All those situations in which contrasting extremes are most closely and variously intermingled, are the deepest and richest in interest, and conduce most remarkably to human development.—Wilhelm von Humboldt

In human history, it is extremes which lie most closely together; and the condition of external things, if we leave it to continue its course, undisturbed by any counteracting agency, so far from strengthening and perpetuating itself, inevitably works out its ruin.—Also Wilhelm von Humboldt

In the hours before the first pitch of the American League wild-card game on October 3, 2018, Billy Beane and Brian Cashman palled around behind the hitting turtle on the field at Yankee Stadium, where the two teams they’d built would do battle. Cashman, the New York Yankees’ general manager, had dressed down in khakis and a checked, cream-colored jacket. Beane, befitting his superficially fancier title as the Oakland Athletics’ executive vice president of baseball operations, wore a suit and skinny tie. Amid the bustle of batting practice, the big man with the small budget and the small man with the big budget remained rooted in foul territory, where they talked and laughed alone.

“Our conversations now are as much personal as they are professional,” Beane says today. “We’ve definitely had some heart-to-hearts.” At the time, neither he nor Cashman appeared pained by the prospect of facing off in a single game that would tell them little about their teams’ talent, but would still send one of their painstakingly constructed squads home. Instead, they fantasized about forgetting the game altogether. Cashman half-seriously suggested that the two go out to dinner and agree not to check the score until a prearranged time, when the contest would be close to concluded. They didn’t end up doing it, Beane says, then hastens to add, “Though I would have.”

By then, the two men had been foes and friends for more than 20 years, and the unlikely faces of their franchises for at least the last few. They’d repeatedly overwritten and reassembled their rosters, long outlasting any of the athletes they’d inherited—or, for that matter, the GMs they’d gone up against in the 1990s, an era whose statistics and technology were closer to Ty Cobb’s than today’s. The 2018 A’s, backed by the game’s skimpiest payroll, had 97 wins; the Yankees, who spent more than 2.5 times as much—an austere year for them—had 100. When it was over, Beane won awards. Cashman won the wild-card game. They’d both been there before. It was one more year among many for the improbably long-lasting leaders of baseball’s quintessential small-payroll and big-payroll franchises.

“My observation is that their relationship is unique, at least from Billy’s end,” says Beane’s longtime second-in-command, David Forst, who joined the A’s in 2000 and was promoted to GM when Beane was elevated to executive VP in 2015. “I think he and Brian share this bond of having been in that chair as long as they have. And I think he can talk to Brian in a way that he doesn’t really have with a lot of people left doing this job.”

This month, Beane and Cashman entered their 24th seasons. “It’s a job that you don’t really think of anybody holding for that length of time,” says author Michael Lewis. “If you would have asked me, back when I was working on Moneyball, if Cashman would still be in the job even 10 years later, I would have said, ‘No way.’ It was such a volatile job.” Yet here he is, and Beane besides. You can tell the story of the sport’s upheaval over the past quarter-century through the careers of these constants at MLB’s spending extremes. But first you have to trace the origins of the ballad of Billy and Cash.

The friendship between the 59-year-old Beane and the 53-year-old Cashman, which has spanned countless conversations, four decades, and three October trials, began with one bum shoulder. In the summer of 1997, the Yankees and the San Diego Padres tried to trade troublesome 32-year-olds. The Yankees’ Kenny Rogers and the Padres’ Greg Vaughn, who were in their second seasons with their respective clubs, had the same salaries ($5 million a year) and the same statuses: buried behind other players and displeased about it. Both burials were due to disappointing performance. Rogers, a left-handed pitcher, had been dropped from the rotation thanks to a 5.90 ERA; Vaughn, a power-hitting outfielder, had lost his starting spot in left field to a 38-year-old Rickey Henderson and was batting .224 with a sub-.400 slugging percentage.

A few weeks before the trade deadline, on Independence Day, the two classic candidates for changes of scenery were seemingly set free. The Yankees agreed to send Rogers, Mariano Duncan (a fellow frequent target of owner George Steinbrenner’s wrath), and a Double-A arm to the Padres for Vaughn and two minor league pitchers. But before the teams could complete their cross-country exchange, one hurdle had to be cleared: The players had to pass physicals. That posed a potential problem, because of another commonality between the two centerpieces: Both had surgically repaired shoulders. Theoretically repaired, at least. When Vaughn flew to New York and stretched, flexed, and coughed for the Yankees’ medical staff, the doctors concluded that he had a torn right rotator cuff. The swap was off.

Staying put and playing through the purported injury worked out fine for Vaughn, who regained his starting role after the Padres dealt Henderson to Anaheim in August. The slugger would finish fourth in NL MVP voting in each of the next two seasons, hitting more home runs than anyone except Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Ken Griffey Jr. (not counting the three he launched in the 1998 playoffs—including two against the Yankees, who swept San Diego in the World Series). Rogers would bounce back to be one of the top 10 pitchers in baseball (by Baseball-Reference WAR) over the same span. But he wouldn’t do it for the Yankees. The lefty barely lowered his ERA over the rest of the ’97 season and couldn’t crack the club’s division series roster. When November rolled around, Rogers was back on the block. The slumping southpaw would soon escape New York—and, in the process, unite Beane and Cashman.

In 1997, the Athletics had finished with the worst record in baseball, 65-97. Despite playing in a pitcher’s park, they allowed the most runs of any team. “Our pitching was absolutely awful,” remembers Beane. He was the one charged with changing that. On October 17, the 35-year-old Beane was promoted from assistant general manager to general manager, succeeding lawyer and former Marine Sandy Alderson, who had led the franchise to three pennants and one title since taking over as GM in 1983. Alderson, Beane’s mentor, had already begun to deconstruct the team’s decrepit roster, trading Gerónimo Berroa to Baltimore in June and McGwire to St. Louis in July. It would be Beane’s job to build the club back up again. And he’d have to do it without spending much money.

As inconceivable as it seems today, the A’s weren’t always small spenders. In 1991, the year after winning their third consecutive pennant, the A’s had the highest payroll in the majors. The Yankees, led by GM Gene Michael, were still extricating themselves from a Steinbrenner-induced funk while the Boss was suspended. Their payroll ranked eighth. The next year, the two teams placed fifth and sixth in spending, with Oakland edging out the Yankees. In 1993, the Yankees ascended to third and the A’s sank to 12th; Oakland hasn’t outspent the Yankees in any season since (or really come close), and the Yankees haven’t had a losing record. But it wasn’t until 1996, after the death of former A’s owner (and Levi Strauss billionaire) Walter A. Haas Jr. and the sale of the team to two local real estate developers, that Oakland’s payroll cratered. With far stricter spending constraints in place, Alderson started applying the principles of sabermetric trailblazer Bill James to identify undervalued players. He passed his appreciation for the empirical approach on to his protégé.

You know the rest of the story. Michael Lewis wrote a book about it, in which Beane said, “If we do what the Yankees do, we lose every time, because they’re doing it with three times more money than we are.” What Moneyball didn’t mention is that Beane’s efforts to reshape the roster started with a Yankees collab.

If Nintendo of America can have a president named Bowser, Starbucks can have a COO named Brewer, and Shoe Zone can have finance directors named Foot and Boot, then the Yankees can be excused for their GM’s on-the-nose name. But in the fall of ’97, Cashman was a few months away from assuming the office he still holds. Bob Watson, who was hired after the ’95 season, would be the GM until the following February, when he resigned to preserve his health, both mental and physical. “I knew Bob was under siege, because working for the Boss in that capacity was pretty impossible,” Cashman says. “But he didn’t share with me what he was thinking.”

On February 2, 1998, Watson told Cashman, then the assistant GM, that he was abdicating the office and recommending the 30-year-old former intern as his replacement. Cashman attempted to talk him out of it. “I spent that morning trying to convince him to unring that bell, but Watson was like, ‘Nope, I’m done,’” Cashman says. Twenty-three years later, Watson’s successor still hasn’t said “I’m done.”

