The Academy Award for Best Picture used to be easy to predict. Now it’s almost impossible.

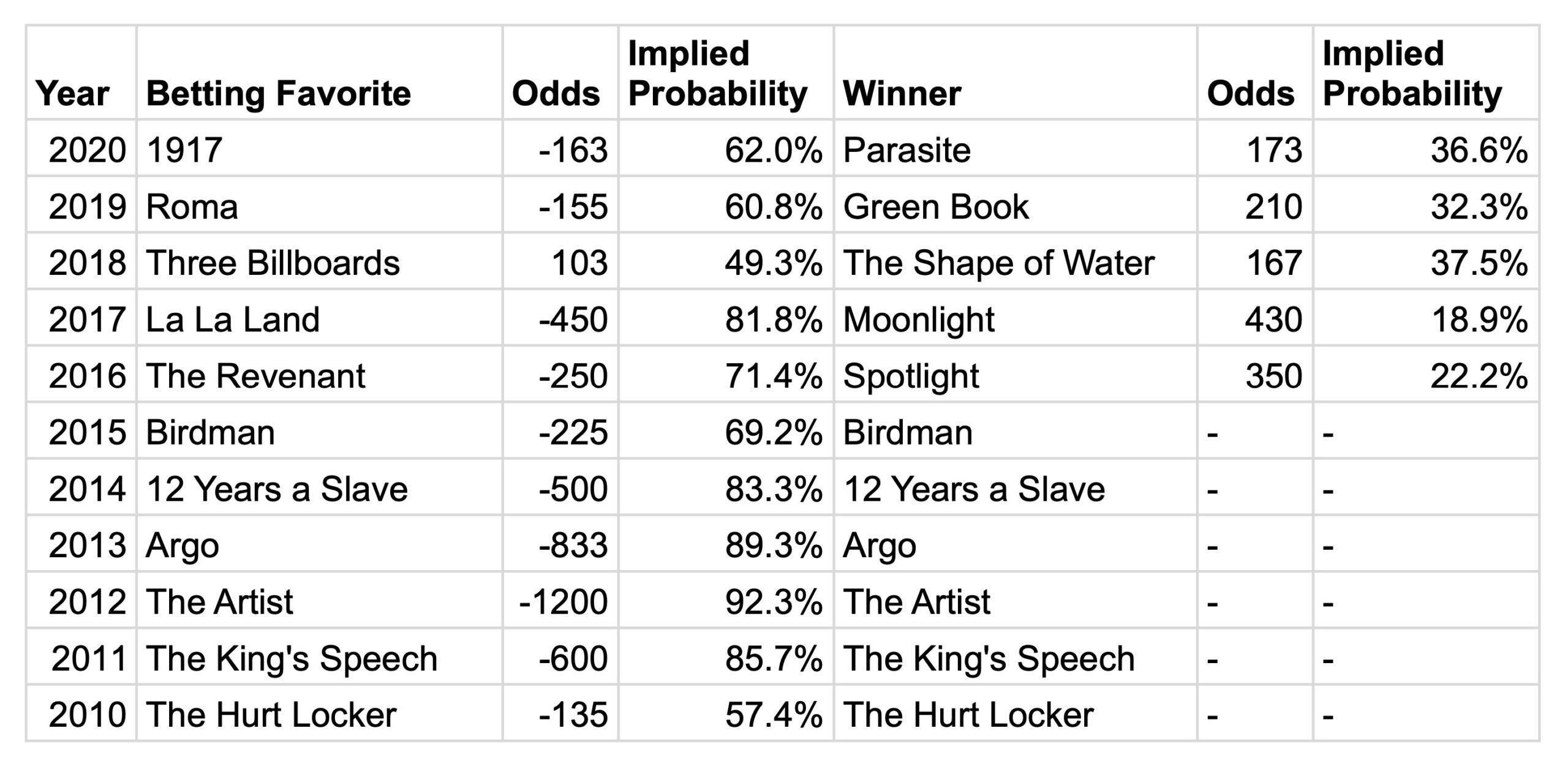

From 2001 through 2015, the betting favorite for the award going into the night ultimately came home victorious every year except 2005 (when Million Dollar Baby toppled The Aviator) and 2006 (when Crash upset Brokeback Mountain). But since 2016, there have been five straight upsets. That includes true shockers like Spotlight and Moonlight, modest upsets like The Shape of Water and Green Book, and last year’s delightful Parasite win.

I broke this trend down a year ago, just days before Parasite’s win over a field that included 1917, which came into the night as a solid favorite, with betting odds that implied a win probability of 62 percent. But Parasite, with a roughly 37 percent chance, broke through, continuing a mind-boggling run of Oscars upsets. Here’s what the past 11 ceremonies look like in a chart, with the betting favorite on the left and the ultimate winner on the right:

If you take these probabilities at face value, the chances of these five recent upsets all happening is a measly 0.2 percent. We don’t have reliable betting odds going back to the early days of Oscars ceremonies (this year marks the 93rd Academy Awards), but rest assured that nothing like this has ever happened in the modern history of the awards. It’s wild. And, most importantly, it’s made the race for Best Picture a ton of fun.

This year, Nomadland is the favorite, with minus-670 odds, per the Action Network. That implies an 87 percent chance of winning, making Nomadland the biggest favorite since Argo in 2013. The Trial of the Chicago 7 is the next film on the list, with plus-600 odds and a win probability of 14.3 percent (the numbers add up to more than 100 percent because the oddsmakers are taking a cut. If they added up to less than 100 percent, a bettor could go place wagers on every film and guarantee a profit). Those are longer odds than we’ve seen for second-favorite in quite some time, but the past half decade of Oscars ceremonies have held true to an old cliché: Expect the unexpected.

So why is the Oscars’ biggest race so volatile now? And is Nomadland truly set up for triumph, or just more failure? Let’s dig in once again.

How the Changing Academy Membership May Be Affecting the Oscars

It’s impossible to draw a straight line of causality and say that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science’s diversity push—inspired by 2016’s #OscarsSoWhite debacle—has changed the Oscars and the Best Picture race. While this year’s nominees are the most diverse in history, last year’s were as boring and homogenous as ever. More time will have to pass for anyone to say whether the Academy’s changes will consistently be reflected in its nominees and winners, but the Academy has changed—a lot.

