Too Big to Fail

Rudy Gobert has become one of the most dominant defenders in recent history, but opponents have been able to knock the Jazz out of the playoffs by using small ball to neutralize the 7-footer. Can the old-school center stand his ground in the modern NBA? The game’s best shot-blocker has dealt with rejection plenty of times before.In Saint-Quentin, the blue-collar town in France where Rudy Gobert grew up, a festival is held every summer in which the town center is covered in sand, turning the Basilica-lined street into a beach vacation. There’s volleyball, a pool, food and drinks for the adults, and games for kids. One summer, there was trivia for a chance to win a Nintendo Wii. Before leaving to enter the contest, a 15-year-old Rudy called his shot and told his mom, Corinne Gobert, that he was coming home with a new console.

Gobert answered several of the questions correctly, including one about The Legend of Zelda to get to the final round. “Zelda was my shit,” Gobert says over the phone. But he was stumped by the last question, about a horror game that he had played before. He didn’t know the answer. Neither did his opponents. Then Gobert overheard a person watching from the crowd say the correct response: Resident Evil.

“I heard someone say it, and the other kids didn’t hear or react so I just said it right away. And it was the right answer,” Gobert says with a laugh. “It was probably the best day of my life at the time because I wanted it so bad, and I got it.”

Gobert clenched his Nintendo underneath his long arms so no one could easily steal it and run away with his prize. Soon, he found his mom and his older sister Vanessa. “We were having a drink and he came running with it in his hands,” Corinne recalls, through a French translator. “If Rudy wants something, he does anything to get it.”

La caboche. That’s what Corinne says Rudy inherited from her. She means he’s stubborn. He’s dogged. She says she was the same way growing up, and it’s the mindset she needed when she raised him as a single mother. Corinne had various jobs, from helping at restaurants to starting her own spa service, building a clientele of friends and regulars. Money was tight, though. She needed to make trips to Restos du Cœur, a French charity that gives food and goods to those in need.

Gobert saw how hard his mother worked raising him and his two older half-siblings, Vanessa and Romain. He wanted to be like her, putting his all into everything he cared about, whether it was video games, boxing, karate, basketball, or school. “He got his science baccalaureate at the first try,” says Corinne of the French diploma given to students at the completion of secondary school.

