Although the record books of baseball are staunchly anti-asterisk, we can add our own imaginary asterisks to almost every aspect of the 2020 MLB season. Player seasons, certainly: We’ll never know whether a given player’s 2020 stats reflect what he would have accomplished over 162 games or whether he happened to cram his coldest or hottest stretch of the year into the 60-game season. Award wins, postseason appearances, statistical baselines: All were subject to the vagaries of a pandemic-disrupted season that started in late July and adopted a different set of rules, schedule, roster size, and playoff format than any other year. There’s just one thing about the 2020 season that doesn’t deserve any doubt: the team that won the World Series.

It wasn’t ideal that the Dodgers broke their decades-long drought between championships in a year when their march to the title was curtailed, when (almost) no fans were in attendance, and when Justin Turner sullied some of the good Game 6 vibes by returning to the field and removing his mask after a positive COVID test. But the Dodgers’ win was as legitimate as any other champion’s. If anything, they had it harder than most. Given that they won the most games in the National League in 2019, were projected to win the most in the majors in 2020, and then ended up doing so (by three games) in the 60-game season, there’s little doubt that the Dodgers would have won the NL West and sailed into the 10-team playoffs in a normal year. And although the 2020 playoff format gave some teams a helping hand, it impeded the Dodgers’ postseason progress. Instead of proceeding straight to the division series, the Dodgers had to beat the Brewers in the wild-card round, and instead of having home-field advantage in their actual home park, they played at neutral Globe Life Field from the division series on.

Yes, the playoff format favored depth, and the Dodgers’ NL playoff opponents were injury-wracked: The Dodgers faced the Brewers without Corbin Burnes and Devin Williams, the Padres without Dinelson Lamet (and, after one inning, Mike Clevinger), and the Braves without Mike Soroka. And yes, some pitcher injuries that struck last season stemmed from the oddities of 2020. But by and large, L.A. earned its rings as much as any World Series winner ever does in a sport ruled by randomness. As Dave Roberts said last April, long before he knew his team would wind up in the winner’s circle, “When you look at all of the hurdles, keeping your team together emotionally, and what your players have to do differently to prepare for this season, you can argue it would mean more than going through the duration and grind of an eight-month season. To get to the finish line, and be the last team standing holding that trophy, and knowing what you had to go through to get there, would be as satisfying as any World Series championship.”

So no, the 2021 Dodgers don’t have to prove that they’re full-fledged champions—and by the Bill James definition, at least, they’re already a dynasty. But while they’re working on a repeat, they do have to prove that they’re capable of being one of the best regular-season teams of all time, which wasn’t possible to settle last season. And although the odds are against any team ascending to the top of the all-time single-season wins list, the Dodgers have the talent to make a real run at the record.

Last year’s Dodgers went 43-17, giving them the sixth-best seasonal winning percentage of all time, and the best since 1954. Extrapolating their record over 162 games—by multiplying by 2.7, a number burned into statheads’ brains in 2020—would give them 116 wins, tying them with the 1906 Cubs and 2001 Mariners for the most victories ever. Unlike their championship, though, the Dodgers’ claim to inner-circle regular-season status comes with a caveat. As Wikipedia puts it, “While the 2020 Los Angeles Dodgers finished with a winning percentage of .717, they did so with the benefit of playing a shortened 60-game season.”