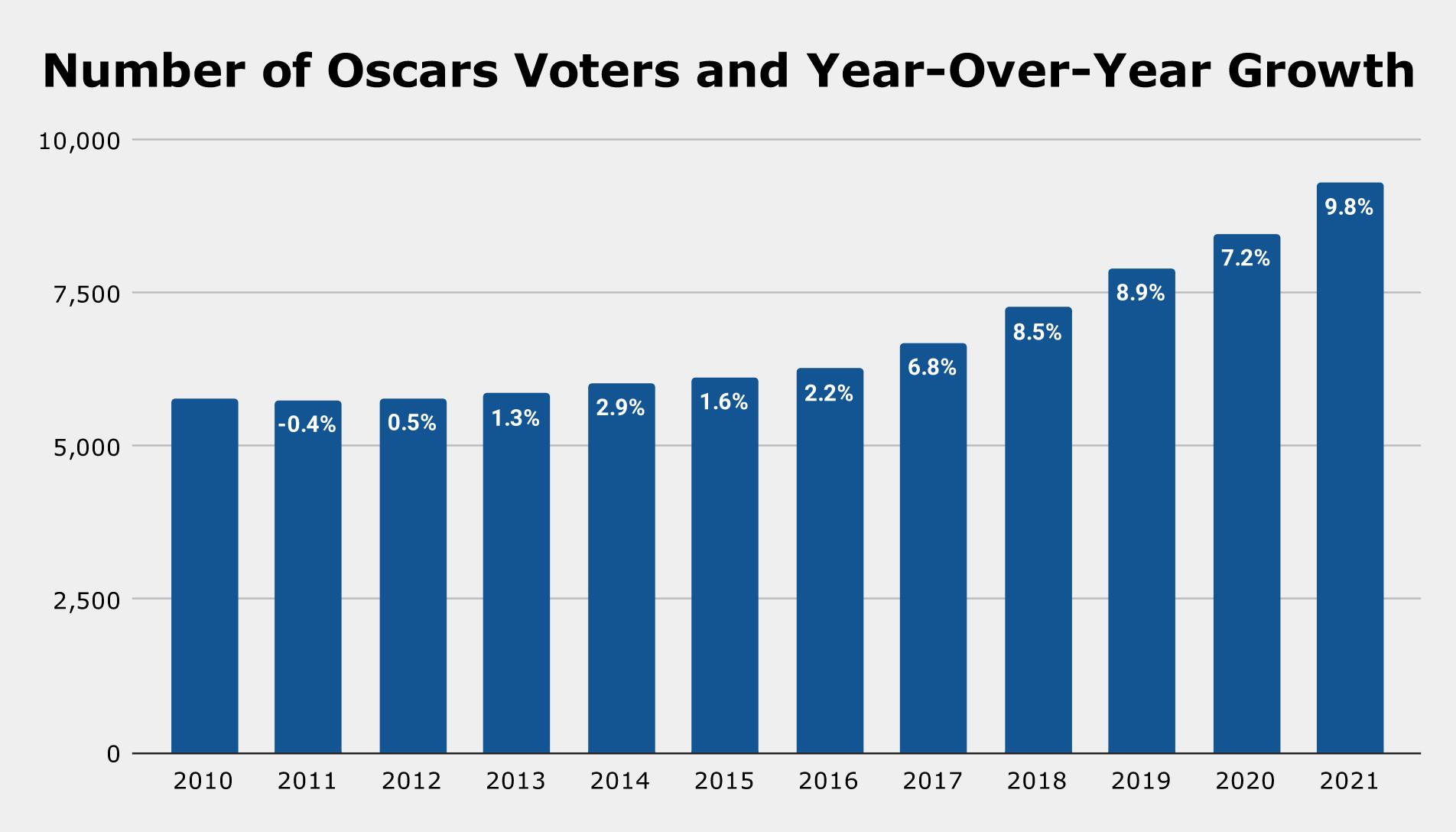

For decades, the Academy consistently hovered around 6,000 members, but that number has exploded since 2016. This year, 9,300 voters will decide who goes home with Oscar trophies.

Along with that growth, many Academy members retire or die every year, so the Academy as a whole looks dramatically different than it did just a decade ago. Walt Hickey estimates that a full half of voters in the Academy joined in 2012 or later.

