The Beach Bum Who Beat Wall Street and Made Millions on GameStop

Mike McCaskill spent years scouring the stock market and betting on long shots. Then he found the opportunity that changed his life—and helped spark the mother of all short squeezes.Jim Cramer, the normally amped-up host of CNBC’s Mad Money, a stock market show complete with sound effects and wacky props and flashy graphics, looked subdued and serious during his January 14 broadcast. “I want to talk about some very important shortages that are going on in the market that you probably don’t know about,” Cramer said. He looked directly into the camera and explained a short squeeze—a concept everyone in America now seems to understand but that was still fairly obscure just a couple of weeks ago. “I don’t normally discuss these issues. … It’s a nightmare.”

Cramer described his own experience losing money in a short squeeze 30 years ago during the savings and loan crisis. His tone was concerned, quiet. “When you short a stock you are always on the hook to your broker and sometimes that blows up right in your face. And right now, it is blowing up in somebody’s face big time.”

Then Cramer ran over to his giant soundboard covered in large plastic buttons. “Shorting GameStop had been like shooting fish in a barrel!” He banged on one of the buttons. A sound effect of machine gun fire blared while Cramer grinned maniacally. “Right now an astounding 144 percent of GameStop stock shares have been sold short. That’s far more than there is! That’s not right! When you can’t find shares to borrow your broker will close out your short position. Which is how something like GameStop could tack on 27 percent … today?”

Over the next two weeks, not only would GameStop tack on 27 percent, it would watch its share price skyrocket from $38 to $483. It would become the most talked-about stock—and story—in the country. But before January 14, when Cramer told his audience about it, there were few people who had been paying attention to GameStop and the circumstances that would cause the “Mother of All Short Squeezes (#MOASS).” The ones who had would soon find their lives upended, their worlds changed, their wealth and power immense. And Wall Street would soon find itself pulling out all the stops to hold them back.

Later that day, on CNBC’s Squawk on the Street, Cramer continued to talk about the storm he saw brewing. “We know who is powerful on the street. It’s Reddit first, [Barstool Sports founder Dave] Portnoy second, I don’t know, the guy who’s got GameStop, the short squeeze third.” But who was the guy who got GameStop?

Three days after Cramer’s broadcast telling the world about the potential for a GameStop short squeeze, 45-year-old self-described “beach bum” Michael McCaskill was officiating the finals of a youth beach volleyball tournament in Louisville, Kentucky. “I know it’s Louisville, Kentucky, it sounds weird,” McCaskill says when he detects my surprise at there being beach anything in Louisville. The host venue, King Louie’s, is a sprawling sports complex with a large indoor arena and several sand volleyball courts. McCaskill runs the volleyball programs there. He says working his way up from volleyball referee to sports league director has been the only “real job” he’s held for many years. “I mean, working for my parents was a real job, but it was working for my parents. I’ve worked at some restaurants as a server when I was really young, but I’ve never had a real job. So when I started getting poor, I started refereeing.”

McCaskill once dreamed of being more than just a beach bum in a town with no beaches. He attended the University of Kentucky to study finance, but dropped out in 1994 after a semester. He then enrolled at the University of Louisville, but didn’t make it past three years. “School was never for me,” he says. “It wasn’t that I was a bad student, it was that I don’t necessarily work great, let’s say, with others.” He ended up working for his parents at their furniture store, where he was surrounded by amateur stock-pickers. “My stepfather traded stocks,” says Brian Delling, McCaskill’s younger half-brother. “Mike kind of picked up on it and ran with it.” In addition to his stepfather, one of McCaskill’s coworkers seemed to be making money on the side by investing in silver on the commodities market. McCaskill peppered him with questions, which led him to stock trading message boards and chat rooms on the internet.

On forums like RagingBull and HotStockMarket.com, he learned the ins and outs of a strange corner of the financial sector: the over-the-counter market. This is where distressed companies are traded in a decentralized market without any disclosure requirements. Shares of companies traded on the OTC markets are commonly referred to as “penny stocks,” but the truth is some companies have shares that trade for fractions of even that. “A stock could trade down to as little as a hundredth of a cent. At a hundredth of a cent, you can buy a million shares of stock for a hundred dollars,” McCaskill says. “It’s a wild, generally unregulated type of industry that’s just a free-for-all. And in the early 2000s, it was a complete free-for-all.”

After teaching himself how to trade penny stocks, McCaskill found a company that he thought looked like a good play. The ticker symbol was QBID, which stood for Q Television, a company that hoped to create the first LGBTQ television network. In 2005, the stock was trading at a hundredth of a cent. But McCaskill saw there was a serious PR effort behind this company’s plan. At such a small price, he figured, why not take a chance? He bought 3 million shares. “Well, the PR machine kept rolling and that stock ended up making the nuts at three cents, and that three cents, that turned into $90,000,” he says. “And I was, I don’t know, 25? I thought I was going to rule the world after I hit that.” McCaskill went out partying with his friends to celebrate his big score. When he returned, he checked the stock, and it had ticked back down to a penny. “So I didn’t make my big 90,000, but I still made 30.”