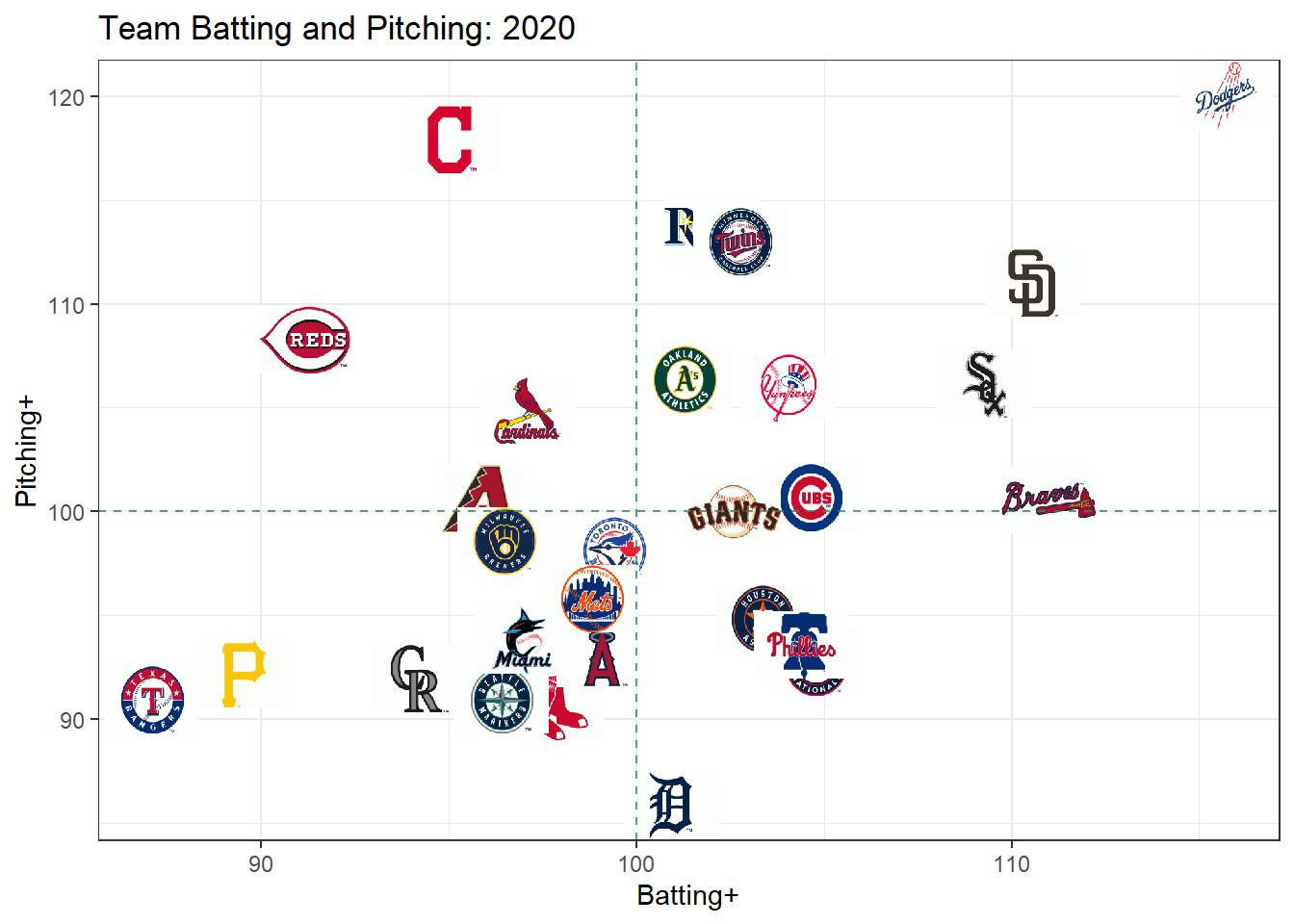

Granted, the Dodgers didn’t fluke their way to a historic clip. Every record estimator—Pythagorean record, PythagenPat, and BaseRuns—agrees that the Dodgers played like a legitimate 43-17 team during the regular season. And they only improved in the postseason, going 13-5 (good for a .722 winning percentage) against the class of the league (and, um, the Brewers). Early this year, analyst Adam Ott graphed 2020 team performance in terms of run scoring and run prevention, accounting for park effects. The Dodgers stood out as baseball’s best team on both counts.

All the Dodgers have to do to approach the record is stay at the same level, but it’s not easy to keep cruising in that winning-percentage stratosphere. It’s not inconceivable that the Dodgers could have kept up their pace over a regular-length season, but injuries, regression, or lousy luck with balls in play or sequencing could have slowed their red-hot roll. As the Dodgers demonstrated in 2013 and 2017, when they won 47 games and 51 games, respectively, over their best 60-game stretches, a sample that size is sometimes deceptive. One of the many minor disappointments of the 2020 season is that the Dodgers didn’t get the chance to prove that this one wasn’t.

