No year in hip-hop history sticks out quite like 1996: It marked the height of the East Coast–West Coast feud, the debut of several artists who would rule the next few decades, and the last moment before battle lines between “mainstream” and “underground” were fully drawn. The 1996 Rap Yearbook, a recurring series from The Ringer, will explore the landmark releases and moments from a quarter-century ago that redefined how we think of the genre. Up first, we’re exploring Tupac Shakur’s All Eyez on Me and the fall of Death Row records.

In the February 1996 Vibe magazine cover story on Death Row Records—the one that produced the indelible image of Suge Knight, Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, and Tupac Shakur posed like Goodfellas—writer Kevin Powell pauses to acknowledge the deference visitors to Knight’s office were expected to pay. “Right in front of his big wooden desk, outlined in white on the red carpet, is the Death Row Records logo: a man strapped to an electric chair with a sack over his head,” Powell wrote. “I was told by another journalist that no one steps on the logo. No one.”

What would happen should someone violate this rule is left unsaid, but anyone with even a passing knowledge of the players involved understood. Violence had been a founding principle of Death Row, which traced its roots to Knight strong-arming Eazy-E—and possibly threatening to harm his mother—to get Dre out of his contract with Ruthless Records, where the producer had redefined gangsta rap with N.W.A. It was omnipresent in both the label’s output, led by classics like The Chronic and Doggystyle, and in the surrounding drama—Tupac had just joined the roster fresh from prison; Snoop was awaiting trial on first-degree murder charges as the article went to press. Knight, of course, wanted it this way: Stories of him assaulting producers and rival executives hung over his every interaction. The man owned an attack German shepherd named Damu, the Swahili word for “blood.” “The mere mention of [Knight’s] name was enough to cause some of the most powerful people in the music business to whisper, change the subject, or beg to be quoted off the record,” Powell wrote. The near-constant threat of violence had served the physically imposing Compton native well as he rose from college football standout to bodyguard to mogul: As Powell noted, that electric-chair logo had come to represent a company worth an estimated $100 million.

At the time of the cover story, Death Row looked unfadeable. Not even four years old, the label was on an unprecedented run of success. All five of its full-length releases to that point charted at least in the top three on Billboard, all eventually going multiplatinum. Its music was everywhere—on MTV and radio in suburban markets, as it helped turn gangsta rap mainstream while changing the sound of West Coast hip-hop in the process. And Knight and Co. were now setting the narrative in the media—the Death Row camp had essentially invented their feud with the East Coast’s Bad Boy out of thin air, but it raised the profile of both sides, even if outsiders worried it could lead to real-life violence. From Sugar Hill to Def Jam to Profile to Ruthless, rap music had seen a handful of successful imprints in its young history, but none had become as famous—or as feared—as Death Row Records. The release of Tupac’s All Eyez on Me, the sprawling magnum opus that turns 25 this weekend, would be the final step in constructing an unstoppable, genre-crushing tank.

But that apex wouldn’t last long. 1996 would prove to be one of the most tumultuous times in rap history, with Death Row at its center. The label had its greatest triumphs that year, but also lost some of the key figures in building its legend. And while All Eyez on Me pointed to a bright future for both the artist and the label, it quickly became a tragic reminder of an otherworldly talent gone too soon. The album is many things: a rallying cry for an entire coast, a monolith that ushered in an era of blockbuster hip-hop releases, a classic that cemented Tupac as an all-time great. But like the Vibe cover, it’s also a snapshot of giants atop the mountain, unaware that the ground is about to crumble beneath their weight.

The sessions for All Eyez on Me were among the most frenetic in music history. Tupac Shakur—a rap and movie star who had become simultaneously one of the most loved and loathed figures in American culture, at once celebrated for his art and decried by the vice president of the United States—had landed on Death Row partially out of necessity, and partially because he wanted allies. He had spent most of 1995 in Clinton Correctional Facility in Upstate New York. The previous December, he had been convicted on two counts of first-degree sexual abuse for improperly touching a woman who said she was assaulted by Tupac and three associates in an NYC hotel room. He was sentenced to up to four and a half years in prison, with bail set at $1.4 million. (Tupac, who maintained his innocence but later said he could’ve done something to stop the assault, was also acquitted of sodomy and weapons charges stemming from the incident.) The rapper had also spent much of the year stewing: Just two nights before the jury handed down its verdict, he was shot five times in the lobby of a studio that Bad Boy Records’ Sean “Puffy” Combs and Notorious B.I.G. were working out of. While in Clinton, he became convinced the pair were at least aware of the plot against him (an accusation both vehemently denied).

