Yakko should comment on the fact that we tried a really lame joke.’ And that was absolutely the most freeing thing ever.”

They could also get away with some risqué humor and innuendo—Paulsen likes to cite the “fingerprints”/“finger Prince” gag—but Stoner argues that wasn’t the norm. Animaniacs wasn’t as “adult” as its big brother at Fox, The Simpsons, and certainly not as crude or explicit as later shows like Family Guy or Rick and Morty. Years after the show ended, Harnell remembers getting an offer to reprise Wakko on “a popular show that’s very edgy and mean-spirited and satirical,” he says, declining to name the series. “They were gonna do, like, ‘Whatever happened to the Animaniacs?’ and Dot was a streetwalker, and Wakko was in a bell tower with a gun, shooting people. They offered us a good chunk of money. And I said, ‘No, I don’t want to do it.’ And I found out later that day, without speaking to each other, that Rob and Tress also said no. The characters mean something to us.”

After five seasons and eight Daytime Emmy Awards, Animaniacs ended in November 1998. Spielberg had launched DreamWorks Pictures by then, and his days with Warner Bros. Animation were over. (Ruegger left WB in 2000.) After that, the show continued to circulate and find new fans online; the voice cast and creative team could often be found at Comic-Cons over the years. Paulsen always got a big response when he broke into Pinky or “Yakko’s Song” while recording his podcast (Talkin’ Toons) live at The Improv in Hollywood, and a few years ago he and Rogel took a concert of Animaniacs songs around the U.S.—sometimes as intimate piano gigs, sometimes with symphony orchestras. That was one of many catalysts for Spielberg and Warner Bros. to resurrect the characters, who make their rebooted debut on Hulu this Friday. The principal voice cast are all back, as is Rogel and original series composers Steven and Julie Bernstein.

As for Ruegger: “We assumed, should [a reboot] come to be, that they would automatically just call us and have us make it,” he says. “That was an incorrect assumption. So, by the time we even heard about it, it was like a done deal.” (Warner Bros. and Amblin own the rights to the characters.) “It actually hurts,” says Stoner. “These characters are in our DNA, you know. This stuff is all born out of sketch comedy, and out of our blood and sweat, right? And then it’s just given away.” The new showrunner is Wellesley Wild, a former executive producer on Family Guy—“so he’s naturally going to bring that little edgy side,” says Rogel.

Whatever the fate or quality of the new series, the original Animaniacs—also streaming on Hulu—is a gift that keeps on giving. Fans who were young when it first aired can watch, for instance, the Season 5 episode “Hooray for North Hollywood, Part 1”—and, for the first time, laugh knowingly at gags about Showgirls screenwriter Joe Eszterhas “never working in this town again,” Quentin Tarantino, back-end points, Disney CEO Michael Ovitz, and a whole song about schmoozing. “There is real simple stuff that’s real funny if you’re 5 years old—but then, under the surface of that, when you’re 25 and 50 you go, ‘Did they seriously just say that while they were running up that wall sideways?’” says Harnell.

“There was this one moment, I remember, we were all standing in the parking lot of the studio,” Harnell continues. “I was pretty new to the game—I’d been playing in bands my whole life, and singing commercials—and Rob and Tress were so seasoned. And we all looked at each other, and I went, ‘It doesn’t get much better than this, though, right?’ And they went, ‘No. This is as good as it gets.’”

Tim Greiving is a film music journalist in Los Angeles and a regular contributor to NPR, the Los Angeles Times, and The Washington Post. Find him at timgreiving.com.