“Well, the PR machine kept rolling and that stock ended up making the nuts at three cents, and that three cents, that turned into $90,000. And I was, I don’t know, 25? I thought I was going to rule the world after I hit that.” — Mike McCaskill

In 2007, the family furniture store fell into bankruptcy and closed, and McCaskill was left without any day job to fall back on. He decided he could turn his stock-picking hobby into his full-time gig. He sold his car and bought an inexpensive truck, then put the balance of the money—around $10,000—into his trading account. Within a year he had built it to $160,000 by trading penny stocks. Roy Kortick, a visual artist who was living in a Brooklyn loft and trading penny stocks on the side, befriended McCaskill during this time. They both posted regularly on the same stock message boards. “We were drawn to similar types of situations. I could tell he was a trustworthy person,” Kortick says. In addition to sharing similar progressive worldviews, the two had an eye for the same kinds of companies to invest in, and they shared stock plays with each other. “He’s really great at spotting, at building momentum.”

McCaskill also developed a keen eye for identifying red flags when researching a company—a skill that was essential in the OTC markets, which were rife with fraud, financial crimes, and all sorts of outright shenanigans. “I mean, it’s a shady world,” McCaskill says. “I can look at something very quick and I can tell you if it’s a scam.”

By 2007, McCaskill’s Spidey sense was tingling in a big way. Something was amiss in the OTC markets. “The penny market just stopped and people were pulling liquidity out of the market. … And then along came 2008.” The financial crisis wiped out a lot of big players on Wall Street, but McCaskill says one aspect of it caught his attention. The volatility caused by the crash got him interested in “big board” stocks, the stocks listed on the New York Stock Exchange, for the first time in his life. “If something dies down to $5 that was $20 and it’s going to bounce back up, that’s the things I get interested in,” he says.

McCaskill saw opportunity in the chaos, but to profit from it he would have to develop new skills. “Even though I had no idea almost what I was doing,” he says, “talk about the time of your life to learn how to trade options.”

Options are a way to trade stocks with a smaller risk relative to the potentially high reward. Essentially, they are contracts to buy (call) or sell (put) a stock at a certain price during a fixed period of time. They are complicated, but the gist is that instead of buying a share of a stock for, say, $100, you buy a call option that allows you to buy a share of that stock for $100 at a later date. If the price of the stock goes up, you still get it at the discounted price of $100 no matter how high it climbs. If the price goes down, you don’t have to exercise your option, and can throw the contract away and pay a predetermined premium. Options are about timing the market and calculating probabilities. A trader like McCaskill, who had made his bones monitoring some of the most volatile stocks available through the OTC markets, seemed to be well-primed for the newly volatile stocks on the major exchanges.

He figured his ability to find real financial red flags would prove useful. After all, as the 2008 financial crisis ripped through the economy, fraud was being exposed everywhere he looked, even in the unlikeliest of places. Some of the most venerated financial institutions in the United States—Bank of America, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers—were crumbling beneath the weight of the housing fallout. “When you’re sitting there trading in it and it’s absolute carnage, there’s a reason why they’re going under,” McCaskill says. “You know that there is. So you become pretty pessimistic and negative.”

But McCaskill’s foray into the big board stocks wasn’t met with the same early success he found in penny stocks. There was a steep learning curve. “I remember making $60,000 one day and not being aware that my puts expired the next day,” he says. “And the next day it was all gone.”

“I remember making $60,000 one day and not being aware that my puts expired the next day. And the next day it was all gone.” — McCaskill

McCaskill saw huge fluctuations in his trading account during this period. He was betting short-term options—options that expired within one week—on extremely volatile stocks, essentially risking as little as possible to try to hit a long shot and make a bundle. “It’s more than likely, 95 times out of 100, it’s not going to work,” he says. “I’m betting on that one time out of 100 that it’s going to work.” McCaskill knew that if he kept betting on huge long shots, his day would eventually come. He just needed that day to come before he went broke.

As the government tried to figure out how to save the American economy from collapse, McCaskill made bets that the newly elected Obama administration would be good for the market. He figured that things were already at rock bottom and had nowhere to go but up. And America was swollen with optimism and enthusiasm about the new president. But it turned out that the economy had a little bit further to slide. “I remember Bank of America just almost going under right when January started and it’s like, ‘Oh, you got to be kidding me.’”

He got wiped out. “I mean, zero, my account was zero.”

