This week on The Ringer, we celebrate those movies that from humble or overlooked beginnings rose to prominence through the support of their obsessive fan bases. The movies that were too heady for mainstream audiences; the comedies that were before their time; the small indies that changed the direction of Hollywood. Welcome to Cult Movie Week.

Cult movies and the internet have gone together since the advent of dial-up: The first video ever streamed on the internet was a cult movie, according to a 1993 New York Times article that also explained what the internet was. Although most cinephiles celebrate that thousands of movies are now just a streaming service away, the ease of access to once-obscure films and far-flung fans has spurred an ongoing academic and critical discourse about whether the internet and streaming have killed cult cinema or fundamentally affected the way it’s experienced and perceived.

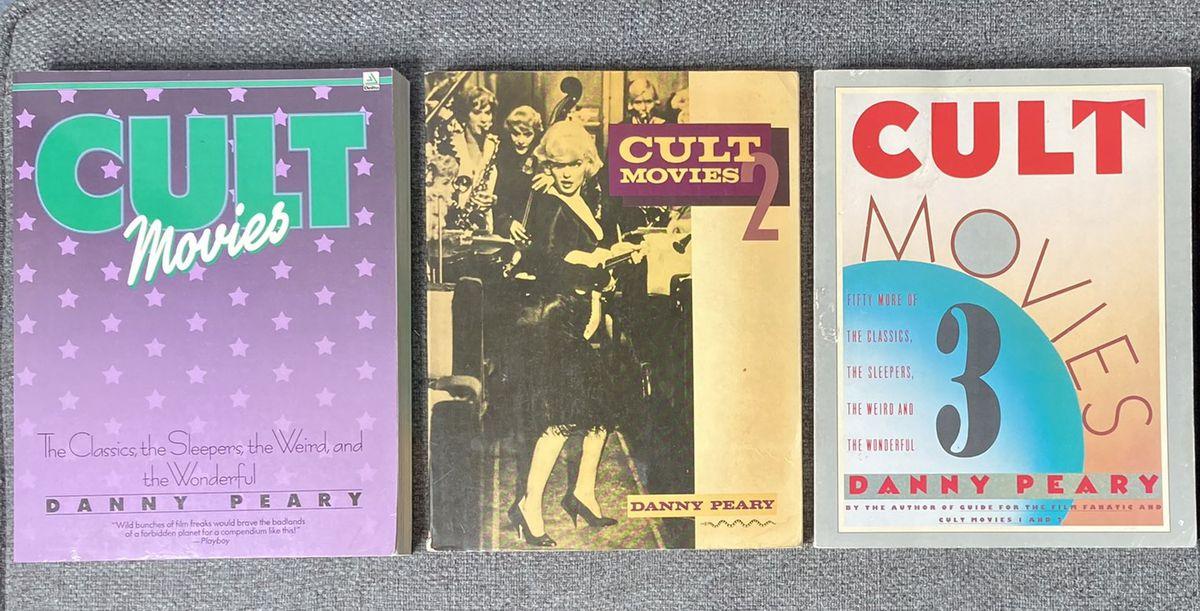

Long before broadband or dial-up, there was Cult Movies, a landmark book by critic Danny Peary. Peary, 71, has authored, coauthored, or edited more than two dozen books, mostly about movies or baseball. None of his work has resonated with readers more than the 1980s trilogy that began with Cult Movies (1981) and continued with Cult Movies 2 (1983) and Cult Movies 3 (1988). In Cult Movies, an oversized, 400-page paperback that remains revered by film buffs, Peary defined the inchoate concept of cult cinema and highlighted 100 “special films which for one reason or another have been taken to heart by segments of the movie audience, cherished, protected, and most of all, enthusiastically championed.”

Cult movies, Peary wrote, “are born in controversy,” and debates about what qualifies as “cult” continue. Peary, who opined about many more movies in the 1986 tome Guide for the Film Fanatic, no longer writes regularly about film, but he still updates his personal pantheon as new cult movies emerge and maintains a growing list of cult movies that weren’t covered by his books. It’s up to 10 pages. “I still get, ‘When are you going to write Cult Movies 4?’” Peary says. “I get that all the time.”

On the eve of the 40th anniversary of the publication of Cult Movies, The Ringer spoke to Peary about how he helped popularize the concept of cult movies and determine the cult canon, whether he thinks the consensus definition of cult movies has evolved since he first formulated it, and how the streaming age and the pandemic-imposed shift away from in-theater viewing may affect the future of cult movies.

