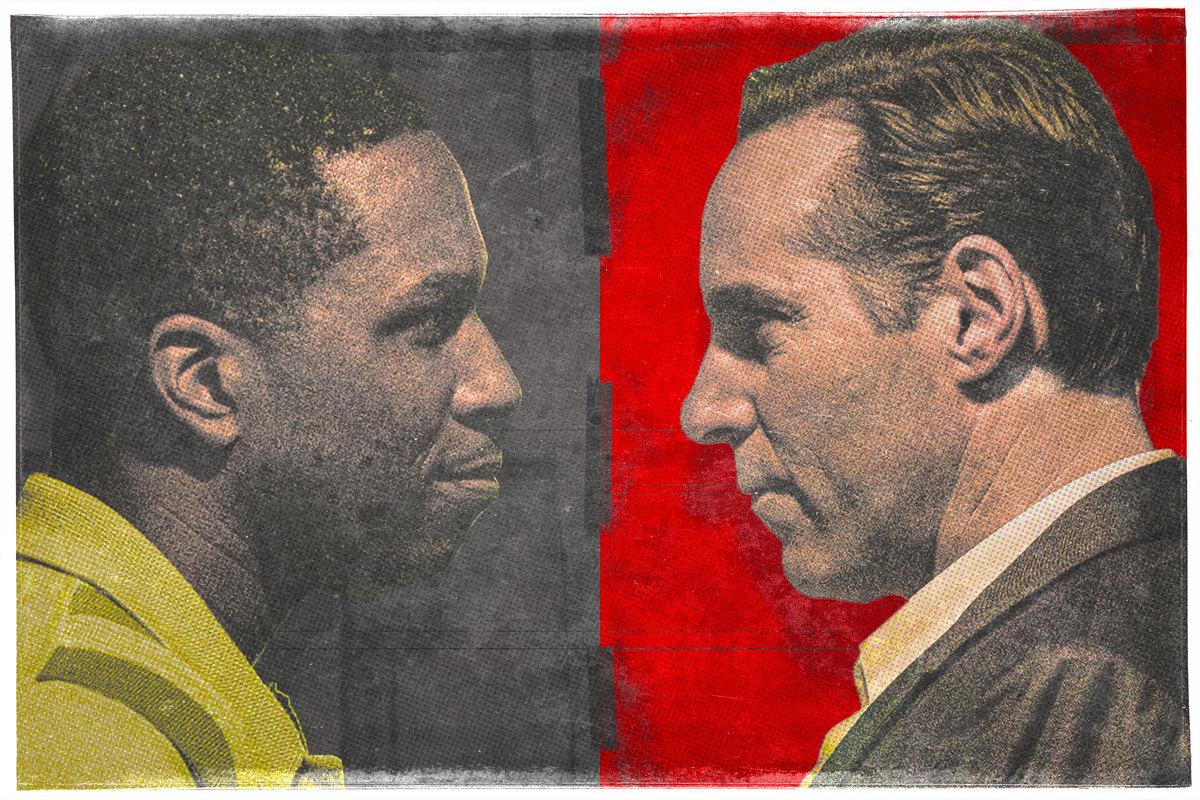

Not knowing your place in the world of organized crime is often a fatal mistake, but in The Many Saints of Newark, Harold McBrayer’s problem is that he knows his all too well. As a numbers runner for DiMeo crime family soldier Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola), Harold (Leslie Odom Jr.) realizes that he’ll always be beneath the thumb of the former classmate who barely conceals his racism and seizes every opportunity to remind him that they aren’t equals. Harold’s aspirations are at odds with the racial dynamics of the underworld, which, fittingly, resemble the rest of society. His simmering resentment soon bubbles over. First and foremost, he’s fed up with being Dickie’s errand boy; there’s no path to advancement there. Then he witnesses law enforcement’s lethal response to the looting triggered by the Newark police’s arrest and beating of cab driver John William Smith, a Black man, in July 1967. Soon after, he’s right in the middle of the uprising, hurling a Molotov cocktail at a police car. Within Sopranos mythology, the 1967 Newark riots are supposed to be a turning point in the life of a young Tony Soprano and his family, but The Many Saints of Newark shows that they’re also the proxy for Harold’s rebellion.

