Amid MLB’s anticlimactic tiebreaker tease on Sunday, the Los Angeles Angels played a game with playoff implications. Just not, you know, playoff implications for them. The Angels were eliminated from postseason contention on September 21, but they posed successfully as spoilers over the regular season’s closing weekend, downing the Mariners 7-3 in Game 162 to take two of three from the M’s. Despite dousing their run-differential-defying division rival’s hopes of an elusive playoff appearance, the Angels finished 77-85, giving them their sixth consecutive losing record and fourth consecutive fourth-place finish in the AL West. All of which means that even though MLB’s postseason is starting on Tuesday, Shohei Ohtani’s season is already over.

Early exit notwithstanding, 2021 was and always will be the year of two-way Ohtani. Ohtani’s exploits as a full-time hitter and roughly full-time pitcher prompted comparisons to pre-integration greats such as Babe Ruth, Bullet Rogan, and Martín Dihigo, but no major leaguer—let alone a major leaguer facing something close to current competition—has ever combined power hitting, power pitching, and speed at the level and volume that Ohtani did in 2021. With a leadoff homer and two walks on Sunday, Ohtani closed the book on his singular campaign, allowing us to size up his exquisite stats in their final form.

Let’s start with the basics, offense first: Ohtani, who turned 27 in July, batted .257/.372/.592 in 639 plate appearances, good for a 152 wRC+ (150 vs. righties, 154 vs. lefties) that ranked fifth among qualified hitters. He hit 46 home runs, placing him third in the majors behind Salvador Perez and Vladimir Guerrero Jr., who tied for first with 48. His 80 extra-base hits were the second most in the majors behind Marcus Semien’s 86. He stole 26 bases, which ranked eighth in the majors, and he led the American League (and tied for the major league lead) with eight triples. He led all players (minimum 250 balls in play) in barrel rate, and he finished in the 97th percentile or higher in average and max exit velocity, hard-hit rate, and walk rate.

As a pitcher, Ohtani compiled a 3.18 ERA with 156 strikeouts in 130 1/3 innings. Among the 79 pitchers who threw at least 130 innings, he ranked ninth in opponent batting average, 11th in strikeout rate, 14th in strikeout rate minus walk rate, and tied for 14th in park-adjusted ERA. He hit as many homers as he allowed earned runs. Thanks to his productivity on both sides of the ball, Ohtani was an All-Star twice over, and he led the majors in both Baseball-Reference WAR (9.0) and FanGraphs WAR (8.1).

By filling up so many stat columns that players typically leave empty, Ohtani earned entrance to several exclusive clubs based on gerrymandered minimums in assorted speed, power, and playing time categories. He also routinely performed feats that were without precedent—or, at least, unseen since the time of Tungsten Arm O’Doyle. I covered Ohtani’s unicorn year before it began and a few times toward its peak, but even a newborn baby daughter wasn’t going to stop me from saluting my large adult son one last time in this end-of-season summation. Before we bid goodbye to Ohtani until 2022, let’s highlight 10 stats that add wonder and depth to the story of a season that broke the baseball mold.

5.4: The difference between Ohtani’s actual vs. projected FanGraphs WAR totals

In one sense, it’s unsurprising that Ohtani put it all together in 2021: He’d already done it all in his age-21 season in Japan, for which he won the Pacific League’s MVP award. That was the season that made many American observers start salivating over what he might one day do in MLB. But between those two years, Ohtani suffered a string of significant injuries that resulted in surgeries on his ankle, elbow, and knee. He missed a ton of time, particularly as a two-way player, and when he was on the field, some of his skills were compromised. Over the winter, he sounded despondent about his poor performance last season, in which he was hobbled by a bum knee and elbow, hit poorly, and pitched only twice (badly both times) before being shut down on the mound. Even the early-spring stories about Ohtani’s offseason overhaul couldn’t quell the doubts about his durability or his future role.

A healthy Ohtani had plenty of potential to be a breakout player, but the odds that he’d stay healthy and play toward the top end of his expected range on a rate basis seemed slim. So slim, in fact, that FanGraphs’ preseason projections—a combination of the ZiPS and Steamer systems’ statistical verdicts and playing-time estimates from FanGraphs staffers—pegged him for only 2.7 WAR. Ohtani’s FanGraphs WAR is the lower of his two MLB-leading WAR totals, but even so, the gap of 5.4 wins between his projected and actual totals made him baseball’s biggest projection outperformer.

Biggest Outperformers in FanGraphs WAR, 2021

On the team level, this season held more than the usual number of serious surprises: For the first time since Baseball Prospectus’s PECOTA projections debuted in 2003, the system missed by 18 or more wins on a record five teams: the Diamondbacks (25 under), the Twins and Nationals (20 under), the Mariners (18 over), and the Giants (a record 33 over), not to mention the Mets at 16 under. On an individual level, though, there was no surprise as pleasant as Ohtani’s potential paying off. At times this season, Ohtani played so well that it seemed silly not to have seen his huge campaign coming. And yes, some concerns about his abilities were way overblown. But a season this great was never inevitable.