I imagine you weren’t aware when you were writing Cult Movies that what you were doing would be as enduring and influential as it has been.

Back when I went to the University of Wisconsin, I wrote a bunch of articles. A couple of them were interviews, and a couple of them were articles for little magazines at the University of Wisconsin, and I was a film critic for the Daily Cardinal. And then I [was] the editor and coeditor of two books. Close-Ups: The Movie Star Book, which is actually my most successful book. And I did a book with my brother, The American Animated Cartoon.

Close-Ups was really successful, and from that I did Cult Movies. And the big thing is, could I write? Did I think I’d get a big following and become a cult figure myself and these books would be enduring? No, my worry was I couldn’t write. So I did these books, and the first one particularly got unbelievable reviews. That’s the big shocker. So I didn’t really think about 40 years ahead, that people would still be influenced in various generations.

Did you at least sense that you were onto something, that you were breaking new ground in some way?

I actually tried to do that. That’s the reason for doing the book. Close-Ups got a lot of fan mail. Cult Movies came around, and I started getting more fan mail. It was a repeat, but it was a completely different audience, and more people who were obsessive about movies and were actually grateful to me for writing about their favorite movies. And all the letters came with long lists of movies that should be in Cult Movies 2, and Cult Movies 3, and as I joke, Cult Movies 20 … all that. People were calling me up on the phone, just fans. So I was aware that there was an obsession involved, and people were like, “I can’t believe somebody finally wrote something about my favorite film.”

They were grateful, which was good, because I wasn’t always flattering to the films. They didn’t really mind that, and that’s amazing. So they said, “Though I disagree with you, I appreciate what you wrote, and I learned a lot, and next time I watch this movie, or watch The Wild Bunch for the 45th time, I’ll look at it differently,” that kind of stuff. So it was rewarding.

I wanted to be groundbreaking. I wanted to create a new genre, which is cult movies. Taking films from all other genres and putting them all together into one volume—some films that had always been loved by highbrow viewers and critics, and other titles which were adored by lowbrow cinephiles, and mix them all together. And people got to read about films that they never thought they’d care about, and to learn about films and be able to decipher them the way I did. Because if I could do it, other people could do it too. They just looked at films a different way and got a new appreciation for films.

“People were like, ‘I can’t believe somebody finally wrote something about my favorite film.’”

So many people became film critics themselves, and filmmakers said those books influenced them. They made them think about movies in a different way, and that was my goal. A lot of critics I don’t like to read, they write for each other. I wrote to the fans, to the readers of the book. People liked me, because I came out of nowhere. I wasn’t writing for a magazine. I wasn’t writing for a newspaper. They’d just say, “Who is this guy?” Basically nobody knew who I was, and so I had that advantage.

And then what I mentioned before about bringing all the genres together, because I always grew up liking every kind of movie. That was my advantage in these books, is that I knew low-budget horror movies, and I knew Citizen Kane. I could write about Texas Chainsaw Massacre and write about Citizen Kane, or write about Plan 9 From Outer Space or Aguirre, the Wrath of God. So I’m very eclectic, and that was to my advantage.

I created a new genre with titles from every other genre, as the commonality of these films was that they could all be written about, not just [as] “Was this a good Western? Was this a good science-fiction movie? Was this a good musical?” But also in terms of “Who are their fans?” So that was the other thing I always said: “Why do people like these movies in such a way?” That’s what I always went after, and that’s always part of my definition of the films that I defined as cult movies, or identified as cult movies, was that they can be written about in regard to “Who are the people that rally behind them and see them over and over again and share their views with other people?” So that’s what I was always going for, and I have to say it worked.

Would you say that you coined the “cult movie” term or concept? Or would you say that you helped refine it or popularize it? Were people already referring to things as cult movies?

It wasn’t a new term, for sure. But when the midnight movies came out, people were just talking about midnight movies. It was an interesting period of time, because you saw Rocky Horror Picture Show was the definitive cult movie. We heard the term “cult movie” over and over again, specifically because of the fans. But then you saw Eraserhead and El Topo. Night of the Living Dead slipped in there. The Harder They Come. What was interesting, I found, was that they all had different audiences. So that’s when I started thinking of it in terms of “There is something new going on, and it doesn’t have to do with losing money, because these movies were making money,” and they had repeat audiences.

I took those movies and thought of all the other movies that over the years we’d called cult movies that weren’t so obscure. Starting with Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which played seven years in one Paris movie theater. And the Humphrey Bogart cult, the James Dean cult. Humphrey Bogart films were shown at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, and that was a famous event. [Audiences] were all talking back to the different movies, they’d seen them so many times. They knew the dialogue to Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon, and Beat the Devil, which was always referred to as a cult movie. All About Eve had the same thing, it was talked about as a cult movie although it was a major, major, Oscar-winning movie.

