The Sun Gods of the LBC

Twenty-five years ago, Sublime released their third album, a sprawling magnum opus of sunburned ska, punk, reggae, and stoner anthems that turned three kids from Southern California and a Dalmatian into legends. This is the story of how it came together, the tragic end of the band, and why the songs still live on.1. “It Smelled Like Lou Dog Inside the Van”

The first mistake was renting the RV. In Sublime’s defense, it seemed like an act of shrewd lunacy. A road trip allowed them to gig all along the 1,383-mile stretch from Long Beach to Austin. More importantly, it skirted any potential conflict between the “Smoke Two Joints” trio and the Federal Aviation Administration, an agency traditionally uncharitable to the interstate transport of illicit substances. Law enforcement in the Lone Star State was no more friendly, but it’s substantially easier to stash a week’s worth of narcotics in a 33-foot traveling motorcoach than the limited apertures of the human body.

At the end of the trail lay Willie Nelson’s Pedernales Studios, a hallowed shrine for habitually baked experimentation that had hosted Neil Young and Ray Charles, Carlos Santana and Daniel Johnston. No more harmonious spot could have existed for the LBC house-party heroes than the compound that the Red Headed Stranger terraformed into a 75-acre outlaw hacienda of breezy creativity and reefer madness. Its attitude was perhaps best defined by a hand-painted “No Shirt, No Shoes, No Problem” sign. Pure serendipity for a band whose lead singer, Bradley Nowell, could produce little photographic evidence of actually owning any shirts.

Jagged reefs lurked among the sun-surf-smoke-ska synthesists when they arrived on the shores of Lake Travis during the final weeks of the winter of 1996. In the wake of their unlikely, untasteful smash “Date Rape,” Sublime had signed to Gasoline Alley, a subsidiary of MCA, which warily financed the gonzo recording saga that would yield the six-times-platinum Sublime, released 25 years ago this week. Within months, Nowell would be dead of a heroin overdose, leaving behind an infant son, a widow, and a posthumous masterpiece that would become one of the most revered (and wrongly reviled) albums of the last quarter-century. On their first and only major-label album of originals, Sublime coughed up a bleached beachfront creole, a seedy pawn-shop slop of punk, reggae, and hip-hop. Widely imitated, it spawned three alternative-radio stoner anthems (“What I Got,” “Santeria,” and “Wrong Way”), and made the band the most inescapable fixtures on FM rock radio since Nirvana. But before that could happen, they had to make it up the driveway.

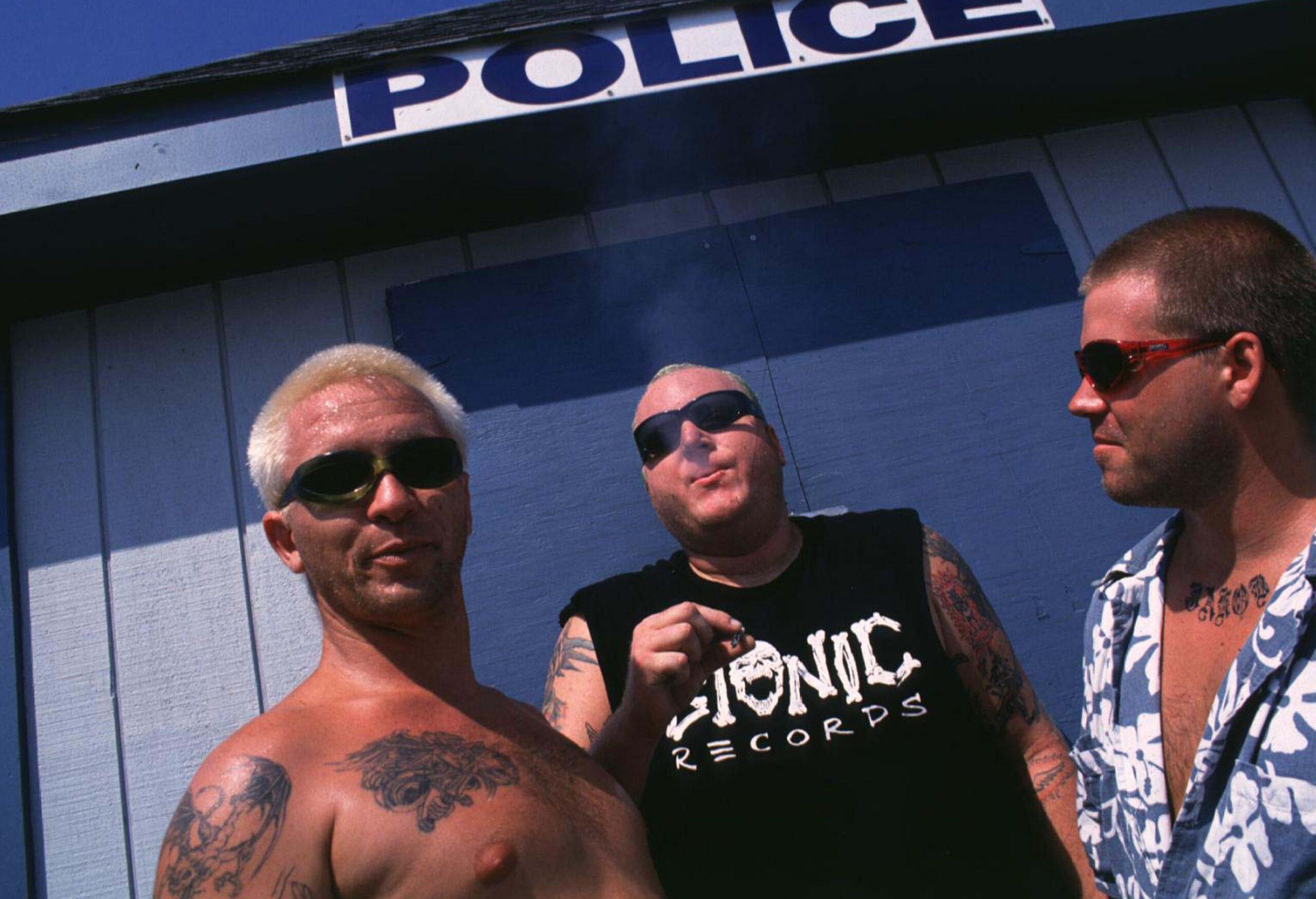

Maybe history should interpret it as a foul omen. After valiantly heaving through four states, the belching RV finally stalled out and collapsed on the steep incline that led to Nelson’s Xanadu. Picture the dysfunction: Nowell, bassist Eric Wilson, and drummer Bud Gaugh oozing out of the jalopy on that cold day in Texas. The studio employees were used to absolute freaks, but they still reeled from the tattooed pranksters’ Tasmanian chaos: pissing-in-the-sink drunk, squinting greasily into the daylight, reeking of stank dog, amphetamine gas, and stale Olde English. The canines weren’t invited either (error no. 2). That was one of the few rules of Pedernales, but Louie, the rescue Dalmatian, never left Nowell’s side. And if Louie came, that meant Wilson had to bring his basenji mix, Toby, too. No one remembers what happened to the RV.

Those were mere afterthoughts at the moment. After eight years of clobbering every house party from Belmont Shore to San Diego, every sweatbox club with skinhead audiences and strung-out promoters, they had finally “made it.” But Nowell was stressed: the pressures of delivering a hit compounded with the devils of addiction. MCA had already forked over six-figures-plus for his rehab stints. After swearing to his fiancée, Troy Dendekker, that he’d sober up for their newborn son, Brad relapsed again. He was about to turn 28, and plagued by a debilitating case of writer’s block.