That year, Tupac also watched his third album, the introspective masterpiece Me Against the World, reach no. 1 on the Billboard charts while he sat in a cell. The success meant little—not only was he behind bars, but he was nearly broke, supporting his family and paying out a massive amount of legal fees. He needed money so badly that the night he was shot, he was slated to record a guest verse for a rapper named Little Shawn for $7,000.

Suge Knight saw Tupac’s hardships as an opportunity. Throughout 1995, the Death Row CEO regularly made the 3,000-mile trek from Los Angeles to Dannemora, New York, to meet with Tupac. He had courted the rapper for years, dating back to when he paid him $200,000 for a single song on the Above the Rim soundtrack, which Death Row produced for a movie starring Pac. But now, with one of the brightest stars in music at his lowest point, the timing seemed perfect. Death Row’s parent company, Interscope, owned Tupac’s contract but wanted to distance itself from the rapper’s firebrand persona, so it welcomed its subsidiary’s attempts to sign him—after all, a deal with Death Row would essentially amount to paperwork shuffling. Suge, meanwhile, promised to alleviate Tupac’s legal and financial woes and even buy his mother, the Black Panther icon Afeni Shakur, a house. To further prove his loyalty, Suge made Tupac’s beefs his own—his infamous 1995 Source Awards speech calling out Puffy came shortly after a visit to Clinton. The diatribe may have reverberated throughout the industry, but it was intended for an audience of one.

On September 16, 1995, Tupac signed a three-page handwritten memo drafted by Death Row attorney David Kenner that served as a new contract. It gave him a $1 million advance and cash for other expenses in exchange for his next few albums. It also made Knight his manager and Kenner his attorney—clear conflicts of interest. Another one of Tupac’s attorneys would later tell The New Yorker that the arrangement was illegal and that Tupac only signed it “because he was in prison.” Tupac, however, was under no delusions about the arrangement. “I know I’m selling my soul to the devil,” he reportedly told one friend.

Within a week, Suge had procured the bail money for Tupac’s release, pending appeals. On the evening of October 13, the rapper touched down in his adopted home of Los Angeles. He went directly to Can-Am Recorders, the San Fernando Valley studio that Death Row had taken over and turned into something of a gangsta rap frat house. Within 45 minutes of his arrival, Tupac had laid down the first verse for “Ambitionz Az a Ridah,” a ready-made war anthem that invoked Michael Buffer and Mike Tyson, looked to settle scores, and addressed his shooting and recent conviction head-on. After finishing “Ambitionz,” he recorded “I Ain’t Mad at Cha,” a relatively more plaintive song that opens with a verse about a lost friendship. Tupac hadn’t even been out of prison for 24 hours and had banked two songs, both of which would go on to be classics.

That first night set the tone for the All Eyez on Me sessions, which took place over two weeks. Ben Westhoff describes the scene in his excellent 2016 book Original Gangstas: Fueled by cigarettes, weed, and Hennessy, Tupac would record into the early-morning hours, sometimes until the engineers would fall asleep at the mixing board. He’d often commandeer two studio rooms, having tracks ready to go in each and bouncing back and forth, knocking out songs as quickly as possible. He’d grow impatient if he had an idea but nothing to set it to, so he’d ask the engineer to record him to a click track and have the producers fill in the music later. All the while, he wrote at a feverish pace: Tupac reportedly emerged from Clinton with just one song ready to go; by the time recording wrapped on October 27, he had made dozens.

Many involved posited that those sessions were so prolific because Tupac was making up for a lost year, or because a return to prison was looming if he lost his appeals. Others thought he was simply at the peak of his powers, directing producers, singers, and guest rappers like a benevolent dictator. “You could tell he was really on a mission,” engineer Dave Aron told XXL in 2004. “He really had a real vision of what was going on, and he wanted to get a lot done in that short amount of time.” But there’s perhaps a simpler reason for that creative outburst: The handwritten contract Tupac signed with Suge called for three albums. The quicker he finished them, the quicker the arrangement would be over. As G-funk crooner Nate Dogg stated plainly in that same XXL retrospective, “He didn’t want to be on Death Row.”