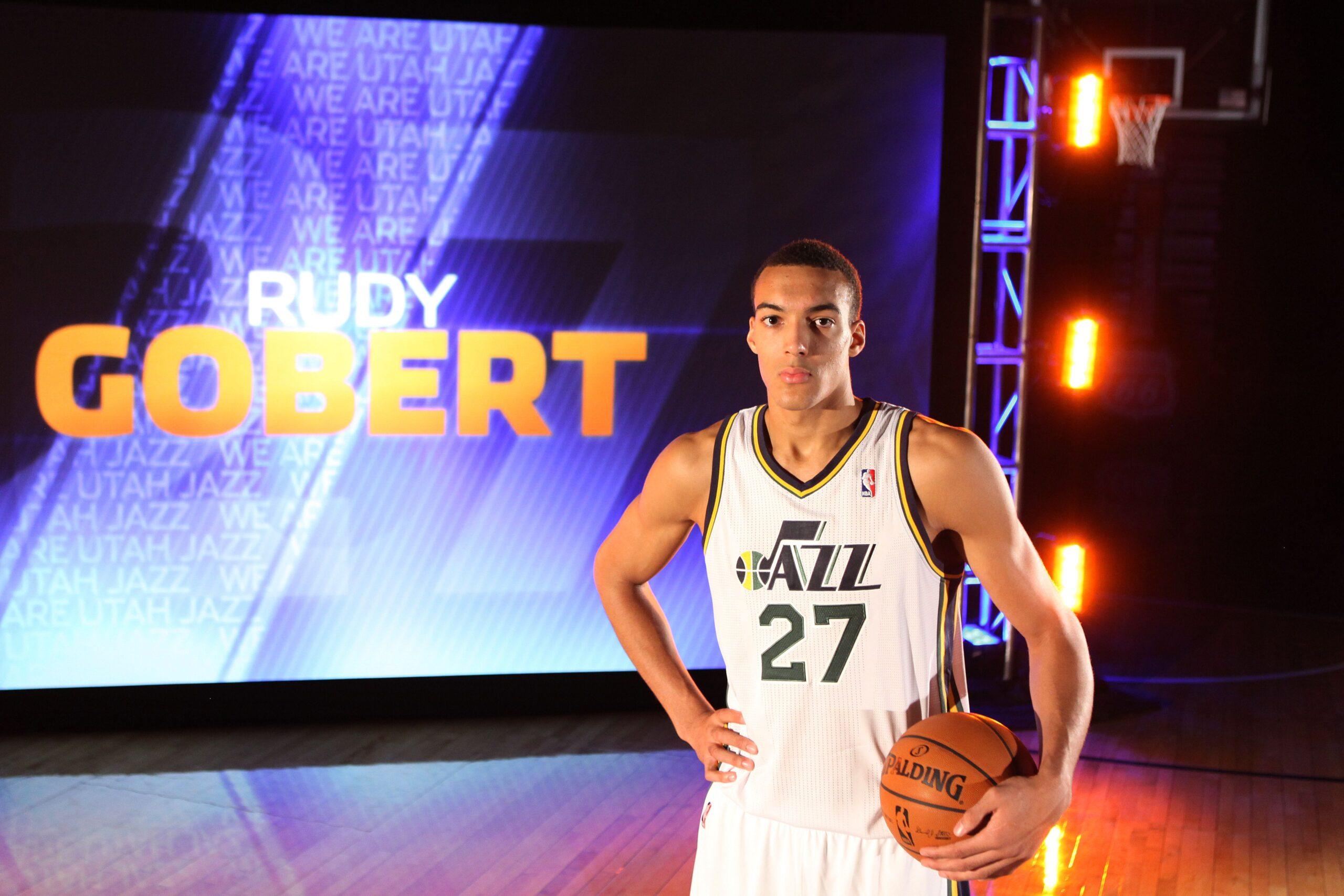

That determination is the bedrock of his NBA success. Selected 27th overall in 2013, Gobert has gone on to become a three-time Defensive Player of the Year and a four-time All-NBA player for the Utah Jazz. Now 29 years old, he’s in the first year of a five-year, $205 million contract—a sum greater than all but two contracts in the league. And with Gobert patrolling the middle, the Jazz have become one of the league’s most consistently successful franchises, winning 63 percent of their regular-season games over the past half-decade.

But that success hasn’t carried over into the postseason. Utah has failed to advance past the second round in five consecutive playoff appearances, losing twice in the first round. Last postseason, the Jazz took a 2-0 lead on the Clippers, only to lose four straight, with Kawhi Leonard sidelined for the last two. Fair or not, a lot of the blame for the playoff losses has been foisted onto the same player who has made Utah such a dominant force in the regular season.

Gobert is 7-foot-1and has an enormous 7-foot-9 wingspan. He’s huge, though unlike other giants who have come and gone in the NBA, he also has instantaneous reaction time. On defense, he’s a deterrent who lurks around the basket to prevent players from getting inside for layups and dunks. If a player breaches through, he’s an eraser who swats away shots with ease using his length. Over the past four regular seasons, the Jazz allowed only 0.8 points per pick-and-roll defended by Gobert, best in the NBA, according to Second Spectrum. That number is backed by opposing coaches, who consider him the best pick-and-roll defender in the league. He ranks highly in virtually every statistical category on defense, too. But his effect on the game has been diminished in the playoffs, since teams regularly downsize to put as much skill on the court. Opposing offenses space the floor with five shooters, all with the intent of pulling Gobert away from the interior and toward the 3-point line. So when players dribble by his teammates, he can’t be in a position to stop them like he normally would be. And if he lets his mark shoot freely in order to station himself near the hoop, you can wind up in a situation like in Game 6 against the Clippers, when Terance Mann suddenly became prime Ray Allen and knocked Utah out of the playoffs.

“We have the Defensive Player of the Year in Rudy. We’ve been able to defend in those situations this year,” Jazz head coach Quin Snyder said after the Game 6 loss. “It was a tough night in many respects on the defensive end, but I certainly wouldn’t jump to any type of conclusion.”