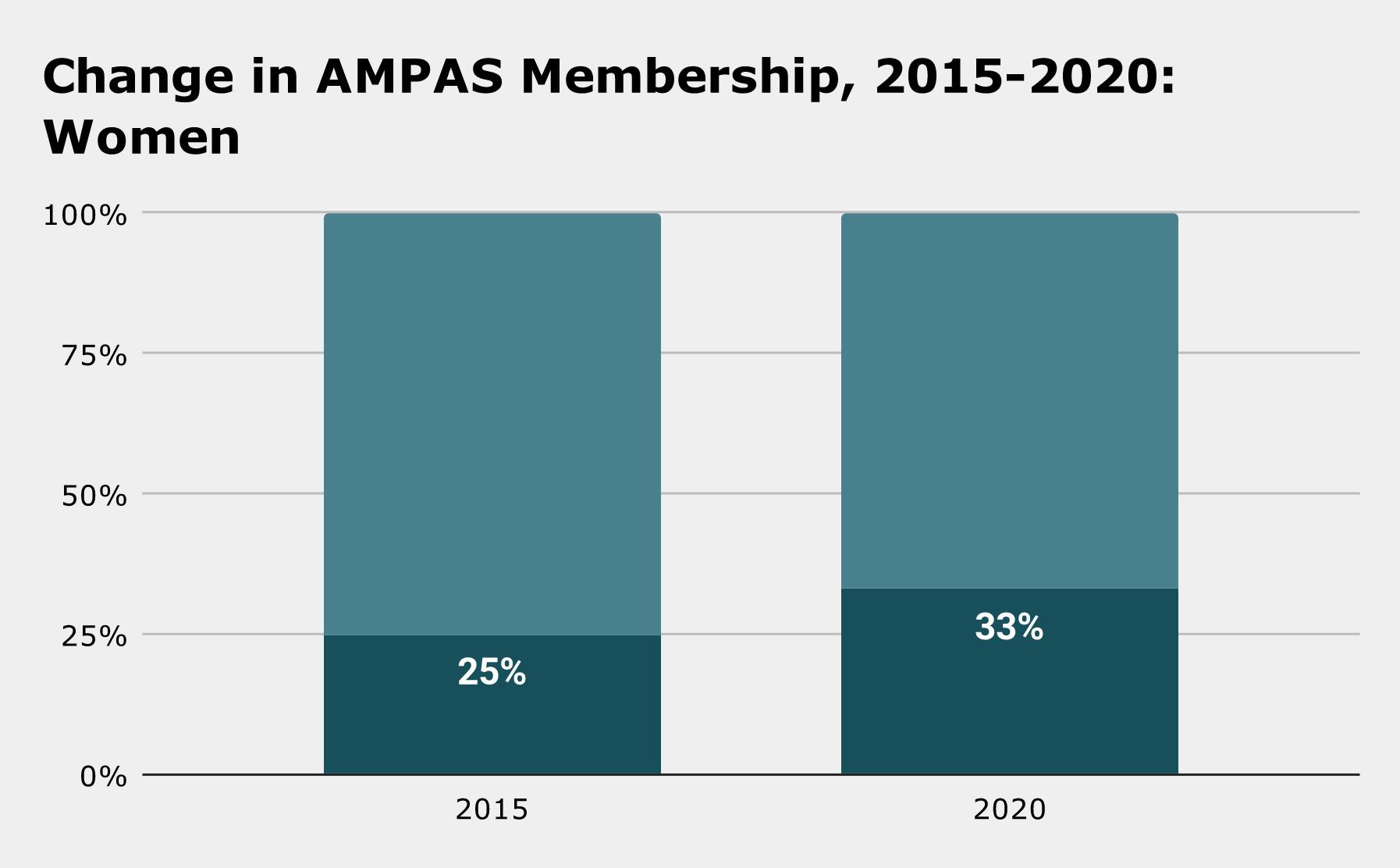

And diversity is improving, though perhaps not as much as the Academy would have you believe. In a 2020 press release, the Academy boasted that it doubled the number of female members and tripled the number of members that are from underrepresented ethnic or racial communities. But because the entire Academy has also grown at the same time, the growth of the voting share of those groups isn’t quite double or triple what it was in 2015. For example, women account for roughly a third of the Academy now, compared to 25 percent in 2015:

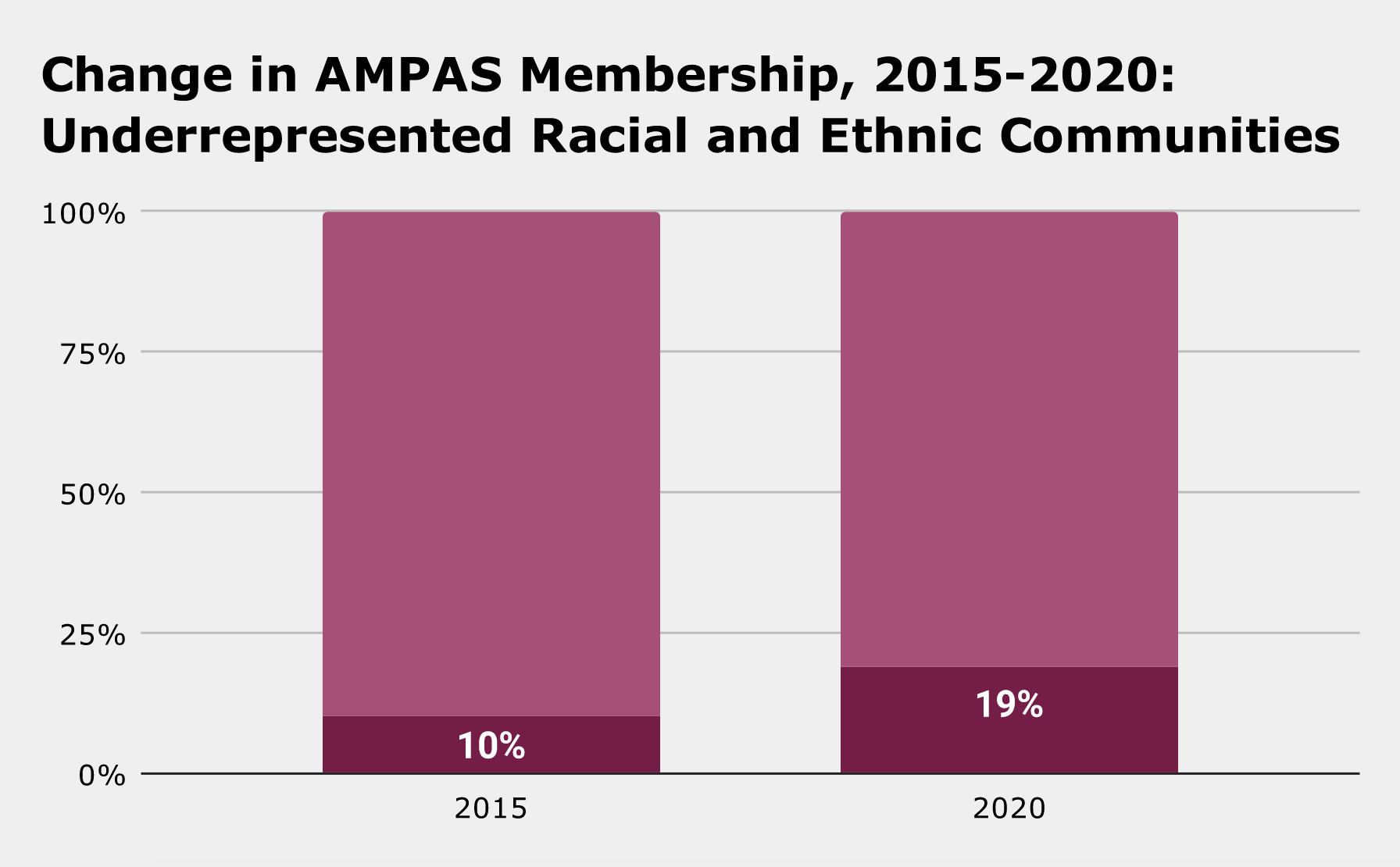

Underrepresented ethnic and racial groups nearly doubled their voting share, up to 19 percent from 10 percent:

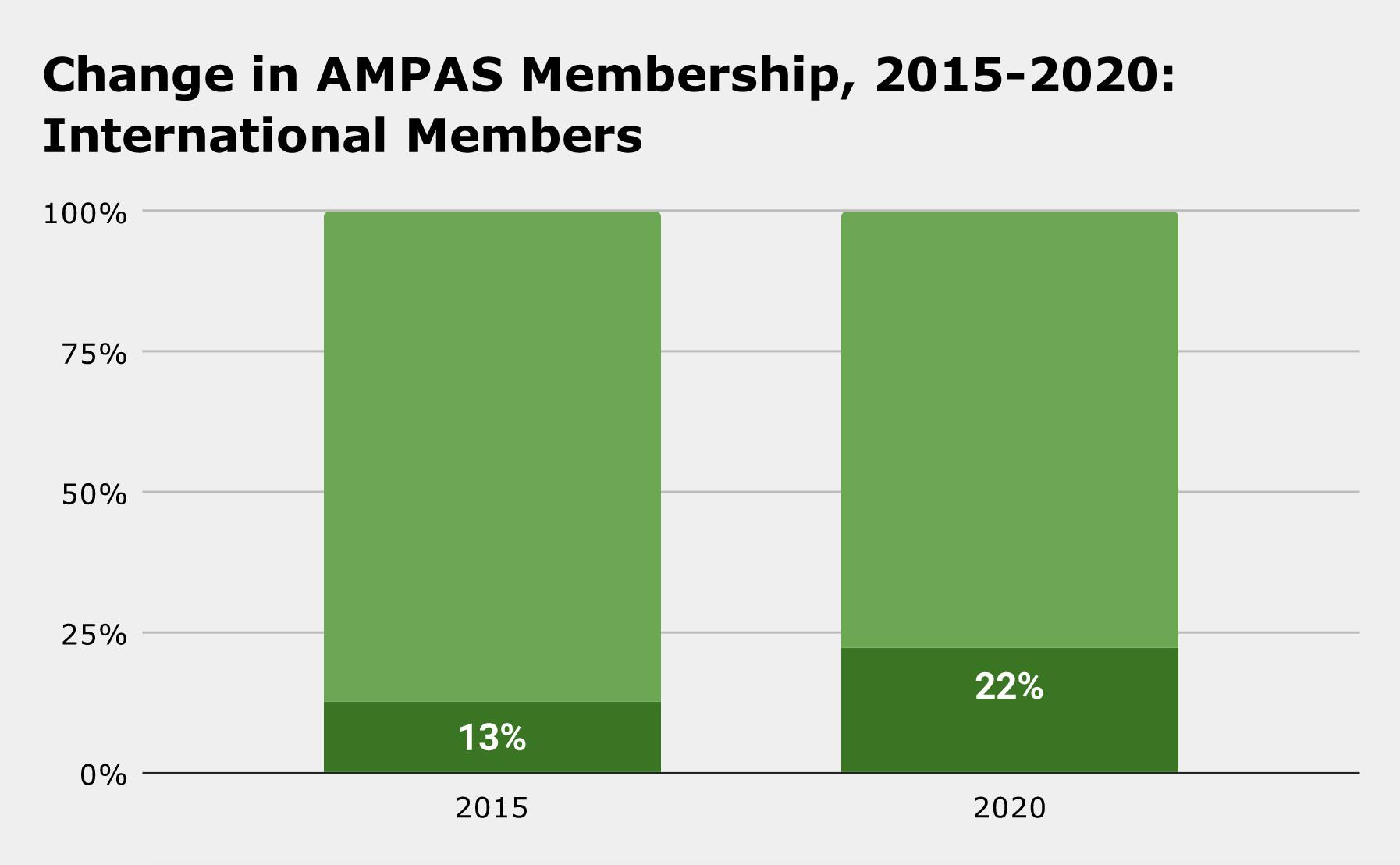

And because the Academy also shared the raw numbers of international members (now at 2,107, up from 724), we can also estimate the vote share of that group. As of 2020, international members account for roughly 22 percent of the Academy, up from 13 percent:

The Academy is still far whiter, far more male, and far older than the average population. And at the current rates they are adding women and minorities to the organization, it’ll never match the demographics of the country, much less the world. But given just how white, male, and old the Academy was in the past, the Academy’s recent efforts have marked a significant change.

Looking a little further back in history, the change in the Academy is even more pronounced. Hickey uncovered a press release from 2001 that implied that at that time, 74 percent of the Academy lived in just California. Given that only 78 percent of the Academy is from the States now, it’s assured that the number of California-based members has shrunk considerably.