However, one of the many minor joys of the 2021 season is that they’ll get to try again. This season, some of the pressure that dogged Clayton Kershaw and Co. throughout their years of playoff failure will be off their backs, though it’s tough to say whether that will have any impact on their pursuit of 116-plus wins (or whether the impact would be positive or negative). But based on talent and depth, these Dodgers have at least as good a chance to set the single-season wins record as last year’s Dodgers would have had in an unabridged season—and probably a better chance than any non-Dodgers team has had in recent memory.

The Dodgers’ chances are as strong as they are largely because the familiar, compelling core of the team that propelled them to a title last year is still present and productive. Thanks to the ever-ripening fruits of their perpetual player-development machine, the Dodgers have avoided growing old during their recent period of sustained success. Although they won their eighth straight division title in 2020—and extended the third-longest streak of postseason appearances ever—their batters, weighted by playing time, were no older than average, and their pitchers were younger than average. Their three most fearsome position players (Mookie Betts, Cody Bellinger, and Corey Seager) are still in their primes, and the aging veterans on the roster are balanced out by youngsters who are still establishing themselves. For every Justin Turner, there’s a Gavin Lux; for every David Price, a Dustin May; for every Kenley Jansen, a Brusdar Graterol. The Dodgers’ farm system has fallen from its recent heights, ranking between ninth and 20th among all organizations this spring, but that’s a concern for future years, not 2021.

The “plexiglass principle” tells us that teams that take a large leap from one season to the next tend to snap back toward their previous level in the following year. But the 2019 Dodgers won 106 games and put up underlying numbers even better than that, so it’s not as if the 2020 team was way out over its skis. Still, too little turnover can be a bad thing for a championship team. As I’ve found before, World Series winners tend to bring back a higher percentage of their players than World Series losers, and that loyalty—coupled, perhaps, with complacency—can cost them. In the 25 seasons of the wild-card era, World Series winners and losers have each amassed cumulative .592 winning percentages in their pennant-winning campaigns. But in the year after their World Series appearances, the champions have declined to .538, whereas the runners-up have regressed a lot less, to .571. Similarly, only 13 out of 25 World Series winners (52 percent) have made the playoffs the following season, compared to 19 out of 25 World Series losers (76 percent).

Although the Dodgers re-signed Justin Turner and Blake Treinen, they didn’t act overly devoted to preserving their playoff roster in amber. Longtime super-sub Enrique Hernández and career Dodgers Joc Pederson and Pedro Báez all left via free agency. Andrew Friedman’s front office also parted ways with pitchers Alex Wood, Jake McGee, Adam Kolarek, and Dylan Floro. The Dodgers had a rich enough roster to replace most of the departed players with internal options—including Price, who opted out of the 2020 season and will return to the rotation this year. (This is, after all, an organization whose staff has been so stacked of late that the club cast aside the second- and third-place finishers in the 2020 AL Cy Young race and still won the World Series.) But instead of standing pat or offsetting the slight losses only with low-profile relief fodder like Corey Knebel and Garrett Cleavinger, the Dodgers—pushed by A.J. Preller’s Padres, who finished six games behind the Dodgers in the NL West but had a hyperaggressive winter—signed the top pitcher on the free-agent market, 2020 NL Cy Young Award winner Trevor Bauer.

By blowing past the competitive balance tax threshold and signing Bauer to a three-year, $102 million deal—which will make him the sport’s highest-paid player this season—the Dodgers became only the second team to land a reigning Cy Young winner in the offseason after winning a championship. (The 1998 Yankees, who inked Roger Clemens, were the first). Bauer, like Clemens, comes with a polarizing personality, a history of troubling off-the-field behavior, a reputation for obsessive preparation, and suspicions of performance-enhancing substance use (in Bauer’s case, the kind you apply to your fingers, not the kind you inject). Unlike Clemens, he has only a single Cy Young Award to his name, not several—and his lone award was won in the 60-game season, against weak competition.