McCaskill grew cynical after that experience, and set out to uncover which domino would fall next. He switched from betting on the Obama administration’s success to betting on its failure. And then the bailouts came. In early 2009, the federal government began to buy back many of the toxic assets financial institutions had on their books in order to save them from failure and to encourage them to start lending money again. In all, the government spent $700 billion. The program was met with anger and skepticism by many Americans, including McCaskill, who structured his investments in anticipation of stocks continuing to decline. “At that time, very few people understood how well [the bailout] would work,” he says. The infusion of cash into the big players on Wall Street lubricated the markets and got stocks moving up again—once again wiping McCaskill’s accounts clean. Every which way he turned, he was getting killed. He could not seem to make sense of the madness happening in the markets. So he took a break. He went to play some volleyball. And he figured out how to scrape together a living on the courts.

For the next decade McCaskill would live the life of a beach bum, and every time he’d scrape together an extra $500 he’d stick it in his investment account and swing for the fences. “Like, let’s find the 100-to-1 shot,” he says. “Once in a while you really hit one good and then you try to do it again. You try to parlay it. Yeah, and then that never worked.”

“Like, let’s find the 100-to-1 shot. Once in a while you really hit one good and then you try to do it again. You try to parlay it. Yeah, and then that never worked.” — McCaskill

None of McCaskill’s moonshots landed, but he never stopped paying attention to the markets. One day in 2019, an old friend from his penny stock days reached out to him with a tip. The ticker symbol was SOLI, for a company named Solei Systems. It was a “gray sheet” stock, meaning the Securities and Exchange Commission had suspended it from official trading for one reason or another. But when McCaskill looked at it, he saw someone building an interesting telehealth company in the shell of this failed venture. Intrigued, he bought 700,000 shares. “I bought it pretty heavily for the amount of money that I had at that time.” The stock rose from a penny to five cents. McCaskill got excited and started telling his friends and family about the stock. And the price kept going up. He was finally doing it. And his friends and family were along for the ride. “We were surprised, it was kind of the find of a lifetime,” he says.

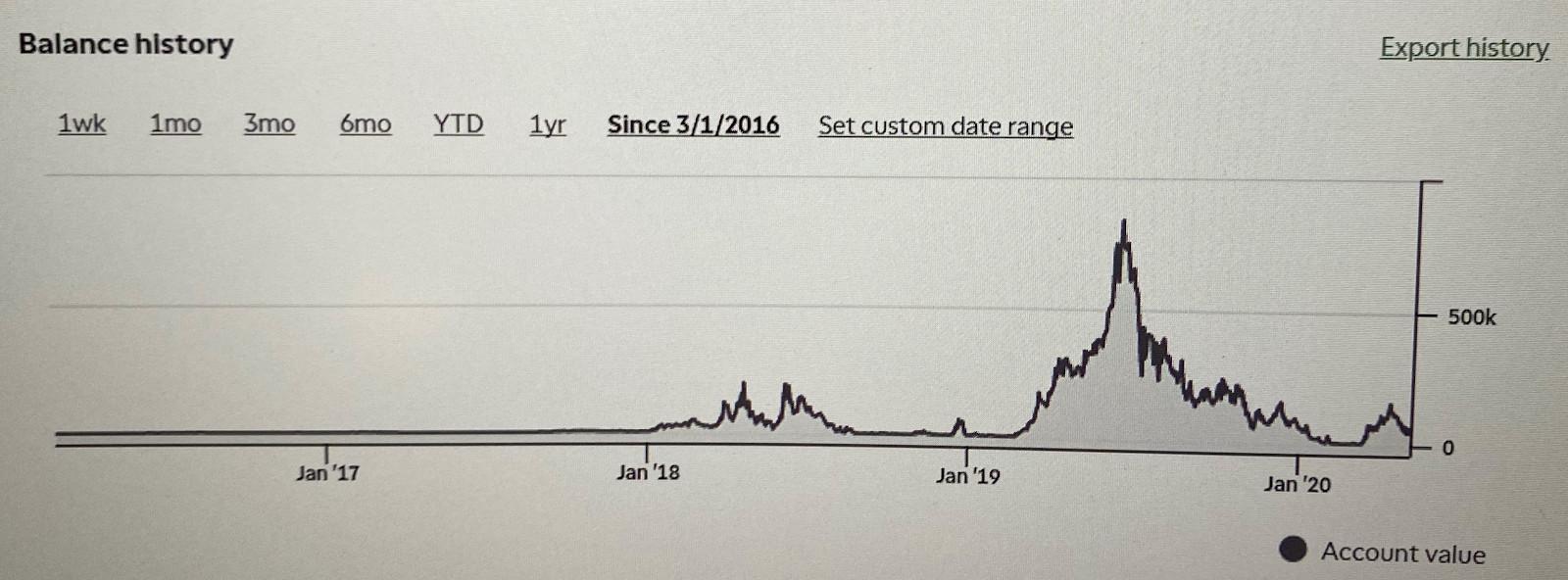

Over the next eight months, the stock went all the way up to $1.30 a share. “And the big dream for a grinder, I’ll say like me, was always to get your bank account to a million dollars,” he says. “I got right up to that $955,000. I remember, I got a picture of it. I’m up to 955, I’m almost to my million, I’m doing my dance. I’m like, ‘I’ve done it, hi-ya!’

