Henry Louis Aaron has died at age 86. He was one of the greatest baseball players who ever lived, and saying so sells him short. Joe Morgan, the dynamic two-time MVP who died last October, is also one of the greatest ballplayers of all time—one of just 21 position players to collect 100 career bWAR, and one of just 10 to do so since integration. The difference between Aaron’s career bWAR and Morgan’s is greater than the difference between Morgan’s career bWAR and Sal Bando’s.

Hank Aaron’s legacy is tied up significantly in the numbers: primarily the number 755, the career home run record he retired with in 1976 and held for more than three decades. Less celebrated but no less impressive: his 3,771 career hits and 13,941 plate appearances (both third all time); and his 2,297 RBI, 6,856 total bases, and 1,477 extra-base hits. MLB has been a going concern for almost 150 years, with almost 20,000 total players. Aaron’s got more career RBI, extra-base hits, and total bases than any other. No caveats about era or adjustments for offensive environment are necessary. There’s the pile, and then there’s Aaron at the very top.

But let’s step back from the numbers, if that’s possible, and go back to the eye test.

This picture was taken in 1951, as Aaron was preparing to leave for his first season of fully professional baseball, with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League. The monochrome film, train carriages, and Aaron’s plain, utilitarian clothes almost make it look like he’s leaving for the Western Front of World War I. Aaron was only 17 years old when this picture was taken, and looks even younger. As a skinny teenager who’d grown up poor in Jim Crow Alabama, he was positively swimming in clothes that looked like they’d been borrowed from someone twice his size, and his prodigious power-hitting numbers belie the fact that even when he filled out, Aaron was listed at only an even 6-foot and 180 pounds.