But Bauer, a bat-missing workhorse without any known arm issues, still represents a significant upgrade to what was already a strong and deep rotation. The Yankees, bolstered by the addition of Clemens, repeated in ’99 and then three-peated in 2000 before coming a couple of outs away from a four-peat in 2001 (another Cy Young year for the Rocket). No MLB team has won two titles in a row since those turn-of-the-century squads. The star-studded Dodgers, heavy with hardware, will try to change that.

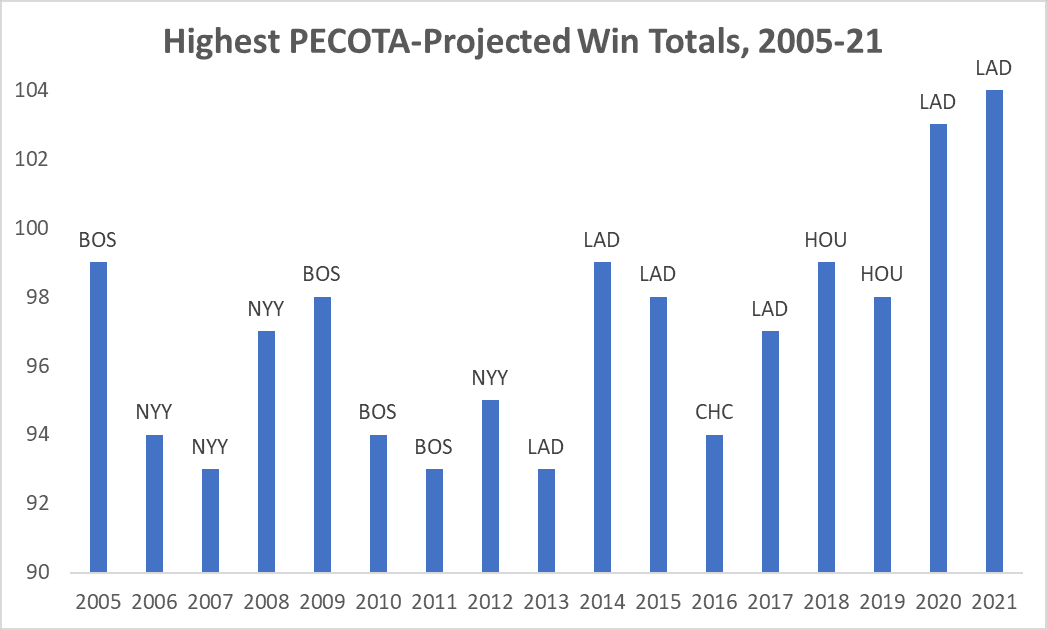

Although the Yankees kept winning World Series after 1998, they didn’t come close to matching the ’98 team’s total of 114 wins. The Dodgers may not either, but they have at least managed to impress PECOTA, Baseball Prospectus’s projection system. Like all projection systems, PECOTA tends toward conservatism: It doesn’t project teams to enjoy perfect health, favorable bounces, and sunny skies all season, although in reality some teams will lead charmed lives and surpass their projections. In its first two seasons, 2003 and 2004, the fledgling algorithm, still hot off of Nate Silver’s spreadsheets and feeling feisty, projected the Yankees to win 109 and 107 games, and the Red Sox to win 104 and 107. But beginning with its third season, the more mature system learned some restraint. From 2005 to 2019, PECOTA never projected a team to win more than 99 games.

That changed last spring, when PECOTA, which failed to project the pandemic, forecasted 103 wins for the Betts-boosted Dodgers. This year, the system is slightly more optimistic: As of its most recent run, the system foresees 104. (The BP website says 103.5, but PECOTA isn’t projecting that Rob Manfred will shorten games to 4 1/2 innings and start handing out half-wins—yet.)