“I was really concerned on the way to Texas because before, when we’d have studio time, we had everything down tight—so that it didn’t cost us an arm and a leg,” says drummer Bud Gaugh. “This time I turned to [Eric Wilson] and was like, ‘Dude, we got two, maybe three songs. What are we gonna do when we get out there?’ Eric said, ‘I don’t know, I guess we’re gonna have to figure it out.’”

Gaugh actually remembers the RV ride to Austin as a flight, which raises a consideration to take into account. (Leary distinctly recalls the broken-down bus.) If you can remember anything to do with Sublime with 100 percent accuracy, you probably weren’t there. This was the band that centered their 1992 debut album with “40oz. to Freedom,” and immediately followed it with a high hymnal that became generational wisdom: “I smoke two joints in the morning. I smoke two joints at night. I smoke two joints in the afternoon. It makes me feel all right.” They remain among humanity’s greatest endorsements for the willingness to risk long-term memory loss.

The Texas odyssey, detailed in an Austin Chronicle piece earlier this year, marked Sublime’s second attempt at recording the album. Round one partnered the band with David Kahne, a veteran producer for the Bangles and Fishbone. Most recently, Kahne had maestro’d MTV Unplugged for Tony Bennett, which netted them Album of the Year at the Grammys. But the similarities between that and the Sublime sessions started and ended with a Gershwin cover. The band’s late-’95 takeover of Redondo Beach’s Total Access Studios was so anarchic and druggy that Kahne reportedly called Sublime’s managers, Jon Phillips and Blaine Kaplan, at 6 a.m., freaking out and threatening to quit. For all the chaos, posterity was blessed with the rock radio eternals “What I Got,” “Caress Me Down,” “Doin’ Time,” and “April 29, 1992 (Miami).”

Inspired by mixtape culture, Nowell insisted that they needed a second producer to give the album a more eclectic sensibility. Kahne preferred drum samples and loops instead of the live rawness they sought. Enter Paul Leary, the guitarist for the scatological psych-carnival the Butthole Surfers, whose deranged subversion had been a formative influence. The admiration was mutual. Leary had recently become a Sublime convert, cranking up “Date Rape” every time he heard it on a Phoenix AM punk station during drives to sessions with the Meat Puppets, the alternative rock godheads he produced for at the time.

“When I was out in Tempe, they sent a demo tape [of the Kahne recordings], and it freaked me out,” Leary remembers. “I called them back and said, ‘Man, you guys should really just do whatever you’re doing on this. You don’t need me.’”

Sublime roundly disagreed. Sessions were scheduled at the Austin altar of Willie. But before the band headed to Texas, Leary went to Long Beach for preproduction. Dysfunction reigned. The plan was to spend a week in a practice studio, but Nowell vanished as soon as Leary arrived. Two days went by and still nothing. On night three, Leary reached the band and agreed to get breakfast with them the next morning. But the restaurant conveniently served giant tankers of beer.

“They all got drunk and decided to go surfing in Mexico, except for Brad, who probably felt sorry for me being out there with nothing to do,” Leary says. “So he took me over to his beautiful house on the beach with his beautiful wife and beautiful baby boy. He had a wonderful sense of really dry humor, and a look in his eyes like there was always something else on his mind—something troubling him.”

After hanging for a few hours, Nowell and Leary climbed up to the top deck of the lead singer’s new four-story house in Surfside, a gated beachfront community between Huntington Beach and Long Beach. They gazed at the postcard view, a short hike from one of Nowell’s favorite surfing meridians, as close to paradise as Leary could ever have pictured. Then Nowell asked the producer to loan him $10,000 to buy heroin.

“I was like, ‘I’m sorry, man, I don’t have 10,000 dollars,’” Leary says, laughing, the impact of time lightening the gravity. “He was like, ‘I’ll take a check!’”

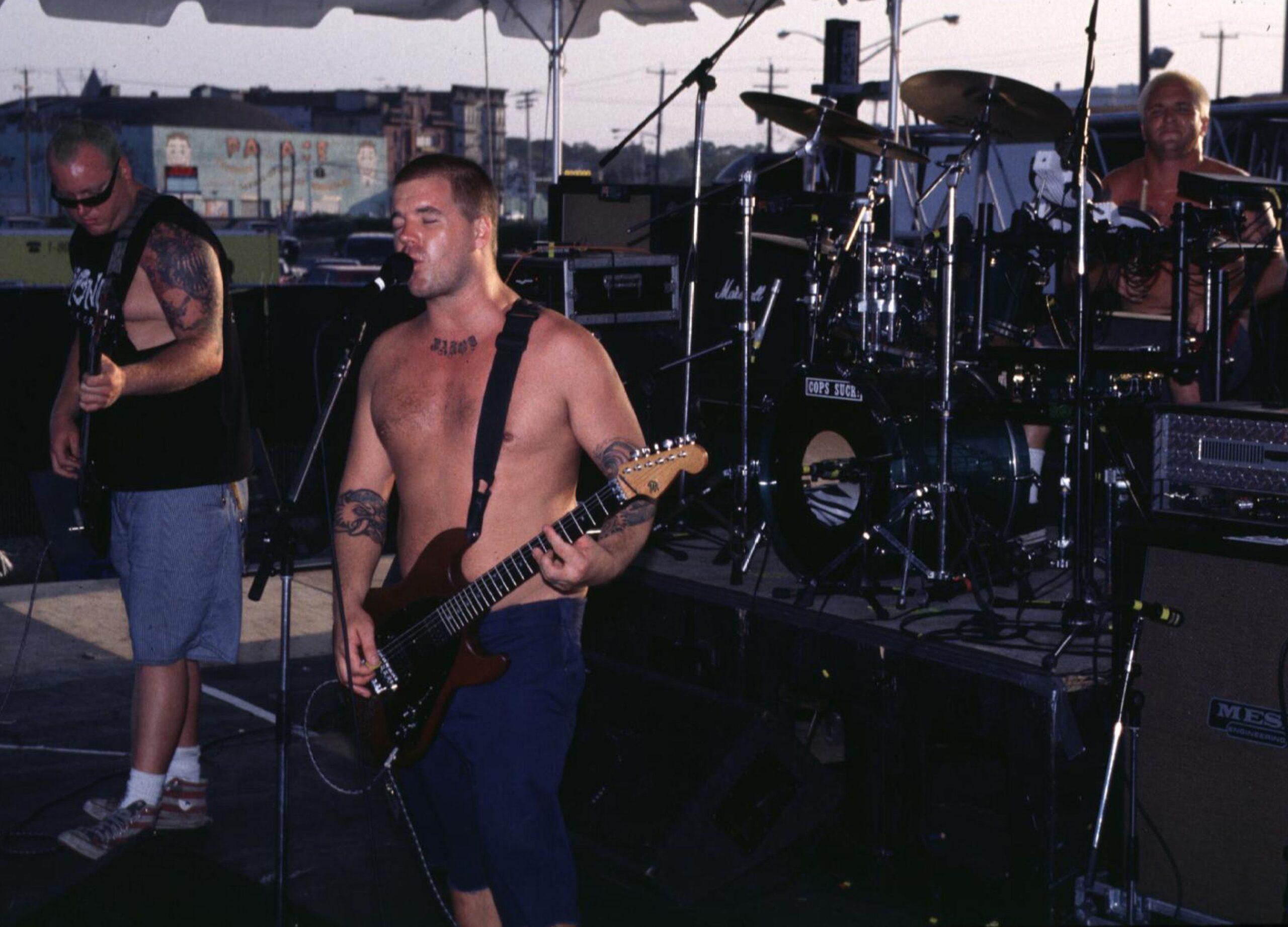

No notes were recorded during preproduction. But for all the extracurricular disarray, Sublime were consummate professionals in the recording booth. Most studio recordings are painstakingly composed of different layers of instrumentation from distinct takes. Most of the songs on Sublime were cut live on reel-to-reel. Sloppiness was an asset, an inspired rope-a-dope honed over a nearly nonstop decade of gigging. If the Beatles in Hamburg is the default cliché for the ideal 10,000 hours of cohesion, Sublime’s Star-Club was countless house parties in the backyards of Long Beach and all-night bonfires on the beaches of Ensenada.

