How “A Drive Into Deep Left Field by Castellanos” Became the Perfect Meme for These Strange Times

The infamous on-air apology derailed by a Nick Castellanos home run has found life beyond Weird Baseball Twitter—and it may be here to stayLeading off the fifth inning of the second game of a sleepy summer doubleheader on August 19, 2020, Reds right fielder Nick Castellanos prepared for a pitch from Royals reliever Greg Holland, freshly summoned from the pen to preserve a 3-0 deficit. Kansas City catcher Meibrys Viloria called for a fastball and set up on the outside corner, his open glove hovering at the bottom border of the strike zone. Castellanos raised his left leg and stepped toward the plate, and Holland delivered. The pitcher got the height right, roughly, but his four-seamer missed horizontally, tailing in on the right-handed hitter. Through the center-field camera, the pitch looked a little low and inside, but MLB’s Statcast system saw it knee-high, on the inside corner. So did rookie umpire Jose Navas, who raised his right hand and called it a strike.

As Castellanos looked back at Navas to lodge a complaint, Fox Sports Ohio’s veteran Reds broadcaster Thom Brennaman—son of Cincinnati institution and Ford C. Frick Award–winner Marty—geared up for his own delivery in the broadcast booth back at Great American Ball Park. About two hours earlier, in the seventh inning of the first game, the 56-year-old Brennaman had casually uttered a homophobic slur on a hot mic, not knowing that the broadcast was back from commercial. His comment made the rounds on social media, and by the middle of the second game, the pressure and scrutiny had intensified to the point that Brennaman was forced to sign off. But before he did, he made a doomed attempt to restore his reputation and rescue his career. “I made a comment earlier tonight that I guess went out over the air that I am deeply ashamed of,” he began, seconds after the strike call. “If I have hurt anyone out there, I can’t tell you how much I say from the bottom of my heart I’m so very, very sorry.”

On the field, oblivious baseball men stuck to the script, and play proceeded. Again Viloria called for a fastball on the outside corner. Again Holland’s offering went wide of its target. The righty’s second consecutive four-seamer, approximately the same speed as the preceding pitch, also sailed inside, but this one was higher and hittable. Castellanos, a hot hitter who entered the at-bat with a .650 slugging percentage, swings at pitches over the inner part of the plate more often than the average batter, and after being burned by Navas on strike one, he wasn’t about to take another. Castellanos missed much too often on his hacks last season, but when he made contact, he barreled the ball 16 percent of the time, a higher rate than 95 percent of other hitters. The result of this swing was a fly ball that would be one of the sweet 16 percent. Bat hit horsehide hard, and the ball began a 410-foot journey over the left-center-field fence.

In the booth, Brennaman’s next somber sentence had already started. But rather than finish the thought, he reverted without pause to the TV patter ingrained by 33 years of calling major league games. Almost unbidden, a home run call came out, surreally spoken with the same sober intonation as the self-castigation. “I pride myself and think of myself as a man of faith, as there’s a drive into deep left field by Castellanos and that’ll be a home run,” Brennaman said. “And so that’ll make it a 4-0 ballgame.” The mid-apology play-by-play, ESPN’s Pablo Torre says, “was like listening to the band play on as the Titanic was sinking. Except the band was also somehow the iceberg.”

As Castellanos circled the bases, Brennaman went back to doing damage control. “I don’t know if I’m going to be putting on this headset again,” he said, then prostrated himself before, first and foremost, “the people who sign my paycheck.” Despite professing uncertainty about his professional fate, he had to know then that he was almost certainly calling his last game for Fox Sports Ohio. But before he took off his headset, Brennaman left the building with an absurd, Brockmirean blend of meltdown and mundanity, made even more memorable by the irony of the ball touching down just to the left of a Planet Fitness billboard emblazoned with the tagline, “judgement-free zone.”

