In a late-August game against the Nationals in New York, Mets reliever Aaron Loup learned the futility of trying to tempt Juan Soto. Leading off the sixth at Citi Field with the Nats trailing 4-2, Soto swung and missed at the first pitch from Loup, which appeared to catch the corner up and in. Then he fouled off a second sinker slightly farther inside. After falling behind 0-2 to southpaws this season, left-handed hitters have slashed just .164/.191/.247. Soto was about to beat those odds.

Loup tried a third consecutive sinker, this time trying to paint the outside corner. It was close, and most hitters would have felt pressure to protect the plate: On 0-2 counts, left-handed hitters swing at roughly three-quarters of pitches in that approximate location. Soto spat on it instead, then launched into an understated version of the Soto Shuffle, the ostentatious post-take routine that’s unique to the Nationals slugger. He lifted and tapped his front foot as if replaying and retroactively timing the pitch he’d just seen. His right arm, still forming a right angle at the elbow, detached from the bat and swung forward as his back foot raked the batter’s box like the hoof of a bull about to charge. Then he stared out at Loup as if to say, “I see through you.” Finally, he hitched up his pants, bat-tapped a toe, and prepared to step in again.

The next pitch was low and slow, a cutter that swept from one batter’s box to the other. Soto watched it sail outside. This time, he kept crouching and tapped his front foot three times before sweeping with the back leg. Loup was messing with the bull. Soon Soto would give him the horns.

Perhaps you’ve heard the (apocryphal) story about the dinner guest who bet she could get more than two words out of Calvin Coolidge, only for Coolidge to tell her, “You lose.” Trying to coax three chases out of Soto is a little like that. You might get him to go outside the zone once or twice in a single plate appearance, but if you’re counting on Soto to help strike himself out, then like Loup, you’ll likely lose. Having failed to convince Soto to swing at a ball with two strikes, Loup left his fifth pitch out over the plate, and Soto smacked it over the fence in left-center. This time he shuffled all the way around the bases.

Although the solo shot proved inconsequential—the Mets wound up winning 9-4—it capped the quintessential Soto plate appearance, one in which he used his power, his plate discipline, and his Shuffle to full effect. I can confidently call it quintessential, because I’ve seen at least a snippet of almost every Soto trip to the plate this year. From the Nationals’ season opener on April 6 through Sunday’s game, Soto took 1,383 pitches, more than any other National League player. I watched him watch every one of them in an effort to understand when, where, how, and why Soto’s signature Shuffle occurs. I also saved the visual evidence. Feast your face on this sitcom-length Soto Shuffle supercut.

Before we dive deep into Shufflemetrics, let’s establish why you should care about Soto’s idiosyncrasies. Although the going-nowhere Nationals surrendered at the trade deadline, dealing Max Scherzer and Trea Turner to Los Angeles for four prospects—each of whom is older than the 22-year-old Soto—this is otherwise a fine time to fixate on the team’s sole remaining superstar, who was batting .300/.446/.517 through Sunday. Soto walked twice in that same late-August game against the Mets, accounting for two of the 33 free passes he drew during one of the walkiest months in history.

Only a select list of laser-eyed everyday players, highlighted by legends such as Barry Bonds, Ted Williams, and Babe Ruth, have walked in more than 30 percent of their plate appearances in any given calendar month, as Soto did in August. Famed from the start for his selectivity, Soto has recently reached plate-discipline nirvana, offering at fewer than 9 percent of pitches outside the zone over an extended stretch of games—less than a third as often as this season’s 27.5 percent MLB-average rate. The rarer his chases, the more frequent his walks. “Whenever [pitchers] want to play, I play,” Soto said last month. “When they don’t want to play, I just take my walk.”

Given that middling cleanup hitter Josh Bell commonly bats behind him, one might surmise that Soto’s free-pass hike has to do with a lack of lineup protection. Even though the surprisingly potent Nats offense has boasted the best non-pitcher production of any NL team in the second half, it’s a low-profile group outside of Soto, who for the second straight season is leading the majors in intentional walks. (Entering Sunday’s game, Soto had drawn more walks of any kind in 2021 than the rest of the Nationals’ starting lineup combined.) But Soto has seen pitches inside the strike zone at a career-high rate, possibly because pitchers have given up on trying to fool or fluster him with waste pitches.