“It’s amazing,” Leary adds. “They had obviously practiced that stuff an awful lot … and they were just that good.”

If Nowell’s best songs often revealed deceptively careful writing and wry storytelling, the drug binges didn’t lend themselves to narrative inspiration. In Pedernales, he kept insisting to Leary that he was going to spend time writing lyrics “for real,” but the producer figured that his improvised freestyles would be more effective. Quotables now long fabled in bong-rip lore often started as off-the-top gibberish. Leaving piles of tape on the floor, Leary and his engineer, Stuart Sullivan, took 10-minute Bradley rambles and ingeniously polished them into three-and-a-half-minute gems.

But the band’s exploits proved taxing. When they showed up Barney Gumble drunk to sessions that started at noon, Leary suggested an earlier time. The next morning, Sublime arrived armed with a pitcher of margaritas. A drug stash supposed to last the duration of recording barely made it a few days. Needing a re-up, Nowell sent a friend back to L.A. with an order so big that the dealer threw in a free 8-ball. (Wilson says that for the most part in Austin, he and Gaugh stuck to beer and weed.)

What else? Well, Lou Dog scratched up all the floors of the studio. When Sublime decided to hit the sauna, they draped a towel over a light bulb and set the chamber on fire. They borrowed a white Chevy Suburban that belonged to Pedernales and promptly crashed it. They wrecked the condominiums that had been provided to them, and had to be moved at least three times. On an afternoon spent golfing, Nowell and Gaugh flipped a golf cart and hit one of Nelson’s friend’s houses with a ball. For a finale, Leary walked into the studio one afternoon to discover that Sublime had drawn a Hitler mustache on Nelson’s face, defacing a poster depicting Shotgun Willie as Uncle Sam.

“I almost ended the session right there,” Leary says. “You just don’t do that to Willie’s studio.”

Sublime’s unofficial fourth member, their longtime producer, musical collaborator, and Skunk Records label co-owner, Michael “Miguel” Happoldt, graciously stepped in. Purchasing some colored pencils and whiteout, he spent an entire day miraculously restoring the handbill to where no remnants of der führer remained. (Happoldt swears to this day that it was actually a Charlie Chaplin toothbrush stache.)

After a break to play some SXSW shows, the tailspin accelerated. According to shaky modern-day memories, Gaugh and Wilson returned to Southern California, while Nowell, Happoldt, Leary, and Sublime’s other closest longtime collaborator, Marshall Goodman, all decamped to Arlyn Studios in downtown Austin for postproduction work. Better known as “Ras MG,” Goodman did overdubs, vocals, and turntable scratches on Sublime—and cowrote two songs.

“It was high tension, and that sometimes makes for good material, but for me experiencing that—Brad being my friend—it was a little rough,” Goodman says. “[The drugs] had definitely had a hold. It was normalcy.”

It didn’t help that Louie got kicked out of another hotel, and Nowell was forced to send him back to Southern California in a crate. Depressed, he spiraled down to Mexico for a bootleg valium spree. The Arlyn sessions weren’t without merit. Most notably, it’s here where Leary conceived the idea to add a Specials-inspired trombone riff in the middle of “Wrong Way.” But it’s also here where it became obvious that Nowell was unraveling. The hotel faxed the label gruesome details about the state of Nowell’s opiate den. The cleaning crew at Arlyn fretted over the needles they found. Leary feared that he’d find Nowell dead following one of his regular 45-minute trips to the bathroom.

“I was sending people back in to see if he was still alive. I was worried, and didn’t know what to do,” Leary says. “It eventually got so bad that I had to pull the plug; ‘I can’t watch you kill yourself like this anymore, you’re going home.’”

Enraged, Nowell fired Leary, his manager, and everyone else he had the capacity to dismiss. Later that evening, he calmed down and called up Leary to let him know that he understood and respected his decision. In the a.m., Leary drove out to the Sublime condo to see them off. Bradley had apparently agreed to check back into rehab. Their goodbyes were pleasant, but the producer was left with the grisly suspicion that he’d never see Bradley alive again.

2. “Well Qualified to Represent the LBC”

To understand Sublime is to understand the telepathy of Nowell, Gaugh, and Wilson, which is to understand the cultural dialect of Long Beach. And as Northside LBC historian Vince Staples once told me: to understand Long Beach is to recognize its diversity, as embodied by Sublime, Snoop Dogg, Nate Dogg, Warren G, and Cameron Diaz all simultaneously attending Long Beach public high schools in the late ’80s. As the story goes, the future all-American Mary bought weed from a pre-Chronic Snoop at Long Beach Poly. A few miles down East Anaheim Street, past the Eastside and Cambodia Town, Nowell attended Wilson High, bashing out malt liquor punk in Sublime’s first iterations, Hogan’s Heroes and Sloppy Seconds.

It’s slightly inaccurate to say that Long Beach is the shadow twin of L.A., the shiny mythologized beast sprawling on the other side of the 405. The two cities are naturally intertwined: same county, same radio stations, same smog. Different sets, but the same gangs. The differences are subtle to outsiders but significant to anyone attuned to the socioeconomic and tattoo differences among the 310, the 562, and the 714 area codes (let alone when the 213 split off around the time that Sublime dropped 40oz. to Freedom).

Pockets of wealth exist in Long Beach, but it’s historically a blue-collar port city, a hub of petrochemical behemoths and, at one time, aerospace titans, receptive to immigrants from Southeast Asia and Latin America. It is to L.A. what Oakland is to San Francisco, Tacoma is to Seattle, and Baltimore is to Washington, D.C.—unvarnished and raw, stripped of artifice and delusion, the ideal particle collider to spin out radical styles, weird scenes, and original ideas. It’s where Sublime created their own form of Southern California fusion with a lead singer who could croon alcoholic symphonies punctuated by lewd Eazy-E come-ons, then switch to serenades in fluent Spanish, right down to the slang, stripped of all traces of gringo accent. An iconoclast who gracefully avoided the “Ras Trent” trappings of white boy reggae, and competently reinvented a Grateful Dead classic. He could write pop hits off a Gershwin flip and then have them remixed by Snoop and the Pharcyde. That was Sublime, that was Long Beach.

It could’ve gone terribly wrong. Nothing against Orange County (maybe a little), where Nowell spent most of his early years, but had he stayed there, his talent would’ve been partially squandered. In the homogenous capital of Reagan Land, the future author of “Freeway Time in LA County Jail” might have bombed Jäeger alongside the USC-bound Young Republicans of the post–John Birch dominion: the scions of savings-and-loan shysters, slippery defense contractors, investment fraud golems, and plasticine real estate brokers. Imagine if mayonnaise could surf. Instead, Sublime’s first semi-official recordings featured “Live at E’s,” a song with a title inspired by Nowell’s excitement to record at Cal State Dominguez Hills’ studios, just a short blunt cruise from the ancestral Eastside Compton home of Eazy-E. One of Nowell’s earliest bands, Sloppy Seconds, featured Ras MG’s sister, Ruth, a saxophonist who Snoop (then Calvin) had once tried to date. Bradley was raised hood-adjacent; in the O.C., he might as well have looked at hip-hop and reggae through a telescope.