The GM-in-waiting was ready to replace Watson when the call came because both Watson and Michael had taken his training wheels off early. One year at the Braves’ spring training site in West Palm Beach, Michael had dispatched a young Cashman to ask Atlanta’s Bobby Cox about the availability of Braves starter John Smoltz. “It was awkward,” Cashman recalls. “He told me, ‘Well, if Gene Michael wants to talk to me about John Smoltz, you have Gene Michael call me.’ Like, ‘Yessir, Mr. Cox.’”

It got easier. Before he took over the top spot, Cashman cosplayed as GM with Watson’s younger counterparts on other teams. “I remember Bob said to me, ‘Half these guys in this game I don’t know,’” Cashman says. “He divided it up half and half, and he goes, ‘You deal with those clubs, I’ll deal with these.’” Watson handled dealings with the old guard, many of whom were former major leaguers or minor leaguers—40-, 50-, or 60-somethings such as Ron Schueler of the White Sox, John Schuerholz of the Braves, Pat Gillick of the Orioles, and Terry Ryan of the Twins. Cashman took the lead with the new breed, including the Padres’ Kevin Towers and a fresh-faced former outfielder in Oakland. “That’s how I started getting to know Billy Beane,” Cashman says.

In the fall of ’97, it was obvious that the A’s needed arms and that Rogers needed a new place to play. It was equally clear that Oakland couldn’t afford him unless the Yankees kicked in a considerable portion of the $10 million he was due through the next two seasons. Beane and Watson started talks, but Watson soon passed the conch to Cashman. “It went really smoothly,” Beane says. “We hit it off real well.” Cashman saw it the same way. “Kindred spirits, man,” he says. “It felt like we got along really well immediately, laughed at the same stuff, and there was a lot of alignment or connection. It was fun to have conversations with him.”

Those conversations yielded a deal: Rogers for third baseman Scott Brosius, whom the A’s agreed to protect in the upcoming expansion draft and then send to New York. To make the money work, the Yankees would pay half of the portsider’s salaries in 1998 and 1999—no small amount at a time when MLB players were making $1.4 million, on average, or roughly a third of where the baseline peaked before the sport’s recent spending downturn. Beane’s first trade was done. “Brian wasn’t officially the GM, but it almost seemed like it was his first trade as well,” Beane says.

Rogers’s inflated ERA would have made him feel at home on Oakland’s porous ’97 staff, but the A’s were gambling that the Gambler would pitch as well as he had in Texas. The Yankees hoped they were buying low, too. Brosius was atrocious at the plate in 1997, but he was still a fine fielder and had hit well in ’96. (Nowadays, we would note that his BABIP was low, and we’d definitely look into his xWOBA.) Both bets paid off. In 1998, Brosius had his lone All-Star season, a five-win campaign for one of the best teams of all time. Rogers had a career year too, which helped the A’s make a modest improvement to 74 wins.

But the benefits of the Rogers resurgence went well beyond his direct contribution. On July 23, 1999, the A’s traded Rogers to the Mets for Terrence Long and a minor leaguer. Long, who hit the double that set up Derek Jeter’s famous “Flip Play” in the 2001 ALDS, played for the A’s for four years and later helped bring back Mark Kotsay. But Beane also says that the money the Yankees sent Oakland in the Rogers deal allowed him to make multiple trades at the ’99 deadline. The A’s went back to the well with the Mets to land Jason Isringhausen, acquired Randy Velarde and Omar Olivares from the Angels, and added Kevin Appier from the Royals. The next year, Velarde brought back Aaron Harang, and Appier’s departure via free agency netted the A’s two first-round draft picks, including the one they used (to Beane’s chagrin) on another future trade chip, Jeremy Bonderman.

“[Kenny’s] return to form created so much asset value that was so critical to a club like ours going forward for the next, gosh, you could even say decade, in some sense,” Beane says. “Maybe that’s a little bit of hyperbole, but if you look at the players we acquired, the draft choices we got, the way those players contributed to our resurgence, it really all started at Kenny Rogers.”

So did Beane’s bond with the Yankees GM. “And then,” Beane says, “he proceeded to knock us out of the playoffs and create highlight films for commercials for the next 30 years.”

The Rogers trade, Cashman confirms, “was the beginning of a friendship that has lasted to this day.” When they made the trade, he and Beane were the newest of the new blood and no more than acquaintances. Now, Beane says, they’re “two of the senior guys and very close friends.” He adds, “Somehow we both survived up to this point, and in two challenging environments in two different ways.”

Although the two took different paths to their positions, their trajectories bent toward baseball at the same age, and they advanced through their front offices at a similar pace. An 18-year-old Cashman snagged a Yankees internship through his father and a family friend, both of whom knew the horse-obsessed Steinbrenner. (Here’s where I mention that I was once a Yankees intern, too. I did mostly mindless tasks in baseball operations from mid-2009 to mid-2010 but wasn’t offered a full-time position—an example of Cashman’s keen eye for front-office talent, or in my case, the lack thereof.) An 18-year-old Beane was drafted by the Mets, passed up an offer to play football for Stanford as John Elway’s heir apparent, and made his pro debut in Little Falls, New York, on the same Low-A roster as his future friend and colleague, J.P. Ricciardi.

“Billy was always inquisitive,” says Ricciardi, who’s now a senior adviser to another ex-Athletics lieutenant, San Francisco Giants president of baseball operations Farhan Zaidi. “I don’t think he ever talked to me about, ‘Geez, I’ve got a grand scheme, I’d like to own a team or run a team.’ But I think he was always interested in the bigger picture of sports. … He’s a bright guy, and he doesn’t want to be stuck in that plain old jock mentality that you play and that’s all you do.”

Cashman graduated in 1989 and passed up law school to take an entry-level job with the Yankees. Several months later, the 27-year-old Beane, whose .219/.246/.296 slash line over parts of six seasons belied his physical gifts, walked away from Oakland’s spring training roster and asked Alderson for a scouting job. In late November ’92, Cashman made assistant GM; less than eight months later, Beane matched him. They got their GM jobs less than four months apart. “This is something I’ve looked forward to doing since I was 18,” Beane told reporters. “I’ve always wanted to run a ballclub.” By contrast, Cashman, the second-youngest GM ever when he was hired, says, “I never had a goal of, ‘I want to be a GM.’”

On Alderson’s advice, Beane had passed up offers from other teams. His mentor told him that he wasn’t quite ready, and that the offers weren’t quite right. “He said, ‘The goal in this job isn’t to become a GM,’” Beane remembers. “‘The goal in the job is when you do become one, you do it as long as you want to. You don’t let somebody else decide.’” Cashman had mentors too, in Michael and Watson, but they didn’t give him the same advice. Before Cashman, no GM serving at Steinbrenner’s pleasure (or much more often, displeasure) had made it much more than five years. Michael was the longest-lasting GM in Steinbrenner’s disordered stable, and half of his longer, second stint elapsed while the Boss was suspended. “There was no expectation of longevity in this position here in New York,” Cashman says. “It was always a short-term position.” Beane says he always aspired to be “invaluable enough to the organization that you did get to work as long as you want it,” but Cashman credits part of his resilience to never taking it for granted that he’d have a home. “I never assume anything,” he says. “I’m not assuming I’m going to be here.”

After consummating the Rogers deal—you always remember your first—the two wouldn’t team up on another trade until the summer of 2002. But they grew together at the annual GM meetings, interminable talkfests that stretched on much longer and allowed for more socializing than they do now. The tables were set alphabetically by city name, so the friends from New York and Oakland always sat side by side. “We would just cut it up with each other, like two little kids in class,” Cashman says. “Either passing notes to each other to make ourselves laugh, or talking out of turn amongst each other while the speaker was presenting on behalf of Major League Baseball or whatever.”