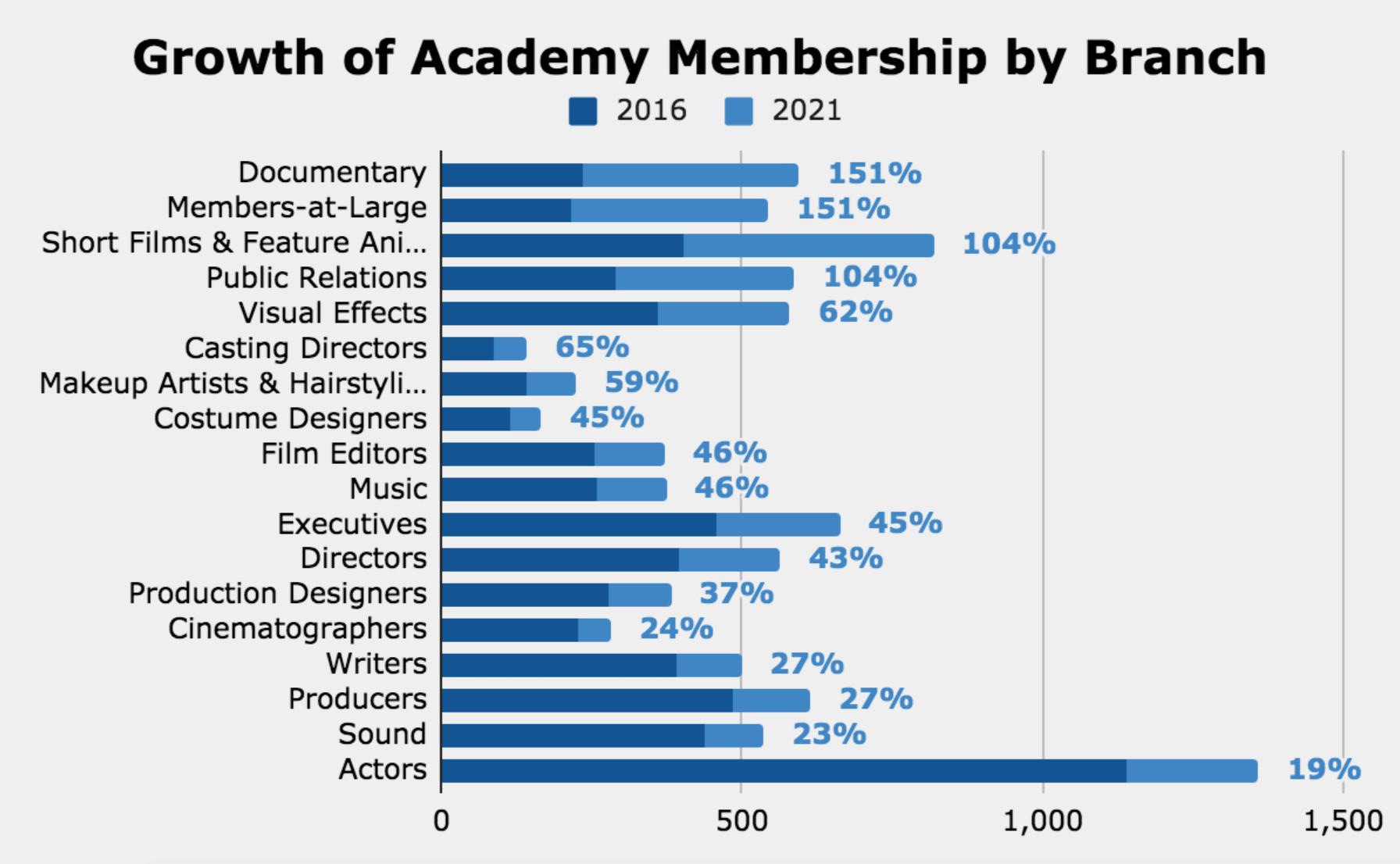

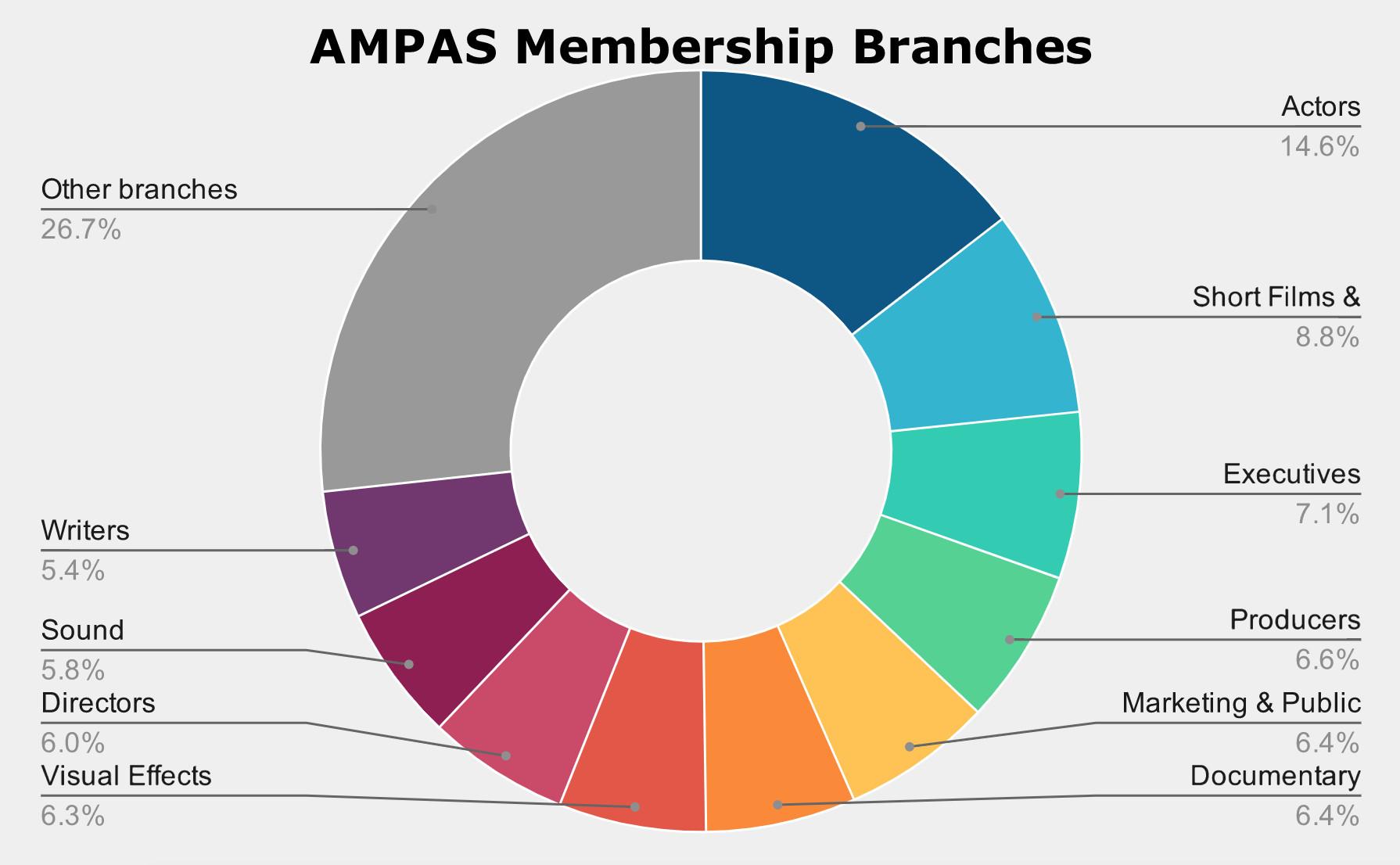

Going even deeper under the hood, the churn in new membership has also remade the sizes of the various branches of the Academy. Seventeen branches are eligible to vote for Academy Awards, plus a members-at-large group that isn’t technically a branch, but can also vote. Thanks to Steve Pond’s yearly tallying at The Wrap, we can see how the individual branches have grown in recent years. It’s that members-at-large group that has grown the most since 2016, boosted by a decision this past year to award agents the right to vote. The group that has grown the least percentage-wise is also the group that happens to be the largest and flashiest: actors.