All Eyez on Me was released on February 13, 1996, as the first double CD in rap history, fulfilling two-thirds of the contract’s requirements. Like its predecessor, Me Against the World, it would debut at no. 1, but the new album was exponentially more profitable—because of the hefty price tag for the two-disc set, All Eyez on Me brought in $10 million in revenue in its first week alone, making it the second-most successful opening in music history to that point, behind only The Beatles Anthology. Death Row had experienced success before—The Chronic peaked at no. 3 and eventually sold 5 million copies, while Doggystyle posted the best opening week ever by a debut record—but All Eyez on Me marked the pinnacle of the label as a commercial force. It would eventually be certified diamond, for 10 million units sold, which Suge considered to be the label’s crowning achievement. “Tupac was on Interscope the whole time,” Suge Knight bragged to Rolling Stone in 2013. “They couldn’t make him a superstar. But the minute I got Pac out of prison …”

Musically, All Eyez on Me shows off a different Tupac from the one on Me Against the World or the earlier, more socially conscious hits “Brenda’s Got a Baby” and “Keep Ya Head Up.” His soul-searching had mostly been replaced by chest-beating confidence. He’s sharper than ever—perhaps that’s partly owed to him devouring Machiavelli’s The Prince while in Clinton—but uninterested in saving the world, or even himself. All Eyez on Me is 132 minutes of nihilism and euphoria and charisma, sometimes all at once. That begins on “Ambitionz Az a Ridah,” which would become the first disc’s opening salvo, and continues throughout its 27 tracks: on ominous cuts like “No More Pain” and “Only God Can Judge Me”; on fun (if misogynistic) party-starters like “Skandalouz” and “All About U”; on sentimental songs like “Life Goes On” and the second disc’s closer, “Heaven Ain’t Hard 2 Find.” Perhaps the greatest testament to the music on All Eyez on Me is that it contains some of Tupac’s best album cuts, like “Shorty Wanna Be a Thug” and “Heartz of Men,” while boasting his best singles, notably “How Do You Want It” and the Snoop team-up “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted” (the latter of which alluded to the pair’s ongoing legal issues and pulled no punches regarding Puffy and Biggie in its video).

Pac had never sounded more like a star, but at the same time, Death Row had given him access to a stable of all-world producers to help him realize his vision. In many ways, Me Against the World was indebted to the East Coast vision of hip-hop—two of its tracks were produced by Easy Mo Bee, the man behind Bad Boy staples “Flava in Ya Ear” and “Warning,” and it included “Old School,” a dusty tribute to pioneering acts such as Eric B. & Rakim, De La Soul, and Whodini.

While Tupac had grown up bouncing around the five boroughs and Baltimore, he had become famous on the West Coast, where he relocated to in the late 1980s. By the time he entered Clinton, he was most closely associated with South Central Los Angeles and its music scene. All Eyez on Me called on renowned SoCal beatsmiths like DJ Quik, DJ Pooh, and Daz, the studio wunderkind who had just topped the charts as part of Tha Dogg Pound. More than a third of its tracks came from Johnny J, a South Central startup who had evolved into one of Tupac’s closest collaborators in the years after they first worked together on 1994’s “Pour out a Little Liquor.” At least a dozen different producers contributed to the album, but under Tupac’s direction, they crafted a cohesive sound—a kind of sophisticated G-funk that built on the blueprint of Death Row’s earlier classics. With the effortless grooves of classics like “Skandalouz” and “Picture Me Rollin’,” Tupac was finally able to fully embrace the sound of his city for the first time.

Largely absent from the album, however, is Dr. Dre, the man synonymous with Death Row. Dre had cofounded the label in 1992 with Knight, rapper the D.O.C., and industry veteran Dick Griffey with financial backing from incarcerated drug kingpin Michael “Harry-O” Harris, but the producer had become a rare presence at Can-Am by the time Pac arrived. Dre appears just twice in the credits for All Eyez on Me: as a producer on “Can’t C Me,” the George Clinton–assisted explosion that sets off Disc 2, and as the maestro and guest on “California Love,” a declaration of coastal superiority at a time when that felt like a declaration of war. While “California Love” officially appears on All Eyez on Me only as a remix, the famous Joe Cocker–sampling version became the album’s lead single. To this day, it’s the biggest hit in Tupac’s catalog. It also marked one of the greatest reintroductions in all of music: “Out on bail, fresh out of jail, California dreamin’ / Soon as I step on the scene, I’m hearin’ hoochies screamin’” is among the most iconic verse openings in all of rap, even before considering the real-life circumstances swirling around it.