1.2: The difference in Baseball-Reference WAR between Ohtani and the runner-up

A difference of 1.2 WAR doesn’t sound like a lot, but at the top of the leaderboard in an ultra-competitive era, it’s unusually large. Over the past 35 seasons that weren’t severely curtailed—so, dating back to 1986 and excluding 1994 and 2020—the average gap between the no. 1 and no. 2 finishers in Baseball-Reference WAR was only 0.7 wins. In only five of those 35 years, and two of the past 20—1991 (Cal Ripken Jr.), 1997 (Roger Clemens), 2000 (Pedro Martínez), 2001 (Barry Bonds), and 2012 (Mike Trout)—was the WAR gap larger than 1.2. So despite a second-half drop-off in his power pace (which we’ll get to below), Ohtani still maintained a sizable separation between his 9.0 WAR and Wheeler’s at 7.8, and an even wider gulf between his WAR and leading AL rivals Carlos Correa, Semien, and Guerrero at 7.2, 7.1, and 6.8, respectively.

7.66 and 7.62: Ohtani’s win probability added (WPA) and run expectancy wins (REW)

I’m cheating a bit here: WPA and REW are separate stats, but they’re conceptually similar and, in this case, yield almost identical, major-league-leading figures. Ohtani is the 2021 WAR king, but WAR may underrate how valuable he was to the Angels, and not only because of the marginal, unmeasured value that he may add by (sort of) saving the team a roster spot. He was also incredibly clutch, or as clutch as a player whose team didn’t come close to making the playoffs can be.

WAR is context neutral, which means it doesn’t take into account the situation in which a player performs: To WAR, a homer is a homer, whether it’s a walk-off shot or an added insult in a blowout. WPA and REW are context sensitive, to varying degrees. WPA measures the change in win expectancy between the start and end of each play, which depends in part on the inning and score. (The later and closer the situation, the bigger the boosts or debits in WPA.) REW measures the change in run expectancy, so it considers the base-out situation but not the inning or score.

WPA-wise, Ohtani lapped both leagues.

FanGraphs WPA Leaders, 2021

FanGraphs’ WPA data dates back to 1974. In the seasons since then, the only player who’s led the second-place finisher by a wider margin than Ohtani did this season is Barry Bonds, who did it in 2001, 2002, and 2004. Ohtani’s lead in REW wasn’t nearly as large, but he still led the majors.

FanGraphs REW Leaders, 2021

The secret to Ohtani’s strong showings according to context-sensitive value stats was opportune timing. As a batter, Ohtani bumped his OPS from .876 with the bases empty to 1.091 with runners on and 1.165 with runners in scoring position. He easily led the majors in OPS in high-leverage situations (1.276), and he also ranked close to the top of the league in tOPS+ (167), which compares his OPS in high-leverage moments to his OPS overall. (By comparison, the 2021 Mariners, whose knack for raising their game at the plate in big moments nearly propelled them to the postseason, led all teams since 1901 with a 139 tOPS+ in high leverage.)

Ohtani’s splits on the mound were a mirror image of their offensive equivalents. As a pitcher, he allowed a .724 OPS with the bases empty, which he improved to .491 with runners on and .380 with runners in scoring position. His .376 OPS allowed in high-leverage situations was the third-best mark in the majors. (He also ranked second in high-leverage pitcher tOPS+.) Generally, surprise players and teams can be unexpectedly good (like the 2021 Giants) or unexpectedly lucky/clutch (like the 2021 Mariners). Ohtani’s 2021 combined the best of both worlds: He was good all the time, but great when it mattered most.

That clutchness could be persuasive to some MVP voters, not that Ohtani needs something to sweeten his case. The biggest threat to Ohtani is Guerrero, who led the AL in most major offensive categories. Along with his power and patience, Guerrero recorded a .311 batting average, which may look enticing to old-school eyes next to Ohtani’s .257. If Ohtani wins the award, he’ll lower the bar for batting average by a non-full-time-pitcher MVP, a distinction currently held by Marty Marion in the NL (.267 in 1944) and Roger Maris in the AL (.269 in 1961). Of course, Ohtani is a part-time pitcher, playing (and raking) during a low-average era in which most voters no longer look at batting average as an evaluative tool.

At least Ohtani isn’t going head-to-head with the star of a playoff team: Although the Jays finished with the fifth-highest run differential in MLB, they, like the Mariners, were eliminated on Sunday. If Fernando Tatis Jr., Juan Soto, Bryce Harper, or Wheeler wins the NL award, 2021 may mark the 11th time, and the first time since 1987 (George Bell and Andre Dawson), that both MVP awards went to non-postseason players. Historically, only 29.5 percent of MVPs have come from non-playoff teams, and as the playoff field has grown, that rate has fallen from 33 percent prior to 1969 to 26.2 percent after 1969, and to 19.2 percent since 1994.