We would just cut it up with each other, like two little kids in class. Either passing notes to each other to make ourselves laugh, or talking out of turn amongst each other while the speaker was presenting.Brian Cashman

One year, Cashman cut the high jinks and staged an intervention about an unhealthy habit of Beane’s. He hadn’t forgotten the stained, decaying teeth of the workers who went around with Red Man in their mouths on the hardscrabble horse farm in Lexington, Kentucky, where he grew up. Nor had he forgotten a spring training presentation on the dangers of dipping by Joe Garagiola Sr., who’d shown footage of a committed tobacco chewer who’d had half his jaw removed. “I used to chew tobacco,” Beane says. “Cash looked at me one day when we were at the GM meetings, and he goes, ‘Dude, are you still dipping?’ And I go, ‘Yeah.’ He goes, ‘You’re too smart to do that.’ And I go, ‘You’re right. Why the hell am I doing this?’ And I quit.”

As friends and front-office survivors, the man who’s famous from Moneyball and the man who’s famous for spending the most money make an odd-couple pairing. The son and grandson of military men, raised in San Diego, and the son of a heartland horse breeder whom Cashman says “broke every child labor law in the country.” A former first-rounder who made the majors, and a non-prospect whose playing career ended in Division III. A 6-foot-4 stunner who was semi-plausibly played by Brad Pitt and whose body was built to sell jeans—“He’s got some shoulders,” former Minnesota manager Cal Ermer gushed about the “well-built boy” when Beane joined the Twins—and a 5-foot-7 scrapper whose height and hairline made George Costanza his most frequent physical comp. Similar circumstances and senses of humor bridged the differences in upbringing. “He didn’t bring whatever his background was to the table as any obstacle, nor did I,” Cashman says. “We were just two of the younger crew, just trying to find our way now in these new opportunities, and we got along great.”

It’s not unusual for friendships to endure for 20-plus years. But to borrow a phrase from the Moneyball movie, it’s incredibly hard for general managers to survive and thrive for that long in a single setting. “I don’t think people realize how difficult it is to do what each of them is doing,” says former Rockies executive Dan O’Dowd, who had the GM job for 15 years in Denver but compares how he felt after the 10th year to spoiled milk. (Epstein and Bill Walsh could commiserate.) Because Cashman and Beane have bucked the typical turnover, “They’re living a very outside-the-box general manager’s life,” says Ricciardi, who is now working for a fourth front office. “It doesn’t work like this for 90 percent of other people. They’re able to have a job that they like with security in a place where they’re comfortable, and they live where they like to live. Baseball’s not built like that. It’s an abnormality, what they’re doing.”

“Abnormality” is an understatement, as is “90 percent.” “Almost unprecedented” and 99-point-something percent would be more accurate. Beane and Cashman are in their 24th consecutive seasons serving as the highest-ranking baseball operations executives of the A’s and Yankees, respectively. Only one person in a position akin to theirs has ever had an uninterrupted run that long with one team: Cashman’s distant predecessor Ed Barrow, a Hall of Famer who steered the Yankees for 24 seasons from 1921 to 1944. Some GMs have served longer across multiple teams, but Beane and Cashman have surpassed all other tenacious single-teamers, including the Pirates’ Joe L. Brown, the Tigers’ Jim Campbell, and the Giants’ Brian Sabean. If Beane and Cashman make it into 2022, they’ll break Barrow’s record.

They’re able to have a job that they like with security in a place where they’re comfortable, and they live where they like to live. Baseball’s not built like that. It’s an abnormality, what they’re doing.J.P. Ricciardi

“The only GMs longer[-serving] than Barrow/Cashman/Beane would be owner/operators and manager/GM John McGraw,” historian, author, and Barrow biographer Daniel R. Levitt says via email. Levitt notes that owners in earlier eras (including Connie Mack, Charles Comiskey, Clark and Calvin Griffith, Barney Dreyfuss, and Horace Stoneham) often made their own moves, and McGraw managed and general-managed the Giants from mid-1902 to mid-1932. Levitt defines one of McGraw’s contemporaries, the Tigers’ Frank Navin, as “the first modern GM” and the strongest challenger to the Barrow-Cashman-Beane record, but Navin quickly acquired a substantial ownership interest, and Levitt argues that after 1908, “he was no longer a classic GM because as an owner-operator he was not subject to being fired.” (Beane, by contrast, has only a small minority ownership stake, which was once 4 percent but has reportedly dwindled to approximately 1 percent.)

That the greatest threat to the modern duo’s streak comes from the man who signed Cobb reinforces the scarcity of comparable careers. Though Alderson remains in the game as the Mets’ president, Cashman and Beane are almost the only GMs from their rookie year who are still standing—and they are the only one still standing in the same surroundings. Of the GM class of 1998, only Beane, Cashman, and Dave Dombrowski continue to control a team’s baseball operations department. And Dombrowski, who was on his third team in ’98, has made three more moves since then (and sat out 2020).

When analyzing outliers like Beane and Cashman, thoughts naturally tend toward the Hall of Fame. It’s no easier to enter the Hall as an executive than it is as a player. Only seven men who spent most of their careers as GMs are in the Hall of Fame: Barrow, George Weiss, Branch Rickey, Larry and Lee MacPhail, Pat Gillick, and Schuerholz. “If winning World Series is the only way to get into the Hall of Fame as an executive, then Billy Beane doesn’t have much of a chance,” ESPN’s Rob Neyer wrote almost a year prior to the publication of Moneyball. Beane may have bolstered his case in the intervening decades by putting together many more competitive teams and by becoming synonymous with the ascendant sabermetric movement, but Neyer’s contention is just as true today. Beane’s shit still hasn’t worked in the playoffs, partly because Cashman’s clubs have barred his way. And both Beane and Cashman will contend with contemporaries who’ve compiled their own persuasive arguments for induction, including Dombrowski, Sabean, Theo Epstein, and Andrew Friedman.

“I think they’re both Hall of Famers,” says O’Dowd. Mariners GM Jerry Dipoto praises their “remarkable careers on opposite ends of the market spectrum” and echoes O’Dowd: “To me, both are Hall of Fame executives.” Beane, unprompted, endorses Cashman’s candidacy: “When everyone talks about the Hall of Fame, they name other people,” he says. “‘Oh, he’s won two championships, he’s for sure a Hall of Famer.’ They never say that about Brian, and he’s won four championships and has, I believe, the best record. It’s a slam dunk.” (According to MLB.com, Cashman’s lifetime .589 winning percentage entering this season ranked first among GMs whose careers started after 1950 and who amassed at least 10 seasons of service.) “It’s not just because the [Yankees] have a lot of money, because a lot of teams have a lot of money,” Beane says. “That’s not the reason. Brian is successful because he’s really, really good at what he does.”

It’s probably pointless to dwell on whether the right Cooperstown committee will one day find Beane or Cashman qualified for induction. A plaque would merely memorialize the accomplishments that already exist. Chief among their achievements is their staying power, which admits them to a more exclusive club than Cooperstown. Then there are the victories: Cashman’s Yankees and Beane’s A’s ranked first and sixth, respectively, in regular-season wins from 1998 to 2020.