Yet by the time “California Love” was topping the Billboard Hot 100, whispers raged that Dre had been considering leaving the label for months—perhaps before the All Eyez on Me sessions even began. (Legend has it both “Can’t C Me” and “California Love” were originally pegged as Dre solo songs before Knight persuaded him into gifting them to Pac.) Dre later told interviewers that he was tired of the energy at the studio, where he saw engineers beaten for the smallest slipups, where cooler heads never quite prevailed. “I don’t like it [at Death Row] no more,” he said. “The mentality there is you have to be mad at somebody for yourself to feel good or make a record.”

Dr. Dre was no stranger to violence—his own personal history with it, particularly against women, has been well documented. But by most accounts, the tenor around Death Row had changed by late 1995. Things felt volatile. As Stormey Ramdhan, the mother of two of Knight’s children, wrote in her memoir, the CEO became colder and more difficult to reach after Tupac arrived. “He was enabling Suge to think he was invincible,” she said. Tupac, meanwhile, was boasting more and louder than ever, stoking the flames of the Bad Boy rivalry in the press and on wax, where he claimed to have slept with Biggie’s wife, Faith Evans. He recorded what’s generally acknowledged as the most vicious diss track ever made, “Hit Em Up,” which taunted Biggie for the alleged affair, poked fun at the Bad Boy star’s weight, and threatened his children’s lives. It was explosive, which is exactly what Suge wanted Tupac to be when he recruited him. People like Nate Dogg may have thought the rapper wanted off the label as quickly as possibly, but while he was there, he was all too happy to indulge in Knight’s sadism. “Suge did not make Pac more aggressive,” Tupac associate E.D.I. Mean told Westhoff in Original Gangstas. “But the two of them together was like lighting the match to a can of gasoline.”

One of the more infamous, more instructive stories from the Tupac Death Row era took place at a December 1995 company Christmas party at Chateau Le Blanc in Beverly Hills. A record promoter with ties to Sean “Puffy” Combs named Mark Anthony Bell was there. Knight—who believed that Combs was involved in the shooting death of his friend Jake Robles (which Combs has repeatedly denied)—reportedly escorted Bell upstairs, where he was surrounded by several of Knight’s associates. Knight then reportedly asked him for the addresses of Combs and Combs’s mother, and when Bell refused, he was robbed and beaten severely. According to what Bell told investigators, Knight exited the room at one point and reemerged with a champagne flute filled with urine for Bell to drink. He says he knocked it away and tried to escape off a nearby balcony before he was pulled back in. Bell also recalled Tupac whispering in Knight’s ear several times during the incident.