1,172: Ohtani’s combined plate appearances and batters faced

Ohtani’s talent often comes across in a single swing, a single pitch, or a single standout game—one of the ones in which he homers while pitching a gem, or blasts a ball 110 miles per hour or more and also beats out a bunt hit. Yet he fared so well in counting stats such as WAR, WPA, and REW in large part because he simply played more baseball than anyone else, by virtue of his dual role and the lack of restrictions imposed on his usage. Fans who focus on how well Ohtani played tend to give short shrift to how much he played, but the latter is almost as mind-blowing.

Ohtani’s total of 1,172 combined plate appearances as a hitter and batters faced as a pitcher (not counting his two plate appearances and three batters faced in the All-Star Game) towered over the second-highest total in 2021, Zack Wheeler’s 922. You have to go back decades to find players who pitched deep enough into pitching appearances and accumulated enough plate appearances to approximate Ohtani’s tally, which was bolstered by Angels manager Joe Maddon’s decision to forgo the DH in 20 of Ohtani’s 23 starts as a pitcher. Ohtani topped Liván Hernández’s total of 1,162 in 2005 to claim the high score for this century. The most recent players to amass more than Ohtani’s total were Randy Johnson in 1999 (1,183), Curt Schilling in 1998 (1,180), and Orel Hershiser in 1988 (1,173). And Ohtani likely would have surpassed that trio too, making him the high man since Hershiser and Fernando Valenzuela in 1987, if Maddon hadn’t excused him from his scheduled start on the last day of the season.

Ohtani was almost always available to play at least one way. He played in some capacity in 158 games, and two of the four he watched from the sideline were interleague contests without a DH. (One of the others was the first game of a doubleheader.) He had starts as a pitcher postponed, but he didn’t sit out a single game because of injury. Consequently, he blew by his previous single-season highs in games played and plate appearances, and his innings count dwarfed his injury-suppressed total (79 2/3) from the previous four seasons combined. If his health holds up, he’ll be poised to take a run next season at his single-season high of 162 2/3 innings pitched, which he set for the Fighters in 2015.

In light of his recent track record, it seems almost miraculous that Ohtani stayed healthy while doing an inordinately demanding job in a season marred by fragile stars. As others have observed, 2021 is the first non-shortened season in MLB’s modern era (1901-present) not to feature a single 7-WAR position player. So many of the defining faces of baseball in 2021, who could have eclipsed that mark, missed most or part of the season: Mike Trout, Ronald Acuña Jr., Byron Buxton, Jacob deGrom, Tatis, and more. According to info from Baseball Prospectus, leaguewide injury rates spiked compared to pre-pandemic levels, perhaps partly a by-product of pandemic-era training disruptions and workload fluctuations.

Non-COVID IL Placements and Days Missed

Granted, Ohtani didn’t have to play the field, save for 8 1/3 combined innings in the outfield corners that he accumulated following some of his starts as a pitcher. (Sadly, Ohtani never started a game as an outfielder, and he never had an opportunity to catch a ball in left or right.) In other respects, however, his double-duty job subjected him to more physical strain than most players endure. As a base runner, Ohtani drew 77 pickoff throws, many of which forced him to dive back to a base; all players whose primary position was pitcher combined to draw only 18 total pickoff attempts. No other American League pitcher was hit by a pitch, but Ohtani was drilled four times. He bounced back from a number of scares that could have cut his season short, but didn’t: April blister problems; a disturbing velocity drop in mid-May; a painful foul off his right knee in mid-June (another non-hazard for most AL pitchers); an early-August thumb injury caused by a foul ball; a late-August fastball to the back of his pitching hand that required X-rays; a hard-hit comebacker off the hand in early September; a sore arm in mid-September.

Which play looks more like the cause of a season-ending injury? This …

… or this?

Clearly the latter, which looked like a recipe for another knee or ankle catastrophe. Yet Ohtani returned to action in the game after his April 4 collision with José Abreu, whereas Trout’s innocuous-looking calf strain on May 17 was so slow to heal that he spectated the rest of the season. Ohtani’s historic campaign could have been derailed a dozen times, but this year, fortune favored him.

1.5 mph: The difference between Ohtani’s fastball speed with RISP vs. bases empty

One explanation for Ohtani’s 2021 durability, professed lack of fatigue, and habit of being harder to hit in big moments is his affinity for holding some speed in reserve—or, as Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson referred to it, “pitching in a pinch.” Ohtani shows a pronounced tendency to throw harder as the game goes on, and to dial up his radar readings when he needs to. Ohtani throws his fastball a full ticker harder from the fifth through the seventh than he does in the first and second, and his bases-empty speed of 95.24 climbs to 96.75 with runners in scoring position. For instance, in a two-out, two-on jam against the Rangers on September 3, Ohtani threw a 100.4 mph fastball to get Jason Martin swinging, after averaging 95.5 prior to that inning.