Since I’ve been a kid I’ve always hated to lose in whatever I do. It’s almost, I wouldn’t say too much, but it’s who I am.Rudy Gobert

The image of Steph Curry crossing the ball over and making Gobert spin around twice like he was playing Dance Dance Revolution back in 2017 remains a lasting image for many NBA fans, but he’s actually become effective for a center at containing players on the perimeter. When he’s forced to roam on the perimeter, he just can’t cover all five opponents at once. Utah had a lack of depth and size at the wing position last season, leading to constant penetration by one of the five ball handlers Los Angeles had on the court. The Clippers shot 46.1 percent from 3 after the Jazz went up 2-0; not even the doll from Squid Game could have eliminated them.

Gobert’s bigger issue is his inability to punish opponents on the other end for guarding him with smaller players. During the season, he makes an impact on offense by screening, rolling, or finishing. But he rarely creates his own shot, and in the playoffs, defenses would use schemes that don’t give him an open lane to run or roll toward the basket. Defenders wouldn’t need to help, thus neutralizing his best ability.

Perimeter players ultimately have the responsibility to circle the wagons and make a play in today’s perimeter-oriented game. That’s what the playoffs are. But Gobert has come to represent the growing chasm between regular-season and postseason basketball. He can nearly single-handedly make a defense great, and thereby turn a team into a winner; but as dominant as he is in the regular season, he hasn’t been able to ascend to a higher level in the postseason.

But Gobert is no stranger to adversity, even as he’s emerged as one of the game’s best centers. After being snubbed from the 2019 All-Star Game, he cried out of frustration in the midst of a media scrum. Last year, he was criticized for flippantly touching reporters’ microphones at the cusp of coronavirus pandemic, only to test positive soon after. And now, some question whether he can help lead the Jazz to the title if he can’t keep pace with the modern NBA.

“Just because I’m 7 foot, and I do what I do on the court, people tend to think that I’m just a robot,” he says. “But we’re all human beings. We all have emotions. Sometimes you let them out.”

But as he has throughout his life, Gobert embraces the challenge he has in front of him—one that will likely decide the fate of Utah’s season, and, maybe, the title race.

“Since I’ve been a kid I’ve always hated to lose in whatever I do. It’s almost, I wouldn’t say too much, but it’s who I am,” Gobert says. “I just embrace it. … I know I haven’t even scratched the Rudy that I can be, on and off the court.”

Gobert is always late. Last to stroll onto the team bus after games. Last to team meetings. Last to breakfast. “And sometimes he would also wear the wrong T-shirt,” says Boris Diaw, who was a teammate in Utah for one season and played with Gobert on the French national team. So in 2014, after Gobert’s rookie season with the Jazz, his French teammates decided to play a prank on him.

Players for France were required to wear the same exact outfits to team activities in Spain for the FIBA World Cup. “You’d have the blue, the white, and the red T-shirts,” Diaw recalls. “Since we always knew he was late, we knew he was gonna arrive last. So he was told it’d be one shirt, but we’d all wear another.”

Gobert walked in wearing the blue T-shirt that said “France Basketball” on it in white lettering. All of his teammates were wearing a dark blue polo shirt with a buttoned-up collar. Rudy was puzzled and sent back to change.

As soon as he was out of sight, his teammates all took off the polo. Underneath was the same blue T-shirt Gobert had gone back to his room to remove. Gobert knew he was duped again as he sat down at the table with his food. “You were all in polo shirts,” he said.

Gobert was sent back again, and they all put the polos back on. This time, he didn’t change shirts. “He just brought the other shirt back so we wouldn’t fool him,” Diaw says. “He was smart where it was like, if you fool me once, you won’t fool me twice.”

“In that case, it’s more you can fool me twice, but not three times,” jokes Knicks guard Evan Fournier, another French national team player, who has played against Gobert since they were 13.

That Gobert even made the national team is a surprise to those who saw him play when he was a kid. He was skinny. He wore glasses. He had a messy Afro. Gobert looked more like a gamer than an athlete.