“Watching Thom Brennaman break the fourth wall and then suddenly reconstruct that wall, in the same breath, remains one of the funniest things I have ever seen,” Torre says. The moment marked the death of Brennaman’s Reds broadcasting career, but the birth of a meme: a copypasta, or block of copied-and-pasted text, that repurposes the apology and accompanying call as both a bait-and-switch joke and a commentary on current events beyond baseball. Brennaman’s use of an anti-gay slur was ugly and damaging, but his on-air attempt to save himself, interrupted by an ill-timed—or, perhaps, perfectly timed—dinger, was a serendipitous parting gift that seems destined to long outlive the defrocked broadcaster’s big league career.

If you want to call bullshit on someone, this is how you respond.Dr. Rosanna Guadagno

“It’s kind of like this decade’s Rickroll,” says journalist Jen Mac Ramos, one of the foremost copypasta practitioners. But more so than the timeless practice of siccing ’80s pop star Rick Astley on unsuspecting readers, the Castellanos prank expresses a point of view. It’s become a common rejoinder used to skewer the sources of all sorts of screwups, scandals, and transparently self-interested public apologies. Dr. Rosanna Guadagno, a social psychologist at Stanford who studies online influence, says, “There’s an interesting group cultural phenomenon going on underneath this that I find fascinating. … If you want to call bullshit on someone, this is how you respond.”

Although Brennaman’s words were bound for meme immortality, it took multiple missteps to cement their status. In the aftermath of the incident, Brennaman became Twitter’s main character. Several videos of the hot-mic moment and of Brennaman’s apology garnered thousands of retweets apiece, and many account owners condemned his use of the slur. But the broadcaster’s offense was still fresh, and the meme’s massive potential was still largely untapped.

Even so, there were signs of the copypasta to come. Accomplished shitposter Craig Goldstein, the editor in chief of Baseball Prospectus, tweeted that he was “considering starting a new career where I insert home run calls into famous, somber moments,” and hundreds of others replied to the tweet with their best suggestions. Assorted tweets from the first day or two show that some users were experimenting with the possibilities provided by an out-of-context Castellanos call. Torre recalls that when he first saw the footage, he “immediately started thinking about what it’d be like if history’s most infamous speeches suddenly had to recognize the laws of play-by-play.” He quickly composed a mashup of Richard Nixon’s resignation speech and the “drive into deep left field,” which became the most prominent night-one example of the proto-copypasta.

But after a flurry of Castellanos tweets in the day or two after the dinger, activity died down. For more than a month, the would-be meme was on life support, with no more than a few tweets per day quoting the Castellanos call. The “drive into deep left field” looked like a two-day wonder that would be buried under a deluge of competing inanities and 2020 terrors. Then came the turning point that would catapult the copypasta to Twitter stardom.