Soto’s full-season walk rate of 20.9 percent entering Monday matched his rate in nearly 200 plate appearances last season. No qualified hitter has walked that often since Bonds in 2004. Relative to the league average, Soto’s on-base percentages of .490 and .446 in 2020 and 2021 (through Sunday), respectively, are among the 35 best by a qualified hitter in the expansion era. His 167 wRC+ since the start of 2020 easily leads all players with at least 400 plate appearances over that span, and he’s the only hitter with 150 plate appearances this season who’s walked more often than he’s struck out. No hitter this season has racked up more run value by taking pitches, especially in the area surrounding the strike zone that MLB labels the “Chase” region. Not only has he spit on pitches outside the strike zone more often than any other qualified hitter this year, but his 5.0 ratio of in-zone swing rate to out-of-zone swing rate—a sign of smart, selectively aggressive swing decisions, rather than a refusal to swing at all—dwarfs the second-place player’s (Tommy Pham at 3.9). In the 2008 to 2021 pitch-tracking era, only Joey Votto, at 5.6 and 5.2 in 2018 and 2017, respectively, has had a higher single-season ratio.

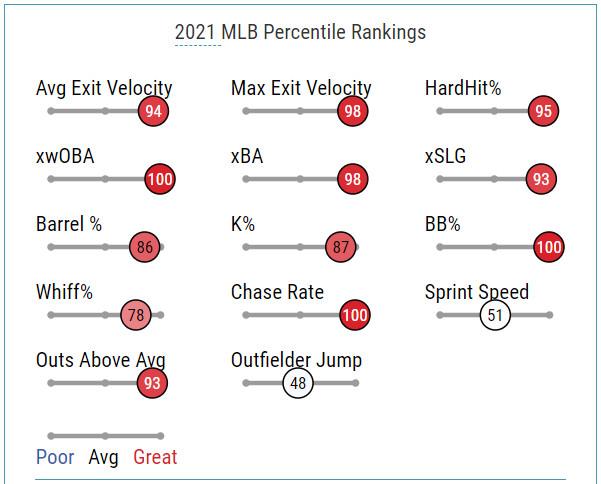

No one spits like Soto, no one hits like Gaston Soto. Partly because he swings almost exclusively at strikes, he tends to blister the ball when he makes contact, as he demonstrated during his Home Run Derby showdown with fellow hard hitter Shohei Ohtani. Soto started slowly (by his standards) this season, posting a 128 wRC+ prior to the All-Star break thanks to a spike in ground ball rate, but he held out hope that the Derby would fix his swing. Whether the Derby did the trick or regression righted what ailed him, his grounder rate plunged post-break, which has helped him lead all players in wRC+ and FanGraphs WAR in the second half. A glance at Soto’s Statcast percentile rankings via Baseball Savant confirms that he has no weak point. Except for his speed, which is only average—a fact he wouldn’t dispute—Soto is an all-around scale-topping talent. Even his defense, which rated below average on the whole over his first three seasons, per a trio of defensive metrics—DRS, UZR, and OAA—has gotten good grades this season, his first as a full-time right fielder.

Soto’s power and newfound defensive capacities are somewhat overshadowed by his signature skills: his otherworldly walk rates, and his ability to let balls go by, two traits that typically peak in a player’s late 20s or early 30s. He easily leads the majors in walks since May 20, 2018, when he made his big league debut (excluding the suspended game from May 15, 2018, that he technically took part in “before” he made the majors):

Most Walks Since Soto’s Debut

Soto, who’ll turn 23 in late October, is younger than the game’s consensus top prospect, Orioles catcher Adley Rutschman, but his precocious play put him on a Hall of Fame trajectory even before this season started. Soto’s 18 percent career walk rate leads all AL or NL hitters with at least 1,000 plate appearances through their age-22 season, and he has a shot at topping Mel Ott (who debuted a good deal younger than Soto) for the most walks drawn prior to a player’s age-23 season.

