Bob Odenkirk was worried about the bus scene.

It was the second week of shooting for Nobody. He’d been training for two years, undergoing the painstaking (and often painful) work of becoming the sort of actor who believably looks like he could take down multiple adversaries. A bunch of quieter scenes were in the can—now it was time for the first big action sequence. Here it was: Bob Odenkirk was about to beat the crap out of a bus full of people.

“We had a star that was willing to put in all this hard work and prep like crazy for such a long time. I think the only person who was worried about the action was Bob,” remembers the movie’s director, Ilya Naishuller. “Because I knew it was going to be great.”

Odenkirk says the scene was his way of “planting our flag and saying this is what we’re doing here. We’re going to make an action film, and we’re going to try to live up to being as gritty as they can be. And if we don’t pull that off, then we haven’t gone to where we were aiming for. So it was everything. It was two and a half years of training I was risking.”

Naishuller and his crew shot the lead-in scenes where Odenkirk’s character, the frustrated working stiff Hutch Mansell, walks onto the bus and stews silently as a bunch of intoxicated Russian thugs enter and harass everyone. They shot the scene where the bus door closes after Hutch tells everyone but the thugs to vacate. They shot the scene where Hutch tells the thugs he’s about to fuck them up. And then it was time. “Bob is just, ‘OK, let’s do this,’” says Naishuller. From there, all hell—or at least, all carefully choreographed hell—broke loose as the man known as Saul Goodman proceeded to put a bunch of Russian thugs half his age in the hospital.