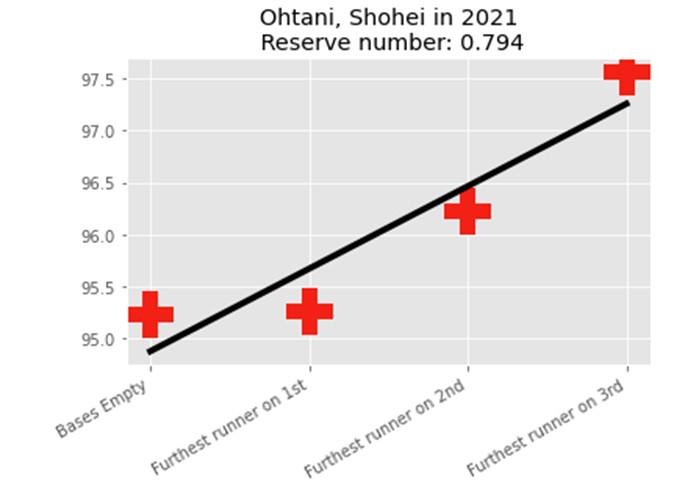

We can quantify this Ohtani trait—or, at least, Eric Fridén can. Fridén is a researcher who shared two new metrics that can assess Ohtani’s affinity for throwing harder in high-leverage spots and later in games: “staying power” and “reserve power.” Reserve power, Fridén says, presents the average increase in four-seamer speed for each base a runner advances, so that a pitcher who throws 90 mph with the bases empty, 91 with a runner on first, 92 with a runner on second, and 93 with a runner on third would have a reserve power of 1.0. At 0.794, Ohtani wasn’t far from that in 2021: He led all pitchers with 100-plus innings pitched and 100-plus four-seamers thrown, and dating back to the beginning of the pitch-tracking era, he trailed only famous speed conserver and innings eater Justin Verlander (in seven seasons) and Andrew Miller (in 2008).

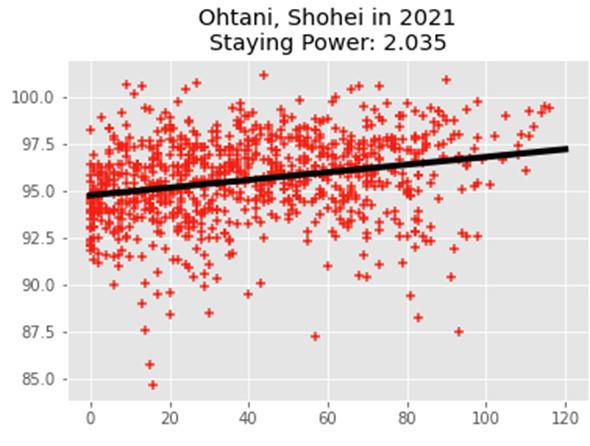

Staying power measures the average increase in four-seamer speed over 100 pitches. A staying power of 1.0 represents a pitcher who, on average, throws four-seamers 1.0 mph faster on pitch 100 than on pitch 1. Among pitchers with 100-plus innings pitched this season, Ohtani’s staying power of 2.04 trails only Carlos Rodón’s 3.42. Rodón (this year and in 2018), Verlander (in 2012), Bartolo Colon (in 2015 and 2013), and Johnny Cueto (in 2014) are the only qualifiers who’ve surpassed Ohtani’s 2021 staying power in a season.

In all, Fridén finds that Verlander himself and Rodón are the only pitchers who’ve exceeded Ohtani in “Verlanderiness,” a mashup of reserve power and staying power. Resembling Verlander sounds like a decent strategy. Most pitchers throw only a tad harder in big spots than they do in normal ones, and most pitchers lose speed as the game goes on. But a pitcher with Ohtani’s stuff and arsenal can survive and thrive without throwing max effort on every offering.