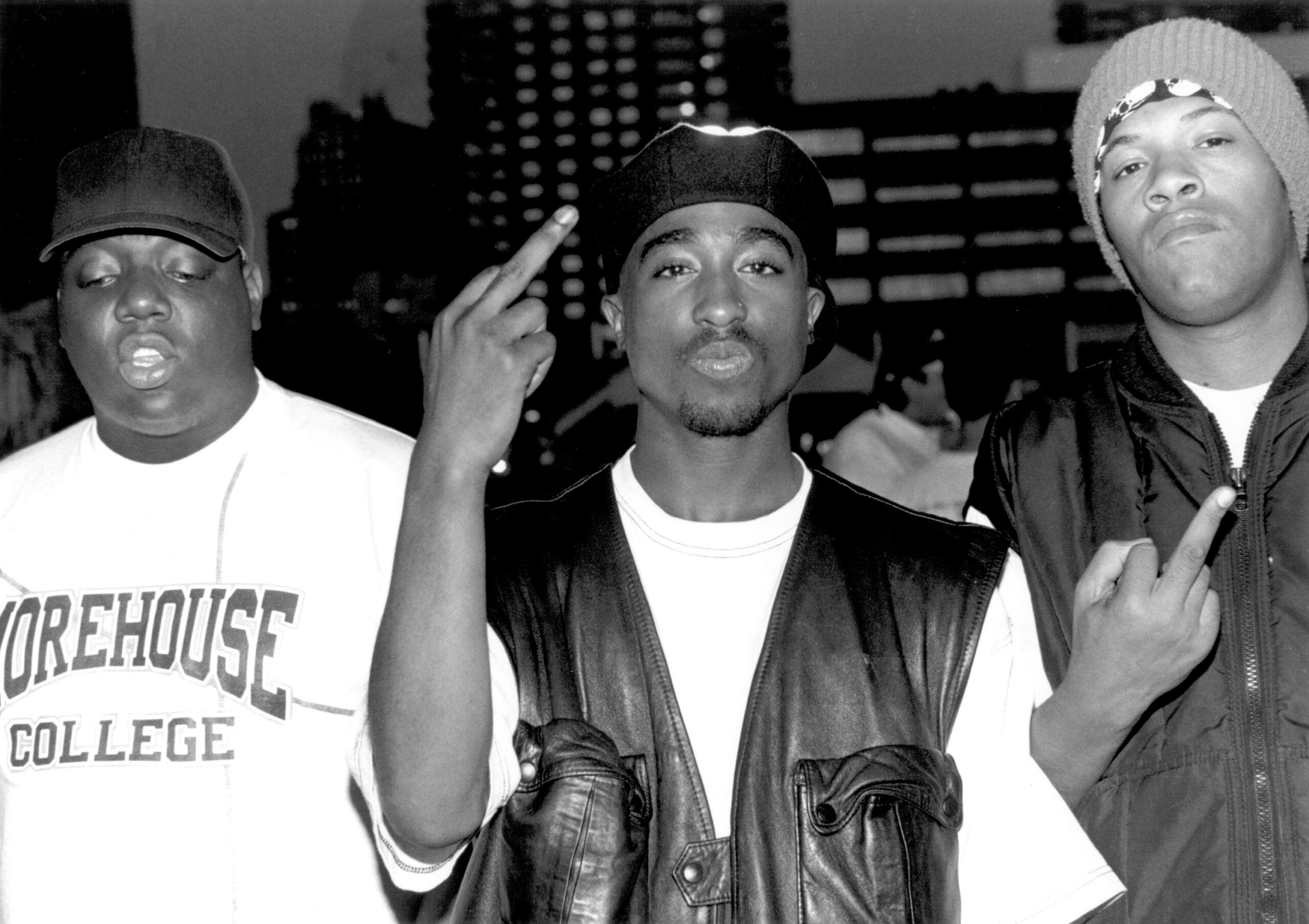

The combustible energy followed Tupac and Knight nearly everywhere they went, especially when Bad Boy Records was involved. At the March 1996 Soul Train Awards in Los Angeles, Tupac came face-to-face with Biggie for the first time since the night of the November 1994 shooting. It nearly got physical—Biggie denied reports that Tupac pulled a gun on him, but he did describe the sinister vibe to the interaction: “They made everything seem so dramatic,” he told Vibe magazine for its September 1996 issue. “I felt the darkness when he rolled up that night.” The same month that issue was published, an impassioned Pac told a reporter outside the MTV Video Music Awards that Death Row was there to overthrow Bad Boy, Nas, and any New York rapper they deemed a threat. Even in the low-definition video, you can see the veins bulging from his head.

While Tupac full-throatedly repped Death Row in public, privately he may have been thinking differently. Throughout 1996, he put more energy into his acting career, spending most of that spring and summer on the sets of Gridlock’d and Gang Related. He also plotted his own label—which, according to lawyer Charles Ogletree, would’ve been named Euphanasia—and put more focus into his crew, the Outlawz, a collection of rappers mostly from New Jersey that he had featured prominently on All Eyez on Me. “He was building something that was all to be part of one entity,” Ogletree told The New Yorker in 1997. “He had a strategy—the idea was to maintain a friendly relationship with Suge but to separate his business.”

On some level, the push-and-pull of his relationship with Knight aligned with the dualistic image of Tupac that had taken shape: the sensitive poet with “Thug Life” tattooed on stomach, the author of feminist anthems who was convicted of sexual abuse, the man who refused to pledge himself to a gang but seemed willing to risk it all for allegiance to a record label.