“Long Beach was a really musical city,” Gaugh says while discussing the time and place that produced one of Sublime’s most overlooked predecessors, the lowriding ’70s fusionists War. “Driving down the street with your windows down, you’d hear five different types of music down five different blocks. Latin jazz, hip-hop, rock … Cal Tjader on one corner, P-Funk on the next.”

Nowell’s parents were high school sweethearts from the Sunland-Tujunga area of the East San Fernando Valley. His father, Jim, was a successful general contractor; his mother, Nancy, taught piano and flute, and sang with perfect pitch. It was a musical lineage. At family parties, the Nowells and their kin brought out guitars, banjos, and harmonicas for impromptu jam sessions, sing-alongs, and dances. The kids took turns selecting the next standards from Jim’s songbook. In the house, folk music and country reigned: John Denver, Glen Campbell, the Carpenters, Linda Ronstadt. A lot of Patsy Cline, Waylon Jennings, and Hank Williams, too, especially after Jim went through his urban cowboy phase shortly after the divorce. Until then, Bradley’s childhood had been relatively idyllic. Born in Long Beach, most of his first 10 years were spent on a Tustin Hills plot of land that led out into the old Irvine Ranch. These were the last days of agrarian Orange County, where his backyard abutted asparagus fields and orange groves. After his parents split, the quiet and shy book obsessive, who loved surfing and sailing, became increasingly rowdy. Report cards branded him “hyperactive” and “disruptive.” A psychiatrist dispensed a Ritalin prescription in an attempt to restrain him.

“At the time, it seemed like a good thing,” remembers his sister Kellie Nowell, who helms the Nowell Family Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to helping people in the music industry struggling with substance misuse. “Ritalin made him much calmer, but he hated the way that it made him feel. Obviously, they’ve changed a lot about how it works now, but there were back-and-forth swings then. He was either completely out of control or sedated.”

At 14, Bradley’s mother sent the sensitive and emotional teenager to Long Beach to live with his father, a barrel-chested, business-minded beach devotee with a closet full of Hawaiian shirts. By then, Bradley’s plan of action had been plotted. In the wake of the marital dissolution, Jim and Bradley took a father-and-son trip to the Virgin Islands, which exposed the younger Nowell to the Caribbean sounds that captured his imagination. Shortly thereafter, he met Eric Wilson at tryouts for a junior high band. Nowell didn’t make the cut, but he and Wilson eventually formed Hogan’s Heroes, which nodded at their anarchic punk roots by swiping their name from a ’60s CBS sitcom about a German POW camp.

Wilson hailed from a multigenerational clan of musicians. His father, Billy, a big band jazz drummer, had one of those vagabond 20th-century adventurer careers that might as well have come straight out of a Jack London novel. Billy Wilson honed his chops in his father’s band in Depression-era Oakland, then gigged on cruise ships and in the Shanghai Philharmonic in pre-revolutionary China. After a World War II stint in the United States Coast Guard band, and another putting calfskin heads on drums in Burbank music shops, the elder Wilson wound up at the Ostrich Club on the L.A. Harbor Naval Base, met Eric’s mom, and bought a home in a trailer park. His career ended in the Long Beach Municipal Band, which offered a decent pension and the time to teach everything he knew to his trumpet-player-turned-bassist son and his best friend, Bud Gaugh.

Apart from the usual candidates (Bad Brains, the Minutemen, the Wailers, the Clash, the Dead Kennedys, Millions of Dead Cops, dozens of other canonized and forgotten punk, reggae, and classic rock bands), Bill Wilson was the most formative early influence on what eventually became Sublime.

“Bill Wilson was like a second father to me, a total inspiration,” Bud Gaugh says. “He was like, ‘I used music so I didn’t have to carry a rifle. I did my tour of duty playing USO shows. I’m hanging out with all the girls and Bob Hope and doing all these fun shows and entertaining the soldiers so I didn’t have to carry a rifle. Music will be good to you if you’re good to it.’ Then I was like, ‘Well, that was a different time. You were playing popular music.’ And he’s like, ‘Hey, man, my parents hated jazz music. They were classical, and I was playing the punk rock of the time.’ And I was like, ‘Hmm, wow, OK. Let’s give this jazz thing a try.’”

The vision materialized in 1982 when Gaugh’s father, a drill press operator turned Southern California Edison employee, took his son and Wilson to see the Clash and the Who at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Even with Keith Moon cremated, the Who opened Gaugh to rock’s possibilities. “I think that’s about it,” Wilson remembers from his ranch in rural Northern San Diego County, nearly four full decades later. “I pretty much wanted to figure out the guitar or the bass.”

His obsession with Jimi Hendrix, Ginger Baker, and John Bonham deepened. Rock stardom beckoned, but the gap between reality and expectation remained distant. Wilson started ditching class and doing drugs and ended up in continuation school. Gaugh was slightly more academically oriented, but skipped higher education. Nowell was the exception. Even though he was already snorting coke, smoking weed, and drinking heavily by his mid-teens, an innate scholasticism earned him admission to UC Santa Cruz. A photo excavated for the 2019 documentary Sublime perfectly captures Nowell at 18. He’s Dennis the Menace playing Spicoli, half-angelic, baby-faced, slightly pudgy, and exorbitantly stoned, with a glint of mischief subverting his dimpled grin. His dorm room walls are decorated with Surf magazine cutouts and handbills of Burning Spear and Bunny Wailer concerts. Unlike the historical majority of white Santa Cruz reggae bros, Bradley does not sport dreads.

Sublime officially began on Ocean Boulevard, a fact so absurd that it had to be true. During the spring break of his sophomore year, Bradley returned home to Jim’s house in Long Beach’s upscale Peninsula neighborhood, a mile-long spit surrounded on both sides by beaches. Gaugh had just been bailed out of jail for some minor indiscretion and was back home playing in punk bands alongside Wilson. Figuring the trio needed to jam, Wilson brought the drummer over to Bradley’s garage one afternoon; a week later they emerged with three new songs (“Romeo,” “Roots of Creation,” and “New Realization”) and two recordings of Nowell originals (“Date Rape” and “Ebin”).

“I was like, ‘Huh, surfer kid. Seems pretty clean-cut—is he gonna be able to keep up with us?’” Gaugh recalls of his first impression of Nowell. “Then he started playing guitar and I was like, ‘What the fuck is this shit?’ This little fuckin’ ska song. I was like, ‘Eh, do something a little harder.’ Then he started singing and I was like, ‘Holy shit, this kid’s got some pipes!’ So we started talking about different punk rock influences, and he was like, ‘Hey, let’s play a Defenders song.’ It was like, ‘Right on, he’s got grit, fuck yeah.’”

In the grand tradition of bands picking their name by randomly looking up words in the dictionary, they settled on Sublime. After school got out two months later, Nowell transferred to Cal State Long Beach to be closer to his bandmates.

“We just wanted to be Bad Brains, that’s all,” Wilson says. “From the first songs we wrote as Sublime, I knew that we were gonna do it. I didn’t worry about how we were gonna get there, I just kept playing.”