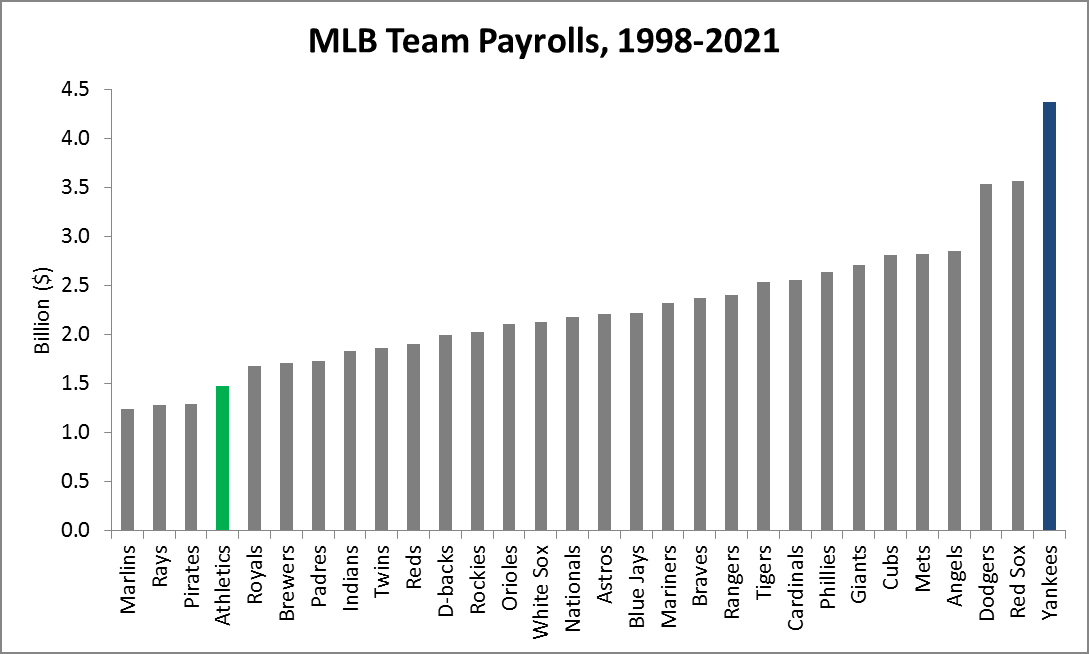

Remember the Moneyball movie quote about the A’s being below the rich teams, the poor teams, and 50 feet of crap? That line originated with Rachel Green, not Beane or Lewis, but it’s only a slight exaggeration. Cashman’s club, of course, is tops in cumulative payroll from 1998 through the present season, whereas Oakland sits fourth from the bottom. The most recent release of the annual Forbes franchise value rankings also finds the Yankees first at an estimated $5.25 billion. The A’s ranked fifth from the bottom at $1.125 billion—not much more than a 2014 FiveThirtyEight analysis suggested Beane had been worth to the team during his tenure.

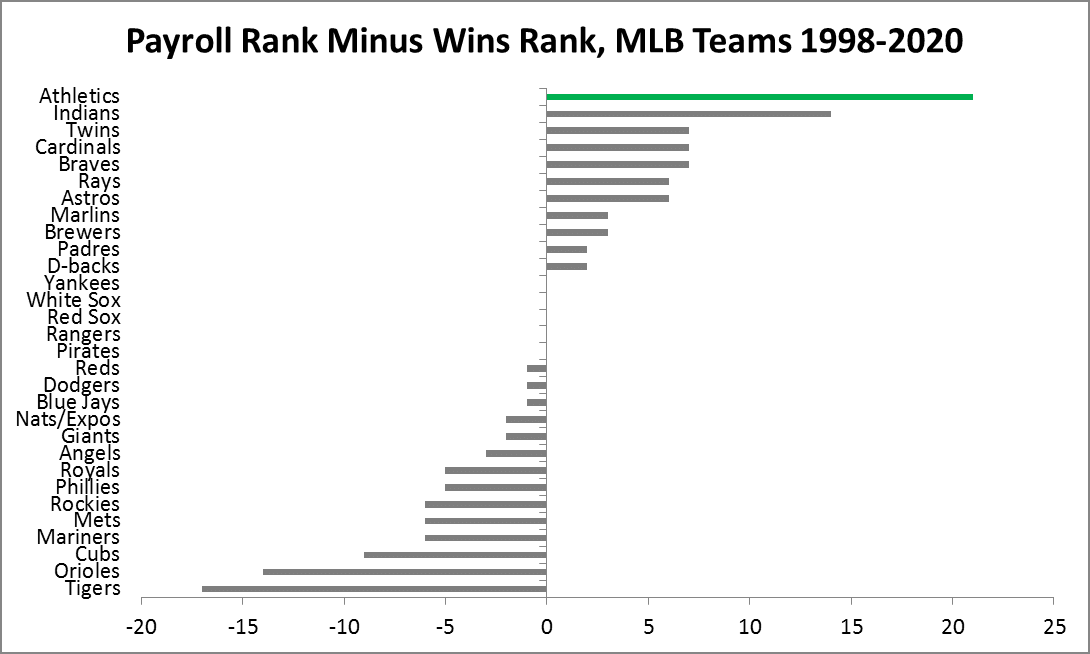

Merge those measures of success and spending by subtracting each team’s wins rank from its payroll rank—in Oakland’s case, six from 27—and you get the graph that accounts for Beane becoming a character in a bestselling book and an Oscar-nominated movie. The A’s have outstripped every other team in proving that payroll doesn’t dictate destiny, whereas the Yankees merely met the expectations that come with being baseball’s big-budget bullies.

There’s nothing inherently heroic about being cheap. A’s fans would prefer for the franchise to run a middle-of-the-pack payroll and win pennants, as the ’88-’90 teams did, than for ownership to shut its wallet year after year, which causes Beane to be celebrated for his ingenuity, but leads to the team missing the playoffs as often as not—and, in most of the good years, to falter in the first round. (Thus far, 2021 hasn’t been one of the good years; the A’s, who won the West last year but let several free agents leave and entered the season with a 1-in-3 chance to return to the playoffs, are off to a 4-7 start.)

But just as each marginal win is more valuable to a team on the verge of the playoffs, each dollar less devoted to a team that makes it to October amplifies the prestige of its architect. The Sporting News has handed out Executive of the Year Awards for 85 years, beginning with Branch Rickey in 1936. Beane has won three times (in 1999, 2012, and 2018). He trails only Weiss, who took home his four in the era of 16 teams. Cashman has yet to win one, even though he’s the only exec to earn four rings as GM since 1950s and ’60s Dodgers GM Buzzie Bavasi. Granted, Michael and Watson bequeathed Cashman the core that secured the first three titles of his tenure, but Cashman helped his predecessors craft those rosters, and he has a ’96 ring for his pinkie.

Beane and Cashman have been complimenting each other in print for almost as long as they’ve been running their respective teams. In 1999, after Oakland’s record poked back above .500, Cashman told the Daily News that Beane had done “a tremendous job under very different circumstances than what we get to work with. I don’t want to say ‘anybody’ could do it here, because what does that say about me? But here we get the best of everything that might give us a competitive advantage.” Two years later, Beane told the Hartford Courant that Cashman’s “weakness” was that he didn’t get the proper credit, adding, “I think he could be successful in any market, with any level of resources.”

I think Billy enjoys the intellectual game or exercise of thinking, ‘If I had these kinds of resources, these are the kinds of moves that I would make.’Farhan Zaidi

Many sources I spoke to speculated about how the two rivals’ legacies would be different if their situations had been reversed. Beane, at least, may allow himself to wonder what it would be like to get the go-ahead to re-sign a Jason Giambi instead of signing a Scott Hatteberg, even though Beane backed out of a big-market windfall with the Red Sox in 2002 because of his Bay Area roots. “I think Billy enjoys the intellectual game or exercise of thinking, ‘If I had these kinds of resources, these are the kinds of moves that I would make,’” says Zaidi, who believes Beane would handle the small-market-to-large-market transition as well as Zaidi’s old boss with the Dodgers, Andrew Friedman. “I think he enjoys playing armchair quarterback with some of the GMs with bigger payrolls.”

Cashman acknowledges that the spotlight on the Yankees, and the size of the organization, make it harder for him to pivot and innovate. “It’s definitely easier for a smaller market to be more creative and cutting edge on things, and experiment,” he says. But he claims not to crave any small-market cred. “I wouldn’t say there’s envy,” he says. “There’s more awareness and understanding that Billy’s pressure points are different than my pressure points.” More money means more urgency and less time to rebuild without winning, Cashman continues, but “either way, we’re all still trying to climb the same mountain.” Money helps establish a base camp from which to mount repeated assaults on the summit, but it’s no guarantee of planting a flag, as evidenced by the Yankees’ failure to win a World Series since 2009. If and when the Yankees win again, Lewis won’t be tempted to write a sequel about the big-market club on the other end of the “unfair game” in Moneyball’s subtitle. “That book is just less interesting,” Lewis says. “The Goliath story is a hard story to make swing on the page.”