“Then it crashes back down.”

The stock plummeted all the way to 20 cents. “We’ve always told him, just get out you’ve made some money,” says Ken Hayden, McCaskill’s uncle who worked as an account manager at UPS in Louisville. “But Mikey has always strived for a larger hit. He’d have done a lot better over time if he didn’t hold on to things as long as he had.” Kortick echoes that sentiment. “Mike was more of a gambler,” he says. “I’ve seen him blow up a few accounts.”

McCaskill wasn’t ready to let his fortune flutter away. He started buying options to try to make back the money, but those failed, and he busted again. “I was like, ‘Man, no more pennies.’” Determined to get his mojo back and capture the riches that eluded him, he rolled up his sleeves and turned to trading options on the big board stocks.

The volatility that originally drew him into trading options back in 2008 wasn’t there to the same extent in 2019. But that isn’t to say there wasn’t any. McCaskill knew that the right kind of stock for the right kind of trade—low investment, high reward—was out there. So he scavenged. And he found a website called highshortinterest.com that kept a daily updated list of stocks that had high short interest.

Short selling happens when someone thinks a stock’s price will go down, and they borrow a number of shares from a lender for a set period and agree to return it with an interest payment later. Short interest is the percentage of a company’s shares that are loaned out to short sellers but haven’t yet been returned. If a company has high short interest, that means there are so many shares loaned out to short sellers that it’s hard to find shares on the open market to buy and return to the original owners. In these situations, one of two things can happen. If there’s no interest in buying the stock, the price will continue to go down, and the short sellers will clean up. If there is a sudden demand for shares, however, the limited supply of shares not already loaned out to short sellers can cause the price to quickly skyrocket. “Those stocks if they get the right news can go way up, or if they get even worse news, they can go way down,” McCaskill says. “They’ve got great volatility.”

McCaskill was looking for a company that had an abnormally high short interest percentage, perhaps with 50 or 60 percent of its shares being sold short. The company at the top of the list he found was a strip-mall video game retail chain called GameStop—yes, the one widely known for haggling with gamers over the price of their used copies of Mario Kart. GameStop’s short interest was an astounding 90 percent. That got McCaskill’s attention. He wanted to know why the number was so high, so he did some research.

What he discovered was that GameStop traded around $20 in 2018, before the shorting began. The company was in bad shape, sure, but that was mostly because the retail landscape was changing—not just for GameStop but for everybody. Still, a short interest of 90 percent suggested that the market believed this company was literally going out of business, and McCaskill just didn’t see it that way. GameStop was slimming down. It had money, so it wasn’t on the brink of bankruptcy. And it was going to generate revenue when new video-game consoles like the PlayStation 5 came out in 2020. But the hedge funds shorting GameStop compared the business to Sears or K-Mart. Barron’s put GameStop on a list of “‘Radio Shack’ Stocks.” “GME is the Blockbuster of video games,” wrote Brett Owens at Forbes in 2019, “and it’s at real risk of running out of lives as gamers go online to get their fix.” The near-consensus was this business was on its way to pasture. The stock was shorted down to $5 a share.

One person who wasn’t shorting GameStop back in 2019 was the investor Michael Burry, who was famously portrayed by Christian Bale in the film The Big Short. Burry’s fund, Scion Asset Management, owned 3 million shares of GameStop, about 3 percent of the company. In an effort to revive the stock price, Burry wrote a letter to management in August 2019 calling for it to spend some of GameStop’s cash on hand to buy back existing stock “at once and with urgency.” Burry argued that “such a repurchase would increase earnings per share dramatically—far more than any other possible action on a per share basis.” Management listened, and by December had spent about $178 million buying back about a third of the outstanding shares. Then management “retired” those shares, thereby decreasing the number available on the market. Ordinarily, a move like this would push the price of the stock higher. If a company like Apple bought back a third of its shares, the price would go through the roof. But nothing happened. The price didn’t budge. And the short percentage grew even higher.

“So when I’m researching this on why the company ended up on the high short interest list, it’s because these maniacs, this hedge fund or group of hedge funds, literally shorted everything that GameStop bought back,” McCaskill says. “I was fascinated because I’ve never seen anything so boldly stupid in my life if a company’s not going to go under.”

These maniacs, this hedge fund or group of hedge funds, literally shorted everything that GameStop bought back. I was fascinated because I’ve never seen anything so boldly stupid in my life if a company’s not going to go under.McCaskill

McCaskill realized that GameStop presented a rare opportunity. After the stock buybacks, the bet was simple: You either believed GameStop would stay solvent or thought it would go out of business. If it went out of business, the shorts would make a killing. If it managed to stay afloat, the price had virtually nowhere to go but up. And now that there were even fewer shares on the market, the short interest raised to an eye-popping 110 percent.