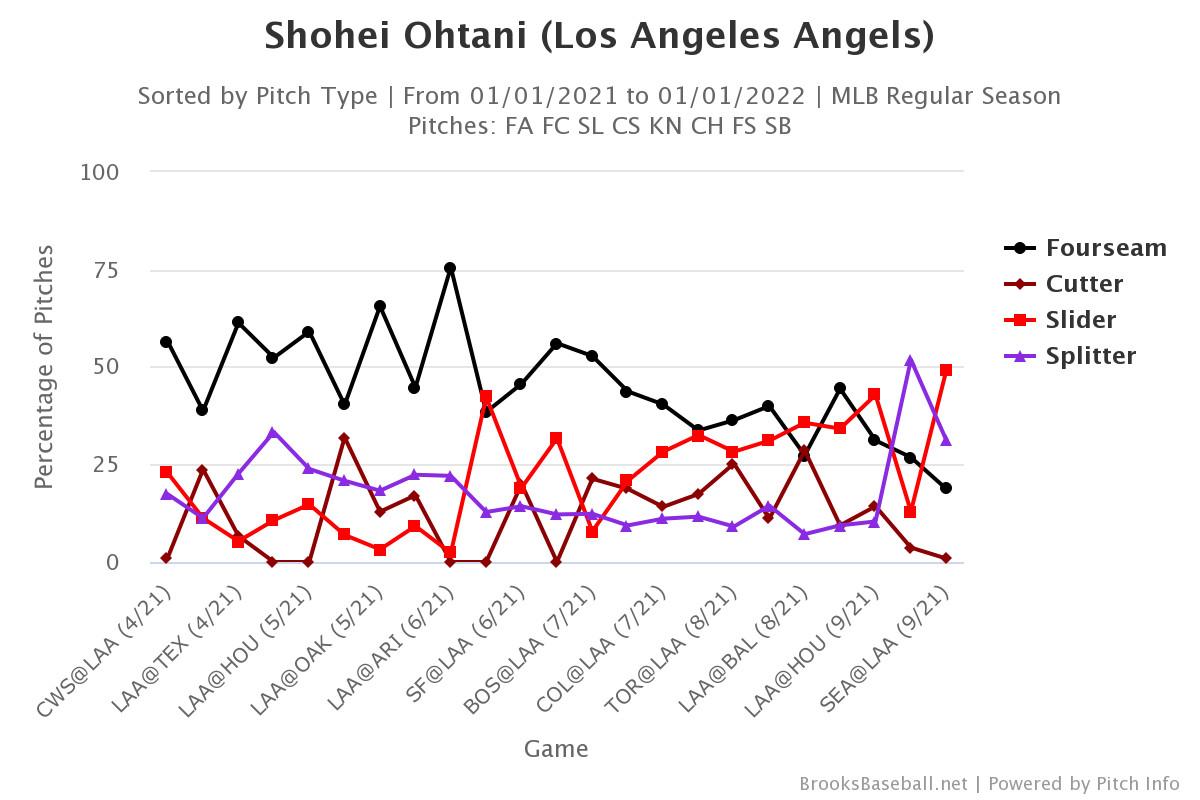

10.5: The standard deviation of Ohtani’s pitch-type usage from start to start

Ohtani’s tendency to tinker within pitching appearances also extends across them. He may be a creature of routine in how he approaches practice, but he has no script in games. Each start is a freestyle. Throughout the year, Ohtani dabbled in additions to (or variations on) his standard repertoire, working in a new, strike-seeking cutter, a harder, swing-and-miss curve, and a reoriented splitter, a tweak to a pitch that was already one of baseball’s best. And on any given two-way day, there was never any telling which of his four main pitches—four-seamer, slider, splitter, and cutter—he would depend on.

Ohtani’s four-seamer ranged from 76 percent of his pitches in one start in June to 19 percent of his pitches in one start in September. His cutter could be anywhere from almost a third of his offerings to entirely absent. His slider topped out at 49 percent usage and bottomed out at 2 percent usage. As for his splitter, he switched from throwing it 7 percent of the time in a late-August game to 52 percent of the time less than a month later.

Among the 30 pitchers this season who faced at least 500 batters and threw four pitch types (combining four-seamers and sinkers) at least 9.5 percent of the time, Ohtani’s standard deviation in start-to-start pitch-type usage was unmatched. In other words, the average variation in his usage of each pitch type from one start to the next was 10.5 percentage points. Maybe he’s still experimenting and discovering what works. As Max Scherzer said this summer, “It takes years to develop as an ace, and he’s in that development process. But his athleticism will allow him to reach his potential.” And as Ohtani echoed in August, “I’m getting better each outing, and I still haven’t hit my potential yet.”

5.8: The post-June ratio of Ohtani’s walk rate as a hitter to his walk rate as a pitcher

Through May, Ohtani walked 16.9 percent of the hitters he faced, the second-highest rate among pitchers with at least 30 innings pitched. When he was a hitter over that same span, he walked only 7.8 percent of the time, a slightly below-average rate. He was walking his opponents more than twice as frequently as he was walking against his opponents.

In June, that ratio roughly reversed itself: Ohtani started walking at roughly twice the rate that he was issuing walks. He also exploded on offense, slashing .309/.423/.889 and launching 13 homers. That month, Ohtani produced 2.35 FanGraphs WAR, about a tenth of a win short of deGrom and Gerrit Cole’s Aprils on the 2021 leaderboard for most valuable calendar months. (Take out or replace Ohtani’s disaster start on June 30, in which he recorded only two outs in a start at Yankee Stadium and was charged with seven earned runs, and he likely would have blown by both aces.) He won the AL Player of the Month Award, and he’d repeat in July as his walk differential really ramped up.