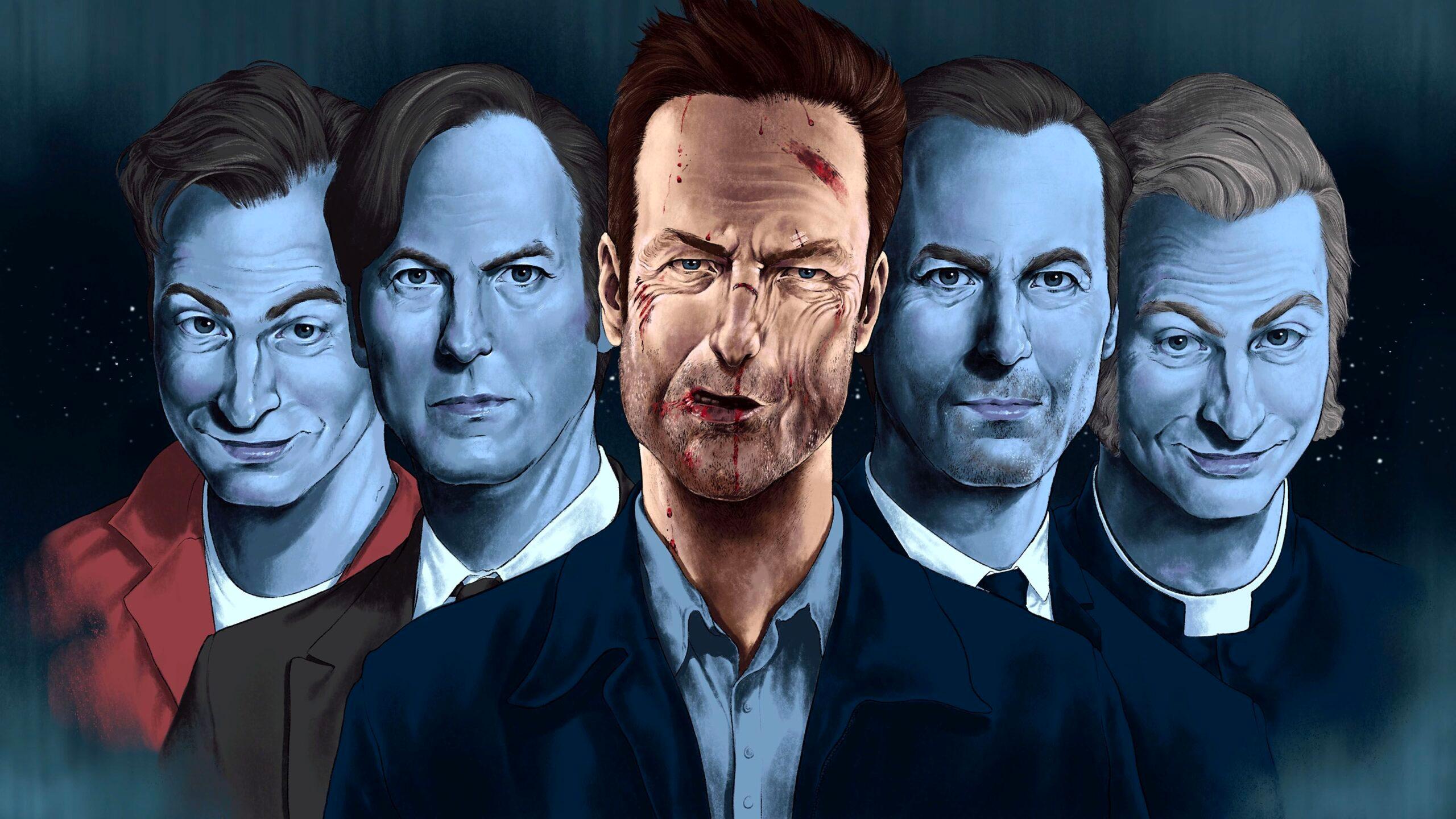

Odenkirk got his start writing for Saturday Night Live, and his ’90s HBO deconstructionist sketch comedy series Mr. Show made him an alt-comedy icon. His performance as criminal attorney Saul Goodman on Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul showed a dramatic range that surprised even his most devoted fans, and now it’s not at all uncommon to see him pop up in Oscar-nominated films like The Post. But for a performer who’s now just shy of 60 years old, Nobody was a specific challenge. The bus scene was all the confirmation Odenkirk needed that everything was working. On most nights of the Nobody shoot, Naishuller and Odenkirk would exchange emails, analyzing the day’s work and where the story was going. Most of Odenkirk’s emails “were usually pretty long, because he’s the writer,” Naishuller says. “And I just came back and wrote the shortest email I’ve ever done in my life. I wrote, ‘Bob, You’re A Fucking Action Star, Goodnight.’”

There’s a pretty good chance you’ve seen David Leitch take a punch in a movie. He was one of Brad Pitt’s go-to stunt doubles, working on Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Fight Club, and Ocean’s Eleven. He also did stunt work for The Bourne Ultimatum, 300, and even Corky Romano before he began coordinating action scenes for films such as TRON: Legacy. Then, after two decades of working as a stuntman, stunt coordinator and second-unit director, he and his friend and fellow stunt expert Chad Stahelski decided to show the world what they can really do. Filmed on a small budget and released in 2014, the pair’s directorial debut, John Wick, became a word-of-mouth hit. And thanks to its revolutionary, borderline operatic action sequences and deadpan (emphasis on dead) humor, John Wick eventually earned a reputation as the most influential action film of the 2010s.

With the John Wick series, Leitch had a hand in one of vanishingly few successful film franchises that’s not a reboot, superhero film or based on a preexisting intellectual property. His success with Deadpool 2 and the Fast & Furious spinoff Hobbs & Shaw gave him further leeway with the studios, he says, and he’s taking advantage of it. “I’m super, super grateful,” he says. “We’ve been given those opportunities and thank God, because, looking at the big tent poles out there, it’s hard to find anything that you’re not reinventing from someone else’s thing.”