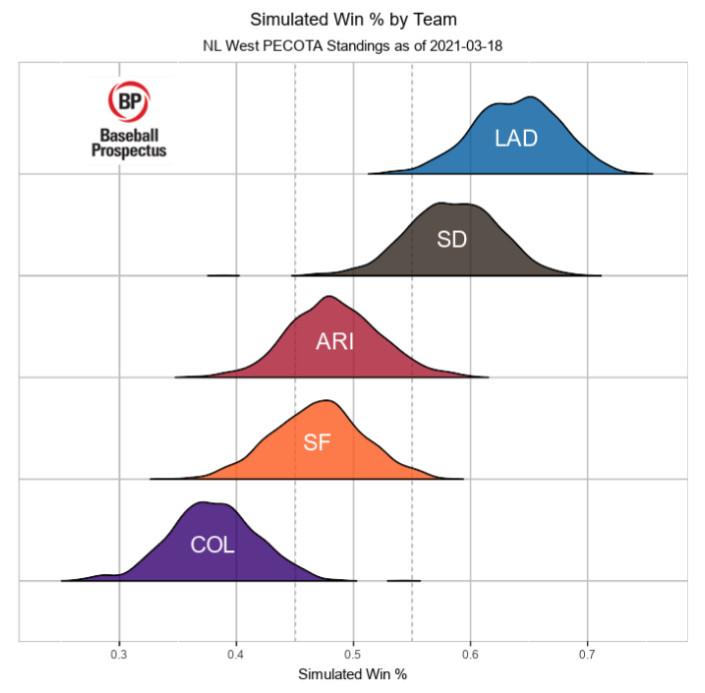

That total of 104 is the mean projection—basically, what the Dodgers will do if everyone plays as projected. In some simulations, of course, the Dodgers do better than that, and in others, they do worse. According to PECOTA’s most recent run of 1,000 simulations, the worst the Dodgers could conceivably do is 86 wins, which is better than the mean projection for all but eight other teams. The best they could do is 120. The number to beat, 116, is the team’s 99th-percentile projection—essentially, a one-in-100 shot. BP’s PECOTA standings page displays this range of outcomes in graphical form: Although the biggest bulge for the Dodgers (representing the likeliest outcomes) is concentrated about halfway between the lines denoting winning percentages of .600 and .700, a sliver of the distribution extends well past .700 (which would equate to 113 wins).