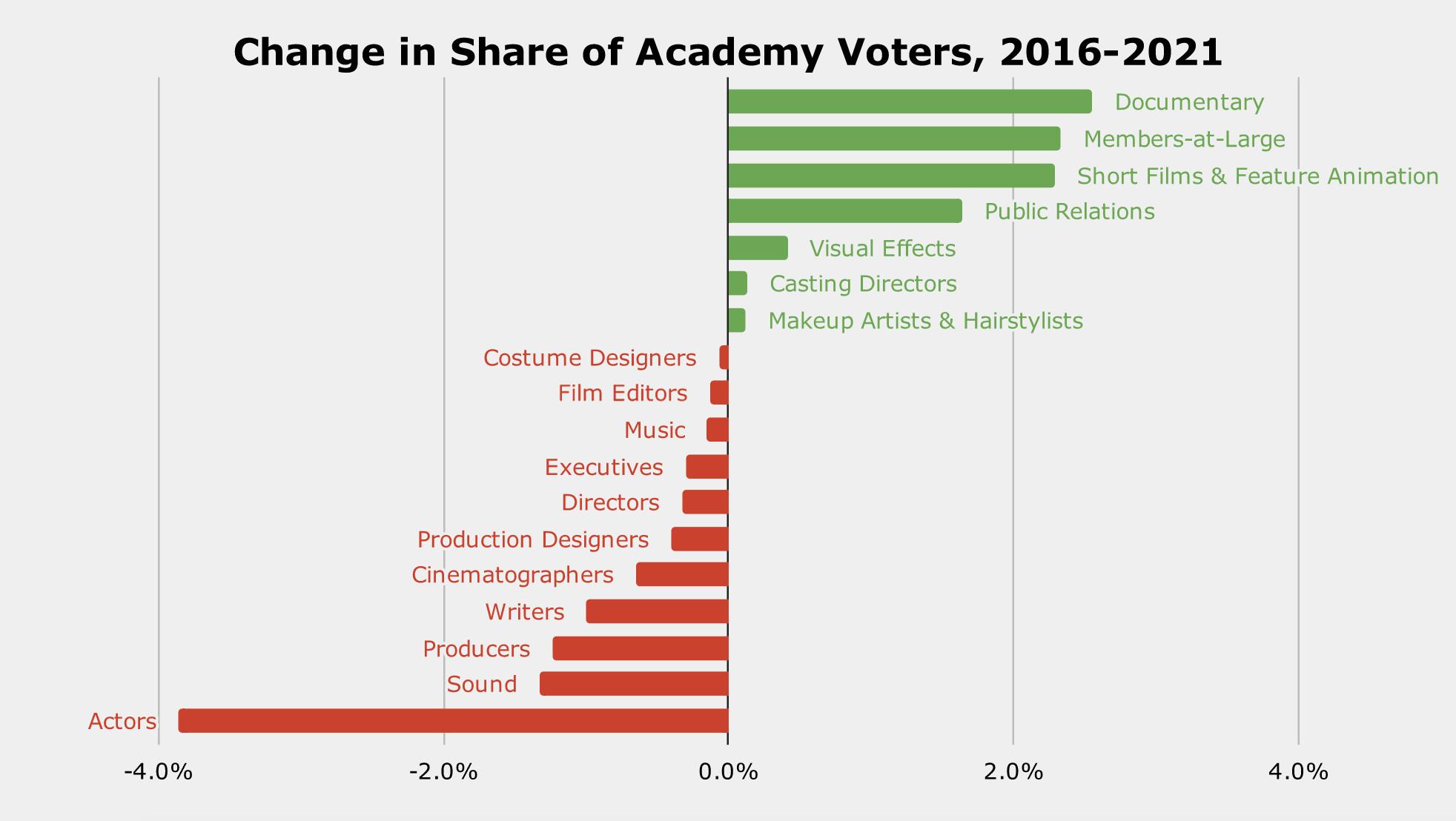

Typically, a film becomes a Best Picture favorite by winning at guild awards that precede the Oscars. That includes ceremonies held by the Producers Guild, Writers Guild, Directors Guild, and Screen Actors Guild—among many others. But those guilds roughly correlate with groups that are shrinking in influence within the Academy. Producers, writers, directors, and actors are all near the bottom of the above chart, and all grew by less than the 51 percent that the Academy overall has grown by. Those four groups together accounted for 39.1 percent of the Academy in 2016. Today they’re at 32.7 percent. That’s not a massive drop, but it helps explain why those big guild awards (which only share small overlap with the Academy anyway) don’t correlate with the Best Picture winner very much anymore.

Actors have fallen the most in voter share in the past five years, dropping from 18.5 percent of the Academy to 14.6 percent. Producers, directors, and writers all fell, too, along with sound designers, cinematographers, production designers, and a host of others. The groups that have seen the most gains are more obscure. The documentary branch has had the biggest gain in vote share, jumping from 3.8 percent of voters to 6.4 percent. The members-at-large and short films and feature animation groups are just behind—they round out the only three branches that grew by more than two percentage points.

The public relations branch grew by 1.6 percentage points (now making up 6.3 percent of the Academy’s votership), while no other group cracked half a percentage point. That the biggest adjustments come from groups that are less prominent could be contributing to all this Oscars volatility.

The Voting Process Itself Changed

For the 2010 ceremony, the Academy expanded the Best Picture nomination from five films to 10 (and two years later modified it to be a flexible number between five and 10). That was likely a response to The Dark Knight not being nominated the previous year, though the Academy has never formally admitted as much.

With more films in the running, the Academy reintroduced a preferential voting system that hadn’t been used since the 1940s. Unlike every other award, the movie that gets the most votes doesn’t simply win Best Picture. Instead, Academy voters rank all of the Best Picture nominees, and the Academy first counts up all the no. 1 choices. If no film has at least 50 percent of the first-place votes, the film with the lowest total of votes is dropped from the pool, and its votes are redistributed to the films that those voters picked as their second choice. This process repeats until one film has at least 50 percent of the votes.