By making Oakland’s David story swing, Lewis helped accelerate a transformation that was already underway. “In many ways, Billy (along with Sandy in the early years) and the A’s created the model for modern baseball front offices, especially in the realm of player evaluation and acquisition,” Dipoto says. That model, embraced first by small-market teams that lacked the luxury of competing for free-agent stars, enabled the early adopters to get more bang for fewer bucks. But wealthier teams were paying attention, especially after Moneyball lifted the lid. Cashman’s team was one of them.

Watching the A’s operate, Cashman says, “opened my eyes to a different process that we didn’t have, a different way to look at talent and evaluate talent. My argument with George Steinbrenner was, ‘The Yankees should be using every tool in the toolbox.’ And in that particular case, we weren’t. … The Moneyball era certainly cast a light on a deficiency, and my job is to shore up all deficiencies, all the time.”

Cashman rectified that deficiency in 2005 when he hired math whiz Michael Fishman, an insurance company actuary who had already interviewed with the A’s. Oakland was looking for an analyst to replace Beane’s top lieutenant Paul DePodesta, who had left to take a new job as the Dodgers’ GM. Amid Moneyball mania, the A’s sifted through thousands of applications and talked to the most promising candidates. Fishman finished second to Zaidi in the competitive process. Beane offered to serve as a reference for the runner-up, and when the actuary caught Cashman’s eye, Cashman called Beane, whose wholehearted endorsement helped seal the deal.

The Moneyball era certainly cast a light on a deficiency, and my job is to shore up all deficiencies, all the time.Cashman

At the time, the office was still populated by some old-school scouting types. Will Kuntz, who joined the Yankees as an intern in 2004 and rose to manager of pro scouting before departing in 2014, remembers, “They either didn’t care what Fish had to say, or they would just be like, ‘Hey, what’s 575 divided by 19?’ And Fish would answer in a second and a half, and then [they would] type in the calculator and be like, ‘That is amazing!’ And Fish was so quiet then. But Cash would come and say, like, ‘What do you think?’”

Fishman says, “I felt like from day one that he listened to me and he’d give me important tasks. … He always had my back from the beginning.” Cashman shielded Fishman from much of the internal resistance, put him in charge of a new R&D department, and later promoted him to his current role as assistant GM, in which he handles some of the same tasks that Cashman did under Watson—the circle of front-office life.

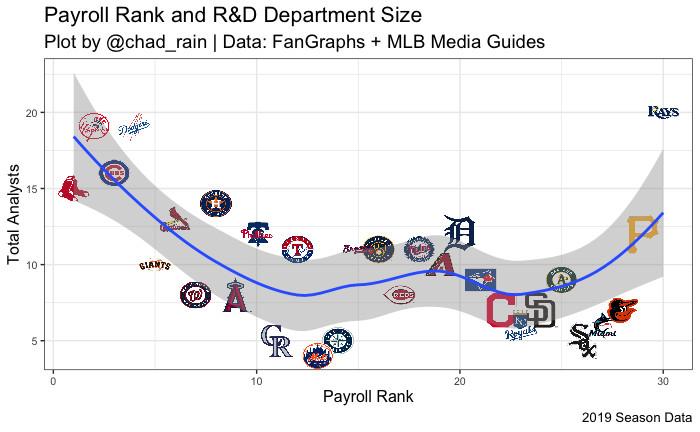

Under Fishman, the quant count climbed rapidly. According to a 2019 survey of MLB media guides, the Yankees boasted 19 full-time R&D employees, which tied them with the Dodgers for second most behind the Rays’ 20. The A’s, with nine, had fallen into a tie for 17th. “One thing I am proud about is transitioning the Yankees from maybe a more old-school, traditional style of thinking, and evolving the franchise into a more forward-thinking approach,” Cashman says. In the process, the Yankees lapped the A’s front-office investments just as they had earlier lapped them in player payroll. And the Yankees sank more money into off-field resources as the Oakland-led revolution in player evaluation gave way to a new revolution in player development that was led in large part by deep-pocketed teams like the Yankees, Dodgers, and Astros.

Beane used to tease Cashman about envying Oakland’s efficiency: “I’d kind of kid him that his dream was really to run the A’s,” he says. “He just wanted to run the Yankees like the A’s.” Now that the Yankees have come closer to resembling a version of the A’s that can also swim in the expensive part of the player pool, the two teams match up in trade talks less often. “When the game really started to change, when guys like Brian Cashman who are really smart guys who had a lot of capital started valuing the same things we did, then this type of trade was harder to make,” Beane says. “Those natural fits don’t exist as much anymore, because we’re all viewing the game in a very similar way.”

Those natural fits don’t exist as much anymore, because we’re all viewing the game in a very similar way.Billy Beane

Even though Beane has been baseball’s most prolific trader, the Yankees and A’s have made only five trades since Cashman replaced Watson, and three since 2003. The latter-day Yankees, Beane says, are “just smart in so many areas, but then when they want to put the big foot down, they can, i.e. Gerrit Cole. It was like, ‘We want him. He’s ours.’ Then it’s very, very challenging to beat them consistently.” In other words, these Yankees can still sign Giambi, but they might beat Beane to Hatteberg, too. The combination of brainpower and big budgets (“Moneyball with money,” as DePodesta put it) fueled the rise of superteams, which rack up wins against teams that are tanking—something both Cashman and Beane insist their markets won’t permit. Unlike the Rays, the A’s haven’t kept pace in the analyst brain race—arguably a missed opportunity, given the returns teams have reaped from those modest expenditures. Maybe the A’s should have hired Zaidi and Fishman.

Beane saying “Somehow we both survived” is about as satisfying as Poe Dameron saying, “Somehow Palpatine returned.” There has to be an explanation for something that seems impossible. Not only have they eluded the ax and declined to leave willingly for far longer than anyone else since World War II, but they’ve weathered the factors that seemed to make it less likely that they’d last. In Beane’s case, multiple ownership changes, impatience prompted by inevitable ebbs and under-the-radar rebuilds, a 55-year-old ballpark, and the uncertain geographical and financial future of the franchise itself; in Cashman’s case, starting out under Steinbrenner and confronting the unsatisfiable standards, nonstop scrutiny, and unwelcome tabloid attention of New York.

Their strategies for dealing with these dangers are different, to a degree: Beane and Cashman are compatible, but unlike Palpatine, they aren’t clones. For one thing, they differ when it comes to interests and ambitions beyond baseball. “It’s never occurred to me that he has another chapter that he wants to write that’s different from this one,” Beane says about Cashman. “I think he just wants to keep beating the hell out of everybody as the Yankees’ GM for as long as he possibly can. He doesn’t talk about the next phase of his professional life. I mean, I might say, ‘Hey, it’d be kind of cool to run Arsenal Football Club’ or something. Brian, no way.”

Cashman doesn’t dispute that. “I’m wired differently,” he says. “I’m wired in a way that, whatever I’m involved with, I’m doing the best I can while I’m doing it, rather than daydreaming about, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to do something else?’ To me, that’s wasted energy.” He studies other sports to see whether there’s something the San Antonio Spurs, New Zealand All Blacks, or Kentucky Wildcats do that the Yankees can use, but he doesn’t want to run any of them.

Also wasted, in Cashman’s mind, is energy spent on leisure activities. “I do have a hard time letting go,” he says. “I’m not, in theory, a vacation guy.” Over the years, his mind has been boggled by former GMs who took time off in-season; who actually—the horror—went away. “In New York, you couldn’t get away with that,” he says. “If I wasn’t present, I’d be destroyed. That way of life doesn’t exist in the New York Yankee arena. I was taught that way, I was brought up that way, and I’m conditioned that way.” The Boss has been dead for more than a decade, and it’s been more than 15 years since Cashman consolidated control of a front office that was divided between a Bronx coterie of Cashman loyalists and a backbiting Tampa contingent of Steinbrenner enablers. But it’s seemingly too late for him to drop his guard against the angry calls that have long since stopped coming.

Even Cashman’s charitable endeavors sound exhausting; to promote causes he supports, he’s rappelled down the sides of big buildings and jumped out of planes (sometimes with painful consequences). Aside from seeing his kids, Cashman says, “starting my day with a good cup of coffee is my vacation.” All the better because he can work harder when the caffeine hits. “More importantly, past all that, if the Yankees win, that’s my reprieve,” he says. “That’s my relaxation.” At least until tomorrow.