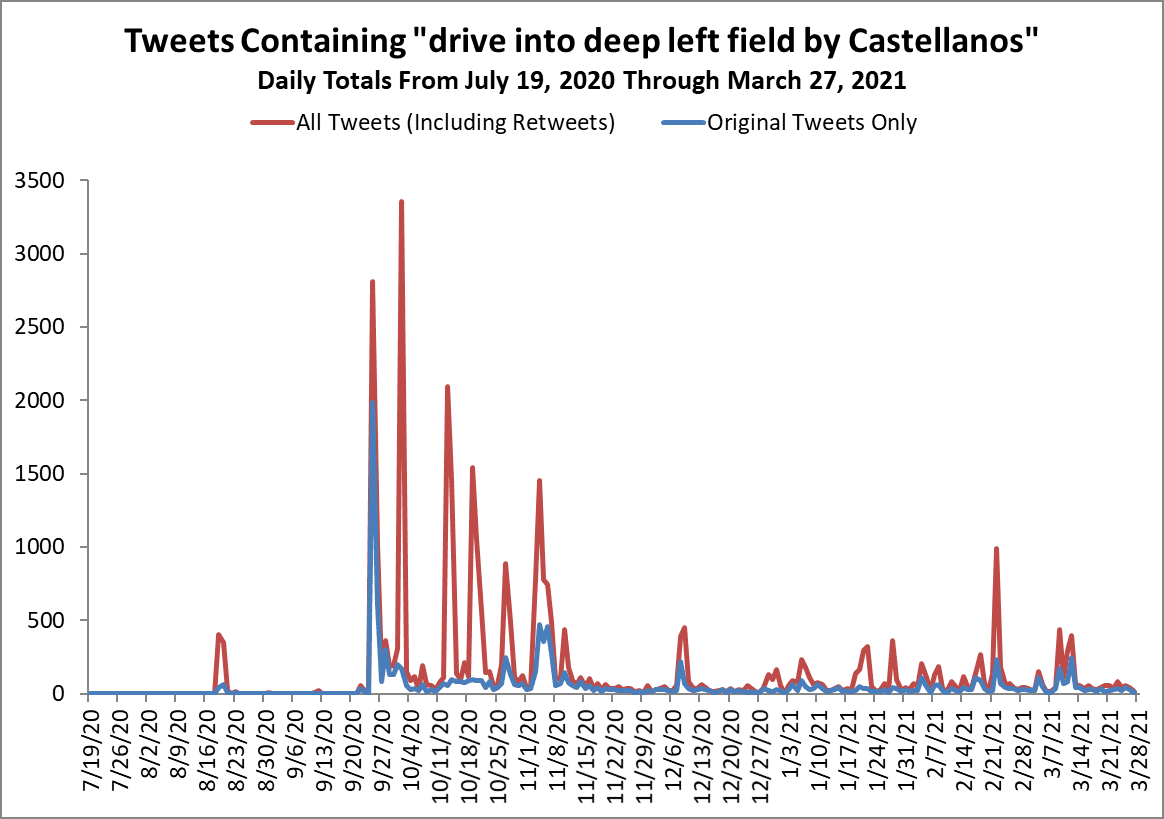

The graph below shows the daily volume of tweets containing the phrase “drive into deep left field by Castellanos” from last July 19 through this past Saturday, based on Twitter’s estimated activity as provided by Twitter analytics company Vicinitas. The blue line represents original tweets only (including replies), while the red line also counts retweets. Of course, this data set encompasses only a portion of the penetration of the Brennaman meme, excluding alternate wordings, image-only examples, or uses on non-Twitter platforms.

Unsurprisingly, nobody tweeted about a “drive into deep left field by Castellanos” in the month leading up to August 19, even though he’d hit some during that span. The blip of August 19 and 20 is easy to see, as is the dearth of tweets in the weeks thereafter. That flatline gave way to a sudden spike on September 25, a momentous date for the Brennameme. In August, the Reds and Fox Sports Ohio had issued late-night statements after the fateful 4-0 ballgame (which ended 5-0) announcing that Brennaman had been suspended from his duties as an MLB and NFL broadcaster and denouncing his words. Brennaman had elaborated on his apology, this time with his headset off and Castellanos safely outside of the batter’s box, in postgame comments to The Athletic and in a Letter to the Editor of the Cincinnati Enquirer the next day. But it wasn’t until September 25 that Brennaman revealed that he’d “decided” to “step away” for good (or at least until someone, somewhere, was willing to rehire him).

In response to Brennaman’s resignation, the Reds tweeted a statement from CEO Bob Castellini in which Castellini elided the reason Brennaman wouldn’t be back, thanked him for his work, called him “a fantastic talent and a good man who remains part of the Reds family forever,” and applauded his unspecified “efforts of reconciliation with the LGBTQ+ community,” whom Brennaman hadn’t mentioned in his on-air apology. The CEO stopped just short of giving Brennaman a medal for meritorious service. “They deserved to have memes tweeted at them all day long for that,” says author Marjorie Ingall, cocreator of the apology analysis site SorryWatch. That sentence was soon carried out: As Defector documented, hundreds of users replied to the Reds’ account by tweeting Brennaman’s apology and Castellanos call either verbatim or with clever variations, as with one user who pretended to be annoyed by the bombardment before segueing mid-sentence into the “drive into deep left field.” As the graph reveals and Ramos remembers, “That’s when it truly became a meme.”