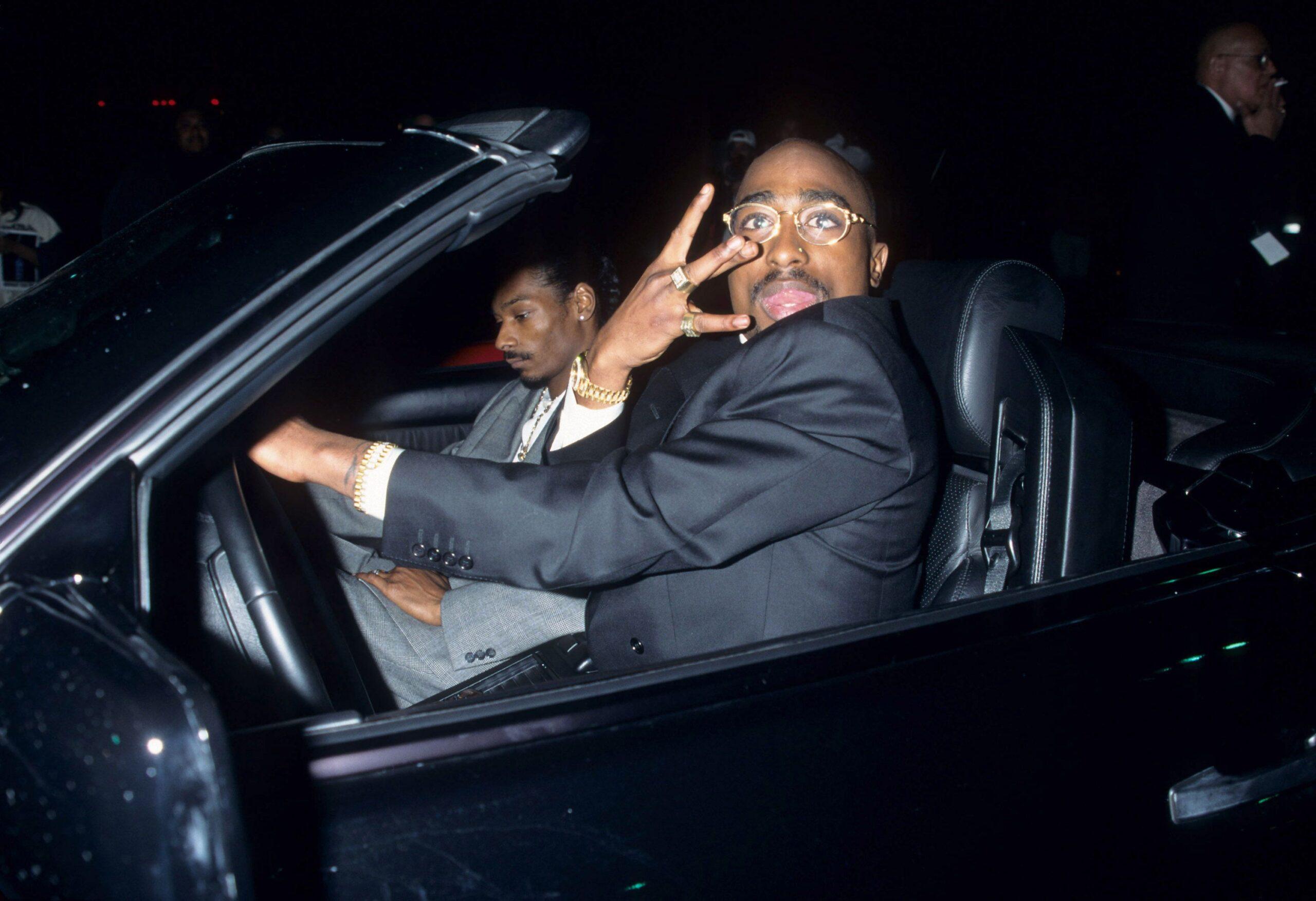

Tupac, however, would never get the chance to break out on his own. Less than a week after the VMAs, Knight invited his star to Las Vegas for the Mike Tyson–Bruce Seldon fight on September 7. Tupac at first protested, but eventually relented. Shortly after the fight, which Tyson won by knockout 1:49 into the first round, Tupac and Knight’s entourage was at the MGM Grand when someone spotted a man named Orlando Anderson, a reputed member of the Southside Crips. He had allegedly stolen a Death Row chain—featuring the famous electric-chair logo—from an associate of Knight’s, and according to Original Gangstas, Knight believed Anderson may have also had a connection to Jake Robles’s killing. Tupac approached Anderson and hit him. Soon Knight and the rest of the group piled on. The incident was caught on the casino’s security cameras.