The Sopranos succeeded at stripping the Mafia lifestyle, as depicted by pop culture, of whatever glamour remained by the end of the 20th century. It zoomed in on its characters’ flaws while holding a mirror up to its audience: Mobsters, they’re just like us, the show argued in blunt fashion. The Sopranos was frank in its depiction of racism, capturing the contempt this group of hypocrites—like a significant portion of the United States—held for anyone who wasn’t white. It was canonical: Think Don Zaluchi having no issues selling drugs in Black communities because “those people are animals” in The Godfather, Henry Hill saying only “nigger stickup men” go to jail “because they fall asleep in the getaway car” in Goodfellas, or Tommy DeVito’s girlfriend tiptoeing around expressing her attraction to Sammy Davis Jr. for the sake of Tommy’s ego in the same film. The Sopranos showed how the racism evolved, but the general attitudes remained the same. But despite how accurate the portrayals were, the lines between standard racist mobster perspectives and white writers’ oversights were blurred. Take, for example, Bokeem Woodbine as Massive Genius, an amalgam of absurd rapper stereotypes—even by late 1990s standards. Alas, depth of character is a stretch when the characters are viewed through the eyes of people who don’t see them as human and created by people prone to oversight. This never ruined The Sopranos, but it always stood out. Fourteen years after The Sopranos concluded with one last dig at the audience, creator David Chase, cowriter Lawrence Konner, and veteran Sopranos director Alan Taylor appear eager to make amends through Harold and The Many Saints of Newark. And while the intent is admirable on some levels, the result is scattershot.

Concerted effort aside, the primary reason The Many Saints of Newark does a slightly better job of handling non-white characters than The Sopranos (granted, the bar is scraping the floor) is Odom’s performance. He perfectly captures the ambition and frustration that push Harold over the edge and into war with Dickie. You can see the resentment stewing within him as Queen Isola (Patina Miller) explains his job to her son early in the film. “Harold collects everybody’s bets and gives it to the Man,” she says. “How you think the Italians drive those long, fancy cars and wear those diamond Swiss watches on their wrists?” The resentment grows even deeper when Harold is forced to flee to North Carolina to duck a murder charge. After giving Harold half the money he asked to borrow, Dickie abruptly dismisses his former high school teammate despite all the work he’s put in on his behalf. It’s another cold reminder of his standing, and Odom is able to say as much without saying anything at all. The character, like The Many Saints of Newark itself, presents an opportunity to explore racism in a way the show didn’t throughout its 86 episodes. But despite wanting to speak up and trying in earnest to do so, The Many Saints of Newark can’t find the words.

The Sopranos offered a cynical snapshot of turn-of-the-millennium whiteness. Its deep dive into the Mafia lifestyle shone the spotlight on its characters’ chronic entitlement, victimhood, and incapacity for accountability. They murder, cheat, and steal with impunity in pursuit of a dying American Dream founded by way of the same tactics. Even Meadow Soprano, Tony and Carmela’s high-achieving daughter, was a white liberal joke: routinely claiming the moral high ground and testing the limits of her parents’ conservatism without ever rejecting the comfort they provided her. At the end of the day, the characters all crave the safety of their cul de sacs. These supposed renegades are in step with the majority of society—they just want someone to look down upon and use whatever discrimination Italian Americans experienced to justify their racism. Needing someone to feel superior to is very white (it’s damn near the American way), and both The Sopranos and The Many Saints of Newark emphasize this through their handling of the tension between Black people and Italian Americans. Despite their brutality and occasional flat-out stupidity, the mobsters and their families turn their noses up at Black people, who they view as savages.