Most Walks Through Age 22

In The Science of Hitting, Ted Williams expressed the misleading old saw that “even if you are a .300 hitter … you are going to fail at your job seven out of 10 times.” As Williams well knew, though, the hitter’s goal is to get on base, and if a hit isn’t handy, a walk will do. Not only is Soto a .300 hitter who fails at his job a lot less often than seven out of 10 times—unlike Alcides Escobar, who usually bats ahead of him and who in nearly 6,000 career plate appearances has made outs more than 70 percent of the time—but he’s following Williams into rarefied territory where failure is roughly as likely for the pitcher as for the batter. Soto’s walks would be a marvel—albeit a boring one—if he simply stood still in the batter’s box until it was time to take his base. But few players are as fun to watch when they do swing as Soto is when he doesn’t. He’s the game’s most judicious and prolific pitch-taker, and he’s its most entertaining taker, too.

The Soto Shuffle first made national news in October 2019, when non-Nationals fans who were watching Washington’s journey to a title discovered that Soto wasn’t just great at baseball, but also great TV. If The New Yorker’s Roger Angell had still been blogging about baseball that fall, he could have deployed his descriptive skills, honed in the days before MLB.tv (and, for that matter, traditional TV) to deliver the most evocative verbal sketch and the perfect, forgotten player comp for Soto’s seemingly singular mannerisms. Those of us who were not in our 90s lacked the necessary reference points, especially if we were steeped in the post–Tom Emanski ethos of mass-produced motions, stances, and swings—what the writer Matthew Trueblood has called a “creeping homogeneity” and a “stylistic blending that’s leading to probably fewer of those really quirky guys, or more guys who seem to have this very engineered swing, the very compact pitching mechanics.”

As an antidote to that perceived sanding-down of aesthetic eccentricities, and a means of “preserving that biodiversity within baseball,” Trueblood recommended chronicling and celebrating tics instead of “immersing ourselves in the hyperfocus on efficiency that can sap some of the joy from the game.” Soto’s style is both ultraefficient and gloriously strange. Some players take pitches passively. Soto takes pitches aggressively—greedily, even. He’s having a conversation with the pitcher, a dialogue conducted in body language.

The Shuffle, as spellbound baseball fans learned in late 2019, began when Soto—a highly touted prospect, though not nearly hyped enough—was quickly climbing through the minors. (He hit .362/.434/.609 across parts of three seasons before being promoted to the majors from Double-A.) It was, he insisted, a timing mechanism. But it was also a manifestation of the justifiably self-assured phenom’s “my batter’s box” mentality. “I like to get in the minds of the pitchers,” he said. “Because sometimes they get scared.” Another quote from that fall: “It’s a fight, just the pitcher and me. I forget about everybody that’s around me—I just think of the pitcher and me.”

One might imagine that the Shuffle could influence the umpire, but it doesn’t seem to: According to calculations performed for this piece by Jonathan Judge of Baseball Prospectus, Soto hasn’t received significantly more (or fewer) calls in his favor than one would expect based on the characteristics of the pitches he’s seen. His gyrations may help him psych himself up and could conceivably intimidate his opponents, but umpires seem immune to the Shuffle’s charms. Similarly, despite the oft-repeated tale of umpires deferring to Williams’s sense of the strike zone—“Mr. Williams will let you know when you have thrown a strike, ”one ump supposedly told a pitcher—there’s scant evidence that they were notably biased toward him. Hitters like Williams and Soto—not that there are many hitters like them—know the difference between balls and strikes, but they probably can’t turn one into the other.

