The two championship series games on Tuesday night were scheduled to begin three hours apart. Theoretically, that gap left enough time for baseball fans to watch all of both games—a modern MLB game, after all, is “supposed” to last about three hours.

But that assumption isn’t true anymore, and it isn’t true in the postseason, especially. At the time of first pitch in Fenway Park, home of the second game of the night, the opener in Dodger Stadium was just entering the seventh inning. At the time of last pitch in the latter game, more than four hours after it started, the former was already in the bottom of the third.

The extreme game length that caused this overlap and prevented fans from devoting full attention to both crucial contests is not an aberration, however, but the new postseason norm. The average playoff game this postseason has lasted a gobsmacking three hours and 42 minutes.

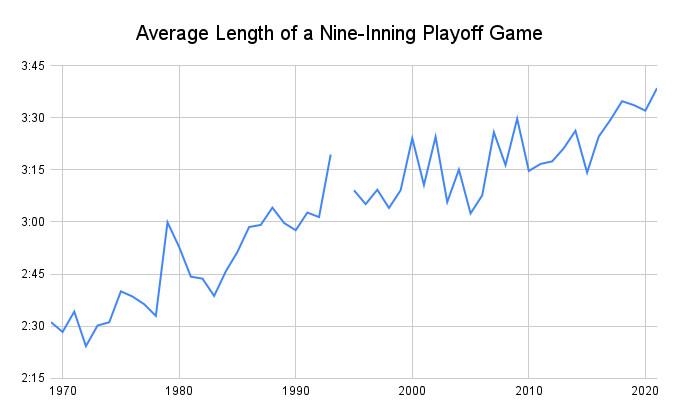

Remove the 13-inning, five-hour-and-14-minute battle between the Red Sox and Rays, and the average for nine-inning contests is still an absurd 3:38, the highest ever. This graph shows how the average nine-inning playoff game length has changed since 1969, the first season with intraleague playoffs before the World Series.

Game length has almost always increased, but now that increase is accelerating, too. From 1991 to 2001, the average playoff game increased by eight minutes. From 2001 to 2011, the average playoff game increased by six minutes. But from 2011 to 2021, the average playoff game has increased by 22 minutes. And that’s probably an undercount because the 2021 playoff data doesn’t include the World Series yet, and those games tend to last the longest of any round.

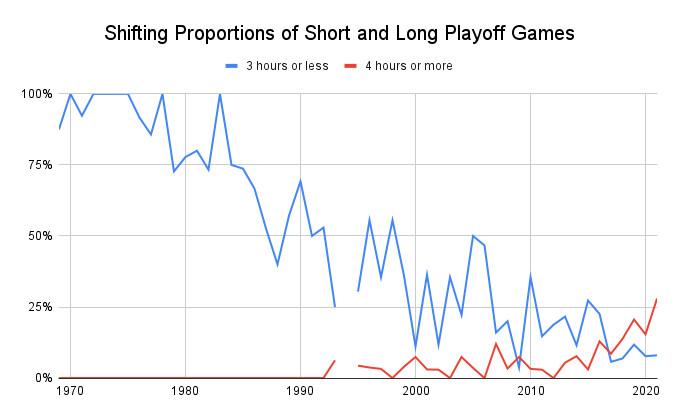

The only individual game this postseason to last less than three hours was Giants-Dodgers Game 1, when Logan Webb worked quickly to shut out L.A. for seven and two-thirds innings. Milwaukee-Atlanta lasted three hours on the dot, as Corbin Burnes tossed six shutout frames. Every other game this postseason has lasted longer than three hours.

Game length has shifted in the other direction instead. The first nine-inning playoff game to last more than four hours was understandable: Game 4 of the World Series between Toronto and Philadelphia finished with a 15-14 score, and all those runs took 4:14 to score. But the four-hour playoff game has since become endemic, to the point that playoff games are now far more likely to last four hours or more than three hours or less.

There were seven four-hour, nine-inning playoff games in 2019, eight in the expanded playoffs in 2020, and seven already in 2021. That tally includes this year’s NL wild-card game, which ended after 4:15 with a score of 3-1—a far cry from the 15-14 shootout that first necessitated such a lengthy game.

Such length meant that baseball fans who wanted to watch Chris Taylor’s walk-off homer needed to stay awake until 12:25 a.m. in the Eastern time zone, or 11:25 p.m. in St. Louis. That’s a tall ask for any spectator, especially children.

Complaints about the length of baseball games because won’t somebody please think of the children are nothing new. I remember missing playoff games from my favorite team two decades ago because they lingered well past my bedtime. Yet as MLB attempts to appeal to a younger crowd, those concerns aren’t just rhetorical, but actually matter a great deal. How many young Atlanta fans were awake to watch their team walk off in Game 1 of the NLCS at 11:12 p.m., or in Game 2 at 11:34? Positioning the sport’s future fans to miss the most important moments is no way to grow an audience.