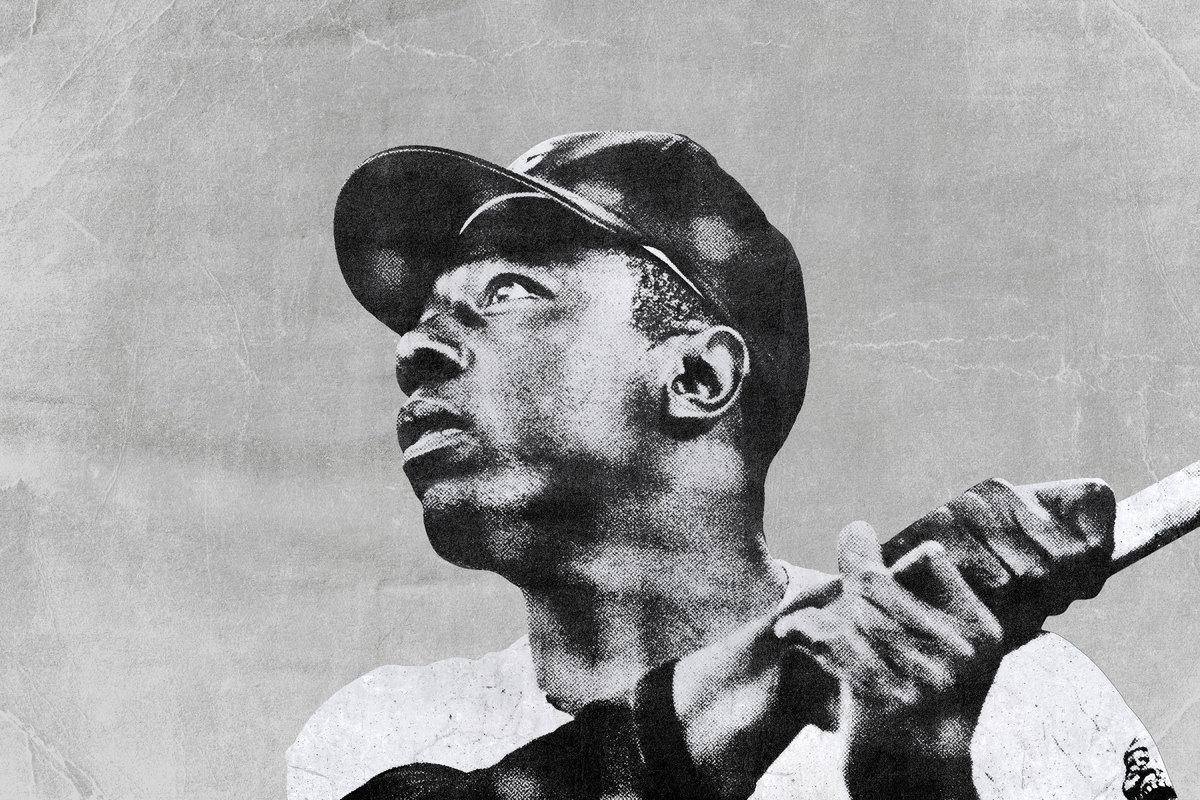

A few months later, Aaron posed for an official photo in his Clowns uniform. His dark blue pants and shapeless cap looked like something Tris Speaker might’ve worn 40 years earlier. The most famous bit of folklore from Aaron’s formative years is that he learned to hit with his hands reversed on the bat handle. Right-handed hitters put their dominant hand on top; Aaron learned to hit with his left hand over his right. This story gets told either to illustrate how talented Aaron was—so good he could hit with his hands backward—or to explain how he developed his trademark quick hands and strong wrists. It’s also a measure of how early in baseball history he came along. Nowadays, with rigorously organized youth baseball, a kindergartener would be coached out of such a habit within minutes of picking up a bat. But back in the 1930s and 1940s, Aaron tore through sandlot games and segregated high school ball, and even broke into a Black semipro team in Alabama hitting with his hands upside-down.

Aaron lasted only a few months in Indianapolis. As soon as Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby broke the color barrier, clubs from the National and American Leagues began scouring the Negro Leagues for talent. After Robinson came Monte Irvin and Don Newcombe, and after Newcombe came Willie Mays and Ernie Banks, and so on. In June 1952, Aaron signed with the Braves and spent a season and a half in their minor league system.

On April 13, 1954, Braves manager Charlie Grimm wrote Aaron into the Opening Day lineup in left field. Aaron was just two months removed from his 20th birthday, just 27 months removed from that photo of a skinny kid squinting into the camera at the train station. And from that day, and every other day for the next 20 years or so, Henry Aaron was one of the best baseball players in the world.

Aaron hit .280/.322/.447 for Milwaukee in 1954 and finished fourth in Rookie of the Year voting. In 1955, he made his first of 25 All-Star teams. (From 1959 to 1962, there were two games per year, allowing Aaron to appear in more All-Star Games than he did MLB seasons.) In 1956, he had his first 200-hit season and won his first batting title. In 1957, he led the league in home runs for the first time, won his only World Series, and won his first (and despite 12 other top-10 finishes, only) MVP award.

Aaron’s consistency is unparalleled in baseball history, and perhaps in all of North American team sports. He qualified for the batting title in each of his first 19 seasons, hit at least 24 home runs 19 seasons in a row, and scored at least 100 runs 13 times in a row. He hit .300 in 14 seasons, and he posted at least 6.0 bWAR every year from 1955 to 1969, a 15-year streak that nobody had matched before or has since.

Now consider this video. If you’ve been around televised baseball at all in the past 50 years, you’ve probably seen it. But watch it again. Decades removed from the Mobile train station, cross-handed hitting, and the Indianapolis Clowns, a 40-year-old Aaron took Al Downing deep to become MLB’s all-time home run king with his 715th, surpassing Babe Ruth.

When Aaron played his first MLB game, St. Louis was the league’s westernmost city. Games were played mostly during the day and broadcast primarily on radio. By 1974, MLB had added eight new teams, expanding to Texas and California and Quebec, split the leagues into divisions, and added a playoff round. (Aaron’s Braves—who had moved to Atlanta in 1966—played in and lost the first NLCS in 1969.) Aaron was now playing his games in a modern concrete stadium, wearing a modern polyester uniform designed for modern color television. When he hit his record home run, the electronic scoreboard celebrated the occasion.