Through that onslaught of almost-identical tweets, the format matured. Like Thom following Marty in the Reds broadcast booth, the Brennameme trod a path paved by predecessors over the past 15 to 20 years at text-heavy sites such as 4chan, home of copypasta legends like Bel-Airing, in which users started out telling serious-sounding stories and then detoured into the lyrics from the theme song to The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. “By the time you got there, you’re like, ‘Damn it,’” says professor Ryan M. Milner, associate chair of the Department of Communication at the College of Charleston. Milner, who studies and writes books about memes and internet culture, explains that the kernel of the Castellanos copypasta is endlessly reproducible. “Once you’ve got that template figured out, which is ‘serious thing, blasé play-by-play of something completely unrelated in the middle, back to the serious thing,’ then you can apply it everywhere, which is what we’re seeing.”

Once you’ve got that template figured out, which is ‘serious thing, blasé play-by-play of something completely unrelated in the middle, back to the serious thing,’ then you can apply it everywhere, which is what we’re seeing.Ryan M. Milner

Over the next two months, Brennamemers grew more imaginative and branched out beyond baseball. Timing played a part in the scale of the spread. “When it became a meme was when there was a lot of stuff in politics going on, a lot of statements diminishing COVID-19,” Ramos says. “So everyone was just like, ‘That’s a bad statement just like Thom Brennaman’s statement. I’m going to put the copypasta on it.’” Because of the constant intersections of Castellanos and politics, Ramos says, “It got to the point where someone thought it was a Russian hack job or something. People had to say, ‘No, it’s the Castellanos copypasta.’”

On October 1, Richard Staff, a writer for Mets blog Amazin’ Avenue, trotted out the Castellanos call in response to the news that President Trump and Melania Trump had tested positive for the coronavirus. “When I saw Trump got COVID, putting the drive into deep left in the middle of his announcement was somehow my first thought, because especially with how serious it was, nobody would expect to get Brennaman’d,” Staff says via direct message. “Obviously, people liked it, and the Brennaman posts began to snowball into the go-to copypasta for news.” Echoing Milner, Staff attributes the template’s appeal to its ability to subvert expectations, saying, “you really don’t see it coming until it already hits you.”

On October 13, a user named Hannah merged the Brennameme with another copypasta to produce the most-shared example of the phenomenon to date. Her tweet has been retweeted almost 4,000 times and liked almost 40,000 times. “It shocked me when the tweet got so big, because I didn’t know that many people found it funny, but the meme really reaches everyone,” she says via DM.

Six days later, Sports Illustrated writer Emma Baccellieri dropped the Brennaman bomb in a tweet inspired by New Yorker writer and CNN legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin’s apology for his “Zoom Dick” disgrace. Baccellieri had doubts about sending her contribution to the Castellanos corpus, because the meme was in no-(Brenna)man’s-land: not new, but not quite established enough to qualify as a classic. But the temptation to tweet was too strong. “It was honestly the first thing I thought of when I saw the Toobin apology, and it was just so funny to me, I had to do it,” she says, also via DM. Thousands of readers were glad she did. “I very much believe it’s earned a spot as [a classic meme] and will live on forever, at least in the vernacular of Weird Baseball Twitter,” Baccellieri adds.

The Brennameme has piggybacked on virtually every major news item of the past several months. Rudy Giuliani’s comments about his Borat appearance. Kim Kardashian’s defense of holding her birthday party on a private island. Electoral maps, electoral votes, and coup attempts. The “Bernie Sanders wearing mittens” meme. Robinhood restricting GameStop trades. Meghan and Harry’s Oprah interview. Meyers Leonard using an anti-Semitic slur on a Call of Duty Twitch stream. The original home run call improbably appeared during an apology for a homophobic, fireable offense, so what’s to stop it from being interjected in any other context? “If a drive into deep left by Castellanos can interrupt that, it can interrupt anything,” Staff says.

Milner says several factors have helped the Brennameme proliferate. First, the fundamental building block: It was tied to a moment that got a lot of internet attention, which primed a large group of people to play around with the form. A recognizable broadcaster uttering a taboo word on the air and then apologizing live would have made news even if the apology hadn’t been derailed, but it was, which leads to the second factor: The situation that spawned it was inherently ludicrous. “This is one of those times when it’s not really good to be multitasking,” Ingall says. As Milner observes, Brennaman “got himself in this situation where he has to be making this intense cultural apology, but he still has a game to call. He’s trying to do them both in the same breath and messing up both of them in the process.” That preposterous sequence, Milner says, “is going to make us laugh. And in the age of the internet, if things make us laugh, then they spread.”