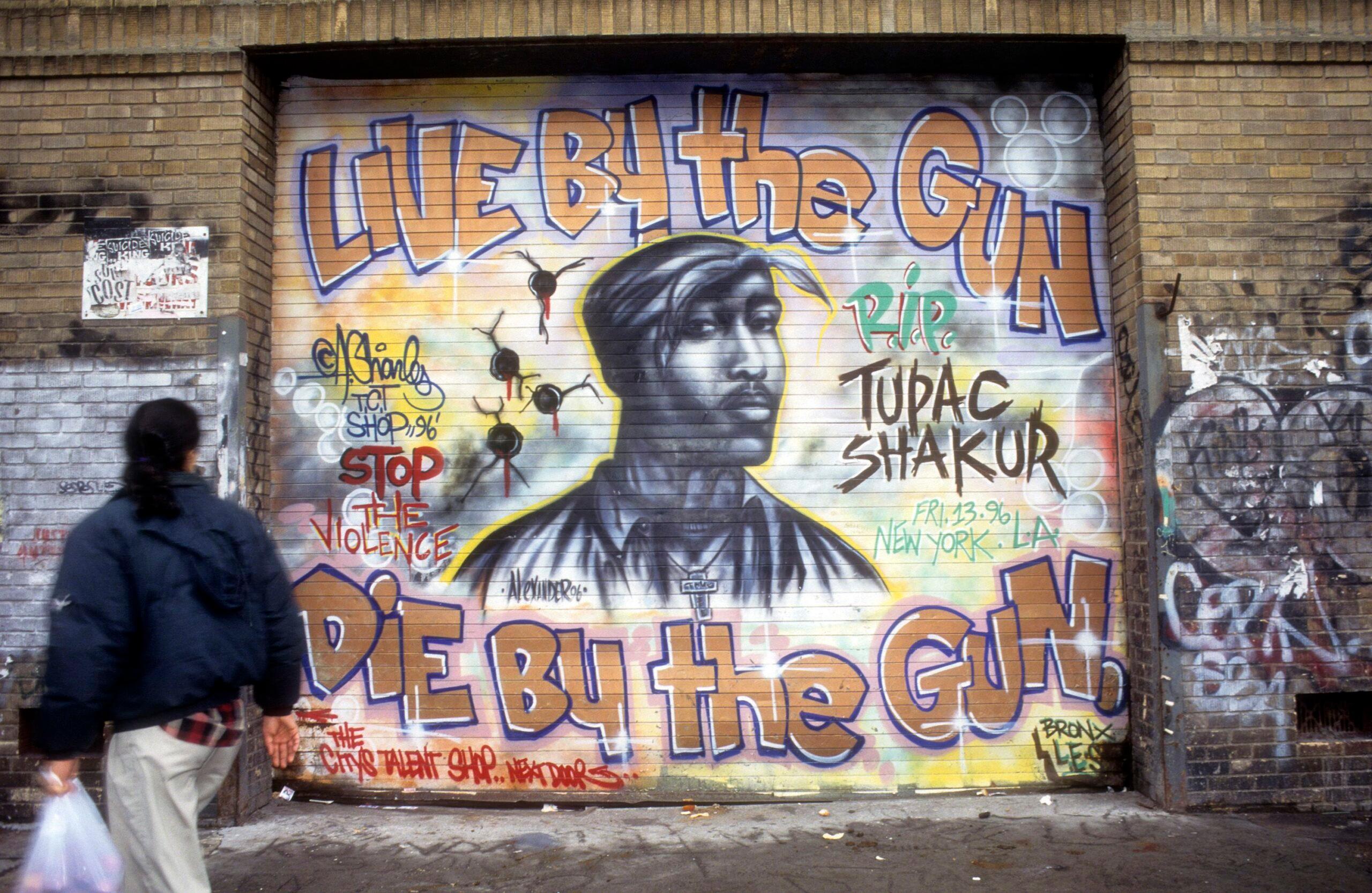

A few hours later, as Knight drove himself and Tupac to an afterparty at 662, the Vegas nightclub owned by the Death Row CEO, a white Cadillac pulled up alongside them. One of its passengers pulled out a .40 S&W Glock 22 and opened fire, striking Tupac four times. He spent the next week in University Medical Center of Southern Nevada. After going into cardiac arrest the next Friday following the removal of his right lung, doctors stopped resuscitation efforts at his mother’s insistence. Tupac Shakur was dead at age 25.

Knight, who suffered only superficial wounds in the shooting, told a reporter that he was sitting on Tupac’s bed as he passed: “He called out to me and said he loved me.”

At the end of 1996, Vibe magazine ran another story on Death Row Records. Snoop Dogg stands alone on its cover, the title “Last Man Standing” emblazoned above his head. This was true, particularly as it related to the men who had been featured 10 months earlier: Tupac was dead; Dr. Dre had signed over his stake in the label and set out to start Aftermath Entertainment, which within a few years would eclipse Death Row. And Knight’s role in the Orlando Anderson beating landed him in prison for four years for parole violation. Snoop wouldn’t stay much longer, either—his sophomore LP and last for the label, The Doggfather, came and went with a whimper that November, just months after he was acquitted of murder charges. His third album, 1998’s Da Game Is to Be Sold, Not to Be Told, would be released by another prominent artist-driven rap label: New Orleans–based No Limit Records. However, unlike Knight, No Limit’s founder Master P took great steps to keep his artists away from the real-life violence they rapped about, at one point moving his operation to the rural-by-comparison Baton Rouge.

That February 1996 Vibe cover—the one of the four pillars of the Death Row empire—is on the short list for most famous magazine images of all time. It adorns T-shirts, posters, and likely to Knight’s chagrin, rugs. That’s partly because it looks great, with credit due to both Ken Nahoum’s photography and the Vibe team’s art direction. But it also tells a story that’s become more tragic with each passing year: the most infamous record label in history at its absolute peak, just moments before