“Well, Rudy, he’s a late bloomer. He was a shooting guard and he wasn’t very good. He wasn’t very skilled,” Fournier says. “Physically, he just wasn’t ready to play at all. He was still growing. He had no muscle. He was just a baby.”

Fournier, who was already a top French player for his age group, says few people really believed in Gobert, but he competed hard. “One of the reasons why me and him are very close is because I never gave him shit,” Fournier says. But plenty of kids did. Gobert would get laughed at by his peers when he’d tell them that he’d make it to the NBA. “Everybody was looking at me crazy,” Gobert says. “I wasn’t even the best player on my team back then.”

But basketball was in his blood. Gobert’s dad, Rudy Bourgarel, is a 7-footer who once hoped to make the NBA. He played college ball at Marist College in New York, and after returning to France to serve in the military had a short pro career overseas. Bourgarel returned to his home of Guadeloupe, a French-held archipelago across the Atlantic in the Caribbean, separating Rudy from his father for most of his childhood. But Corinne made sure her son kept in touch with him on the phone. They’d talk about his life in France, school, and, of course, basketball, once Gobert started playing at age 12.

Though Gobert wasn’t all that good yet, coaches and scouts around Saint-Quentin were aware of him because of his father’s career. Gobert was soon being recruited to play at a local academy called Pôle Espoir Régional de Picardie, in a town named Amiens, which is a one-hour drive from Saint-Quentin. Julien Egloff, a coach at the academy at the time, remembers the first time he saw Gobert play at a camp. Well, not play, exactly.

“Rudy was fighting on the court with another player. They were boxing,” Egloff says with a laugh. “This story is in my mind because of course you shouldn’t fight on the court, but he had some character. It’s a spirit that he had when he was younger when he was actually playing. If he fell on the floor, he would get up every time. He was a fighter.”

When Gobert was 14, Jean-Francois Martin, a coach from the French League team Cholet, began to scout him. Martin saw a kid with length who hustled, and thought he could become a contributor if he kept getting taller like his dad. When Gobert turned 15, he grew to 6-foot-3. Cholet wanted him to play for their junior team, but it was a five-hour drive or a 15-hour train ride away from Saint-Quentin. If Gobert went, he could return home only every couple of months, instead of every weekend like he did at the academy. Rudy and Corinne made the decision that he should go.

“She could have been like, ‘I don’t want you to go away from home. I want you to stay with me,’” Gobert says. “It was hard for her. But she allowed me to chase my dream.”

The first time I saw him, he was just a different dude. He was a lot taller. He had a different voice. It was crazy. Like in one year he just completely changed.Evan Fournier

Being away from home was a challenge at first. Martin says Gobert always practiced and played hard, but he was often late, tired, or both. Before the growth spurt that made him a center, Gobert was trained as a perimeter player, shooting 3s and handling the ball. “He was not able to finish near the rim,” Martin says. “His body was his weakness.”

Gobert says any benefit from lifting weights wasn’t recognizable. His body wouldn’t fill out, it would just stretch. But as frustrating as it was, he believes this experience helped sharpen his work ethic. “Nothing was evolving,” Gobert says. “But I got in the habit of always trying to get stronger every day, every year. And it stuck with me.”

Results weren’t apparent on the court at first, either. Over Gobert’s first three years with Cholet, he sniffed the court for the senior team roster only once. Gobert didn’t have the strength to drive to the rim or contain attackers, but he’d fight for a rebound or dive for a loose ball. He didn’t make many of his 3s or get many minutes, but he’d make the right pass or cheer for his teammates. Still, he played with the junior team and wasn’t on the radar for France’s under-16 national team.

Gobert would always say “just give me some time,” Martin says. Time to get stronger. Time to get better. Time to get taller.

During his second year with Cholet, Gobert grew to 6-foot-6 and he signed with the same agents he has to this day, Bouna Ndiaye and Jeremy Medjana. At 17, he grew to 6-foot-9, which was when he really began to blossom on defense. Then, at 18, he became a 7-footer, just like his dad.

“One summer, a lot of things changed. The first time I saw him, he was just a different dude. He was a lot taller. He had a different voice,” Fournier says. “It was crazy. Like in one year he just completely changed.”