For the next two years, Nowell studied business and even made the dean’s list in 1990. But he eventually dropped out a semester short of graduation. Sublime had become a monomaniacal obsession. Those first few years of the band are easily mythologized, and for good reason. The drugs hadn’t yet taken hold and there were no industry machinations to navigate. It was simply the music: all-night house parties in Long Beach, and now hazily remembered performances at Bogart’s, the city’s biggest underground club. To start booking shows, they recorded a sneakily fully formed five-song demo, which became known as the Zepeda Tape. Its handmade cover listed the song titles and a means to contact them: “For Booking Call (213) 438-4836—Brad,” it read. But they were still too young to get into the bars, so you could catch them jamming in the canals in Naples, out on Second Street, rolling up joints with the acoustic guitar box open, jamming out, getting booked by bystanders to play backyard parties for free beer.

The parties. This is the first thing that anyone long associated with Sublime remembers about the band’s early years, when they became the official Long Beach house band, inheriting the throne vacated by T.S.O.L. and local legends the Falling Idols. Sublime was suddenly everywhere: backing H.R. from Bad Brains before an audience of Cal State Long Beach students at the Nugget, freestyling with Ras MG at debaucheries on the Westside, and rocking proto-Project X ragers with kids skating on half-pipes on the Eastside. They even set it off in northside Long Beach, not far from Ramona Park. For a while, the Sons of Samoa, a Long Beach Samoan Crip gang, acted as their bodyguards.

“We would play at some of these parties in North Long Beach and people were like, ‘Yeah, we dig that fuckin’ reggae sound,’” Gaugh remembers. “Then we’d play over on the Westside, and it would get crazy sometimes. One time they wanted to keep our equipment. It was like, ‘Woah woah woah! No!’”

This was the LBC in the late ’80s and early ’90s. The crack epidemic was in full swing, which brought with it territorial issues and repression by the police. Surfing and skating were big, blending into nearly every neighborhood. So did punk rock and the reggae scene. And Sublime remained just a single degree of separation from Warren G, Snoop, and Nate Dogg, then rapping as 213. Different cultural pockets scattered across the city, but Sublime’s syncretistic approach distilled that international Babel into one accessible translation.

At one of those ’89 keggers, Sublime crossed paths with Michael “Miguel” Happoldt, a recording student and member of the “cowpunksurfabilly” band the Ziggens. Needing to record a band for a school project, the budding producer asked Nowell whether he was interested in laying down tracks in a professional studio. In its first recorded version, the future Sublime standard “Badfish” earned Happoldt a C-minus. (The teacher said the “bass was not even close to being balanced.”)

Pedantic miscalculations aside, the chemistry between Happoldt and the band was self-evident. He became their first producer and occasional backup guitarist and harmony singer—recording their unofficial debut, 1991’s Jah Won’t Pay the Bills, in the middle of the night at the Cal State Dominguez studios. Released on Happoldt and Nowell’s fledgling Skunk Records imprint, it didn’t sell much, but became a calling card that helped them secure gigs up and down the coast.

“When I met Brad, he just wanted to make great records,” Happoldt remembers. “People will say they were either very good or very bad. … [But] when I first met them I never saw a bad show. Even smashed out of their minds they were still fantastic.”

Around this time, Gaugh had developed a heroin and speed problem, and would largely disappear into seclusion in Anaheim for the next two years, leaving Ras MG (and later Kelly Vargas) to handle percussion. It’s Ras MG playing the drums on the near entirety of their first classic, 40oz. to Freedom, which dropped on Skunk in December ’91. His influence throughout their catalog—but especially on that album—indicts the lazy stereotype that Sublime were alabaster culture vultures. Steeped in hip-hop culture, Ras MG, who is Black, met Nowell when they were both teenagers. From the next room at band practice, Nowell heard him scratching records from the seminal electro-rap pioneers the L.A. Dream Team.

“I was doing some DJ stuff called back-spinning,” Ras MG recalls. “He didn’t understand how I was doing that. … He was just intrigued by all that, and he was trying to do it and everything.”

Hip-hop formed another pillar of the band’s sound. Nowell and Goodman bonded over the first Brand Nubian record and Gang Starr. Wilson and Gaugh cite the crew’s mutual love of the Geto Boys, N.W.A, and Public Enemy, and later on Cypress Hill, Dre, and Snoop. But for Nowell, the two most consequential were KRS-One and the Beastie Boys. No trace of irony existed on the 40oz. to Freedom tribute to the Boogie Down “edutainer.” For a perpetual seeker like Nowell, the young KRS offered knowledge of self; in his gift for flipping classic reggae and dancehall toasting into hip-hop, Nowell saw a platonic ideal. Paul’s Boutique had a similar effect. Here was a trio of smart-ass ex-punks who not only could rap, but discovered how to weave a goofy psychedelic bricolage of all the greatest music ever recorded into their sound. 40oz. to Freedom might as well be a response record.

You can play the spot the influence all day: The English Beat, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, Fishbone, Big Audio Dynamite, the Police, the Specials, too many reggae immortals to list. Nowell religiously listened to DJ Roberto Angotti, an extraordinary digger who initially appeared on Long Beach’s KNAC before graduating to host KROQ’s Reggae Revolution (Happoldt made a whole playlist of their favorites from the computerized dancehall era). Long before Blood Sugar Sex Magik, the Red Hot Chili Peppers were already L.A.’s berserk prodigal sons, and the George Clinton–produced Freaky Styley rarely left Sublime’s stereos for very long. Across the city, Rage Against the Machine incorporated metal into hip-hop and hardcore similarly to how Sublime blended reggae. More than anything, Nowell became obsessed with individual songs, a harbinger of the shuffle culture that followed decades after his death. He might not have been a Deadhead, but he loved “Scarlet Begonias,” and had an intimate familiarity with Shakedown Street.

“Brad was never all in on anything,” Happoldt says, laughing. “He was the cherry-picker guy. You’d ask him if he liked an artist, and he’d just be like, ‘I like that one tune.’ He reserved his judgment. … He collected those little nuggets. He was like, ‘That’s what the future is!’”

The present was depressingly bleak. They might have been regional beach gods, able to sell out small clubs from Escondido to Arcata, but by the end of ’92, their prospects appeared limited. No major label wanted to sign the band. They briefly inked a pact with True Sound, the Island-affiliated imprint of Heptones producer Danny Holloway. But things declined quickly after a strung-out, baseball-bat-wielding Nowell tried to rob his label boss for drug money. Epitaph expressed interest too, but passed when Nowell drank 40s and smoked crack in the studio, an untenable act for the label’s newly sober founder, Bad Religion guitarist Brett Gurewitz. According to Happoldt, they once gave a CD to Rick Rubin. As he drove off, he flung it out the window of his limo onto Sunset Boulevard, cracking it into pieces.

After a strong start, sales of 40oz. to Freedom started dwindling. Addiction took over. Nowell was smoking anything he could get his hands on and fully bought into the rock star heroin myth, believing that opiates spurred the creative process. Before shows, he’d hock the band’s instruments at pawn shops, knowing someone would have to buy them back in order for them to play that night. Exhausting the patience of friends and family, Nowell hit what was then rock bottom. High off everything, he moved his meager belongings and Louie into a tweaker pad in San Clemente (the S.T.P.), where he wrote and recorded part of the group’s weakest project, 1994’s Robbin’ the Hood. Made on equipment heisted during the ’92 riots, it actually functions impressively as a post-Steinski precursor to lo-fi beat tapes (with a Gwen Stefani feature), but as a polished statement of purpose he sounds too fucked up to even properly record a cry for help.

It could’ve been curtains. Kurt Cobain was a few months away from death, and Nowell seemed a likely candidate to follow him. Except for the Sublime frontman there would have been no MTV requiems or Rolling Stone covers—at least until “Date Rape” randomly became the biggest song on KROQ in August ’94, three years after it was first released. It’s one of those FM fables that could never happen again. A local DJ named Tazy Phyllipz plucked a live rendition of “Date Rape” from an obscure band compilation discovered at the massively influential station’s Burbank studios. One play was all it took. The phone request lines lit up. It was the ’90s.