Of course, games can’t start too early, or else the adult fans who have to work during the day won’t be able to see their favorite team play, either, let alone pack the stands for home games. (Game 3 of the NLCS started at 2:08 local time in Los Angeles, and the crowd didn’t sell out.) But the current setup isn’t ideal for adults, either, nor the reason they became fans in the first place. The average age of MLB fans, according to one survey, is 57 years old. Said average fans would have developed their interest in the sport in the early 1970s—when playoff games took about two and a half hours to play, more than an hour less than games take now.

The solution, then, is to try to cut game time. Enter the pitch clock.

In 2017, Grant Brisbee watched and timed two nondescript regular-season MLB games, one from 1984 and one from 2014, each with the same number of runs, pitches, base runners, and batters. The more recent game took 35 more minutes to play, and 25 of those extra minutes came from greater time between pitches. (The rest of the extra time was roughly split as six additional minutes from breaks between innings and four minutes of a replay review.)

That’s just one anecdotal example, but in the Low-A West minor league this season, a pitch clock experiment that forced a faster flow between pitches—15 seconds to throw with nobody on base, 17 seconds with a runner on—cut the average game time by a similar amount. Before the installation of the pitch clock in midseason, games were averaging 3:02. After? Just 2:41, a difference of 21 minutes.

Clearly, a pitch clock would have an impact at the MLB level, too. According to estimates provided by Baseball Prospectus, 82 percent of MLB pitchers abided by a 15-second limit on average with bases empty in the regular season, but just 15 percent abided by a 17-second limit with runners on base. (These figures aren’t exact because it’s difficult to determine exactly when the pitcher receives the ball from the catcher to start a hypothetical clock, but the general pattern should hold.)

A pitch clock seems even more necessary in the playoffs. Entering Tuesday’s games, pitchers were taking an extra 2.5 seconds between pitches with bases empty and an extra 3.1 seconds between pitches with runners on this postseason, relative to the regular season, according to BP data. Spread over about 150 pitches per team per game this postseason, that’s an extra 13 or so minutes per contest because of languorous pitcher pace alone.

Some pitchers are particular offenders. In this postseason, Lucas Giolito added an astounding 10.1 seconds between pitches with the bases empty and 10.6 with men on. Closers Kenley Jansen—already one of the most deliberate pitchers in the majors—and Will Smith have added a few seconds apiece. Even relatively speedy pitchers aren’t immune to playoff inflation: Tanner Houck was one of the quicker pitchers in the majors in the regular season, but has added 6.9 seconds between pitches with the bases empty in the playoffs.

Granted, a pitch clock might not prove a panacea, especially if it isn’t as aggressive as that in the Low-A West league. A more flexible 20-second pitch clock at Double- and Triple-A, which applies only with the bases empty and can be reset if the pitcher steps off the rubber, initially cut game times, but they have crept back up ever since. And with the bases empty, most MLB pitchers are already below the 20-second average, anyway.

But at this point, the powers that be have to do something. A baseball fan who wants to watch full games for both the ALCS and NLCS on the same day must now commit in the range of eight hours to the project, multiple days in a row. Who has that kind of time on weekdays?

Some factors inherent to the postseason necessarily increase game length: Commercial breaks are 50 seconds longer in the postseason than the regular season, which adds about 14 minutes to a game, plus the high stakes of postseason play generally mean more pitching changes and deeper counts. And this postseason, the American League playoff games have lasted longer than their NL counterparts because of record-setting offense.

Yet even if we accept the premise that postseason games will last longer, the regular-season baseline is now so high that playoff games can’t help but take an eternity apiece. The average nine-inning game in the 2021 regular season lasted 3:10, the longest ever; after a momentary drop for the 2018 season, when MLB implemented a few changes like limiting mound visits and using a timer for between-innings breaks, the average time of game has increased three seasons in a row.

Like the broader “baseball is dying” refrain, these sorts of pace concerns have been baked into the sport’s discourse for decades. “Baseball Games Take Too Long,” warned a newspaper headline on August 4, 1951, the same year that the average nine-inning contest lasted—heaven forfend!—2:19. In 1936, when the average length of a nine-inning game clocked in at all of 1:58, Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby complained that “games take too long.” The previous postseason, four of the five nine-inning World Series games had finished before the two-hour mark.

That history suggests baseball will survive even as games extend longer and longer, but an entertainment product should aim to thrive, not just survive. And for those who are fundamentally opposed to the addition of a clock in the “timeless” sport, how much is too much? Is 3:40 across that threshold? What about four hours per game? Four hours, twenty minutes? There’s probably a practical limit to the length of an average baseball game, but the current trend line just keeps pointing in the same direction.

Speaking of that trend line: After L.A. outlasted Atlanta in 4:14 on Tuesday, Houston needed 4:04 to beat Boston, with the game ending after midnight at Fenway. Forget a three-hour scheduling window to prevent games from overlapping—now even a four-hour window isn’t enough.

Thanks to Jonathan Judge and Harry Pavlidis of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.