I just came back and wrote the shortest email I’ve ever done in my life. I wrote, ‘Bob, You’re A Fucking Action Star, Goodnight.’Ilya Naishuller

Stahelski would direct the Wick sequels by himself while Leitch and his wife Kelly McCormick started the production company 87Eleven Productions to inject the Wick ethos (i.e., character-driven plots, ridiculous action that’s taken very seriously) into the entire action genre. In 2017, after Leitch had directed Charlize Theron in the Cold War–action film Atomic Blonde, Odenkirk came to them with a pitch. He wanted to tell a story about a mild-mannered family man whose home is invaded by thieves. When given the opportunity to defend his family, he demurs, and the resulting shame and taunts from his father-in-law, played by Michael Ironside (“I’m thinking you did the best thing you could. I mean, you being you.”), leads him down a path of truly gnarly violence. If you wanted to describe the resulting film as Cinnabon Gene Loses His Shit and Murks Some Dudes, you wouldn’t be too far off.

“It was Bob’s idea. He had an incident at his home and he kind of wished that he would have handled it differently,” says McCormick. “And I said to him when he pitched it to us that ‘I think you might have handled it well, if this is the way you wanted to handle it. Let’s just leave this for fiction.’”

She elaborated via Zoom that Odenkirk and his family were the victim of two home invasions, “and one of them was really kind of insane.” Odenkirk’s children are of similar ages to the kids in Nobody, and the vulnerability he felt as a father inspired his idea for the story, based around how he reacted, and more importantly, the fantasy of how he could have reacted.

The advent of Bob Odenkirk, Fucking Action Star, is a thrilling and pleasing turn of events. It’s also quite an unexpected one. He understands why you might be surprised by all this. It’s not what he would have predicted back when he was doing Mr. Show. “I made fun of action movies,” he says. “In fact, David Cross and I once hosted an event at the Olympia Film Festival where all we did was watch a Steven Seagal movie and make fun of it on microphones.”

But Odenkirk never turned up his nose at the action genre. He appreciated the greats like Death Wish and the works of John Woo and Jackie Chan’s Police Story films. He also understood the genre enough to suspect he might be able to bring a vulnerability that could potentially prove both rare and exciting. “There were things I felt like I could do in this world. I knew I could train, and that would be interesting and challenging. And I thought I could deliver the intensity,” says Odenkirk. “And I thought I could really do that thing that films this genre often tries to do, which is to say, ‘here’s a character who you don’t expect to be capable of anything physical and then surprise people with their skills.”

Ever a man of discerning taste, Odenkirk went straight to the best. “He wanted our action,” says McCormick. “And so he kind of put the whole thing together.” McCormick and Leitch were huge fans of Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul, and his comedy work. They were also aware he wasn’t an action star, but that’s what made the idea of working with him exciting. “We were looking for that challenge,” says Leitch. “We were fans first, but then it was also like, ‘how do we take this person who doesn’t seem like the muscle-on-muscle action star, and shock the audience with their skills?”

McCormick and Leitch recruited Derek Kolstad, the creator and screenwriter of the John Wick Cinematic Universe, to write the Nobody script, and hooked Odenkirk up with Daniel Bernhardt, a martial artist and actor. (Since the Venn diagram of Barry fans and Better Call Saul fans is two quarters stacked on top of each other, it’s worth pointing out that Bernhardt plays the martial artist who Barry reluctantly has to kill in the classic episode “ronny/lily.”)

But they cautioned Odenkirk that these things take time. And in true Hollywood shifting chairs fashion, the movie bounced around distributors for a while before finding a home. After STX Entertainment backed out in 2019, McCormick and Leitch started a partnership with Universal Pictures called 87North Productions. Universal wanted Nobody to be the first film they made together. But even as all those pieces were coming together, Odenkirk was getting ready.

“He was obsessed about training, he trained for two years,” McCormick says. “He trained before we had a script. At one point we were like, ‘Bob are you sure you want to keep training? We might not get this one set up!’”

With a good foundation to work from—McCormick calls Odenkirk “an obsessive runner”—Bernhardt began training him in martial arts and how to convincingly handle guns and other weapons. “The hardest part was the embarrassment of sucking for so long, and especially sucking when you’re standing right next to Daniel Bernhardt, the best in the world at screen fighting,” says Odenkirk, circling his torso to demonstrate the jabs and throws he began learning. “And there I am next to him trying to duplicate his moves and failing miserably for so long. It was a year and a half into my training when he finally said, ‘OK, you can slow down your moves now for the camera.’”