Now you may be wondering how that’s possible. How can there be a short interest of 110 percent? How can there be 110 percent of anything? “Basically all the stock got borrowed up,” says Tom Gladd, a retired quantitative analyst who has worked for Citi and Morgan Stanley. “That would be 100 percent of the stock being shorted. Those people would then sell the stock in the market to other people, who were then long in the stock and they could loan it out. So the same stock gets loaned out more than once.”

This means that short sellers were borrowing GameStop stock from shareholders (probably from those shareholders’ brokers, without the shareholders’ knowledge) and then immediately selling the stock into the open market, with the intention of buying the shares back later at a lower price. However, the people they sold the shares to were also short sellers, who also intended to sell the shares into the open market and buy them back later. It’s like holding up a mirror to a mirror, an M.C. Escher drawing of a stock trade. The fact that it’s all legal simply beggars belief.

But it was legal, unlike “naked short selling,” which is against the law. Naked short selling is when you sell shares that you can’t confirm actually exist—essentially selling a promise you’ll get the shares from … someone. According to Sammy Azzouz, president of Heritage Financial Services and author of Beyond the Basics: Maximizing, Allocating, and Protecting Your Capital, this used to be fairly common. “The SEC banned the practice in 2008 as a result of the financial crisis and run on financial-related stocks that some say sharpened the market turmoil,” Azzouz says. “The problem is that naked short selling can cause the short bet against a company to be larger than the shares available in the market. It facilitates manipulation in stock prices since the short bet is not connected to the amount of shares available.”

If this sounds a lot like what was happening to GameStop, well, that’s because it is. To the SEC, though, there’s a distinction between selling a share you don’t own and selling the same share over and over. “The rules have some loopholes,” Azzouz says.

“It’s a fabricated share, is the best thing that I can say,” McCaskill says of what he saw in the GameStop stock short interest. “I’ve asked a lot of people this question, I was like, ‘How can people continue to short? If there are no true shares trading, how did that happen?’ And it’s because shorts are built on top of shorts, on top of shorts, on top of shorts. It’s like a pyramid scheme. It’s like, ‘Oh, I’ll short these, I’ll loan them out, I’ll buy these.’ And it never ends. It’s like a never-ending cycle.”

McCaskill endlessly studied GameStop. He learned about its fundamentals. What he saw wasn’t a company trying to die. He saw a company with real fight in it to live. And he believed that there was a trade to make. A big one. “I knew that one day this would explode,” he says.

He started buying 1,000 call option contracts on GameStop every week, which meant that he was willing to pay a small premium on each contract in exchange for the right to buy the shares at the current prices if the stock price managed to go up within the week. “The contracts were maybe five, 10 cents. And I’d buy an assload of them,” he says. “And they would expire worthless every time, because the shorts sat on that stock. No matter what happened, it didn’t matter. They were defending that like it didn’t matter. And I lost my ass on calls, over and over.”

“I was like, ‘How can people continue to short? If there are no true shares trading, how did that happen?’ And it’s because shorts are built on top of shorts, on top of shorts, on top of shorts. It’s like a pyramid scheme.” — McCaskill

McCaskill wondered why the hedge funds that had shorted the stock weren’t covering their shorts. Surely, he thought, they would buy back the stock when it was below $4 and return it to wherever they borrowed it from. At some point, the shorts would have to cover. And when they did, the demand for the stock would tick the price back up. But it never happened. And then it occurred to McCaskill—the funds weren’t ever going to cover their short positions, because they couldn’t. They were trapped in what he calls “an irreversible trade.” Unless GameStop issued new shares, those who shorted the stock were running out of places to buy shares that they hadn’t already bought and sold. “They made it to where there are no real shares,” McCaskill says. “They were betting that this was going bankrupt and that it would never survive. And it was an interesting bet, but it was wrong.”

As McCaskill continued to lose money trying to time his options to an uptick that never came, he touted the stock to all of his friends and family once again. He convinced his uncle Ken, who was at this point had retired from UPS, to invest. “He’s always teased me because I’m pretty much still holding a significant share in UPS,” Hayden says. “He says, ‘You can’t make money on that old bear.’” But Hayden trusted McCaskill. He remembered the money they had made in SOLI. And he knew how hard McCaskill worked. “The guy gets up at 3 in the morning, way before most people, and he’s online most of the day,” Hayden says. “He’s not a goofball. He knows his shit.” Hayden bought about 6,000 shares.

McCaskill’s brother took more convincing. “I’m pretty risk-averse most of the time. I don’t really try to play these things,” Delling says. “He was always chasing the white whale. I’ve always told him, ‘Mike, you’ve been Captain Ahab for a long time. It’s time to stop chasing the white whale.’”