From July on, Ohtani walked only 2.6 percent of the hitters he faced, the lowest rate among the 114 pitchers who threw at least 55 innings over that span. Meanwhile, he was walking in 19 percent of his plate appearances, second only to the highly selective Soto. On the mound, he was leveraging the command that came with shaking off the post-surgical rust, throwing more pitches in the strike zone, and trusting his stuff. At the plate, opposing pitchers were mistrusting their stuff, because he was crushing it. They threw fewer pitches in the zone, and he chased balls less often. The player whose ratio of walk rate as a pitcher to walk rate as a hitter was way underwater early on had suddenly started walking almost six times more often than he was walking others. And he did that despite being slightly more likely than average to have strikes called against him at the plate, and despite throwing most of his pitches to Kurt Suzuki, one of MLB’s worst framers. (On the bright side, Statcast says he got good defensive support otherwise, even though the Angels weren’t a good defensive team.)

All would have been well in Ohtani town, except for our next stat.

.458: Ohtani’s second-half slugging percentage

If there’s any lingering letdown stemming from Ohtani’s superlative season—and if there is, it’s a sign that we’re spoiled—it’s that he didn’t finish stronger at the plate. Ohtani and Soto may both win MVP awards, but their offensive fortunes diverged dramatically right around when they dueled at the Home Run Derby.

Ohtani was still a useful hitter in the second half, posting a 121 wRC+, but that swoon (by his first-half standards) may have cost him a home run crown and the first 50-25 season. Maybe, as Angels hitting coach Jeremy Reed opined, the mental grind got him down, if physical fatigue didn’t. Maybe he put pressure on himself to power a depleted offense that was the worst in the game after the trade deadline. At times, he saw fewer strikes and swung at more balls, a product of lineup “protection” that consisted largely of Phil Gosselin and David Fletcher. In late September, he walked 11 times in three games and 13 times in four games, tying two AL/NL records. Like Soto, he led his league in intentional walks.

In the first half, Ohtani pulled 43.1 percent of his batted balls. In the second half, he pulled 54.8 percent of them. Among the 142 hitters who made at least 200 plate appearances in both the first and second halves, that increase in pull percentage ranked third. Ohtani hit five oppo homers in 2021, but none after July 2. He hit 15 homers straightaway, but none after August 11. His last eight dingers were all yanked to right field. Teams took notice of his increasingly pull-heavy stroke: From April through June, Ohtani was shifted on 52 percent of pitches, which put him in the 53rd percentile among left-handed hitters who saw at least 500 pitches. From July 1 on, he was shifted on 88 percent of pitches, which elevated him to the 92nd percentile. (Surprisingly, his BABIP on grounders went up.)

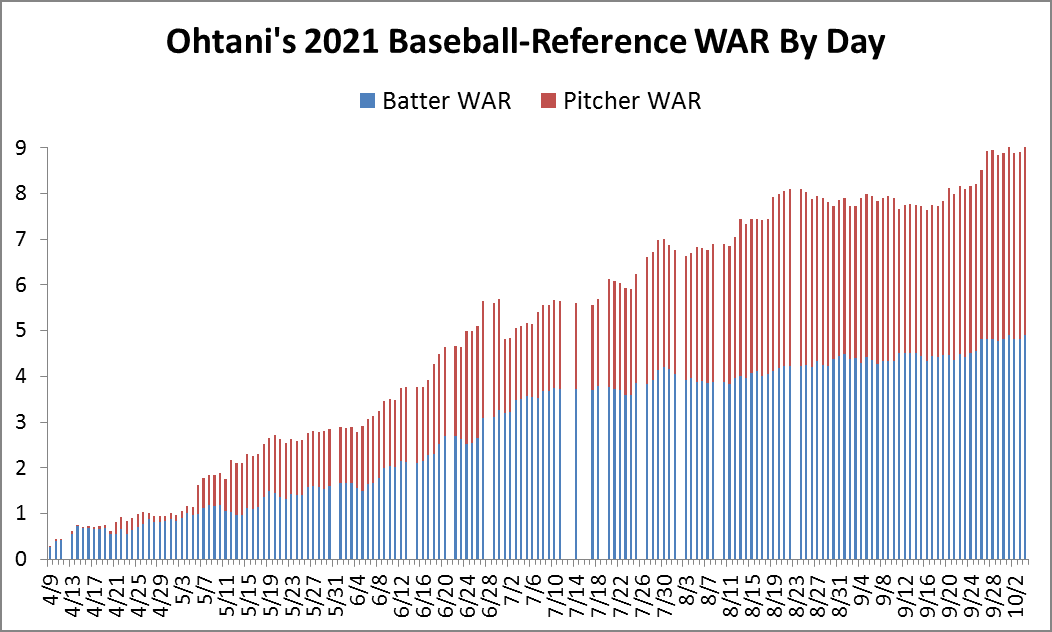

The upshot of all of this is apparent in a graph of Ohtani’s batter and pitcher WAR from Baseball-Reference’s daily WAR archive (which isn’t quite daily). As the season proceeded, Ohtani’s batter (and combined) WAR gains slowed, but his pitcher WAR picked up some of the slack and became a bigger part of the production picture.