the crash. And as an ever-growing number of people connected to All Eyez on Me pass away—not only Tupac and Biggie, whose killings both remain officially unsolved, but also Johnny J, Dave Aron, Nate Dogg, several members of the Outlawz, and Tupac’s mom, Afeni—the more the shadows creeping onto each man’s face seem foreboding. Some of the faces are barely recognizable now; Dr. Dre sells headphones, Snoop Dogg is best friends with Martha Stewart. Suge’s face, meanwhile, has seemingly never changed—the man we see on that magazine cover isn’t so different from the one we saw in a Los Angeles courtroom in 2018, being sentenced to 28 years in prison after running over two men (and killing one) near the set of Straight Outta Compton, a movie that depicts him as a violent enforcer.

These days, Death Row lives on only as an idea and marketing opportunity for Urban Outfitters. Drained of most of its talent by 1997, it would slink along for another decade, mostly propped up by posthumous Tupac releases culled from the prolific sessions that birthed All Eyez on Me. Without a flagship act, the label turned to stunts: Chronic 2000, a compilation of diss songs aimed at past artists, a failed rebrand as Tha Row. Meanwhile, the lawsuits poured in from all corners, most notably from Tupac’s estate, who said Knight withheld millions. Death Row would also face a racketeering probe that examined allegations it sanctioned murders and trafficked drugs; it resulted only in minor tax evasion charges. The label would declare bankruptcy in 2006, and soon after, its assets began being passed around to various entertainment companies and private equity firms. Today, Hasbro—that Hasbro, the Rhode Island toy manufacturer—owns the most famous back catalog in gangsta rap.

In January 2009, the contents of Death Row’s offices were liquidated in a warehouse in Fullerton, California, an Orange County community about 20 miles from Compton. The items included shirts, posters, paintings, and cigar cases engraved with the label’s iconic logo. The most popular piece at the auction, however, was a life-sized electric chair that Knight kept in the office—a garish representation of a label that saw $75 million in revenue in 1996 alone. The man who won it cited Tupac as his favorite Death Row artist.

The winning bid was a paltry $2,500.