McCaskill really did seem to think GameStop was his white whale. And he would suffer like Ahab in pursuit of it. At that time, he believed it might triple or quadruple in value, so he invested in options that would pay him off exponentially higher rates of return. “To me, you’ve got to time this short squeeze because this thing could go to $50 and rip somebody’s head off,” he says.

What McCaskill was waiting for—the short squeeze—was the moment when demand in the stock would outpace the supply not already being shorted. When that happened, the price would go up so much that the owners of the stock that had been loaned out to short sellers would call back in their shares. Those short sellers, who had already sold the stock in the hope that they could buy it back cheaper, would be forced to go find whatever stock they could, thereby creating more demand and inflating the price even more. The result would be a rapidly accelerating price (“to the moon!”). But the day never seemed to come. All through 2020, McCaskill banged his head against the wall buying short-term options, hoping for the short squeeze to begin. “It had maybe a 20 or 30 percent pop, and maybe I made a little money, but believe me, I lost it the next day trying to do it again.” Looking back, he says his strategy was “moronic.” Then, while searching for somebody, anybody, who was seeing what he saw in GameStop, he discovered Roaring Kitty’s YouTube channel.

Roaring Kitty is 34-year-old Keith Gill, who, unbeknownst to McCaskill or anyone else, was also posting on the popular Reddit sub r/WallStreetBets as “DeepFuckingValue.” Gill was trying to play GameStop options in 2019. By July 2020, Gill had started a YouTube channel on which he’d livestream himself talking about his stock plays and investing strategies. On July 27, when GameStop was still at about $4 a share, he made an hour-long video laying out his case for why the company was a good investment, and inviting viewers to help him figure out whether the assumptions he was making were wrong.

When McCaskill discovered Gill’s channel, it was a revelation. Finally, someone else was talking about what McCaskill saw in the stock. But even though McCaskill was looking for validation in his thesis, he remained skeptical of the source. Gill wore loud, colorful clothing and spoke in the parlance of memes. He seemed to be broadcasting from his basement. “He was kind of crazy,” McCaskill says. “Sat there and talked about GameStop for four hours.” Still, everything Gill said tracked with McCaskill’s thinking. McCaskill watched the videos and chatted with Gill, and soon he realized what Gill was doing differently—he was buying options that expired in months instead of a week. Those options cost more than McCaskill’s options, but they gave GameStop a longer horizon to make its move. “He bought himself time,” McCaskill says.

McCaskill’s strategy had been to buy the cheapest options—sometimes ones that cost mere pennies—so he could purchase high volumes of them and make the biggest payoff if they hit. The problem was that in order for his big bets to work, the stock needed to soar quickly; an improbable, but not impossible, scenario. “I’m doing that, especially with GameStop, because I know that if one slice of news comes out that’s right, it would go insane,” McCaskill says of how he was operating. After watching Gill’s videos, he switched it up and shelled out more money for options that expired farther out. And then he sat back and waited for that one slice of news to come out. He didn’t have to wait long.

In August 2020, Ryan Cohen, the founder of Chewy.com, was forced to file an SEC report because he had purchased so many shares of GameStop that he owned 10 percent of the company, making him subject to insider status. This was monumental news. Cohen, whose company was purchased by PetSmart in 2017 for $3.35 billion, was a respected leader in the tech industry. Cohen was an expert in e-commerce, and his interest in GameStop seemed to indicate that he believed he could help the company transition to online sales.

But more than all that, Cohen’s purchase of what amounted to 9 million shares of GameStop signaled that he saw the stock as being a valuable investment. After all, only a couple of months before the disclosure, Cohen had made waves on Wall Street when he announced that he was investing the entirety of his fortune into only two stocks: Apple and Wells Fargo. GameStop was joining an elite and exclusive portfolio.

This was the break that McCaskill, Gill, Burry, and others needed to get the stock moving up. The short sellers had been able to keep the price low time and time again, backing up their positions with more shorts and keeping the bad news about GameStop flowing. If McCaskill was right, the shorts were now all out of ammo, and they were cornered.

Slowly but surely, the stock started to move. In the next two months GameStop went from $4 to $10. But then the stock stalled. By November, Cohen was publicly feuding with GameStop CEO George Sherman over the company’s direction. Cohen wanted GameStop to dump real estate assets and transition to e-commerce to become the Amazon of gaming. Cohen pushed for multiple seats on the board of directors, even though nobody had any clue who could even participate in a shareholder vote. The ridiculous level of short interest meant that most of GameStop’s shares were tied up in some kind of confusing and ambiguous state of ownership.

The battle between Cohen and Sherman continued through the holidays, culminating in a January 11 announcement that Cohen and two allies would be put on the board, giving him a majority and effective control of the company. “They put that press release out and I’m like, hallelujah, this is probably it,” McCaskill says. “I’m not screwing around anymore. I’m not going to miss this. I don’t give a shit.”