Unlike what other critics had always been saying, I said cult movies are not obscure movies anymore that only the “real” cinephile person has seen in some dungy basement, but all kinds of films, which is why I put “The Classics, the Sleepers, the Weird, and the Wonderful” [in the book’s subtitle]. I have long definitions in each of my three Cult Movies books, and they’re a little bit different, in responding to all the criticism I got for how I defined cult movies. I never got criticism for the chapters themselves or what I wrote, but people, particularly critics—I became a target of what cult movies are. So my definition of cult movies became the definition, which was expanded. I made it much broader than it used to be. And not everybody liked it.

Do you think the definition, or your own definition, has evolved at all over the past few decades?

No. Well, people still argue about it. Even several years ago there was a whole debate in one of the magazines. They brought together a bunch of critics to talk about the definition of cult movies, and I was the main target, but I can take it. I knew that I was stepping out there and going to get rammed by it. But people basically like it. I wanted to write about the movies, and I had to come up with a definition. I know in my head what I think are cult movies, and do I ever think everybody’s going to agree with me? Of course not. So I’m fine with it. If it gets more attention for my books, that’s fine.

When you were writing the first book, you couldn’t just Google a list of cult movies. You had to generate your own.

Yeah, I wasn’t getting letters from people. Nobody knew I was writing this book. So it’s basically my 100 films, the major cult movies. I think I made a list of a bunch of films at the end of the book, titles that I couldn’t include. But people wrote with more and more and more titles. Some of these people—John Waters, David Lynch, and every horror movie, George Romero, John Carpenter—every film they make has a cult, so you can never satisfy everybody.

It’s so easy to find almost every movie these days. You can buy it, you can download it, you can stream it. So I wonder what you think about whether the difficulty of finding a cult movie is integral to its appeal, or whether the concept of cult movies can survive and flourish even when most movies are more easily accessible.

Some films have cults and you can’t see them, or they’ve been banned, so a cult comes around the Barbara Steele movies, or Wicker Man, and things that are banned so you never see the real version, the director’s version. You say, “It must be great, it must be great.” So there’s a reputation, and they’re out of circulation. The Searchers was out of circulation for a long time, and I had seen it and other people had seen it, and we all would tell people, “This is the greatest Western,” and nobody could see it. So it built its reputation a little bit. The movie M, the Peter Lorre movie, has different versions of it. So that becomes part of the conversation: “Have you seen the full version?” Freaks is another one that had different endings. There’s a Kenneth Lonergan movie called Margaret; a cult is building around that one now because people who have seen the movie love it, and it hasn’t been seen a lot. So it’s one of those movies that needs word of mouth to get seen, and word of mouth is always part of what becomes a cult movie.

When I did Cult Movies, people would use the titles as a checklist—“I’ve got to see this movie”—and see every movie in the book. So I would hear, including from filmmakers, that they would see that a movie is playing somewhere, like Deep End, which never plays anywhere. “What is Deep End?” They’d learn about this movie from my book, and they’d see it’s playing in some town way far away, and they’d go drive to see it because of the book. So that’s one of the things that my book would do, and one of the reasons films have cults is people would actually go a long way to see movies they’d heard about.

Guide for the Film Fanatic particularly was found in video stores. That’s when the VCR craze was starting and everybody was going to the video stores. So you’d find my books in video stores, and people could seek them out. “This store doesn’t have this film, so let’s go to another video store.” It was that seeking out and discovery aspect, which is always also part of cult movies, the thrill of discovery and then sharing your movies.

“Word of mouth is always part of what becomes a cult movie.”

At the time I did these books, no filmmaker really wanted to make a cult movie. They associated cult movies with not making a lot of money. But what happened over the years is the advent of the film festival, and the competition by independent filmmakers to get their films seen and get their films talked about. There’s so much competition, because everybody can make a movie. Everybody wants to be a filmmaker. There are a lot of film schools. When I went to USC, there weren’t a whole lot of good film departments around the country. Now there are lots of them, so there are just lots of kids making movies and trying to get into festivals. They all want to have cult movies at this point. To have success for that film, but also get your name known, and you can break into the film industry that way. So having a cult movie is now a goal for all the young independent filmmakers.