In the age of the internet, if things make us laugh, then they spread.Ryan M. Milner

Then there’s the syntax. The home run call is itself a non sequitur, which enables the Castellanos call to be linked to any preceding sentence just as logically (or illogically) as it was when Brennaman first uttered the infamous lines. Just stick in a comma, add an “as there’s a drive,” and you’re good to go. “The ‘as’ is the killer [word] there,” Ingall says. “It lends itself with that ‘as’ to memeing so well.” The “drive into deep left field,” Baccellieri observes, is also perfectly situated between the “big-picture seriousness” of the “man of faith” clause and the “melancholy vibe” of the headset sentence. “It would be at least 20 percent less funny if the home run had come between any two other sentences in the apology,” she says.

At the risk of overexplaining the joke by citing a highfalutin term from humor theory, the reaction to Brennaman’s disjointed apology is an example of “appropriate incongruity,” or the amusement that results when reality differs from our understanding of how something is going to go. “We have these ideas about what’s expected, what’s appropriate, what’s professional,” Guadagno says. “And then every once in a while, people break those scripts.”

Brennaman broke the script of a standard, sanitized sports broadcast, first with his slur and later with his on-camera confessional. But he also tripped on the steps to a tiresome tradition: the insincere-seeming, pro forma public apology shared in controlled conditions.

Nobody knows exactly what was in Brennaman’s head as he spoke his last words for Fox Sports Ohio, but his apology failed the sincerity sniff test in any number of ways. The extended delay between the offense and the apology. The irrelevant reference to being a man of faith. The “if I have hurt anyone.” The initial failure to apologize personally to the people he hurt most. The “That is not who I am. It never has been.” As Ingall says, with the wisdom of one who’s critiqued countless apologies, “It’s obviously at least a part of who you are. So to say, ‘Oh, this isn’t really me,’ when we know it’s him—there’s really no apology that’s going to work well for that. And there shouldn’t be. We believe in forgiveness, but you have to earn it.”

Apologies are a staple of online life in the 2020s, a time of shifting norms and diminished privacy. Whenever a Milkshake Duck is discovered or a polished public persona slips, a reckoning comes, followed by a PR-approved Instagram post or a practiced rehabilitation tour. If Castellanos had taken strike two, maybe Brennaman could have submerged himself in that sea of sorrys and avoided disproportionate attention. “If it was just the formulaic apology, then there would have been an eye roll and maybe some commentary about that,” Milner says. “We would have moved on. But the incongruity of him calling a play in the middle, it just further punctuates how rote this must have been, that he wasn’t even heartfelt enough to get through it without turning to this play call.” The apology’s performative nature was laid bare, all because of a drive into deep left field by Castellanos.

Memes, Milner says, are all about reappropriating concepts from one situation and applying them to a second situation. “When you do that remix,” he says, “you’re saying Thing B is like Thing A. In this case, Thing A is this insincere, forced apology, evidenced by this cut-in for a play call. So when you apply it to Thing B … then you’re saying, ‘This is also an insincere and forced apology.’” The Brennameme, then, is a shorthand, a means of signaling a cynicism born of being fooled before.

“When it’s clear you’re lying, an apology sucks,” Ingall says. So “it can be both cathartic and helpful to point out a knee-jerk bad apology or corporate-speak.” The Brennaman meme makes us laugh, but it also offers an outlet for fake-apology fatigue. “The more we all call bullshit on that apology,” Ingall says, “I think that’s good.”

Once you get hooked on Castellanosing, it’s tough to walk away. Ramos intended to retire after working the Castellanos call into the lyrics of “Do-Re-Mi” from The Sound of Music on October 17. They were lured back into action on October 27 by a Fox Sports statement about Justin Turner’s positive COVID-19 test. That was going to be their last Castellanos tweet, too, but then the election rolled around. As a substitute for doomscrolling while waiting for results, Ramos built a Twitter bot to automate the copypasta. The fruits of their labor, @DriveIntoDeepLF, has upward of 3,000 followers and automatically quotes Brennaman when anyone tweets at the account. Ramos, who’s no longer contemplating retirement, has occasionally commandeered the account to tweet some popular originals.