Off the strength of a crass novelty hit that they’d already taken out of their set list, Sublime became the hottest unsigned commodity on the West Coast. Eventually, they signed to Gasoline Alley, an MCA subsidiary owned by Randy Phillips, the manager of Rod Stewart. He’d been sold by his nephew Jon, one of the label’s A&Rs, who eventually started managing the band. Of course, the trio nearly managed to torpedo the deal when right after a negotiations meeting, they slapped a Sublime bumper sticker on the elder Phillips’s brand-new BMW.

“Fuckin BMW, big deal,” Gaugh says, prankishly smirking through the phone. “If it was a fuckin 300SL Gullwing, then I can understand.”

Rather than send the band into the studio to record their next LP, Gasoline Alley insisted that Sublime barnstorm the re-released 40oz. to Freedom now that the major-label marketing machine was turning “Date Rape” into a nationwide hit. In the summer of ’95, they co-headlined the first Vans Warped tour, which legendarily devolved into scenes of Lou Dog attacking the skateboarders and a very drunk Sublime starting a mud fight with an upstate New York crowd. As punishment, the tour’s founder kicked them off for a week. When Sublime played that rock radio rite of passage the KROQ Weenie Roast they felt like they weren’t given enough backstage passes. So they counterfeited enough to invite half of Long Beach. By nightfall, Lou Dog had sunk his teeth into the daughter of a record executive, one of their friends had nearly puked on MTV’s Kennedy, and they’d stolen all the beer and liquor from Bush’s trailer while the runway grungers were onstage. When they returned, “Shrub” was tagged everywhere.

The road brought all the predictable temptations. The band descended into a Groundhog’s Day routine: waking up in an unfamiliar city, drinking all day, playing a show at night, and drinking again until they passed out. In an attempt to protect their investment and ideally save his life, Gasoline Alley raided the MCA treasury to pay for Nowell’s rehab. Finally, a late-’95 stay seemed to have had a positive impact. The birth of his son compelled him to get sober, or at least close enough—then they rented the RV and drove to Texas.

3. “Are You Gonna Call 9-1-1 and Spoil All of My Fun?”

True chaos requires the illusion of stability. People latched onto his periods of sobriety and focus. Each time, his intelligence and charisma convinced even the most recalcitrant skeptics that he’d kicked the habit for good. Some people are experts at hiding their addiction. He was the opposite, transparent to a fault. When he returned home from Texas, he writhed with sickness for three days. Distraught at his condition and seeking a safer environment, his soon-to-be-wife, Troy, took their infant son, Jakob, to her mother’s house. When his dad showed up to confront him, Bradley profusely apologized for being such a disappointment. Father and son hugged in their kitchen.

“I couldn’t be prouder of your music and all the things that you’ve done, but at the same time I’m definitely afraid you’re going to kill yourself,” Jim Nowell reportedly said at that intervention.

The details are murky about the ensuing rehab stint, but those closest to Bradley reported that upon his remergence, it was the most joyous that he’d ever been. Troy remembers him loudly bumping early versions of the record in his Ford Bronco.

“I’d be driving and he’d be messing with all the knobs, trying to get the equalizer just right,” she says. “There were some songs he hadn’t even heard the final versions of—and he was so happy and proud of what they’d accomplished.”

To symbolize this fresh start, he proposed to Troy. On May 18, the couple were married in a Hawaiian-themed ceremony in Las Vegas. Afterward, the newlyweds and their friends gambled and boozed late into the night. The photos from the evening reveal a rare non-opiated euphoria in Nowell’s eyes. His face was fleshier, too, indicative that he’d begun to put weight back on after the drug bender. A few days later, Sublime began a short West Coast swing from which he’d never return.

The first show was at a Gen X orgy called Cheekopalooka. Held at a park in Chico, hordes of heavily tattooed and pierced crustpunks gathered to watch an opening act swallow swords and insert nails through his nose. At one point, dozens banded together to help search for a severed finger. Sublime’s booking agent described it as “one of the most insane, crazy rock ’n’ roll shows I’ve ever seen in my life. There were probably 2,000 people there. The fence got torn down, security was overwhelmed.”

At the afterparty, Nowell reportedly demanded the bodyguard hired to save him from himself give him money to buy drugs. The sentry refused, but illicit fuel wasn’t tough to find. The band crashed at a college girl’s house and smoked crack for breakfast. No one knows exactly how Nowell scored the fatal bag of heroin, but it was in his possession the next night, after their final show in Petaluma. By most accounts, the show was uneven and sloppy, but according to Troy, he called her afterward in ecstasy.

“He wanted to tell me how much he loved Jakob and me, and that they had the best show ever that night. It was the happiest I had ever heard him,” Dendekker said on the Sublime episode of Behind the Music. “I could tell that he’d been partying, you know, and I was a little concerned. But I didn’t want to argue with him, because he was so happy.”

Rather than spend the night in Sonoma County, the band tilted their 27-foot 1967 school bus to San Francisco, where Sublime had booked a room at the Ocean View Motel in the Outer Sunset district. You know the type: a crummy flophouse with soiled tourist brochures for Ripley’s Believe It or Not! and Alcatraz in the lobby. Located at the edge of the earth, a quiet, terminally gray surfer enclave, right where Golden Gate Park sighs into the sea.

They arrived in the Sunset late, but Brad wanted to keep partying. Around 2 a.m., he tried to convince Bud to go outside with him. Bud declined. Instead, the drummer sneaked into Bradley’s stash, shot up, and passed out. Bradley futilely attempted to wake up Happoldt and Wilson, then he grabbed Louie and haunted the sands of Ocean Beach until sunrise, awed by the treacherous 10-foot waves. As the ashen dawn broke, the man who finally had it all crawled into bed with his Dalmatian. One bad shot poisoned everything.

Gaugh awoke the next morning to discover Bradley sprawled akimbo, naked. Curled at the edge of the mattress, Lou Dog whimpered mournfully. A crust of yellow and white mucus coated Nowell’s mouth. There was no doubt of an overdose.

“I thought I was in hell,” Gaugh told the Los Angeles Times several months later. “I thought, ‘That was probably supposed to be me.’ The Grim Reaper saw him laying on his side, saw the tattoos and thought, ‘That must be Bud.’”

Gaugh frenziedly tried to resuscitate his best friend, but he was already long gone. In the bus outside, a hungover Wilson sent a friend inside the hotel to fetch ice for Bloody Marys. He returned in tears, fitfully breaking the news. The paramedics arrived and rushed Nowell to the hospital. No chance. The coroner pronounced him dead at 11:30 a.m., May 25, 1996. Seven days after the wedding. Twenty-eight years old.

Back in Long Beach, there was shock and emotional devastation, but little surprise. In the national media, Nowell’s death barely registered a blip. The July overdose death of the Smashing Pumpkins’ touring keyboardist, Jonathan Melvoin, received far more attention. As for the band, they were obviously finished. Without their frontman, chief songwriter, and creative mastermind, there was no point. Sublime weren’t even Sublime yet. From the outside, it appeared that their former tourmates and collaborators No Doubt had lapped them and were on the verge of breaking out Tragic Kingdom. Had Sublime never been released, it’s possible that they would’ve been remembered as one-hit wonders from the ska boom. Much more gifted, sure, but no more notable than Reel Big Fish, from neighboring Los Alamitos.