McCaskill loaded up. He tipped off his uncle as well. “I bought 4,000 more [shares],” Hayden says. When he called his broker to tell him how much GameStop stock he wanted to buy, Hayden says his broker “thought I was nuts.”

“They put that press release out and I’m like, hallelujah, this is probably it. I’m not screwing around anymore. I’m not going to miss this. I don’t give a shit.” — McCaskill

The stock began to climb. It crept just shy of $20 by the closing bell on January 12. Frustrated by the pace, McCaskill logged on to Twitter early the next morning and noticed that Jim Cramer was up and tweeting. “I don’t really watch Cramer, but, you know, I’m smart enough to know he’s got a large audience,” McCaskill says. “All we need is some attention here and he has already commented negatively on it. He would do ‘Sell sell sell’ and ‘That’s brick and mortar! It’s garbage!’ and I’m like, you know, I’m going to ask him a question.”

McCaskill tweeted a screenshot of the high short interest stocks, showing GameStop at the top of the list with what had ballooned to an absurd 136 percent short interest, along with a breakdown of all of the shares, the short interest, and the market capitalization.

Ten minutes later Cramer quote tweeted McCaskill. “Excuse my ignorance: where did you get this list.. kind of interesting for me to focus on. thank you for bringing it to my attention.” The next morning, Cramer was on Squawk on the Street saying that “the guy who’s got GameStop” was likely one of the most powerful people on Wall Street. And later that afternoon Cramer did a deep dive on GameStop on his show. By the end of the day, the stock was trading at just under $40 a share. “I remember talking to my wife, you know, this is the point where people are going to pressure you to sell,” he says. “Like, ‘Oh my God, you’re up? How much? And you’re not selling? Are you nuts?’ And I’m like, ‘No, you don’t understand.’”

McCaskill didn’t want to sell. He believed in his thesis that the shorts were stuck and that the stock would keep going up. He felt confident that $40 was just the beginning, as confident as he’d ever been about anything. He could feel that he was on the verge of something major. He already had a sizable position, but he wanted more on the off chance that the stock made a really big move. On January 19, he made one more trade—the biggest of his life. He bought 750 short-term $60 call options. “He was willing to lose it all in order to take that chance to hit those way-out-of-the-money options,” Kortick says. “You only need it once. One play like that and you’re done. That’s everything.”

By January 25, GameStop was trading at nearly $80 a share. Nobody could deny the mother of all short squeezes was real anymore. It was here. One hedge fund that had heavily shorted the stock, Melvin Capital, was forced to close out of its position at a massive loss, and reportedly needed an infusion of nearly $3 billion from other hedge funds, including $750 million from Mets owner Steve Cohen’s Point72. As shorts scrambled to buy more shares to cover their positions, the price of GameStop continued to soar. McCaskill’s friends and family were going nuts. They blew up his phone with texts and phone calls. Should we sell? McCaskill knew once the stock hit $40 that the infinite short squeeze was in play. He told every person he knew and loved, at great risk to his reputation and relationships, “Hold on, you haven’t seen anything yet.”

“He was willing to lose it all in order to take that chance to hit those way-out-of-the-money options. You only need it once. One play like that and you’re done. That’s everything.” — Kortick

“To be honest it was the most stress I’ve ever felt in my entire life,” says Delling, who finally decided to invest in GameStop once it hit $40 a share. “My brother is better with the stress because he has weathered the storm. I have a new family so I had to take whatever I could get for my kids and my family and the pandemic, and I didn’t want to be stupid. You get news that it’s climbing and you watch the ticker and you’re like, ‘God, how high can this thing go?’ My whole body was the sweatiest I’ve ever been sitting still.”

After January 26, when the billionaire Tesla CEO Elon Musk tweeted out a single word, “Gamestonk!!” the stock took off to an absolutely mind-melting $347 a share.

McCaskill exited most of his position. Like the song says, you gotta know when to walk away. Despite still believing in GameStop’s value, and believing that we haven’t seen the end of the infinite squeeze, he simply couldn’t justify keeping that much money tied up in the trade. After all, $25 million is a lot of money for a beach bum to manage. His brother, uncle, and Kortick all sold and took profits. The two accounts McCaskill set up for his children, ages 4 and 6, with their Christmas money netted $1.5 million each.

“It’s a Cinderella story. Mike truly is Cinderella,” Hayden says. “The money Mike made was stupid money. But it didn’t happen to him overnight. He saw this and we were in it long before all this frenzy. But now he’s set for life.”