Scanning the bot’s mentions makes Ramos aware of what’s causing copypasta uses. When Meyers Leonard tweeted a much-maligned apology, Ramos says, “Everyone was basically like, ‘This just sounds like a Brennaman apology.’ And I was thinking, ‘I guess Brennaman is now the standard of what a bad apology is in sports.’” Days later, an Oklahoma high school basketball announcer said the N-word on a broadcast and, as part of an eight-paragraph press release, blamed the racist remark on spiking blood sugar. That excuse might have set a new standard for suspect apologies, but it was swallowed by the Brennameme.

“I definitely did not expect it to still have life in March,” Ramos says of the meme. “And I feel like at this point it’s just going to stick around.” Although the Twitter activity has subsided some since late last year, the meme has enjoyed a long tail of attention, buoyed both by a free-flowing stream of poor apologies and by a trickle of news about Brennaman or Castellanos.

In October, MLB pitcher Robert Stock replied to Staff’s Trump tweet to say, “I’m not sure this format will ever get old.” YouTuber Bailey (of Foolish Baseball fame) responded by Brennameming him. When the Roberto Clemente League in Puerto Rico hired Brennaman in December to do play-by-play, Bailey kept the format but changed the language, enlisting a translator to transcribe the Brennameme into Spanish.

In January, Twins writer Brandon Warne recreated the Castellanos homer in MLB The Show and synced it up with the call:

When Castellanos turned 29 on March 4, the Reds bravely ventured into prime meme territory to tweet birthday wishes. Predictably, most of the responses referenced the right fielder’s drive into deep left. In mid-March, a Sporcle quiz about Brennaman’s apology appeared. And last week, San Diego sportscaster Ben Higgins seamlessly slipped a spoken version of the meme into a highlights package as he narrated a Castellanos spring-training homer.