One would think that 35 years of such stress would take a toll, and perhaps it has. Working in baseball can be hard on relationships, and both Beane and Cashman have been divorced. But Cashman maintains that he’s energized by being graded every day, however harshly. “At no point have I ever noted any fatigue,” Beane says. “He literally is still revving at the highest level, which is incredible. I can’t imagine him ever taking a sabbatical. … I know how much he loves that job and he loves working for the Yankees, and he puts just as much into the job now as he did from the first time we talked about Kenny Rogers.”

He puts just as much into the job now as he did from the first time we talked about Kenny Rogers.Beane

A GM on his first call with Cashman could be forgiven for thinking that the veteran has forgotten more about the job than the greenhorn will ever know. In truth, he hasn’t forgotten much. Cashman keeps receipts. “He’s got a memory like an elephant,” Beane says. “A lot of it’s because he literally writes down every word you say, and he’ll bring it back to you, like, ‘Oh, you said this in ’07 about this guy.’” Cashman confirms that too. “I’ll try to write everything down to the best of my ability, so I get a sense from how people negotiate if they contradict themselves as they’re negotiating, whether it’s with an agent or a club on a trade,” he says. “All of a sudden, somebody’s packaging a player to me like, ‘This guy’s tough as nails, he’d be great in New York.’ But what he told me maybe a year earlier, ‘This guy’s so soft,’ just in terms of casual conversation. I’m like, ‘Well, you told me he was soft. I know you don’t like this player, and you told me he couldn’t play in New York. Now you’re trying to get me to trade for him.’”

Beane is committed, but less tethered to his desk. He takes trips. He fly-fishes. He accepts speaking engagements and owns pieces of two soccer clubs. He cares about baseball, too, but, Lewis says, “I think Billy could have taken it or left it years ago. … The idea that someone who really doesn’t need the job is breaking this record, maybe that’s a quality you need.”

Then again, Beane’s casual air is sometimes deceptive. Zaidi remembers the scene leading up to one of the biggest trades of his time in Oakland. Beane called his advisers in and asked to go over a few details before a call with his counterpart that was five minutes away. “The clock is ticking, four minutes, three minutes, and he’s asking questions like, ‘Hey, is this pitcher left-handed or right-handed? Is this the second baseman or the right fielder?’” Zaidi says. “And I just remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, we’re going to wind up trading for like three guys we’ve never heard of.’ Sure enough, once he got on the phone with this other GM, he was rattling off facts and stats about these players that I didn’t even know. The ability to answer the bell when it rings, it’s really unlike anybody that I’ve been around.”

In reflections from those who’ve worked with, competed against, or covered Cashman and Beane, the same adjectives resurface. Empowering. Competitive. Personable. Funny. Fearless. Egoless. Loyal. Honest. And maybe most often of all, adaptable.

Per Moneyball, the first rule Beane set for himself at the 2002 trade deadline was, “No matter how successful you are, change is always good.” On the surface, it seems as if the Yankees’ and Athletics’ front-office stability has defied that dictum, but their entrenched top execs have updated their outlooks as the sport’s meta has made old implementations of Moneyball outmoded. “They both have a completely adaptable mindset,” O’Dowd says. “And I think that’s allowed them to conquer the shelf life of these jobs versus most mortal humans. You don’t survive that long and succeed in the jobs the way they have unless you’ve created a culture inside your organization where you’ve empowered a ton of people to help you do the work, without letting your ego get in the way of them doing the work. And I think those two guys have done that exceptionally well.”

Zaidi, Forst, Fishman, and Kuntz all express similar sentiments. “I think [Beane] has a vision of the type of thinkers that he wants himself surrounded by,” says Zaidi, who was one of them. “I think he feels pretty strongly about hiring people that he knows are better than him.” As Kuntz puts it, “Cash is like, ‘Let me find people who are smarter than me and get a piece of that.’”

In that respect, Beane and Cashman are completely in lockstep. “I’m aware that I’m not the smartest person in this operation,” Cashman says. “I can open my mind up to help and be willing to ask for it and know that it’s there when necessary.” Former Angels GM Billy Eppler, who worked for Cashman from 2005 to 2014, says, “He approached those relationships with such an open-mindedness that you felt like, if you had something important, then you could change his mind.”

J.T. Stotts is the rare crossover character who has worked for both Beane and Cashman in multiple capacities. The 41-year-old former minor league infielder played in the two teams’ farm systems, then worked as an A’s area scout for nine years before joining the Yankees as a pro scout in 2015. The budget divide was eye-opening. “Evaluating players, I have to adjust and say, ‘All right, this is the Yankees,’” he says. “You’re picking from different pools. … If we like the guy, we might spend the money and go out and get him.” When Stotts, who was used to strict room-rate restrictions from his years with the A’s, booked a Days Inn, the Yankees’ pro scouting director questioned his taste in hotels. “He goes, ‘You stay at those?’ And I was like, ‘Sure, why not?’ He’s like, ‘Yeah, you don’t have to stay there when you’re working for us.’”

Despite the swankier accommodations, the tone at the top was the same. “Pulling a lot of different people’s inputs and then making his own decision off of that, that’s where I think Cashman and [Beane] are very similar,” Stotts says. “Because they have people they trust, but in the end, they’re pulling a lot of different sources to come up with the ultimate decision.” As support staffs swell and databases expand exponentially, hiring, delegating, and synthesizing several sources of information have become a GM’s most indispensable skills.

By the largely lily-white, male-skewed historical (and present) standards of MLB front offices, both Beane and Cashman have hired and promoted a significant number of employees from diverse backgrounds to prominent positions, including Kim Ng, Jean Afterman, Kuntz, and Rachel Balkovec in the Yankees’ case and Zaidi, Billy Owens, Eric Kubota, Haley Alvarez, and Justine Siegal in Oakland’s. “Diversity and reflecting the community has been something that has been very important to [the A’s],” says Susan Slusser, who covered the team for the San Francisco Chronicle from 1999 to 2020. Zaidi, a Canada-born, Philippines-raised Muslim of Pakistani descent who was hired without any previous baseball experience, says, “You see more diversity of thought in the groups that they’ve put together,” possibly because Beane and Cashman predate the intellectual arms race that centers on poaching employees of leading teams and “makes the industry a little more insular and less diverse in thought or background.”

That unorthodox structure inspires esprit de corps. “We have a culture that Billy has established over 20-plus years because people trust him and believe in him, because he is who he is,” Forst says. “Not because he’s the Moneyball guy, not because he’s brilliant, but because he has the ability to make you feel important, to make you feel a part of what the A’s are doing.” Some aspects of that decentralized culture could outlive their creator, but for now, at least, all roads lead back to Billy. “There’s not a formal process to a lot we do,” Forst says. “It’s Billy’s inquisitive mind that raises these topics, and then we either run with them or we decide, maybe that’s not for us.”

Similarly, all lines of communication in the sprawling Yankees organization are oriented toward Cashman, a far cry from the days when Steinbrenner’s creative torments included banishing the GM from the area behind home plate where he stood with Beane before the 2018 wild-card game. Cashman isn’t as hot-tempered as Beane used to be, but he doesn’t just speak softly and carry a big payroll. Former Rangers and Brewers GM Doug Melvin, who’s 68, remembers both Beane and Cashman being uncowed by the company at their early GM meetings. “They both were not afraid to speak up,” he says.

Cashman has stood up to Steinbrenner, refused to defer to Derek Jeter and Jorge Posada, and, in a relatable lapse into anti-A-Rod anger, snapped, “Alex should just shut the fuck up.” (He regretted that last outburst, though few others begrudged him the thought.) Cashman, Beane says, is “self-assured, and I think he’s humble at the same time.” Hence the quote that Kuntz, who’s now the assistant GM of MLS club LAFC, calls the top takeaway from Cashman that he’s carried to his current role. “He was just like, ‘Just don’t forget, we are all whale shit on the bottom of the ocean,’” Kuntz says. “‘This game was around before us, and this game will be around way after we’re all dead. We’re whale shit on the bottom of the ocean.’”