Now, online, I do these things where I do a recommendation. One of the ones I did was under-the-radar horror films, and I had lots of people contribute. Hundreds wrote in obscure horror films that they wanted to recommend to other people. I’ve seen hundreds and hundreds and thousands and thousands of horror movies, and there were a lot of titles I’d never heard of, never saw. And people had seen them and they wanted to share. Online, people are really eager to participate and say, “This is the movie I discovered and I want you to see.” So I think the potential for cult movies is still there. There are movies that become cult movies just through the dialogue online, people sharing. So that’s good.

My whole goal has always been to encourage people to see movies. I don’t like critics who say, “Skip this movie. See this other one.” I’ve never done the one-to-four-star ratings, because I think sometimes a film will get two stars that’s more interesting, or more original, than a film with three stars. Even with the films I didn’t like in the Cult Movies books and Guide for the Film Fanatic, I never said, “Don’t see them.” I never say “a waste of time.” Nobody minded when I didn’t like a film, particularly a cult movie, because I was respectful to the people who do like them, and I tried to figure out why they do like them. I say, “I don’t like it, but I can understand why it would appeal to other people,” and it obviously has appealed to other people, because they have cults. So I just make people aware of them.

It sounds like it was very validating for the readers of the first Cult Movies book to see those movies covered and to find someone else who had heard of them.

That’s exactly true. I always remember, I’d seen Little Shop of Horrors—the original, the Roger Corman one with Jack Nicholson and Jackie Joseph—many, many times, and I’d say, “Oh, it’s a natural for the Cult Movies books,” and I included a chapter on that. And then I always remember getting a letter from somebody who lived in a small town. In those days you didn’t have the internet, and you weren’t connected to anybody all over the country, and you couldn’t Google anything. So he wrote, “I love Little Shop of Horrors. I can’t believe anybody else has ever seen it.” He was excited enough to write me a letter about it. That’s how excited he was, that he wasn’t alone in being a Little Shop of Horrors fan. That wasn’t a common thing, but that just showed, that’s the way it was back then before the internet. You weren’t really connected to anybody but your friends and what was going around.

That’s probably a positive thing, that people can find these communities and like-minded people. They don’t have to feel isolated. On the other hand, you wouldn’t get that letter today from the person saying, “Oh, someone else knows this and likes this,” because they could easily find someone who knows it and likes it. So you might not get that hard-earned, euphoric feeling of finding your fellow fans.

It’s also positive feedback. You think back to the horror movies and science-fiction movies from the ’50s. We adored them as kids, but adults always looked down on you. “How can you like that trash?” Like your comic book collection. “How can you read that?” Adults have no concept. So I like the idea of elevating the lowbrow to where it deserves. That was a really good movie, Little Shop of Horrors, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and the original Thing, and all that. Them!, which was a big film in my childhood. So there was quality in a lot of those films that people, adults particularly, automatically [thumbed] their nose at. So their kids who loved them, they felt disrespected.

All of this started with the midnight movies, and the communal experience at those screenings. Because of the pandemic, those things are not happening, or not happening as much, and there’s some doubt about whether they’ll happen in the future. Obviously, there are other ways to see these things now. You don’t have to see them in a midnight screening. But it’s still a special way to see them. So I wonder what you think would be lost, if anything, if midnight screenings don’t survive.

We have giant screens at home now. And then movies will come out and you’ll say, “Look at how much money we’re saving by not going to the movie theater.” So there’s the danger that all the studios, I’m sure, are feeling, that people will get used to just watching stuff at home, and watching on your computer, watching a full movie on your little phone. You don’t go to video stores anymore. You just buy stuff online and get it sent to you.

So there’s all that going on, and it’s certainly easier. But there’s nothing like seeing a movie, particularly old movies, in a big theater on a giant screen. It was Rocky Horror Picture Show where I wrote about the democratization of communities at the movie theater. You could be rich, poor, it didn’t matter. Once you bought your movie ticket and went and sat in a movie theater, everybody is the same. And that’s bringing communities together.

During the pandemic you watch a lot of movies, and there are a lot of scenes in movie theaters where you’re watching people watch movies. They’re sitting side by side by side by side by side, and they’re completely crowded, and it’s every type of person you can imagine. Kids and older people, and then people making out, and people in suits. Just the escapism of going to a movie theater, and just being part of the crowd and just disappearing with everybody, but everybody’s kind of your friend. That’s what I like. That’s what we miss, is that community of just people all watching movies together. There’s something really special about that, and there’s a sense of equality. They’re all there watching the movie. So there’s no substitution for going to a movie theater and just sitting and enjoying a good movie.

This interview has been edited and condensed.