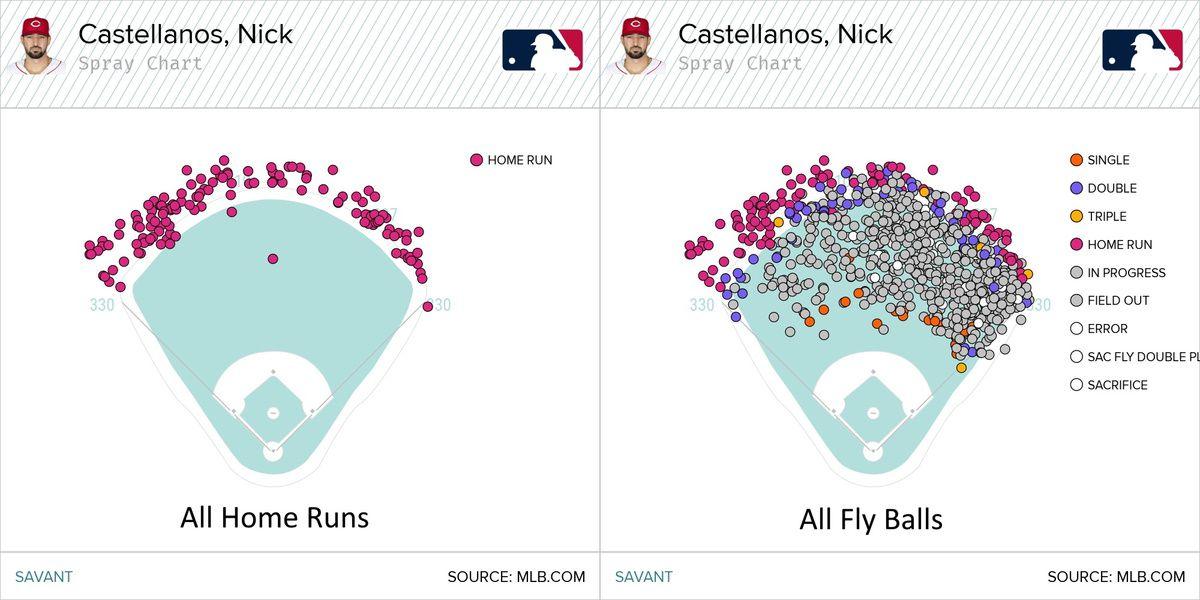

Castellanos has hit 90 homers over the past four seasons, which ties him for 37th in the majors. Like most right-handed hitters, Castellanos lifts most of his flies to right field, and he has home run power to all fields.

But wherever he hits his homers into 2021, every new tater will generate a notification and present another opportunity to tweet.

Despite being one of the most-mentioned figures on Baseball Twitter, Castellanos doesn’t have an official account. And if he ever does decide to join, he’ll have to ignore his notifications. Last October, Bradford William Davis of the New York Daily News mused that Castellanos “is going to log on one day, search his name and be so amused.” Whether he’s amused, perplexed, annoyed, or indifferent remains a mystery; the Reds declined to relay an interview request for this story, and his agent didn’t respond to an inquiry. But maybe it’s better not to know. Castellanos was an unwitting chaos agent in a matter much larger than him. His surname belongs to Twitter now. And if he has to be internet famous, at least it’s for hitting a home run.

Regardless of how Castellanos feels, the meme boosted Baseball Twitter’s spirits during a painful period. “It was so good to see the baseball community come together to make something good out of a situation like that,” Hannah says.

Before Ramos became a one-person copypasta machine, they considered whether poking fun at the apology could exacerbate the damage done by Brennaman. “As a queer person, I don’t want to take away from the seriousness of saying a homophobic slur on the air,” they say. But they came to view the purpose of the copypasta as punching up at the person who committed the transgression, not mocking the people he harmed. “I have mostly felt OK about it, because it’s pointing out: Don’t do this,” Ramos says. “Otherwise, you will become shamed on the internet, and you will become an everlasting copypasta meme.”

Kelvin Brumm and Ginny Searle, who wrote about Brennaman’s use of the slur and baseball’s history of homophobia at Baseball Prospectus, say they also see the upside of the meme. “Over the past few decades there has been a push by some within historically marginalized groups to reclaim some historically pejorative words and phrases,” Brumm says. “Though I wouldn’t say this is wholly analogous, I appreciate people being able to take Brennaman’s ensuing comments and make them into something genuinely funny.” Brumm concludes, “In my personal journey as someone who is gay, I’ve come to find that it helps to laugh when you can at life, and since this joke is only at the expense of his apology … I don’t see anything problematic about it.”

Memes like the Castellanos copypasta can become a community’s common language, a means of locating like-minded people and building bonds in online environments. “The people who understand the backstory and recognize the meme are going to get a dose of pleasure out of the fact that they see the meme … they know what it means, and they know that they’re in an exclusive group of people who understand it,” Guadagno says. Most memes require less specialized knowledge than the Castellanos copypasta, she says, “yet somehow it still caught on and broadened beyond that group,” she says. Not that it’s easy to explain with words. “No explanation can come close to just showing the video,” Baccellieri says.