Cashman’s stance on vacations makes him sound scary, but whatever psychic wounds from the Boss he still bears haven’t turned him into his own petty tyrant. “When I first came over here, I was, ‘OK, I’m going to the Yankees,’ buttoned-up and shaved,” says Stotts. “I thought it was going to be more of a serious atmosphere.” Then he discovered the Cashman who doesn’t typically appear at press conferences—the prankster with the infamous fart machine. “He’s like a big kid, and he likes to joke a lot and keep the room loose,” Stotts says. The same goes for Beane, who in 1986 said he’d always go by Billy because “In baseball, you’re always a big kid anyway.” Kuntz speculates that Cashman’s sometimes-sophomoric humor helped him cope with Steinbrenner’s tantrums. “He found his way to keep from losing his mind.”

Beane has found a way to keep from losing his temper. “There’s a ferocity to Billy that the cool California kid masks,” Lewis says, adding, “If you back Billy Beane into a corner, you better watch out. You just wouldn’t want to do it.”

Before the approach to player evaluation and in-game tactics that Beane helped popularize became baseball’s new dogma, his agenda depended on pairing soft power with an imposing presence. “There really wasn’t a player in the Oakland clubhouse, or a coach or a manager, who wasn’t pretty sure Billy Beane would kick his ass if they got in a fight,” Lewis says. “I said, ‘You’re using violence to impose reason. You’re using everybody’s fear of you to make them be reasonable.’” Beane agreed with his observation. But Beane is far less explosive in his silver-fox stage, now that reason is the rule, not a rarity. Who on the A’s would want or dare to back Beane into a corner in 2021? “He really has mellowed out to a pretty good degree,” Slusser says. “To the point where now he’s kind of like, ‘Wait, I’ve never yelled at you.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, only about 700 times, but sure, not recently.’”

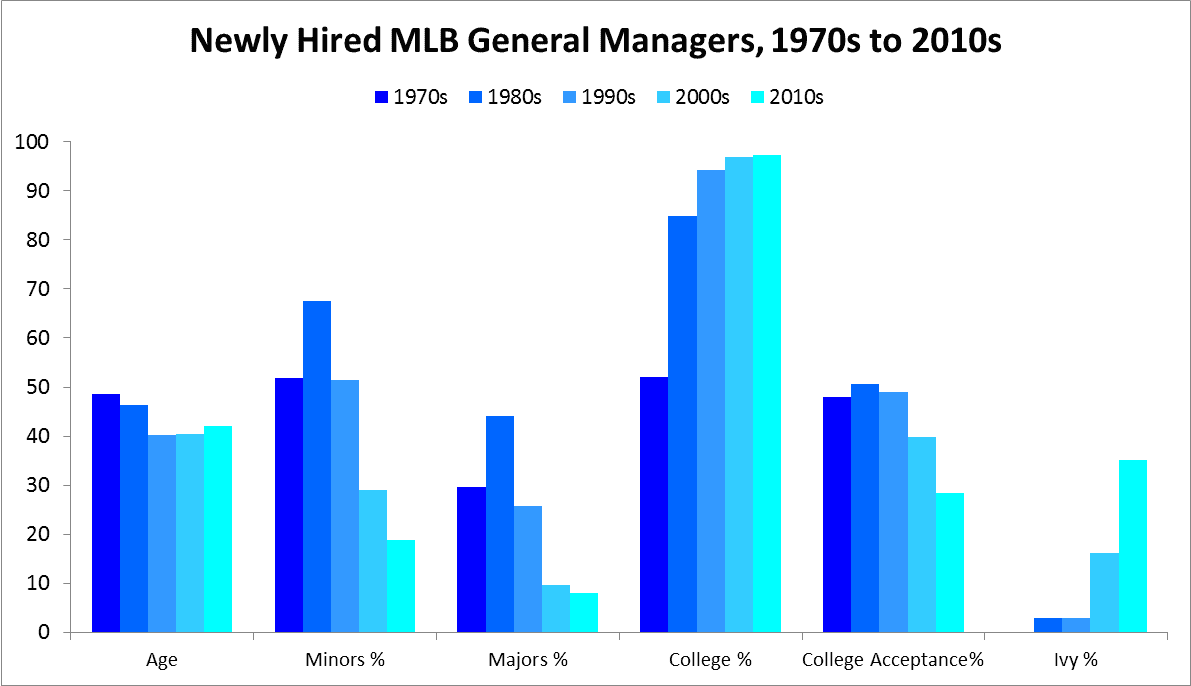

As the angry young man mellowed and aged, the GM ranks reshaped themselves. The Wall Street types who flocked to the Moneyball banner may not have shared the physiques or backgrounds of Beane, but they joined him in genuflecting at the altar of “assets” and “efficiency.” Compared to decades ago, newly hired GMs are much more likely to have college degrees, and it’s also much more likely for those degrees to be from Ivies or other exclusive schools. Although the Phillies and Rangers hired stat-savvy former major leaguers Sam Fuld and Chris Young as GMs over the winter, other former pro players beyond Beane and Dipoto are few and far between. So are non-quants like Cashman, who graduated from Catholic University with a history degree. “I don’t think I’d qualify for an internship today,” the possible future Hall of Famer says.

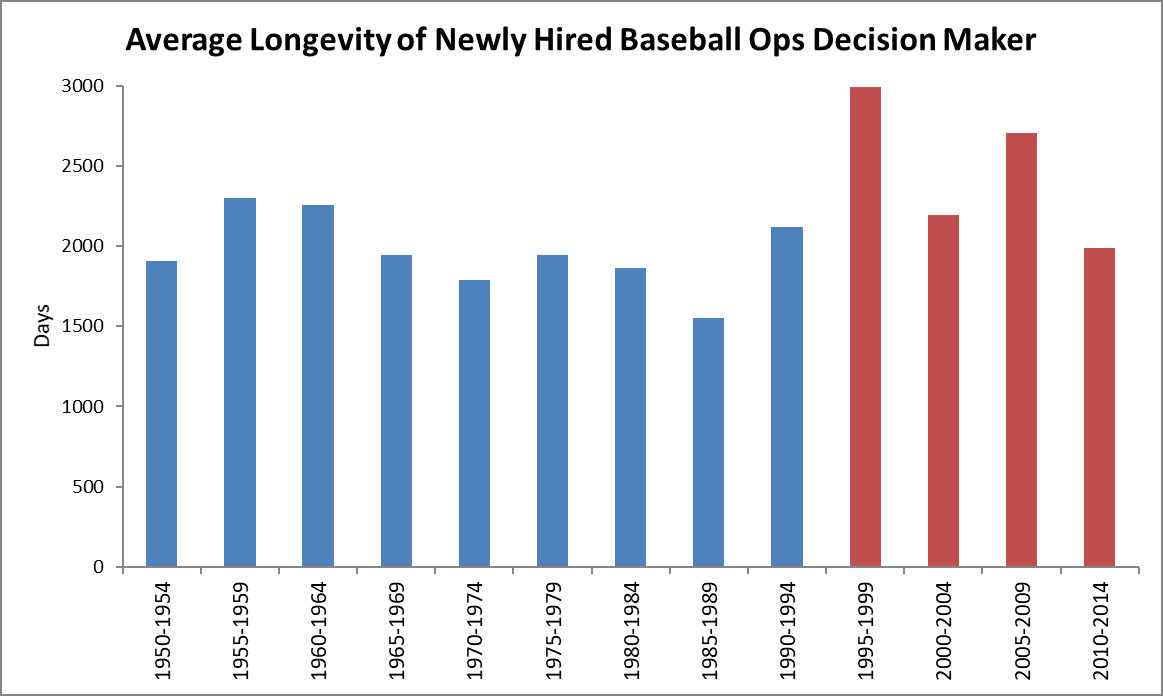

One by-product of that demographic shift is that baseball ops decision-makers—not just GMs, but also senior officials like Beane who have more inflated titles—are lasting longer than before (albeit nowhere near as long, on average, as Beane and Cashman, who are still skewing the professional life expectancy of the 1995-99 cohort of hires). The bars in blue below are frozen; the bars in red, which encompass some active executives, are rising by the day.