Gobert’s game changed too. In 2010, he was named to the under-18 French national team, the first honor of his basketball career, not only because of how tall he’d become but because of the talent he’d developed. In 2011-12, he had his best season with Cholet, finally playing for the senior team and looking the part of a potential monster rim protector while making three-quarters of his shots from the field. He had one more strong season with Cholet before entering the draft in 2013. As soon as Gobert grew into his body, he blossomed. Better late than never.

Gobert wears the number 27 to remember how he fell to the late first round in the 2013 draft. Most teams thought of him as raw. “As they say, a project,” Gobert says. But he was. Gobert showed up to his first Jazz training camp weighing only 238 pounds. In front of him on the depth chart were two heavyweights: Enes Kanter, 262 pounds, and Derrick Favors, 265 pounds. “I remember being like, OK, OK. So I need to really take my ass to the weight room and get stronger soon so I can play with those guys,’” Gobert says. His upper body wasn’t filled. He had twig legs. Bigger players pushed him around, and he couldn’t score if it wasn’t a dunk, lob, or tip-in.

While getting in a workout at Utah’s practice facility during an off day, Gobert met Jazz assistant coach Alex Jensen, who was also in his first year with the team. They connected quickly. “Alex was the one guy that I felt like believed,” Gobert says. “Obviously the organization believed in me, or else they wouldn’t have drafted me. But on the coaching staff, Alex was the guy. We naturally got drawn to one another.”

Jensen appreciated how Gobert would be in there every single day. “I don’t have to ask. He’s asking me,” Jensen says. “And he wants to play really bad and he thinks he should. So I thought, ‘This is something you can work with.’” But Gobert wasn’t playing, averaging under 10 minutes while appearing in just over half of the Jazz’s games as a rookie. He missed more shots than he made, and logged more fouls than blocks. Gobert instead started in the G League. But he didn’t want to. He came to the United States to play in the NBA, not the G League. “I saw that as a failure at first,” Gobert says.

Jensen, however, would challenge the premise. “I would ask, ‘Why should you be playing?’” Jensen recalls. Gobert would shrug his shoulders, and just say he can help the team win games. “How?”

Jensen is the only member of the coaching staff who’s been in Utah as long as Gobert, having stayed on after Quin Snyder replaced Tyrone Corbin. The two have grown close. Jensen visits Saint-Quentin for Gobert’s annual basketball camps. Jensen’s wife is friends with Gobert’s mom, and his two young daughters think every basketball player is named Rudy. Gobert calls Jensen “pretty much family,” and it’s important to him that he’s always honest. “Having someone that I feel like tells me the truth and not just what I want to hear, in this league and in life in general, is what I’ve been trying to do,” Gobert says. “I think a lot of guys would rather surround themselves with people that just tell them yes, yes, yes. Sometimes it’s not always good for your growth.”

Gobert would want to work on his post moves. Jensen would have him work on his screening. Gobert would want to practice his shooting. Jensen would have him in the film room watching his pick-and-roll defense.

“He constantly is wanting to get better and sometimes he wants to do everything,” Jensen says. “It’s my role to tell him, ‘It’s not that you can’t do everything, but it’s better if you slowly do this, this, and this.’”

The base the Jazz wanted to build for Gobert has paid off. He now weighs 258 pounds, and has become an integral piece of a team expected to compete for the title. But this summer, after scoring 12.5 points on only six shots per game in the Clippers series, it was finally time to work on refining his offensive game.

In addition to working with Jensen and the Jazz, Gobert worked closely on expanding his at-rim finishing with his personal coach, Fernando Nandes. He practiced power moves so he could create dunk opportunities even if he is well covered, and he worked on touch finishes from awkward angles. But he also tried to get quicker into his moves. There could be no wasted motion. He showed some flashes during France’s run to the silver medal at the Summer Olympics, making some decisive moves to score. Gobert’s most important test won’t come until the playoffs, but the hope is that if a team tries to go small against him again, he could use his size to his advantage and force them to keep a big on the floor to slow him down.

“We worked on everything I can do to punish teams even more. My goal is always to always keep getting better and not put any limits on myself,” Gobert says. “The price of getting better is making mistakes.”