MCA nearly made them a half-forgotten, mid-’90s curio, initially shelving the eventual sextuple-platinum classic. Having already hemorrhaged an estimated half a million dollars in tour support, rehab bills, advances, and recording costs, they figured that the wise move was to cut their losses. Without Nowell around to promote and tour Sublime, Gasoline Alley figured that it would be a bomb. Might as well avoid the promotion and manufacturing fees.

“[We were thinking] how can you be so ignorant?” Gaugh says about first hearing the news that Sublime would never see the light of day. “It was like, ‘Holy shit, dude, this [album] is such a fuckin’ sleeper. We just got fuckin benched?”

As with all stories intertwined with money, drugs, and tragedy, there are different accounts of what led the Gasoline Alley executives to reconsider their decision.

“The label was dissolving, and we owed so much money,” Happoldt says. “They didn’t hear the hit. ... They listened to the self-titled and were like, ‘Hmm, how much is this gonna cost us?’ This wasn’t Berry Gordy we were dealing with.”

It was still the era where burning CDs was prohibitively expensive. According to Happoldt, less than five copies existed of the unreleased record, one of which he slipped to KROQ’s Jed the Fish. Within a matter of weeks, “What I Got” became the most popular song on the station. A hit is a hit. Production ramped up. Sublime dropped on July 30, 1996, barely two months after Bradley took his final bow. A quarter-century later, there’s still a good chance that you will hear it blasting at any given red light, at least if the weather is warm.

4. “We Gonna Rule This Land Among Children”

If you’re of a certain age and geographic profile, the lyrics from Sublime are as ingrained into your memory as the name scripted in Olde English on the cover. For a period in the late ’90s and early ’00s, you would have thought that weed dealers were giving it away free with the purchase of every eighth. But for all the stoner bro association, the band transcended their core fan base. Nowell’s simplicity as a writer disguised his skill in storytelling. From the first bars, they’re off to Garden Grove, with the foul scent of unbathed Dalmatian in the Econoline and a .22 pistol in the trunk. He slyly name-checks a Bob Marley classic, but this ain’t that. $5 at the door. It’s L.A. punk noir, but goofy and moody. The Dude in the Minutemen.

You learn the Tao of Bradley in those first few minutes of “Garden Grove.” He’s a lovesick fool, but he’ll fuck you up if you mess with his dog. An artful thief in the night pillaging and reimagining sounds, but half-crazy. He tells the driver of the van to pull over. His soul’s unsound. They nick a bass line from Courtney Melody’s “Ninja Mi Ninja” and sample Linton Kwesi Johnson’s “Five Nights of Bleeding.” Then Nowell unleashes a litany of complaints that might as well have inspired Atmosphere’s “Scapegoat.” All the aggravation that leads to his despair. A bad-moon funk of shitty opening bands and dog shit under his shoe, sandy bedsheets and the torments of addiction. It is infrared targeted to appeal to broke, depressive teenagers and post-adolescents. Pure ’90s slacker malaise and the permanent guilt of not meeting parental expectations.

Kurt Cobain opted for visionary poetic symbolism to veil his existential grief while Nowell was hitting the main vein on a street corner; teenage angst hadn’t paid off yet. In the same way that Cobain introduced the pre-internet mainstream to underground kings like the Vaselines, the Melvins, and the Pixies, Nowell introduced his audience—whose understanding of reggae barely exceeded Legend—to Half Pint, Clement Irie, and Yellowman.

Sublime is one of those albums so bludgeoned by terrestrial radio and tattoo parlor ambience that it’s difficult to separate from its context. There is a solid chance that it reminds you of the worst people that you have ever encountered: natty dread white boys saying the N-word in freestyles, but telling you about the righteousness of Jah; aggro ex-jocks with barbed wire inked on their biceps; mask skeptics with Oakleys and F-150s who bemoan wokeneness and wonder why “no one writes funny songs like ‘Date Rape’ anymore”; anyone who has ever attended a Kottonmouth Kings concert. You can hate the fans, but you can’t blame Sublime. They artfully captured the dirtbag lifestyle, the scuzzy surf and skate culture that once characterized the Southern California littoral. Genius disguised as a joker, a Trojan horse that offered a gateway into lost cult punk classics and Jamaican genius. They could be crude and profane, but Nowell was about as subtle as you can get for being profoundly unsubtle.

The dysmorphia of time would lead you to believe that Sublime was a smash as soon as it hit Sam Goodys across the U.S., but it didn’t reach the top 20 of the Billboard 200 until May of ’97. It was propelled by the ubiquity of “What I Got,” which topped the Modern Rock Tracks chart. The song rivals probably only “Smells Like Teen Spirit” as the anthem most bled to death from the period. But if you approach it without the sensory memories of bong water spills, it remains a startlingly transfixing opus of pop songcraft, musicality, and cunning, specific lyricism. It starts with the drums, courtesy of Ras MG, that started as a loop played into a 4-track recorder from a little rickety drum set. Gaugh laid down alternate versions, but this one supplies a muscular hip-hop propulsion. Nowell has the gift of immediately painting the scene: “Early in the morning, risin’ to the street / Light me up that cigarette and I’ll strap shoes on my feet.”

The rest is memorized, but in retrospect it’s still dazzlingly weird. He’s broke and desperate, but counting his blessings because he has a Dalmatian, just enough drugs, and solid guitar technique. There is no real reason why there should be a 10-second solo in the first 45 seconds, but it works perfectly. It’s the way Nowell’s vocal drops out to sample “Life Is … Too Short.” It’s the way “charity” feels mixed from a distant echoing dimension. It’s the hook straight from Half Pint’s “Loving” and the bridge that feels effortlessly natural but scientifically designed for arena sing-alongs.

I don’t cry when my dog runs away

I don’t get angry at the bills I have to pay

I don’t get angry when my mom smokes pot

In the same way that RZA was lifting ’70s soul hooks, comedy routines, and Stax samples to rebuild Wu-Tang into its own dusted constellation, Sublime plundered their own crates and memories. On “What I Got” alone, there are samples from Richard Pryor, LL Cool J, the Fugees, and the aforementioned Too Short and Half Pint nods. The melody warps the Beatles’ “Lady Madonna” into something ready-made to be blared from the sub-woofers of pickup trucks. If 40oz. to Freedom was their counterpoint to Paul’s Boutique, this was their Check Your Head, a freewheeling ensemble of mutants reanimating the skeletons buried in wax, replaying classic lost sounds live and relighting the spliffs for the saints.

“That was the sound that we were striving for all along, and we finally got to where we were going with that sound,” Gaugh says. “We wanted to be like the Beach Boys or Bob Marley, and we just weren’t quite there yet, and then we finally made it, and then it was like fuuuck.”

What’s so astonishing is how well Sublime worked as pop. For all the vulgarity, eccentric mid-song tangents, and time shifts, it spent three and a half years on the Billboard album charts. As long as there are malls with PacSun and Volcom stores, as well as tiny surf shops worldwide, it will remain in rotation. But whenever you try to reduce it to lifestyle music, there is always something more. Nowell was one of the truly magical singers, versatile enough to shift between hardcore mosh pit snarls to beatific reggae lilts, Spanish ballads, and melodic rap rants. His voice could be astonishingly tender and fragile or curl into a clenched fist. On “Pawn Shop,” Nowell summons a bleary workingman’s blues, the faraway shadow of his vocals about to vanish into the sun-smoked air.

“The guy could really sing. He was a natural,” Leary says. “If he had lyrics written out or if he was freestyling, he was gonna sing great. You didn’t have to pound it or anything. The same with his guitar.”