In the film, Junior Soprano (a fantastic Corey Stoll) expresses disgust at Harold beating a Black gang member to collect money for Dickie, even though that’s what he’s employed to do. “You believe this?” he asks, aghast. “How these people prey on their own?” Never mind the fact that he and his cohorts do the same to their people—and that he’d later order hits on his own family members. It’s a special brand of cognitive dissonance that enables racists to enjoy the privilege of ignorance, indifference, or both. As Johnny Boy Soprano (an underused Jon Bernthal) is being led into a police van, he implores his arresting officers to “go after the ditsoon” burning the city down. When he returns home from prison in the early 1970s, he’s appalled to learn that a Black family has moved into his neighborhood and doesn’t care that the father is a doctor—even the “good ones” are unwelcome. And when Dickie learns that Giuseppina, his former stepmother turned mistress, slept with Harold out of spite, he drowns her after nearly losing his equilibrium in a scene reminiscent of Tony fainting shortly after meeting Meadow’s half-Black, half-Jewish boyfriend.

Tony believes Black people and Italians can coexist—as long as they remain separate, for the most part. The Sopranos provided an intimate look at the racism that takes place behind closed doors and the sense of superiority expressed through glances and offhand comments. White people will do business with Black people and even enjoy their art (in the film, Sally Moltisanti, played by Ray Liotta, is a Miles Davis fan; Giuseppina loves Dionne Warwick; Paulie, a chest-out racist, watches the Delfonics perform on Soul Train while curling a free weight), but Black men dating “their” women and daughters? Out of the question. They’re explicit about where they think Black people belong—beneath them—and the ways they appear in their lives underlines their racism. Black people are often scapegoats in this world: an easy source of blame because of how they’re viewed beyond it. In The Sopranos, the doomed Jackie Aprile Jr.’s death is blamed on “Black drug dealers,” even though he met his demise at the hands of the very crime syndicate his father was part of. In The Many Saints of Newark, Dickie kills his own father, Hollywood Dick (also played by Liotta), and blames his death on the riots. During the riots, Paulie (Billy Magnussen) and Pussy (Samson Moeakiola) steal a TV because they know the looting will be attributed to “the Harlem Globetrotters,” as Pussy crassly puts it. Junior orders the hit on Dickie while he’s at war with Harold; take a wild guess at who’ll be blamed for his murder. In this world, Black people are failed or would-be robbers dispatched when they’re no longer of use. They’re babysitters, plot devices, and borderline parodies. They’re instruments and casualties of racism, rarely given more than one dimension.

The key difference between Harold and the overwhelming majority of the Black characters who have passed through the Sopranos universe is that Chase and Konner aimed to establish his interior life. But the few glimpses The Many Saints of Newark offers all revolve around his anger at being subdued. When reflecting on storming into a recruitment center and murdering a gang member who owed him money, he’s more wistful about his felonies preventing him from joining the Army than even slightly conflicted about killing a Black teenager on the behalf of the man who, as Isola puts it, has made him “his house nigga.” After he returns from North Carolina in the early 1970s, his radicalization inspires him to establish a Black numbers bank funded by Frank Lucas (Oberon K.A. Adjepong). His “radical” solution is to paint capitalism Black. Harold’s entire arc is a quest for equality, but there’s nothing revolutionary about wanting to be equal to the white men who have held you back. Even after he sleeps with Giuseppina during his quest for revenge, he compares himself to Dickie in a moment of postcoital dirty mackin’. Everything about Harold revolves around “Goddamn Gentleman Dickie Moltisanti.” The attempt at creating a three-dimensional Black character merely produced a red herring who exists primarily to give Dickie a nemesis.

The Many Saints of Newark is not a bad film (it was always doomed to live in the Tony Soprano–sized shadow of the series), but it’s uncertain about what it ultimately wants to say. It has nothing sharp to offer regarding race or racism because it has no insightful ideas or arguments, in general. In place of Harold McBrayer’s politics or inner thoughts beyond Dickie Moltisanti, the audience is left with unfulfilled military dreams, an Afro, and on-the-nose Gil Scott-Heron song selections. The Many Saints of Newark clearly wants to atone for The Sopranos’ missteps, but isn’t sure how to accomplish that. Acknowledging a problem after the fact, trying to correct it, but not truly understanding how, is a perfect description of this supposed “moment of reckoning” in America. Even in the most well-intentioned instances, it’s a misguided effort: Wanting to take action without knowing what to do or say.

Julian Kimble has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Undefeated, GQ, Billboard, Pitchfork, The Fader, SB Nation, and many more.