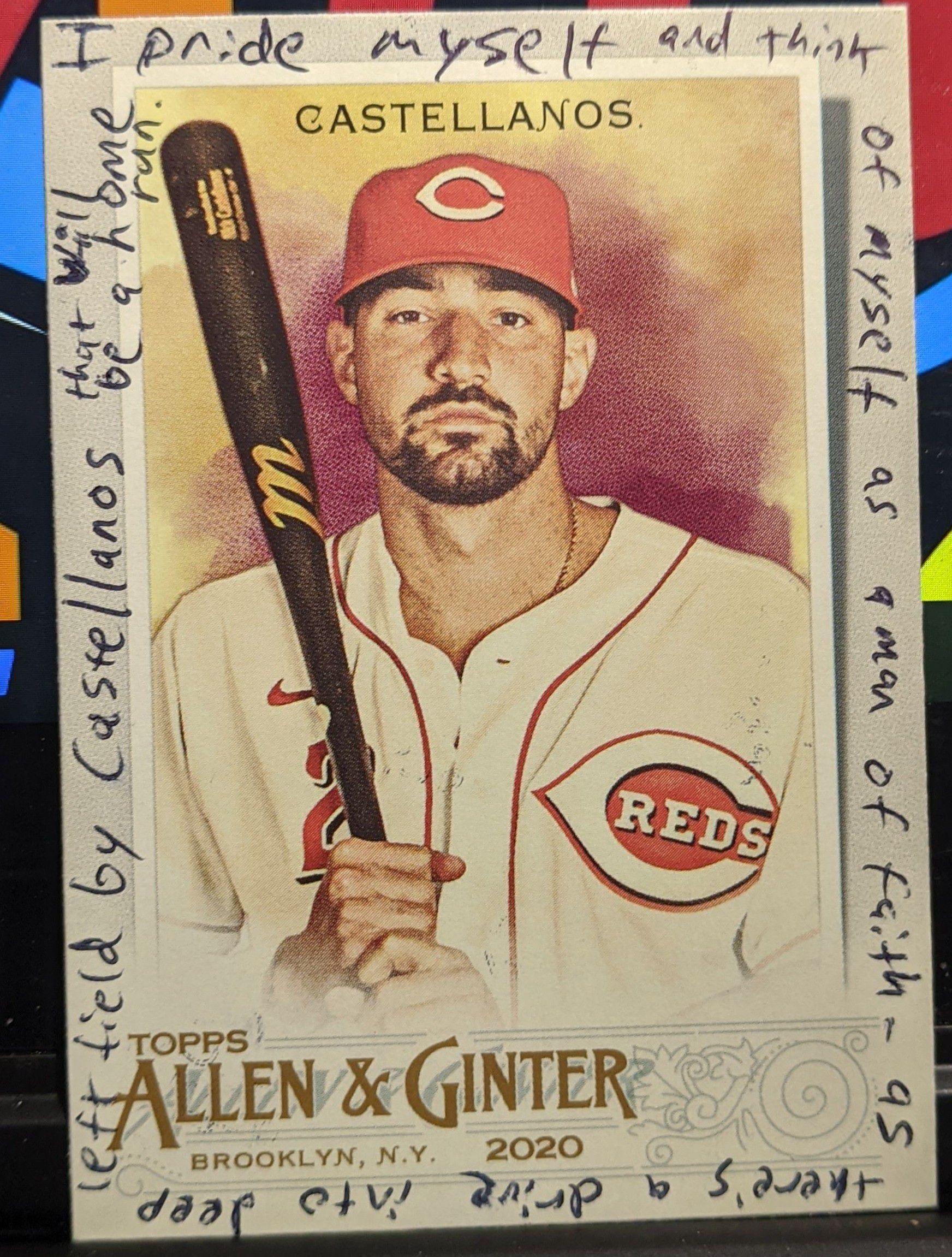

Baseball has hardly been a hotbed of famous memes, thanks to its older demographic, fans’ regional relationships to the sport, and MLB’s misguided GIF embargoes. The Castellanos copypasta is a rare crossover exception. “I’ve been on the internet for way too long, and I’ve seen a lot of memes come and go, but this is the one thing in Baseball Twitter that I’ve seen that my friends who are not involved in Baseball Twitter at all send me,” Ramos says. One friend gave Ramos a physical keepsake: a Castellanos Topps card defaced by the Brennameme.

Unless his stint in the Clemente League was the beginning of a Brockmire-esque journey back to the big leagues, August 19 was (4-0) ballgame over for Brennaman. But the keepers of the Brennameme will keep coming together to make the best of a bad (and extraordinarily strange) situation. Whenever an offender says this isn’t who they are, fails to specify what they’re sorry for, or appends an “if I offended anyone,” the words of the exiled Brennaman will be there to greet them, as there’s a drive into deep left field by Castellanos and that’ll be a home run. And so that’ll make it a 4-0 ballgame.

An earlier version of this piece misstated where Brennaman was when he issued his apology.