With the preferential ballot, the Best Picture race should theoretically favor films with broader appeal over more divisive pictures that benefit from a passionate fan base but leave others less enthusiastic. That’s a big change, but it’s also one that didn’t seem to affect the predictability of the Oscars for the first six years after it was introduced, as the odds-on favorite to win the award won every time. But since, we’ve had chaos. Maybe it just took a few years before the effects of the preferential ballot were really felt. Or maybe it took this new voting system combined with a rapidly changing group of voters to upend how we understand the Best Picture race.

Why Nomadland Is Such a Heavy Favorite

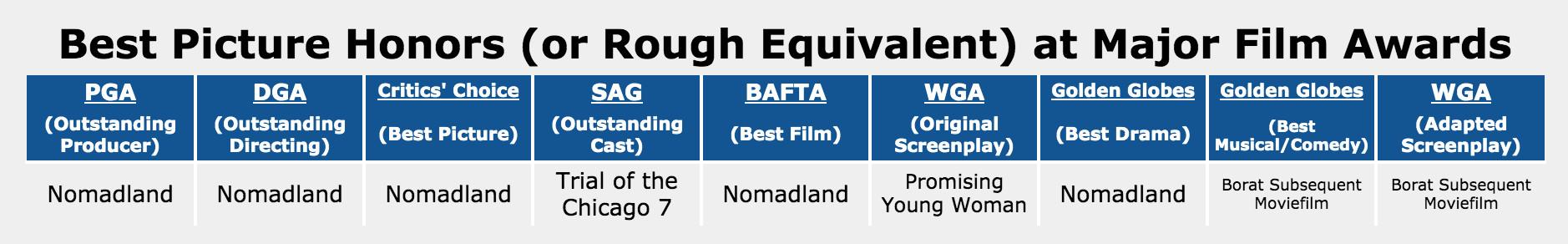

All right, so what does this all mean for this season’s awards? As mentioned above, Nomadland is the heaviest favorite in eight years. It’s a juggernaut. It won at almost every big precursor to the Oscars, including the PGAs, DGAs, and BAFTAs. Here’s how those “big” awards have shaken out this year:

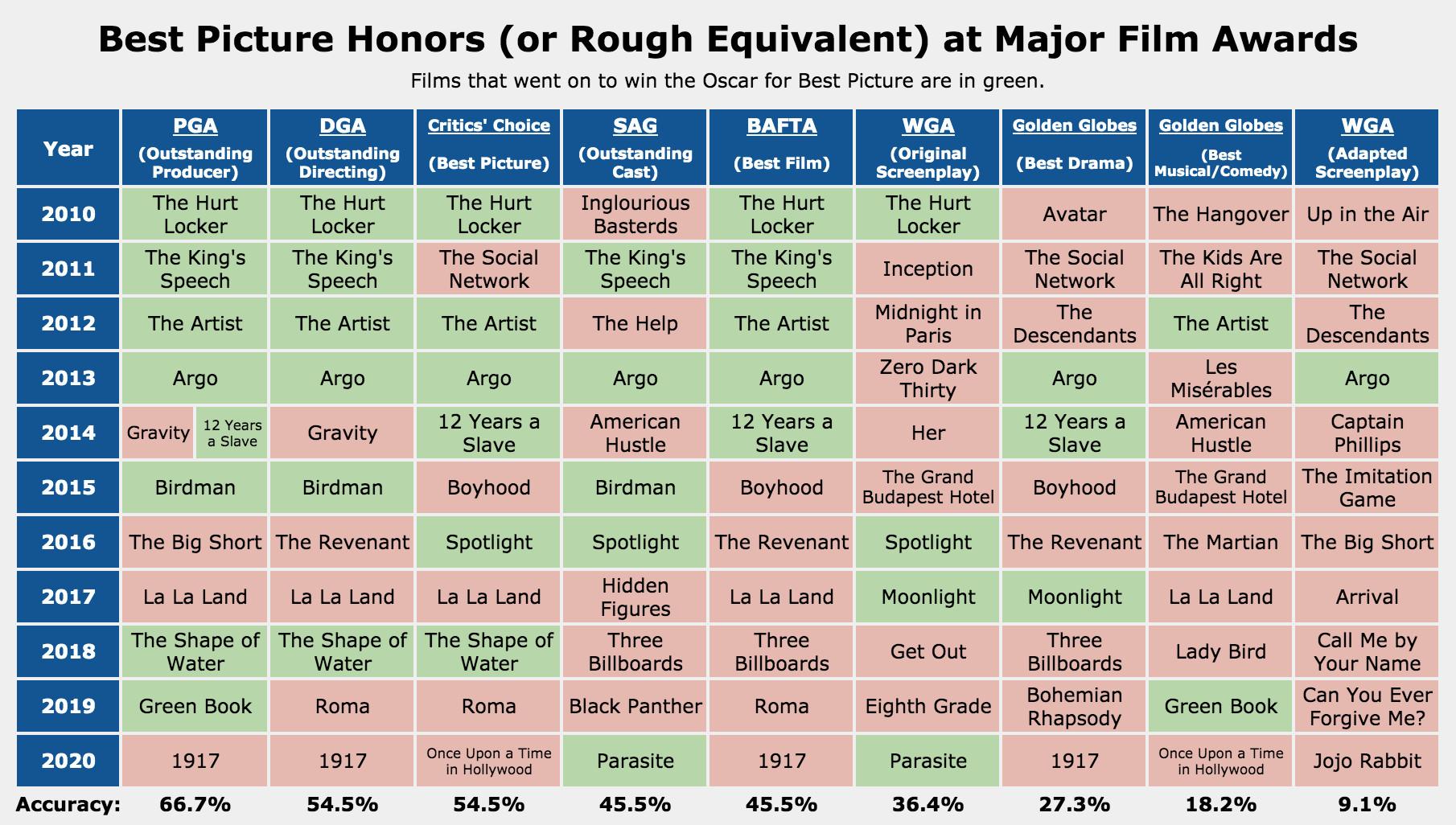

Of course, as I hinted at earlier, these awards haven’t been as predictive as they used to be. Here’s that same chart, but for the past 11 ceremonies (since the field of candidates was expanded), with the films that ultimately went on to win Best Picture highlighted in green:

The further down we look on this chart—that is to say, the more recent years that we look at—the more red we see. The big, centerpiece awards handed out at the PGAs, DGAs, and BAFTAs used to be dead ringers for the Best Picture Oscar. Film critics aren’t part of the Academy, but the Critics’ Choice award is also a nice feather for an aspiring film to have in its cap heading into awards night. The SAGs always have been hit-or-miss.