The broadcaster on the call was Vin Scully, who announced games for Corey Seager and Joc Pederson just a few years ago. The man who caught the ball was Braves reliever Tom House, best known today as the coaching guru who taught some of the NFL’s most successful quarterbacks how to throw. The guy on deck was Dusty Baker, who managed Barry Bonds through his pursuit of Aaron’s record and is still in the game now, as manager of the Houston Astros.

Aaron bridged the ancient and the modern, entering a league with no amateur draft and only optional batting helmets, and ended his playing days as a designated hitter in a league about to be turned upside-down by free agency. And throughout it all, he was one of the best players in the league. He was also the last remaining veteran of the Negro Leagues in MLB when he retired in 1976. Aaron’s career spanned a period of de jure racial integration in baseball, and in the United States generally. During this time, white Americans were learning to launder their racism through codewords and legislative legerdemain, but the sentiments behind it were unchanged, and no less vitriolic.

Within the baseball world, the modern-day Hank Aaron is held up as a beloved patriarchal figure. In retirement, he went into private business and was less involved in baseball’s day-to-day operations than contemporaries like Morgan, Frank Robinson, or Al Kaline. But he was frequently around for interviews, ribbon-cuttings, and TV specials, in which capacity he received the respect and even awe due to a living legend. That treatment, purposefully or not, downplays the appalling racial abuse Aaron suffered as a player, particularly once he emerged as a threat to break Babe Ruth’s home run record. According to a 2014 CNN story, the Braves didn’t take down their “whites only” signs until 1961, and they celebrated their arrival in Atlanta in 1966 with a scoreboard message that referenced Fort Sumter and read, in part, “The South Rises Again.”

According to the U.S. Post office, Aaron received more letters than any other private citizen in the country as he chased Ruth’s home run record in the early 1970s—including nearly 1 million in a single year. A sampling of such correspondence includes a letter dated May 23, 1973, addressed to “Mr. N-----” and signed “KKK Forever.” Another correspondent implored the Braves, in 1972, to cut Aaron and replace him with “WHITE ball players who can use judgement,” capitalizing the racial epithets for emphasis. A third listed Aaron’s upcoming schedule and wrote, “You will die in one of those games. I’ll shoot you in one of them. Will I sneak a rifle into the upper deck or a .45 in the bleachers? I don’t know yet. But you know you will die unless you retire!!” The FBI combed through Aaron’s mail, investigating death threats and kidnapping threats against Aaron and his children, who went to school under police escort. Aaron himself started leaving the park through back exits and was accompanied in public by an armed bodyguard. Even when he broke Ruth’s record, he shrugged off two white fans who’d run on the field to congratulate him, as it was impossible to tell whether they intended to do him harm.

And it never really stopped. In 2014, Aaron told USA Today that he kept his hate mail, “To remind myself that we are not that far removed from when I was chasing the record. If you think that, you are fooling yourself. A lot of things have happened in this country, but we have so far to go. There’s not a whole lot that has changed.”

This interview sparked a renewed wave of hatred, including one email to the Braves’ front office that ended “My old man instilled in my mind from a young age, the only good [racial slur] is a dead [racial slur].”

“The bigger difference is back then they had hoods,” Aaron said. “Now they have neckties and starched shirts.”

In Cooperstown, Aaron’s plaque leads with his 755 career home runs and lists his other career achievements. Some of them, at least—Hall of Fame plaques aren’t that big, so not everything fits. And contained within the Hall of Fame archives is a sampling of letters he received during the home run chase. Aaron’s legacy is not just the numbers, relics of an extraordinary career spent dominating the game no matter how rapidly it changed around him. It’s the strength that led him through a society that changed far too little.