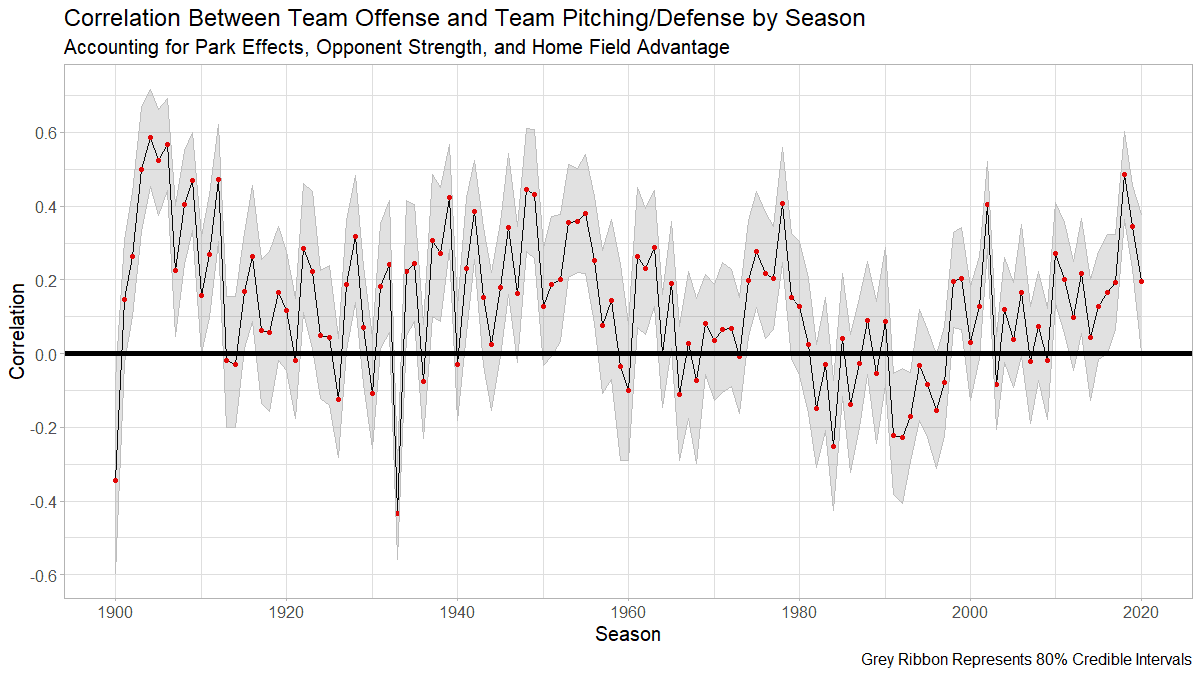

Even a long shot to be the best team of all time is pretty impressive. The Dodgers’ odds benefit from the game’s third-weakest projected strength of schedule, courtesy of the three non-Padres opponents on the chart above, which range from lackluster to hopeless. But baseball’s recent superteam era, which made it easier for the best teams to beat up on the worst ones, may be past its peak. Ott’s research, which accounts for park effects, opponent strength, and home-field advantage, shows that the leaguewide correlation between team run scoring and run prevention—one way to measure parity, because teams tend to dominate when they’re good at both things and get dominated when they’re bad at both—reached a point in 2018 that hadn’t been since since 1906.

Other methods pinpoint the peak of competitive imbalance as 2019. The spread of projected team winning percentages near the start of this season foretells standings that are still stratified, but a little less so than they were entering 2018 or 2019. Even so, there’s reason to think that the Dodgers may be better positioned to plant a new flag than the projections suggest.

As FanGraphs’ Ben Clemens recently argued and BP’s Jonathan Judge confirms, projection systems probably understate the value of the kind of depth the Dodgers have cultivated, which provides a bulwark against injuries. (Bauer believes he could start every fourth day, which would lessen the need for a fifth starter, let alone a sixth or seventh.) That may be particularly true coming off a shortened season, when many teams are fretting about piling innings onto arms that were lightly used last year (and in some cases sat out the season entirely). Although some experienced pitchers may be rejuvenated by the extra time off, others could incur elevated risk; Glenn Fleisig, research director for the American Sports Medicine Institute, says that when weighing workloads in 2021, “players and leagues should consider several factors, including the number of innings pitched in 2020, number of months pitching or not pitching in competition in 2020, and any injuries in 2020.”

With Bauer on board, the Dodgers’ rotation—which trails only San Diego’s in projected FanGraphs WAR—runs roughly eight deep in proven or promising pitchers. Until openings arise, last year’s fourth- and fifth-place NL Rookie of the Year Award finishers, Tony Gonsolin and Dustin May, will be shunted to the bullpen, while top prospect Josiah Gray will bide his time in Triple-A. The lineup is an opposing-pitcher meat grinder. Before adjusting for the NL DH, BP gave the Dodgers’ patient, powerful batting order close to a 20 percent chance to become the eighth team ever (and the first since 1999) to score 1,000-plus runs. That’s less likely with inept pitchers batting in the ninth slot, but the top eight hitters all project to be average or (far) better at the plate, and most have good gloves. (Only the Cardinals turned batted balls into outs at a higher rate than the Dodgers did last year.) Other teams resign themselves to stars-and-scrubs rosters, but the Dodgers, as BP’s Ginny Searle observed, are “just stars-and-stars.”

From Friedman on down to the 26th man, the Dodgers probably care much more about winning 11 games in October than they do about winning 116 or more through September. Given a choice between going all out in pursuit of the record or saving their strength for the playoffs, they’d almost certainly lean toward the latter, even with one elusive title already in tow. Whether they make history or not, the Dodgers should give us a riveting race—either a race against a short list of all-time teams, or a race against their contemporary rivals to the south. Their all-around excellence should be just as apparent in 2021 as it was last year. And this time, we’ll get to watch them strut their stuff 2.7 times as often.

Thanks to Rob Mains, Lucas Apostoleris, and Robert Au of Baseball Prospectus and Adam Ott for research assistance.