But those awards have less correlation with the Best Picture Oscar than ever. Last year the PGAs, DGAs, and BAFTAs all even agreed for only the second time since 2013, but just like with La La Land in 2017, the movie those three groups fell in love with, 1917, didn’t take home the main honor at the Academy Awards.

Still, Nomadland is strong. It has the same PGA, DGA, and BAFTA wins that 1917 had, plus a Critics’ Choice trophy to boot. And Chloé Zhao is as much a slam dunk for Best Director as we typically see. She won at the DGAs, the Golden Globes, the BAFTAs, and the Critics’ Choice Awards, among a laundry list of other accolades. While the Picture and Director awards have been more likely to split than ever (only three times in the past eight years have the two gone to the same film), Zhao’s clear runway to the Best Director trophy is an indication that moviegoers just love Nomadland.

Nomadland has six nominations in total, tied for second most for these awards. Notably, Frances McDormand is up for Best Actress, and the film is nominated for cinematography and editing awards. The film editing nomination can be crucial; 40 of the past 41 Best Picture winners have been nominated for that award—the lone exception being 2014’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance). 1917 didn’t have an editing nomination last year, a fact that proved prophetic.

Nomadland also won the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival when it premiered there in September. It then won the audience award at the Toronto International Film Festival. It’s been a Best Picture favorite ever since.

The Cracks in Nomadland’s Résumé

Nomadland has earned its juggernaut status, but if you’re looking for things to be concerned about when it comes to its Best Picture hopes, start with the acting. McDormand lost at the SAGs (to Viola Davis in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom), and Nomadland wasn’t nominated for Best Cast at those awards. McDormand may be up for Best Actress at the Academy Awards, but that’s Nomadland’s sole acting nomination.

There’s an easy explanation for this: Nomadland doesn’t have very many actors! Zhao opted to use real-life nomads playing fictional versions of themselves, so Nomadland was never going to come home with a haul of acting trophies. But still, if the Academy’s actors aren’t in love with Nomadland, that’s a concern. Actors may be declining in influence, but they are still the largest group of Oscars voters by a wide margin:

A lack of support from actors can be a harbinger of doom for a Best Picture favorite. Last year, 1917’s lack of any acting nominations—both at the Academy Awards and the SAGs—proved fatal for its Best Picture chances. None of Parasite’s actors were nominated at the Oscars, but the film won Best Cast at the SAGs, a clear sign that despite the lack of Academy Awards acting nominations, actors in Hollywood still respected the performances given in the film.

Beyond acting, it’s not clear how respected Nomadland is among writers. While it scored an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay, it was ineligible for a Writers Guild of America Award. The WGA has strict eligibility requirements (Mank, Minari, and The Father were also ineligible), and recent winners Birdman and 12 Years a Slave both won Best Picture and screenplay Oscars despite being no-shows at the WGAs. Many think Nomadland could do the same.

Beyond that, you really have to reach for flaws. Some critics have taken issue with the way Nomadland portrays Amazon and the gig economy. It’s not clear that the Academy will care. Zhao herself has addressed the criticism:

“If you look deeply, the issue of elder care as a casualty of capitalism is on every frame,” she told Vulture. “It’s just, yes, there’s the beautiful sunset behind it.”

The COVID-19 Shadow

You may have realized that the Oscars are usually in February, but it’s April right now. The pandemic prompted the Academy to extend award season, moving the ceremony back two months. It also extended the window for Oscars eligibility—this is essentially a 14-month year for movies, as far as the Oscars is concerned.

That’s led to some weird situations. For example, Judas and the Black Messiah and The Father were both widely released in February. In a normal year, that would mean they’d be in the running for the 2022 Oscars—not this weekend’s ceremony. In 2018, my colleague Zach Kram found that movies that were released late in the cycle—usually December—were winning less often than those released a few months earlier.

Most of the films that are up at this year’s Academy Awards are on streaming services, which is no doubt how many of the voters consumed them. Does the medium in which movies are viewed influence how they are perceived? Of course! If the 2021 Oscars produces another stunning moment, many will look at the pandemic to help explain why.

Which Film Would Be the Upset Pick?

Perhaps the biggest reason to believe Nomadland will win is this: There are no other strong contenders.

The Trial of the Chicago 7’s win for Best Cast at the SAGs has solidified it in second place. And while it has nominations for its writing, editing, and cinematography, Aaron Sorkin failed to secure a directing nomination. It also has a nomination for Supporting Actor (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Original Song. The SAG award proved to be a precursor for Parasite’s Oscar night, but Nomadland was never going to compete for that trophy, so it’s unclear how meaningful Trial’s SAG win will be. Every time these two films go head-to-head, Nomadland comes out on top.

Further down the list are true long shots. Promising Young Woman won at the WGAs and is the favorite for Original Screenplay, and also has nominations for Director, Actress, and Film Editing. But it hasn’t won any big awards anywhere, and it can be a polarizing film—the kind that may be uniquely hurt by the preferential ballot. Minari was once thought to be a front-runner but has failed to break out, though Youn Yuh-jung could be in line for a win in the Supporting Actress category. Mank has the most Oscar nominations (10) of any film, but doesn’t appear destined to win many trophies outside of Production Design, where it’s the favorite. The rest of the Best Picture nominees aren’t really worth a mention.

There just isn’t much competition. But then again, La La Land went into the 2017 ceremony seemingly without strong contenders either. At the modern Academy Awards, anything can happen.

Ultimately, Nomadland is the biggest favorite we’ve seen in some time, and it won’t be a shock if it wins on Sunday. But 2020 was a weird year. And at this point, nothing at the Oscars would be weirder than the favorite winning Best Picture.