4.09: Ohtani’s average home-to-first time

Compared to his triple-digit pitch speeds and glove-destroying batted balls, Ohtani’s foot speed is an afterthought, but the batter who trailed only Giancarlo Stanton in average home run hardness was also among the league leaders in bunt hits and infield-hit rate. On top of everything else he accomplished this year, Ohtani boasted baseball’s fastest average home-to-first time among the 237 players with 100 or more “competitive runs.” That’s two parts 91st-percentile sprint speed and one part pure hustle, the latter of which makes it even more remarkable that he didn’t pull a muscle busting it down the line in the year of rampant hamstring strains.

Judging by the way opposing pitchers treat Ohtani when he reaches base, even the overawed athletes who see him up close may view him as more of a slugger or pitcher than the base-stealing threat he is. In general, the more often a runner takes off, the more often he draws pickoff throws. Among players with at least 200 stolen-base opportunities in 2021—defined as situations where a runner was on first or second with a base open ahead of him, and the ball wasn’t put in play—the correlation between stolen-base attempts per stolen-base opportunity and pickoff attempts per stolen-base opportunity was a robust .77.

For Ohtani, though, this relationship isn’t as strong: In 2021, he drew the same number of pickoff throws as less prolific swipers such as Dylan Carlson, Alex Verdugo, Elvis Andrus, and Kevin Kiermaier. On average, pitchers made 9.8 pickoff attempts per 100 pickoff opportunities. The rate against Ohtani was only slightly elevated—13.3 percent—which ranked 95th out of 322 qualifying runners. Yet he ranked 11th in stolen-base attempts per stolen-base opportunity, which suggests that pitchers should have made him hit the dirt more often. Maybe they were taking pity on a fellow pitcher; maybe they were distracted by his other skills. But when Ohtani smells a hit, he’s as adept as anyone at getting down the line. And when he gets on, he’s often going to go.