Owners are likely more aligned with business-minded modern GMs than they were with the grizzled baseball lifers who headed front offices before. They’re also increasingly less liable to fire someone with a sound process based on bad luck—especially because teams tend to turn profits and appreciate whether they win or not. Plus, as Lewis says, “The bum running the place is now famous.” Beane and Cashman have helped usher in the era of the well-compensated celebrity GM who doesn’t defer to dugout middle managers. “If you’re the owner who selected this person and paid him lots of money, it’s like a first-round draft pick,” Lewis says. “You give him lots and lots of opportunities to fail, because you’ve said you think he’s the right guy, and everybody’s noticed that decision.” Cashman made $300,000 in his first season as GM. He’s making $5 million now.

Part of the reason Beane can be fearless, Lewis suggests, is that he’s so secure. “There’s a kind of efficiency, if you’re owning one of these places, to making your general manager feel secure so he doesn’t do things for reasons of appearance,” Lewis says. “That he does things for reasons of substance.” There’s also something to be said for the wisdom that comes from having seen some (whale) shit. “No matter when you got into the game or how intellectually flexible you think you are, you’re always going to have some inertia to the body of knowledge that you had when you first started doing this work,” Zaidi says. “With a lot of the innovations that came along during my time with the A’s, I think Billy was more progressive and interested in pushing the envelope than even I was at time. That probably comes with the perspective of seeing the game work through so many cycles. Whereas some of us more recent arrivals probably thought that we were arriving with the truth and maybe not recognizing how constantly evolving the job really is.”

Maybe it’s just the cyclical lament of a GM generation that senses its influence ebbing, but some of Beane and Cashman’s contemporaries speak about the two friends and periodic opponents as if they’re Adams and Jefferson, the last links to bygone days of bold, decisive action. “The game is missing guys like this,” Ricciardi says. “Both of these guys have personalities, and both these guys aren’t afraid to make a deal. They have a lot of old-school in them. … I think they carry the torch for the guys who may have been around long enough to realize how this was done in the past.” You either die a revolutionary or live long enough to be old-school.

The game is missing guys like this. Both of these guys have personalities, and both these guys aren’t afraid to make a deal.Ricciardi

The younger GMs will get older also, and someday, someone will call them old-school. But maybe they won’t be old friends. “I think there’s a sense of ruthlessness that didn’t exist when Billy and Cash were the young upstarts in the game,” says O’Dowd. If that’s true, it could be because the newly minted GMs aren’t engaging in the group activities that Melvin remembers. “We didn’t shy away from getting together and going out and having drinks together, having dinner together, staying up late at night together,” he says. “We used to go play basketball together.”

Even prior to the pandemic, much of that had changed. “Brian and Billy’s relationship is a little bit of a product of a bygone era,” says Forst, 44. “I would consider myself close to a number of other general managers around the game, but the communication is different. … We text a lot. It’s possible to do entire deals over texts at this point. There just isn’t the same face-to-face interaction that there was 10, 15, and certainly 20 years ago.”

In trade talks, the medium is the message—these days, Cashman is a master of GIFs—so a lack of face time affects how GMs conduct their delicate (and often indelicate) dance. Lewis wrote in Moneyball that “It is the nature of being the general manager of a baseball team that you have to remain on familiar terms with people you are continually trying to screw.” Beane and Cashman are experts on the screwing who also excel at the schmoozing. “Both are among my favorites to deal with,” says Dipoto, who deals with almost everyone. “It’s straightforward from the start, and you know very quickly how far the discussion will go.”

Beane can be a hard seller, as Melvin found out when Beane tried to entice him into trading for one A’s player. “He was selling him so much to me that I almost asked, ‘Why are you trading him?’” Melvin says. O’Dowd remembers Beane badgering him leading up to a 2001 trade for Jermaine Dye. “He was all over me about trading Neifi Pérez to the Royals [for Dye], and ‘I’ll give you a hell of a package for Jermaine Dye.’ Well, he gave me a hell of a package, all right. Not one guy could play in the whole group.” O’Dowd got Beane back in the 2008 Carlos González–Matt Holliday trade, and he got his goat in 2012 by sending Marco Scutaro to San Francisco instead of Oakland. “He got the ass at me, man,” O’Dowd says. “He was pissed. And so it was that kind of relationship where I told him, basically, ‘You can go kiss my butt, Billy.’”

Reclusive A’s owner John Fisher has addressed the media only once since purchasing the team in 2005, and Yankees managing general partner Hal Steinbrenner is nowhere near as vocal or visible as his father. The franchises once owned and defined by legendary loudmouths Charlie Finley and George Steinbrenner, and associated with stars from Rickey to Reggie, have now been branded by Billy and Brian, the former fifth outfielder and the uplifted intern.

Earth’s north and south magnetic poles migrate every year. Cashman and Beane, the deployers of the sport’s antipodal payrolls, never have, but even they will one day. “No one really retires as a GM,” says Ricciardi, who was fired as Blue Jays GM in 2009. “Usually you’re asked to leave.” Beane’s and Cashman’s current contracts run through 2022; Beane has a rolling arrangement in which he informs the A’s at the end of each year whether he wants to tack on another. Both are in the uncommon position of choosing whether to stay or walk away. “The longer they’re there, the less likely they are to be dislodged, because everybody knows they’re good at the job,” Lewis says.

Last year, Beane flirted with leaving voluntarily, prompting premature paeans. In October, the Wall Street Journal reported that Fenway Sports Group planned to merge with RedBall Acquisition Corp., a special-purpose acquisition company that Beane cochairs. If the transaction had been completed, Beane would have had a financial interest in the Red Sox, so he likely would have had to leave the A’s. That could have been the beginning of a second career as a sports-business mogul. Instead, the deal was scuttled, and Beane stayed put. “I suspect he was inching out the door with the RedBall thing,” says Slusser. “And I think he’s probably, if not this year, then probably very soon, at least considering exploring other things.” Beane may relish red paper-clipping his resource-starved team to the postseason, but being forced to make borderline-embarrassing offers or talk a tightfisted owner out of stiffing minor leaguers as the A’s adjust to a loss of revenue-sharing funds probably isn’t as stimulating.

“I can’t imagine Billy’s going to do the job that much longer,” says O’Dowd. Yet Forst, who views Beane’s out-of-the-box thinking and his own linear thinking as a useful yin and yang, counters, “I can’t imagine doing this job without Billy next to me. So it’s certainly not something that I’m hoping for or looking forward to at any point.”

Long as Cashman and Beane have been doing their jobs, neither is inured to defeat. Even though Cashman’s teams have strung together the most consecutive winning seasons since the Yankees of Barrow and Weiss, he hasn’t forgotten the feeling; in his first four seasons working full time for the Yankees, only Cleveland lost more games. “I don’t think he would think of himself as having started with a dynasty,” Kuntz says. “I think he would think of himself as starting in the late ’80s. He’s thinking about Danny Tartabull and Roberto Kelly and Andy Stankiewicz and Matt Nokes. He’s not thinking of Jeter and [Andy] Pettitte and those guys. He was there for them, too, but he was forged in a different fire.”

Cashman, who probably considers co-chairing a SPAC another waste of energy, got a guarantee in 2019 from Steinbrenner’s elder son Hank, who said, “As long as I’m a general partner of this team, Brian Cashman will be the general manager.” Hank died seven months later, but the surviving Steinbrenner children may also feel beholden to their dad’s former whipping boy. Cashman, like Beane, is a master mollifier of owners, which is perhaps the most useful self-preservation skill a sports exec can have. But tact is no substitute for a title. “Whether you’re strategic about when to say something or not to say something, that’s not going to matter,” says Cashman. “It’s not going to save you if you can’t win.”