It’s easy to overlook the sheer tightness of the band, bound by thousands of shows and best-friend arguments. In different permutations, Nowell, Wilson, and Gaugh had been playing with each other since their teen years. The album is understandably filled with small moments where Wilson’s and Gaugh’s virtuosity shine. The balletic switch on “Same in the End” when it goes from headbanger’s ball to a nimble darting bass line and booming drums that sound like they’re about to incite a drag race. Or “Seed,” where they effortlessly shift speeds three times in the first 15 seconds, flawlessly absorbing the lessons of Bad Brains.

“Brad was the older brother and would fuck with Eric sometimes and Eric would get pissed, but they were connected in some fucking strange way,” says Opie Ortiz, who designed most of the band’s art and covers. “Eric was Brad’s right hand, and Bud was his left hand. He needed them to do this Sublime thing.”

In the end, posterity relies on the songs. Without them, Sublime would’ve been 311, the Aquabats, the Mighty Mighty Bosstones, or any of the other bands skanking around at the time, competing for precious MTV airplay. It’s why Sublime With Rome can continue to sell out theaters across the United States with only a single member of the original band (Wilson) and a lead singer originally from the East Bay, who was 7 when Bradley died. Sublime may not have a catalog remotely as deep as the Dead, but to their acolytes, a song like “Santeria” carries as much weight as “Friend of the Devil” does to someone with a wardrobe full of Organic Ceramics.

Sublime is its own modern songbook: a sensitive, vile, and oddly relatable batch of songs so infectious that they have been covered into oblivion by everyone from raggedy Gaslight District buskers to Lana Del Rey and Post Malone. There is “Wrong Way,” the preposterous tale of Nowell’s attempt to save a young girl cast into sex work by her monstrous father (Wilson estimates it’s about half-true). “April 29, 1992 (Miami)” is the best song written about the L.A. riots this side of Death Row Records. “Santeria” is a classic jealous lover lament as timeless as “Waiting in Vain.” And look, there are many things about “Caress Me Down” that have aged poorly, not least of all the Ron Jeremy reference in the first few seconds; but it functions as the band’s own version of “Ain’t No Fun (If the Homies Can’t Have None),” except fluently bilingual, self-deprecating, and oddly sweet. A scumbag with a heart of gold.

The album’s finale and last single, “Doin’ Time,” has long since staggered into the BBQ-drunk pantheon of Southern California summertime anthems, alongside cuts like “Summertime in the LBC” and “Pitch in on a Party.” But like the latter, “Doin’ Time” washes up with a dark undercurrent that defies the “living’s easy” mantra, which exists as red herring. It’s a woozy jeremiad about the love of his life, whose constant infidelties leave him comtemplating murder. It’s a lethal beachfront blues, but the beauty of the melody and the eerie, demonic trip-hop makes you think he’s going to celebrate his success by drowning himself in the ocean. And there’s a fictional element that upends the narrative that everything Nowell wrote was straight autobiography. At the time of its composition, he was as close as he’d ever come to domestic bliss, the father of a newborn son, living with his soon-to-be bride. He had perfected the art of the exceptional first-person writer: where you readily accept that every detail is 100 percent truth.

“Doin’ Time” distills the furtive intricacy of the band’s method. It’s built off a sample of Herbie Mann’s “Summertime,” a bossa nova cover of the George Gershwin jazz standard. Ras MG deploys a 1/16th note reggae drum beat, and the band flip samples of the Beastie Boys’ “Slow and Low,” Ini Kamoze’s “Jump for Jah,” Malcolm McLaren’s “Buffalo Gals,” Lou Donaldson’s “Ode to Billie Joe,” and David Axelrod’s “Holy Thursday.” But it could have been done well only by Sublime, who in their omnivorous attack soaked up G-funk, hybridized it with punk, jazz, and reggae, and set the foundation for remixes from the Pharcyde and Wyclef Jean. The most iconic was the Snoop Dogg “Doin’ Time” bootleg, which found their old neighbor cosigning the assessment that they were well qualified to represent the LBC. For a period of several summers, it was inescapable on both KROQ and the city’s then-biggest hip-hop station, Power 106, a crossover achievement matched only by Cypress Hill. It spoke to the universality of Sublime’s charm. For a micro-generation who first discovered music via gangsta rap, grunge, and the Chili Peppers, Sublime seemed like the logical inheritors to that legacy. Soon enough, nu-metal would emerge and eradicate all traces of the musical nuance that Sublime wielded. Hip-hop would bifurcate into the jiggy mainstream and the purist underground, but in the interregnum, Sublime sat on the throne. The only problem was that there was no chance of producing a successor.

That’s not to say that no one tried. In the wake of Sublime’s mass appeal, Wilson, Gaugh, and Ras MG formed the Long Beach Dub Allstars (which Opie Ortiz would later front). For most of the next decade-plus, every festival where there was at least one booth petitioning for the legalization of hemp (among other things) booked no fewer than six Sublime knock-off bands. Slightly Stoopid, the band that Nowell signed to Skunk when they were still in high school, have sold millions over the years. Nearly every band since ’96 that has attempted to alchemize hip-hop, punk, ska, dancehall, and roots reggae exists squarely in Sublime’s debt. Some racked up billion-streaming singles like Magic!, others are like Pepper, lesser known to mainstream audiences, but able to sell out a show on any given night in Humboldt County. Beyond having Sublime as their big-bang influence, most of the imitators are united by being largely awful soundtracks for hacky-sack, ideal for acid casualties attempting to sell amateur metallurgy outside of a String Cheese Incident concert.

There are those who would say that this is evidence of Sublime’s ineptitude, but it’s actually the strongest case to the contrary. Sublime are a creative dead end, not a jumping-off point. On paper, every one of their ideas reads terribly. Sure, OK, let’s get three white punks from Long Beach and have them sing Toots and the Maytals and Grateful Dead covers. There will be hymns of praise to KRS-One and sometimes the lead singer, yeah, he sings in Spanish. No, he grew up fairly well-off.

But it’s testimony to Nowell’s genius that he not only pulled it off, but that a quarter-century later, their songs remain relevant enough that two summers ago, this publication declared a “Sublimeaissance.” If you ask anyone who was once close to Nowell, they’ll readily give you several preposterous anecdotes about his trickster humor. Some are best left unsaid. But if you keep asking more about who he was, they’ll inevitably tell you how they never met anyone like him. They’ll talk about his shy, quiet, and vulnerable streak, his radiant intelligence, and how even during his most fargone episodes, he was rarely without a book. Before he died, the plan was to tour Europe, and Nowell had already stocked up on a miniature library of European history. He was a regular at the Jeopardy! night at one of the bars on Sunset Beach, and his widow remembers him knowing every answer, whether it was about World War II or Himalyan topography.

“He was the smartest stupidest person that I’ve ever met,” Dendekker says, laughing.

But even this afforded him an accessibility that contributes to his legacy. There is no pretense nor affectation to Sublime’s music: It’s for everyone, without being so watered down that it’s actually for no one. You don’t see Nowell on dorm room posters or in Venice Beach souvenir kiosks to the same extent that you see 2Pac or Kurt Cobain. It’s partially because Sublime’s catalog is leaner, but I suspect that it also has to do with the fact that he lacks that shape-shifter component that allows people to interpret them in any ideological way that they prefer.

Bradley was just Bradley, the regular dude blessed with extraordinary talent. He wasn’t the myth you build a shrine to, he was the dead homie airbrushed on a T-shirt, forever mourned but remembered with a smile. He just happened to be a voice for those more comfortable speaking in curses. The love-seeking ringleader of Sublime; there could never be another one like them, which is probably a good thing.

Jeff Weiss is the founder and editor of POW. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and GQ.