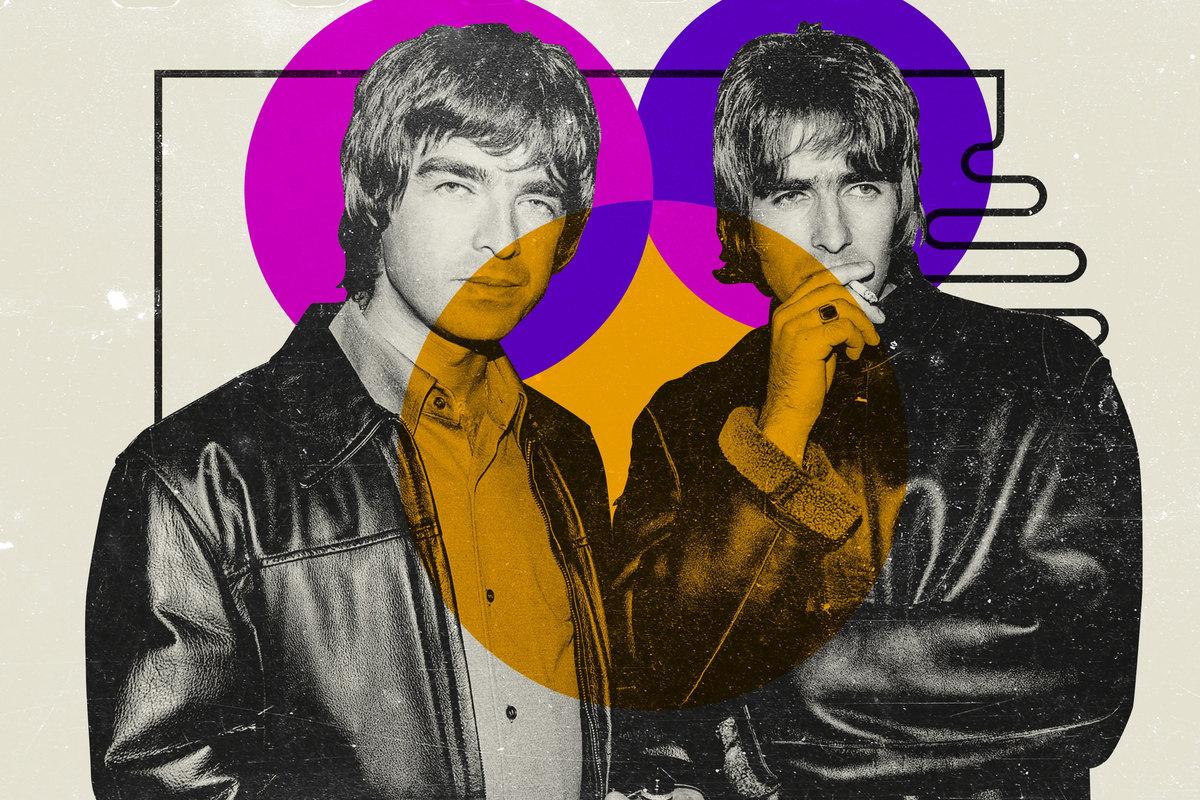

Grunge. Wu-Tang Clan. Radiohead. “Wonderwall.” The music of the ’90s was as exciting as it was diverse. But what does it say about the era—and why does it still matter? On our show 60 Songs That Explain the ’90s, Ringer music writer and ’90s survivor Rob Harvilla embarks on a quest to answer those questions, one track at a time. Follow and listen for free exclusively on Spotify. Below is an excerpt from Episode 41, which breaks down Oasis and their biggest hit, “Wonderwall.”

The first Oasis single is called “Supersonic.” Comes out in April 1994. Dig those vowels. Dig that riff. Dig the arrogant, radiant dirge of it all. The guitars on early Oasis songs, man. Guitars, plural; guitars innumerable. Just this rad boorish pervasive malevolent GHHHHHHHGGGGHH sound engulfing everything. “Supersonic” is rock ’n’ roll personified. “Supersonic” is a legit Where Were You the First Time You Heard This situation. Take, for example, Lars Ulrich. Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich. Lars has rhapsodized about Oasis, about “Supersonic,” for 25 years. Lars worked the lights at an Oasis show once. True story. Lars wrote a thing for The Guardian in 2014 about discovering his favorite band, Oasis. First he talks about paging through an English magazine called Select, and he says, “There was a story about a band from England, with some unusual looking fellows, that I’d never heard of. I skimmed across the article, and was quite amused by the fact that every other word was either fuck or …” well, the C-word. He says, “It reeked of attitude and not giving a fuck, which at the time—at the height of the shoegazing-I-can’t-handle-being-a-rockstar attitudes that were becoming mainstream—was very refreshing.” As for “Supersonic” itself, Lars heard it for the first time on San Francisco rock radio station Live 105; he says, “The attitude, the aloofness, and the not-giving-a-fuck vibes were pouring out of the speakers.”