Regrettably, Soto no longer pointedly adjusts his junk between pitches, as he routinely did in 2019. Perhaps it’s a concession to the sensitivities of other players. (During the 2019 NLCS, Cardinals pitcher Miles Mikolas retaliated with a junk adjustment of his own.) Maybe he considers the crotch grab conduct unbecoming of a 22-year-old. Or maybe, after a championship, multiple appearances in MVP voting top 10s, and a Silver Slugger award, he knows his performance speaks for itself. Regardless, the good news is that he’s still no normal hitter. A complete classification of Soto’s non-swings would take a team of taxonomists weeks to sort out, but consider a few moves from this season that can’t be confused with the off-the-shelf Shuffle. For instance, the one where he takes a close pitch, spins so that his back is facing the pitcher, and then hops in place anywhere from once to 4.5 times. If Soto were a skateboarder, we could call it an ollie.

There’s the variation on the ollie where instead of hopping, he waggles his butt.

And there’s the one where he lunges and holds his pose.

Sometimes Soto performs a pirouette.

Sometimes he smiles and nods to acknowledge nice pitches.

He’ll adopt a dramatic pose or recoil and revolve to sell a checked swing, or bend out of the way of pitches that aren’t that far inside. He’ll laugh at premature strikeout celebrations and converse with the catcher. And, of course, he’ll Shuffle, though no two Shuffles look exactly alike. The Shuffle, I discovered, is a spectrum. Soto chains combos of the Shuffle’s component parts, but the ingredients differ depending on the pitch: the slide, the sway, the stare, the thigh pound. He might toe-tap once, or he might toe-tap five or six times, swaying like a cobra in a snake charmer’s thrall.