The training was as much about adding muscle as it was teaching Odenkirk how to follow fight choreography. “Making sure you lead with your hips and getting your feet in the right position,” Odenkirk says, moving both arms to his right side like a cardio teacher. “It’s a hell of a workout.”

I knew I could train, and that would be interesting and challenging. And I thought I could deliver the intensity.Bob Odenkirk

Fight scenes and dance sequences are almost the same thing to Leitch, and he plans his battles down to the second. “We were designing a style and we’re choreographing bits to learn and repeat. And at the same time, he’ll learn some practical martial arts as well,” say Leitch. “But a lot of it is like, how to do fight choreography. So it’s not necessarily about stepping out of the gym and being able to defend yourself in real life. And he was as ready as any actor that we’ve ever had.”

In all of his movies, Leitch tailors the fights to the nature of his characters. The fighting style they landed on in Nobody portrays Hutch as tough, but not superhuman like John Wick. He’s not a sure thing, you see him struggling. He relies on a lot of elbow and knee shots to take down bigger foes, as well as the use of found objects, what Leitch calls “force multipliers.” The ending builds to what McCormick calls a “Rube Goldberg”–style conclusion, as Hutch sets up a series of bombs and traps (including literal mousetraps) to stop the Russian gangsters he ends up pissing off, while still giving and taking a lot of blows. A lot of blows.

“He gets hurt a lot, which is a part of it,” McCormick says. “That helps show a weakness that then you then overcome. You get stronger.”

Revealing character through action is raison d’être of McCormick and Leitch’s work, and the throughline for Nobody is the wish-fulfillment aspect of Hutch. “He’s such an everyman that can then actually take matters into his own hands and become a better father and a better protector of his family through this journey that he’s on,” McCormick says. “It wouldn’t have been the same journey if it would have been an expected sort of action guy.”

When the script was ready, it was sent to the Russian-born director Naishuller, who’s best known for making the 2015 action film Hardcore Henry, a film shot entirely in first-person, like an immensely violent first-person shooter video game. “My plan was always to be a more intelligent kind of filmmaker. And with Hardcore, that fell apart because I had such a great time. It was silly in all the right ways,” he says via Zoom. “I’m very proud of the movie with all its faults and all the successes, but I knew the next one I wanted to be fairly, fairly serious, while still being entertaining.”

Admitting that he did “have something to prove,” he told his agent that the next film he wanted to make was “an action film with a comedian in the lead, with a shotgun.” That was six months before he received the Nobody script. “Comedians are inherently dark,” says Naishuller. The director got what Nobody was going for—he understood the angry father part, but he saw an even deeper layer.

“Whether you guys know it or not,” he told Odenkirk, “it’s a film about a guy who was addicted to violence, who kept it bottled up. And the most interesting thing about this film is that there’s an inner conflict,” Naishuller says after taking a luxuriant pull off his vape. “It’s not just the hitman who’s coming back because someone took something of his. Hutch really, really wants to get back into it.”

Leitch and McCormick didn’t see Odenkirk for a while as he trained and they got the pieces put together. When he showed up on set in Winnipeg (chosen for its tax incentives and “Americana” feel, according to McCormick), on the outside he looked like Hutch—like an ordinary dude—but something had changed. “We said there isn’t going to be that shirt-off moment in Nobody,” Leitch remembers. “But you could have had it, because he was ripped. It was good for him to be able to internalize that physicality for the character.”

A hipster comedy god in his own right, Odenkirk nevertheless had a rule for himself: No Irony On Set: “I’m not being cheeky. I’m not making jokes. My character gets genuinely angry, which, you know, could be embarrassing if it comes across as fraudulent or pathetic.” He wasn’t going to be quippy or detached or make it seem like Bob Odenkirk Kicking Ass was a self-aware joke. He was going to commit completely. “One of the things I thought I could bring to this genre was I could continue to play the character even when I’m fighting,” he says. “You look in my eyes and you see doubt, uncertainty, pain, frailty that you don’t usually see in an action lead in the midst of a fight.”