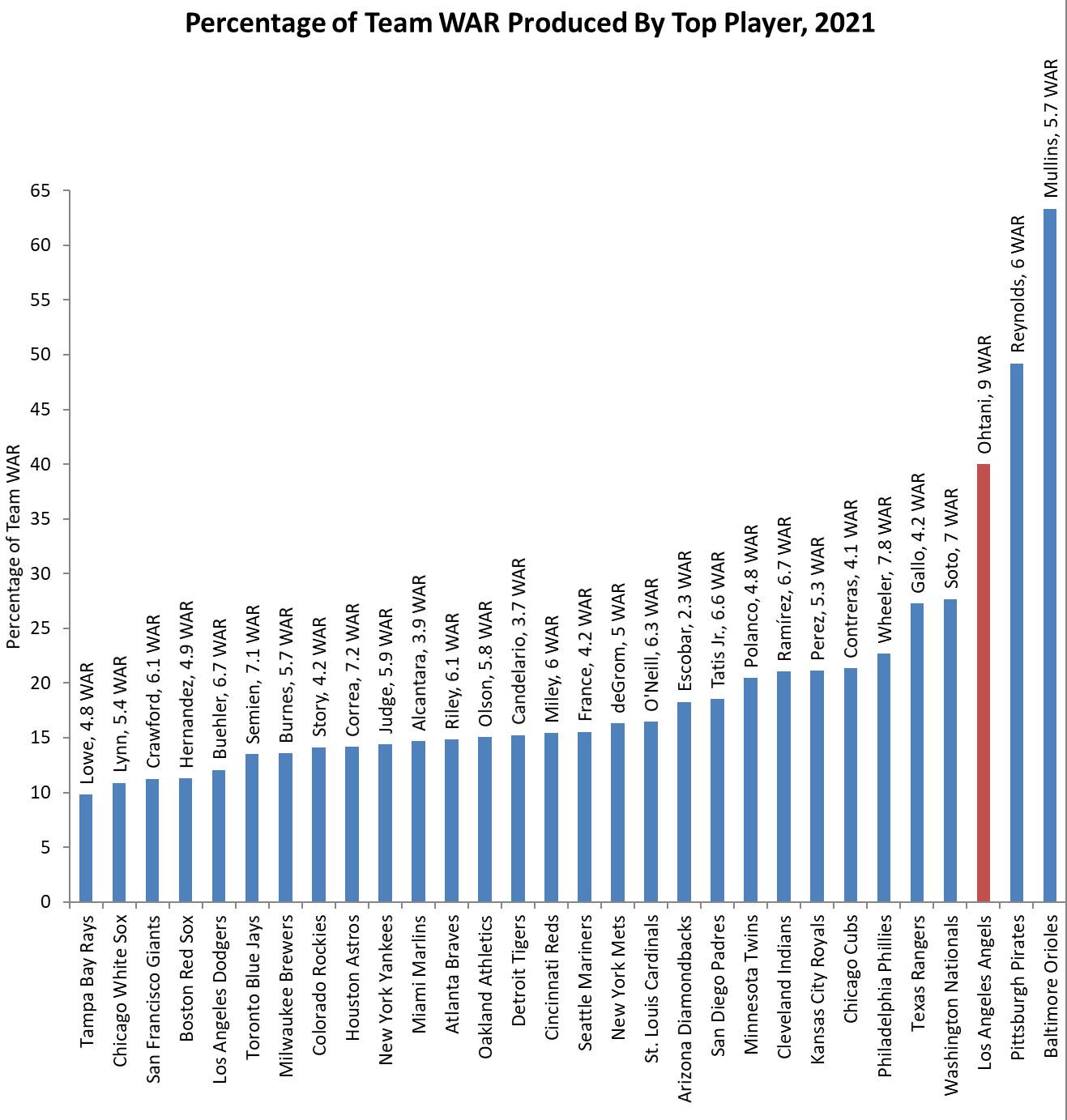

40.0: The percentage of 2021 Angels WAR produced by Ohtani

With Trout and Anthony Rendon on the shelf for most of the season, the Angels’ roster was reduced to star and scrubs. Ohtani’s 9.0 Baseball-Reference WAR represented 40 percent of the team’s total. Among the leading WAR-getters on every other team, only Bryan Reynolds and Cedric Mullins II, the prides of the lowly Pirates and Orioles, respectively, accounted for higher proportions of their respective teams’ totals. Ohtani, who led the Angels in … well, everything, was named the team’s MVP and pitcher of the year, a possible prelude to higher-profile award wins next month.

As usual, the Angels had hard luck this year: Ohtani outperformed his preseason projection more than anyone else, but Trout and Rendon underperformed their projections more than any other player except the Dodgers’ Cody Bellinger. Credit the Angels with the 10.1 WAR FanGraphs projected them to get from Trout and Rendon instead of the 3.0 WAR they did get, and the team might have made things more interesting. But pitching remained a problem, as did depth.

I’ll leave you with one bonus stat as we anticipate the sequel to Ohtani’s 2021. It’s .500: the Angels’ preliminary projected winning percentage in 2022, per ZiPS.

Preliminary ZiPS-Projected 2022 AL West Standings

These projections consider only the players under team control today, but as of now, the Angels seem positioned to repeat their pattern of quasi-contending before fading away. There’s hope here, though, delivered both by the Trout-Ohtani-Rendon trifecta, complementary contributors such as Patrick Sandoval and Jared Walsh, and promising youngsters Reid Detmers, Jo Adell, Brandon Marsh, and Chris Rodriguez, plus the future fruits of the Angels’ all-pitcher draft (especially if living conditions in the Angels’ system improve).

In addition to hope, there’s pressure: In recent days, Maddon, Trout, and even Ohtani have voiced frustrations about the team’s stagnation in the standings, and urged ownership to spend the money that’s about to be freed up. Seattle is ascendant, and although the Mariners may suffer some regression next season, the Angels’ window with their core could be closing. In the waning days of the season, Ohtani made comments that some saw as a warning that he’ll walk when he reaches free agency after 2023, although others disputed that interpretation and Ohtani subsequently signaled his willingness to discuss an extension.

Despite the rest of the roster’s efforts to make Angels games uninteresting, Ohtani made me tune in to otherwise lackluster, low-stakes games night after night, wherever I was and whatever I was interrupting. (Last week, my wife and I watched an Ohtani at-bat in the delivery room.) I followed his season, pitch by pitch and box score by box score, in a way that I haven’t had the desire to do since I was 11 and obsessed with Sosa and McGwire. There’s no shortage of riveting talents in MLB, but none of them is quite as compelling as Ohtani when he’s demonstrating mastery over every facet of the sport. Unless and until another blessed-by-the-baseball-gods ace-slugger-speedster surfaces, the only spectacle that could top Ohtani’s last season is, perhaps, his next one—and someday, somewhere, a two-way appearance on the postseason stage.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris, Rob Mains, and Derek Rhoads of Baseball Prospectus, Dan Hirsch and Kenny Jackelen of Baseball-Reference, Dan Szymborski of FanGraphs, Jessie Barbour, and Eric Fridén for research assistance.