McCaskill held on to about 2,500 shares of GameStop, because he wanted to be able to say he sold at $1,000. While selling the stock when he did was somewhat controversial among the Redditors of WallStreetBets, since many of them believed that the stock could climb much higher if those with long positions waited out the short sellers, McCaskill wasn’t looking to wage any crypto-political war with Wall Street. “I’m not part of this Reddit movement, nor have I ever been,” he says. McCaskill felt that most of the investors who had already made money in GameStop should have gone ahead and sold, particularly if the money could have made a difference in their lives. “When you start getting huge gains you have to take money off at some point.” Michael Burry took to his rarely used Twitter account to express support for those like McCaskill who chose to take their profits. “Hey, $GME is now a $stonk and may go >$1000, but if I made a life-altering amount in this stock, I’d punch out.”

“You get news that it’s climbing and you watch the ticker and you’re like, ‘God, how high can this thing go?’ My whole body was the sweatiest I’ve ever been sitting still.” — Brian Delling

Kortick had also invested in GameStop early on, but he sold around $160, making himself a fraction of what McCaskill made by holding on. “I was kicking myself, but then again I made the most I’ve ever made on a stock, so I couldn’t be that unhappy,” he says. Delling, meanwhile, sold his stake in GameStop the day Musk tweeted “Gamestonk!!” because he feared that the SEC would take action against Musk for the tweet, as it had in 2018 over tweets Musk made about Tesla. “I wish I had waited one more day,” Delling says. “I’m not one to normally praise my brother, but I’m super proud of Mike. I’ve told him that at least 12 times since I’ve sold out. I’ve told him thank you so much.

“He obviously finally got the white whale. I mean, even Ahab didn’t do that.”

In the days since McCaskill got (mostly) out of GameStop, Wall Street has pulled out every stop to push the price of the stock back down. From the popular trading app Robinhood drawing on lines of credit to stay afloat to a number of brokerages restricting the purchase of shares of GameStop, troubling signs abounded. This effort appears to be working. By the closing bell on February 2, GameStop’s stock price had dropped to $90 a share. By February 12, the stock was all the way down to $52.40. “The government will be slow to react to this, but once it does it could have serious implications,” says Gladd. “I’m almost certain the people who will get hurt are the people coming late to the game, reading the newspaper today and thinking, ‘Oh these guys got rich, I’ll max out my credit card.’ It’s the classic thing where you sell to a greater fool. These people just now coming into it are the greater fools.”

Still, McCaskill believes in the stock. He tweeted last week that he expects the squeeze to continue and that the shorts “will pay the same as they did from $4.” Burry also seems to think that trouble may still lie ahead for those who are shorting the stock. Earlier in February, Burry warned investors that back in May 2020, when he tried to call in his GameStop shares, it took his broker weeks to find the shares. “‘I cannot even imagine the shitstorm in settlement now. They may have to extend delivery timelines,’” he tweeted.

“It’s a Cinderella story. Mike truly is Cinderella. The money Mike made was stupid money. But it didn’t happen to him overnight. He saw this and we were in it long before all this frenzy. But now he’s set for life.” — Ken Hayden

As the GameStop saga drags on, it’s worth noting that the mother of all short squeezes isn’t a cataclysmic event. It’s a sideshow. While McCaskill and Roaring Kitty made millions, and Burry and Cohen made billions, most of the everyday GameStop investors who got in on the craze probably didn’t see their lives change dramatically. Maybe they bought too high and sold too low and lost a big chunk of what they deposited in their Robinhood account. Maybe they sold at precisely the right time and quadrupled their investment. Either way, they likely headed back to work Monday morning.

And for all that is made of the retail investors supposedly taking down Wall Street, the massive power of the stock market still weighs heavily on our backs. The hedge funds will keep hedging. The rich will stay rich. Meanwhile, GameStop is still a Fortune 500 company with over 50,000 employees, many of whom earn around $10 an hour. Of its 5,500 stores, it plans to close more than 1,000 by March, and many of those employees will lose their jobs. All of this will happen regardless of whether GameStop’s stock is worth $5 or $500. It’s ironic how those on both sides of the GameStop bet want the same thing: for more stores to close, either as a sign that the company is failing or modernizing. This is the paradox of the “real” economy and the casino where gamblers bet on it. They hold their mirrors up to one another. They beggar belief.

“He obviously finally got the white whale. I mean, even Ahab didn’t do that.” — Delling

As I talked to McCaskill at the end of January, GameStop was at $325 a share, the whole world was obsessed with it, and his cup was about to runneth over. Yet the next day he planned to run a volleyball tournament at King Louie’s for $700. Here, too, was a paradox. McCaskill had no intention of letting his newfound fortune change him. If anything, the money afforded him the privilege to continue being exactly the same person he has always been. “I’m not going to go buy the Lambo and act like an imbecile,” he says. “I’m pretty minimalist. It’s more of just the satisfaction of, I did that.”

Despite catching his white whale, the guy who got GameStop is still a Wall Street player without a college degree. A beach bum in a town with no beach.

David Hill’s book, The Vapors: A Southern Family, the New York Mob, and the Rise and Fall of Hot Springs, America’s Forgotten Capital of Vice, is out now. His website is davidhillonline.com.