McCormick calls Odenkirk “the Energizer Bunny” on set, always up for another take, always willing to do multiple run-throughs of a scene on a cold, rainy day in Winnipeg. The bus scene that had their star a bit intimidated occurs about a half an hour into the film, which is an eternity for most action films, but that delay was meant to both amplify audience tension and stretch the budget. Odenkirk became notably less nervous after he got over that hump, says Naishuller, and since the movie was largely shot chronologically, the viewer can see him become more confident as the film progresses. “We were fortunate that it was actually in story order. So it was working for his character, getting his mojo back,” say Leitch.

“You saw the rust come off. And then he’d do something, and there were just cheers everywhere,” McCormick adds. “A million times, it was like, ‘Yeah, Bob!’”

Nobody is a B movie that knows what it is and hits its marks; it pretends to be serious on the surface but ultimately revels in its absurdity. (Any film that uses a kitty cat bracelet as an excuse for the protagonist’s vengeance binge knows what it is.) It isn’t a grounded film, per se, but it’s grounded and progressive in its own way.

The film has a lived-in, tactile feel and a bit of a retro vibe (Hutch has quite an impressive vinyl collection and vibes out to Pat Benatar before going on a rampage), an inventive approach to violence (no spoilers, but the film offers a surprising amount of options to bludgeon one’s foes with), and largely but not completely sidesteps a number of the genre’s clichés. Naishuller says care was taken to avoid stereotypical Action Film Wife clichés with Connie Nielsen’s character and to humanize Aleksei Serebryakov’s Russian Drug Lord antagonist, who would prefer to spend his days dancing and singing karaoke at his nightclub (he’s a big Andy Williams fan) but feels obligated to kill Hutch after he messes up his little brother on the bus.

It’s all too early to say, but Odenkirk is ready if there’s a Nobody sequel (which is certainly set up by the end of the film), and he’d also love to do an action comedy along the lines of a Jackie Chan film. Even during the pandemic, he’s been staying busy with core and upper body work, with “some boxing or some jump rope in there,” and Bernhardt keeps sending him routines to memorize. Odenkirk is an action star now. He’s gotta stay ready.

The right kind of ridiculous, Nobody wouldn’t work without Odenkirk’s dedication. It also wouldn’t exist if he didn’t push it into existence as hard as he pushed himself. And part of the surprise of the Bob Odenkirk Kicks Ass Era is that it was hardly a foregone conclusion he’d be able to pull it off. The whole thing could have come across as a silly exercise in actorly vanity. Maybe not a career-ender, but an all-time embarrassment for sure. But it was precisely the threat that Nobody could have been a debacle for Odenkirk that made it exciting for him. “I don’t know why anybody goes to show biz to be safe. We go in to risk and try and very, very often fail,” he says. “And that’s part of it.”

He knows what it feels like to miss. He’s had pilots that didn’t get picked up and films that bombed. But back when he was bringing the word “taint” into the cultural lexicon, the man who cocreated Mr. Show didn’t exactly see himself one day sharing the screen with Meryl Streep either. To hear him tell it, he’s been taking swings since the start. He recalls one of his earliest performances in front of an audience, at an improv night at Chicago. “I remember getting really nervous, and then looking at myself in the mirror and saying, ‘Look, don’t do this if you don’t want to risk. Stop now. But if you want to do it, then you just have to compartmentalize this and go out there and suck.’”

Fortunately, Nobody does not suck. But a big reason why is because Odenkirk wasn’t afraid of that outcome. “You can’t do this without risking so this is a big risk in some ways and not a big risk in others,” he says. “And one I was willing to take.”

Michael Tedder is a freelance journalist who has written for Esquire, Stereogum and Playboy. He is currently working on a book about the Myspace music era for Chicago Review Press. He lives in Hoboken, New Jersey.