I’m feelin’ supersonic

Gimme gin and tonic

You can have it all but how much do you want it?

Ask me how charming I find this image, of Lars Ulrich, the Derek Jeter of drummers, tooting across the Bay Bridge in his sensible economy car, there’s a Basquiat he just bought in the back seat, he’s sipping a Neapolitan milkshake from In-N-Out Burger—secret menu—and headbanging along to “Supersonic.” I love this. I am immensely charmed by this. This is the essence of rock ’n’ roll to me. I am a connoisseur of Lars Ulrich raving about songs. There’s the famous story—it’s famous to me—that Lars tells about being on a plane and listening to a cassette of Appetite for Destruction by Guns N’ Roses for the first time, and Lars freaks out when he hears “It’s So Easy.” He says, “It just blew my fuckin’ head off. … It was so fucking real and so fucking angry.”

Why do I remember stuff like this? I guess I get excited when Lars gets excited. I give a fuck when Lars gives a fuck about people who don’t give a fuck. Oasis, quite blatantly—you might say thirstily—wanted you to think they were the Beatles. And they were, almost, for a couple years there, but to my mind that’s not their true lineage. Here’s your true lineage: Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, and Oasis.

So. Oasis in 1994. Who are Liam and Noel’s worthiest adversaries? I would like to heartily recommend to you the book Britpop! Cool Britannia and the Spectacular Demise of English Rock. First came out in 2003. Written by the British journalist John Harris. This is a rad book. This is a blunt book. Spoiler alert: An Oasis album actually causes the spectacular demise of English rock. Liam and Noel giveth, and Liam and Noel snorteth away. So here, of course, primarily we’re talking Oasis, Blur, Suede, Elastica, and Pulp. (Book’s a little light on Pulp, actually—I listened to This Is Hardcore an hour ago, it was fantastic—but I already raved about Pulp’s “Common People,” one of the best songs ever. Pulp rules, I think we’ve established this.)

You know why this book is rad? It’s not just the Gallaghers. Every major band that drove the ’90s Britpop boom is absurdly quotable. Just saying ridiculous shit, talking just the wildest shit imaginable at all times. Everybody. English rock stars make American rock stars sound like Bill Belichick. Shoegaze is another guitar-rock subgenre from the U.K., of course: My Bloody Valentine, Ride, Slowdive, etc. But when Lars rails against the downer I-can’t-handle-being-a-rockstar vibes that bummed him out in the early ’90s, I think he means grunge—I think he means Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, even Nirvana. All that self-loathing. It gets old. I’m so bored with the USA. You know what I like, in a rock band? Regular loathing. Loathing of others. Loathing of other bands, if not whole other countries. What exemplifies, what unifies Britpop for me is not the guitars; not (mostly) the bros, the broishness; not the wounded narcissism; not the accents. It’s the aspiration. It’s the arrogance. It’s the audible, tangible will to conquer. Every Britpop band sounds like they’re trying to conquer Britain, and then lead Britain to conquer the rest of the world. Call it Manifest Destiny if you want.

Britpop was lousy with adversaries; that was the whole point. But Oasis crushed them all. Oasis conquered. The Gallagher family grew up in a suburb of Manchester called Burnage. You can find their modest childhood home on tourist sites on the internet, if you’re looking to visit in person, one site advises, “Please be discreet due to the current neighbourhood.” I can’t tell if that means Don’t bother anyone currently living there or Everyone currently living around there will beat the crap out of you. Maybe both! Manchester is a northern city, a somewhat gray and industrial city, a historically culturally vibrant city. Manchester is the Detroit of England. Ugh. That’s even worse. The Gallaghers, Peggy and Tommy, were Irish immigrants who had three boys: First came Paul, then Noel, then Liam. The Gallagher brothers talk quite a bit about how their father, Tommy, was physically abusive, both to their mother and at least to Noel; Noel, who was obsessed with music from the start, would later say, “I guess in some way my fella beat the talent into me.”

Liam, for his part, as a surly teen was more outgoing, more popular, more handsome, more aloof; Paul, his other older brother, tells a story about a gang fight at school where Liam and his crew were ambushed, essentially, and someone “boshed Liam on the head with a hammer.” Boshed is bad; bopped is good. But Liam says from that day forward, something clicked. He started hearing music. It started making sense. Noel says, “Someone hammered the music into him.” Music, to both these guys, is inextricable from violence. It is the cause, and the effect, of great personal violence.

To hear the full episode click here, and be sure to follow on Spotify and check back every Wednesday for new episodes on the most important songs of the decade. This excerpt has been lightly edited for clarity and length.