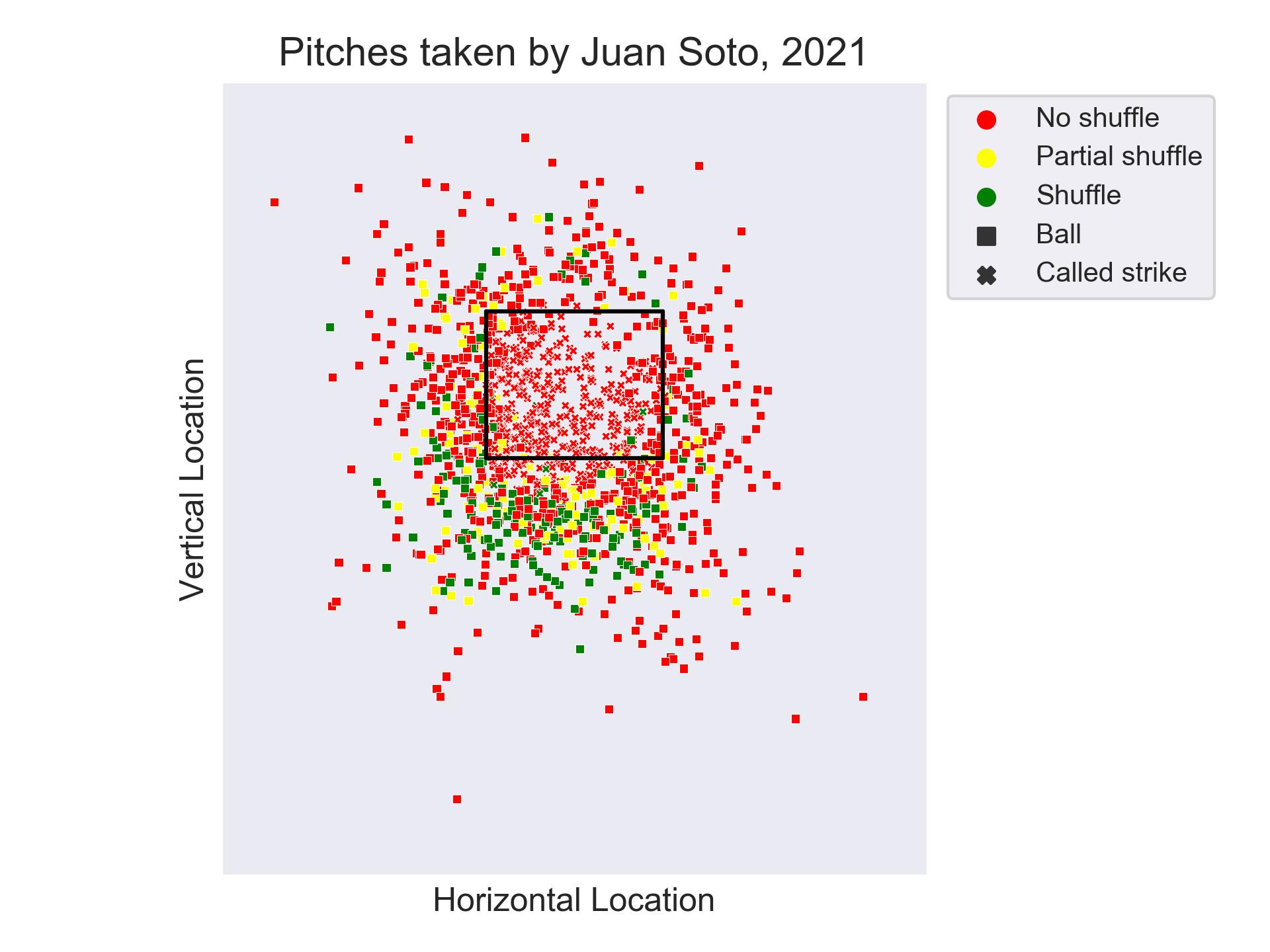

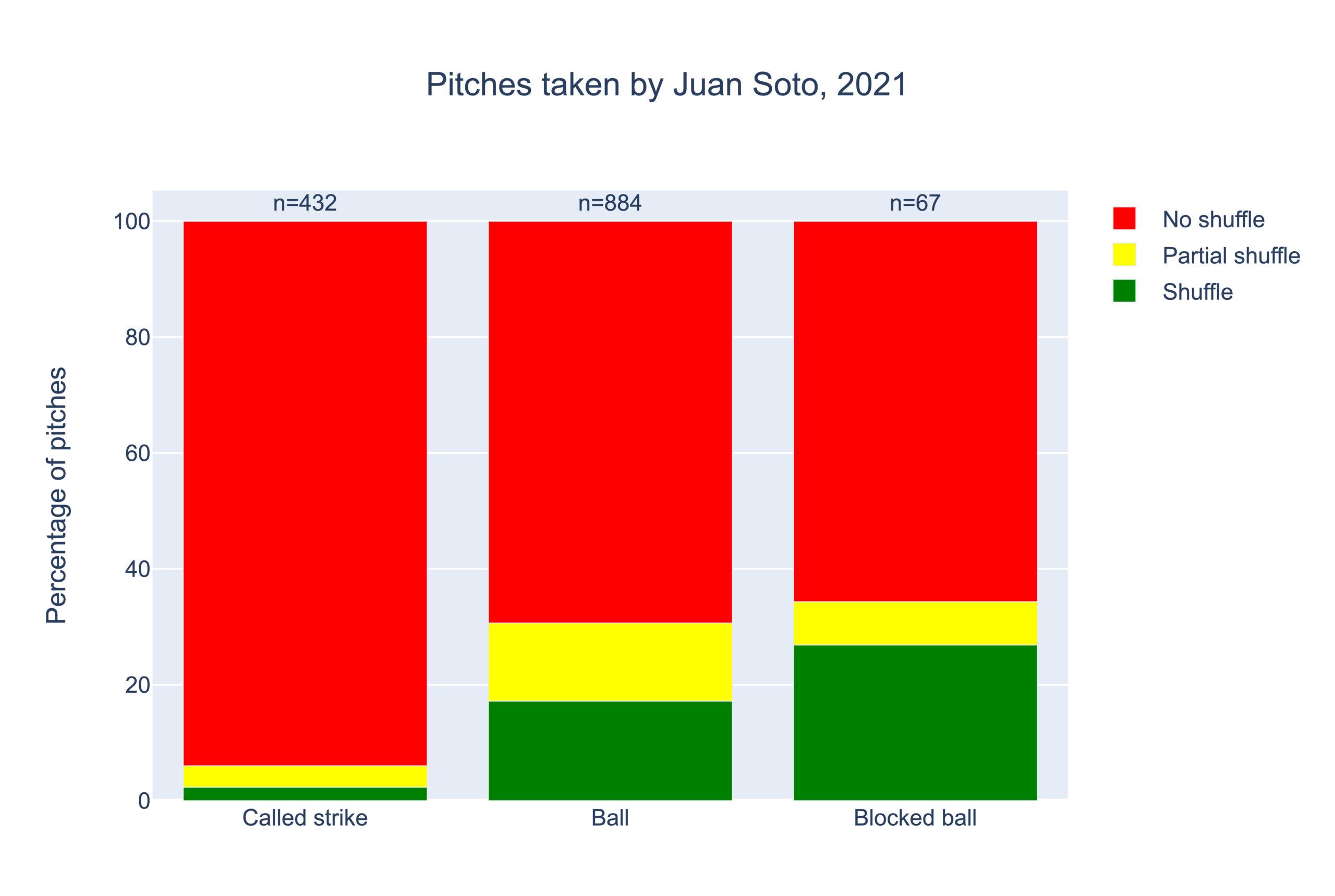

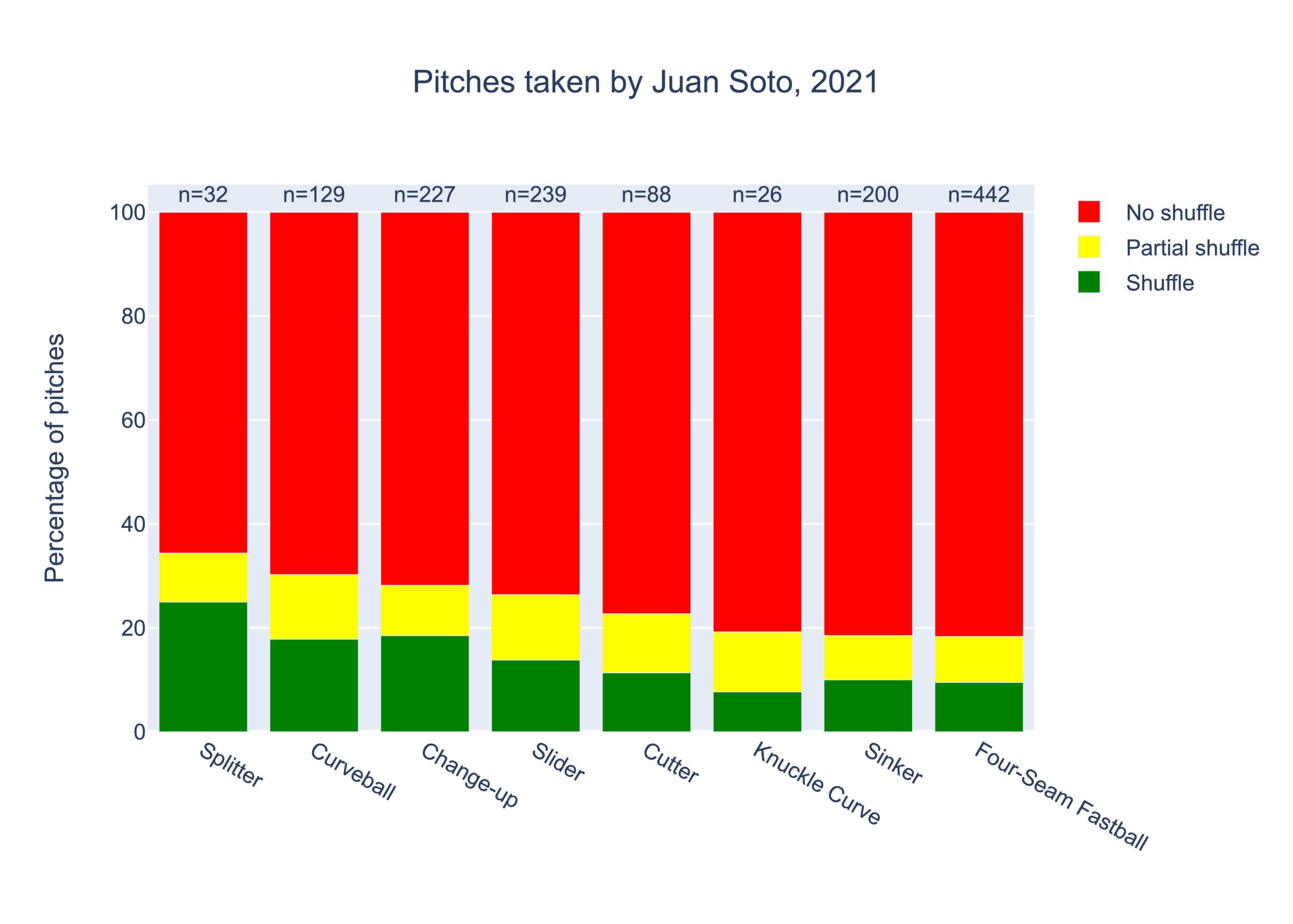

In the end, I went with three categories—Shuffle, partial Shuffle, and no Shuffle—using the Justice Potter Stewart approach to distinguish between them. Out of those 1,383 takes, 1,063 (76.9 percent) were Shuffle-free, 180 (13.0 percent) were Shuffles, and another 140 (10.1 percent) were partial Shuffles. All of the pitches (and ball-strike calls) are superimposed below on an approximation of Soto’s strike zone, with Shuffle classifications color-coded according to a traffic-light scheme: green for a Shuffle, yellow for a partial Shuffle, and red for a non-Shuffle.

Soto is unlikely to launch into his elaborate post-pitch routine on pitches inside the strike zone: He Shuffled (or appeared to start Shuffling) on only 10 called strikes and eight pitches with a called-strike probability (according to Baseball Prospectus) of more than 50 percent. As the pitch plot makes clear, Soto is much more likely to Shuffle (and partially Shuffle) on low or inside pitches than on high or outside pitches, and he’s more likely to Shuffle on blocked balls than on balls that are caught cleanly.