Having someone that I feel like tells me the truth and not just what I want to hear, in this league and in life in general, is what I’ve been trying to do.Gobert

But the Jazz don’t want Gobert taking too many jumpers or post-ups. With Donovan Mitchell blossoming in his own right and a reshaped roster, they just need an enhanced version of the player they already have.

“I tell him all the time, ‘You can dominate the game just by running. If you get ahead of the ball on offense and defense, there’s nobody that can have an effect on the game that you can,’” Jensen says. After getting a stop on defense, the Jazz want Gobert to sprint and make himself a target inside. The mere threat causes defenders to help in the paint, freeing space for shooters.

Gobert has led the league in field goal percentage twice because of how often he’s creating chances at the rim simply running hard up the floor, or setting a screen and rolling hard to the rim. In 2018-19, Gobert set the single-season dunk record with 309, breaking Dwight Howard’s previous record total of 269, which was set in 2007-08. “He’s catching lobs on lobs on lobs, and getting behind the defense. So now teams are like, ‘We don’t want him to break the dunk record, we don’t want him to get 20 points on all dunks,’” Mitchell says. “You take it away by helping off of the shooters. But now we have shooters in those corners who can make those shots. Now it’s more indecision, which started with Rudy winning the dunk record.”

For years, Gobert’s rolling and running has created a “conundrum” for the defense, Jensen says. “You have to scheme not necessarily for our other guys but for how you’re going to play Rudy,” he says. “If you’re going to play us, ‘OK, what are we going to do about Rudy?’” Playoff teams have found some answers to that question, though. After changes to the roster and another summer of workouts for Gobert, he and the team hope they’re able to go deeper in the playoffs this time around.

When Gobert isn’t helping the Jazz try to win games, he’s still playing video games. Over this past year-plus, his favorite game has been Call of Duty: Warzone, a battle royal game with 150 people playing solo or in teams, all with the mission of being the last to survive. Like basketball, it’s a game that requires strategy, communication, teamwork, movement, and skill.

It’s also a good way for him to connect with teammates like Mitchell, Royce O’Neale, and newcomer Hassan Whiteside. Gobert has a 1.1 kill-death ratio, ranking in the top 22 percent for all players, and he loves sniping—perhaps because he doesn’t get to take many long-range shots on the basketball court. But he brings some of the same qualities as a communicator, calling out and marking where enemies are so he or his teammates can eliminate them. “You don’t get an assist. You don’t get nothing,” Gobert says. “Or you throw a great stun, and they finish the job.” In Warzone, these are the basketball equivalent of winning plays.

Open communication was a key in mending his relationship with Mitchell. In March 2020, before Gobert knew he was the first NBA player to test positive for the coronavirus, he jokingly touched reporters’ microphones at a Jazz news conference. Safety restrictions were being put into place that would keep media from interviewing players in person, and he thought he was lightening the mood in the room. Soon, Mitchell himself tested positive. Mitchell was openly annoyed about the way things transpired, and The Athletic reported the relationship was “unsalvageable.” Tensions were high for everyone around the world at the time, but the teammates talked before going to the Bubble. Gobert admitted he made a mistake. The All-Star duo moved on and sources around the Jazz say it hasn’t been an issue since.

Now, Gobert and Mitchell are hoping to lead the Jazz over the top in the playoffs together. Mitchell will do most of the scoring, but he appreciates Gobert’s beyond-the-box-score impact. “People don’t pay attention to that. It’s a lot of information that people don’t really want to hear about,” Mitchell says. “But it definitely doesn’t go lost in this locker room.”

Zoom out from the playoff series losses and you’ll see that Gobert is on a Hall of Fame career trajectory, one that follows the path blazed by elite defenders in their era, such as Ben Wallace and Dikembe Mutombo. Jensen once told Gobert he could make tens of millions in his career. He laughs about that today, considering Gobert will make hundreds of millions.

“I think anybody that envisioned him where he is today would probably be lying,” the Jazz assistant says.

Anybody other than Gobert, that is. Whether it’s winning a game console or making it to the NBA, he sets his goals high and grinds to get what he wants. “I never let critics or people who made fun of my dreams discourage me,” he says. “Actually, it was always the opposite. It fueled me even more.”