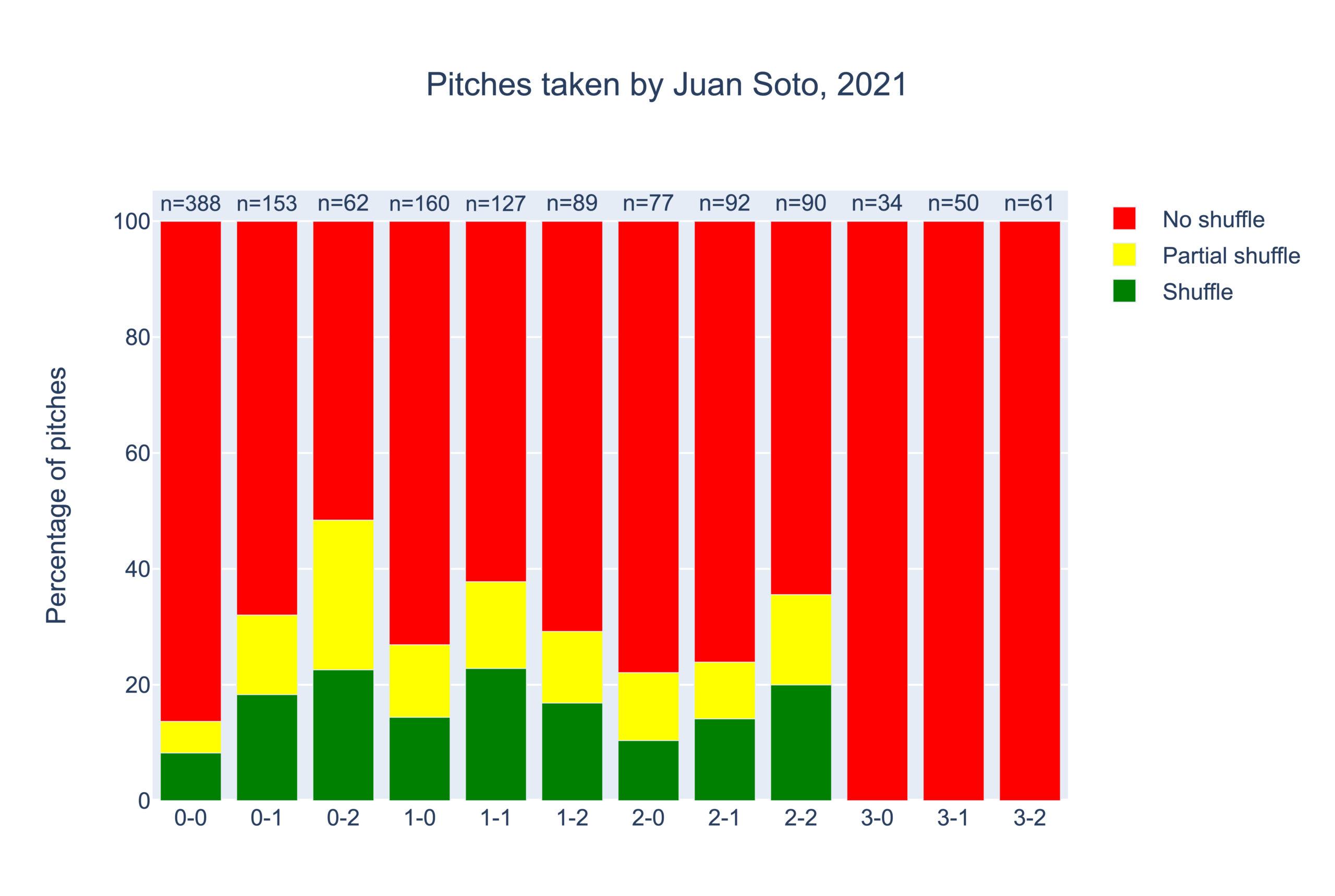

Because Soto Shuffles only on pitches he believes to be balls, he never Shuffles with a three-ball count. He Shuffles fairly frequently when the count is 1-1 and on two-strike counts (except for full counts), with his peak Shuffle rate reserved for 0-2 offerings like the two against Loup that led off this article.

On the violin plot below, the most bulbous sections represent points on the scale of called-strike probability where Soto is most likely to Shuffle, partially Shuffle, or restrain himself from Shuffling. Non-Shuffles abound on near-certain strikes and near-certain non-strikes, whereas partial and full Shuffles cluster toward the neighborhood of unlikely (but not impossible) strikes. The locations of pitches that prompt partial and full Shuffles largely overlap, but the latter tend to be slightly farther from the zone. (A box plot tells the same story, as do violin and box plots of Soto’s post-pitch rituals as a function of distance from the center of the zone instead of called-strike probability.)

Given that Soto is most prone to Shuffles on low pitches, it follows that his highest Shuffle rates would be against breaking balls (and, by extension, slower pitches).

Soto is one of the game’s best fastball hitters: Only Vladimir Guerrero Jr. has generated a higher run value against four-seamers this season. Soto has also been above average against sinkers and cutters, compared to only average against sliders and curveballs combined. Thus, when he Shuffles, he may be reminding himself to lay off the pitch types that give him the hardest time, and that tend to make a beeline for the low-and-in locations where he’s historically struggled to drive the ball.

When Michael Lewis wrote about four-time AL walks leader Jason Giambi in Moneyball, he noted that the patient slugger’s self-control made it “nearly impossible for even a very good pitcher to do what he routinely does with lesser hitters: control the encounter.” Hitting is inherently a reactive activity, and no hitter’s reactions are more exaggerated than Soto’s. But Soto’s post-pitch theatrics are a sign that he’s setting the tone.

Dating back to the days when balls and walks weren’t even recorded, on-base abilities have been underappreciated and underpaid. Aside from the odd montage of Votto trotting to first, no one creates highlight reels of hitters opting not to swing. The Shuffle makes Soto an exciting exception. He’s an artist of the strike zone whose canvas is the sport’s expanding negative space, measured in time between pitches. And of his many accomplishments, this may be the most inimitable: He’s managed to make takes cool.

All stats except Soto’s career walk totals are through Sunday’s games. Thanks to Harish Swaminathan for data visualization assistance and to Lucas Apostoleris and Jonathan Judge of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.