I’m no fan of Halloween as a holiday. The prep work, the pressure to have fun, the drunken hordes—it’s not for me. It’s ironic, then, that my favorite string of sitcom episodes is based around the occasion—or perhaps not. You don’t have to like dressing up or drinking games to appreciate a well-crafted piece of television. And over eight seasons on two networks, Brooklyn Nine-Nine built its annual Halloween heist into a shining example of an underappreciated art form: the sitcom holiday episode.

The “holiday” in “holiday episode” can take many forms. Some are entirely invented, like Seinfeld’s Festivus. Some are unconventional markers of conventional occasions, like 30 Rock’s giddy celebration of Leap Day. And some are running franchises that recur year after year, like Friends’ vaunted Thanksgiving episodes. The Halloween heist saga isn’t even the only one centered on All Hallows’ Eve: The Simpsons has its famous Treehouse of Horror specials, which gave us the immortal GIF of Homer eating infinite donuts, while shows as diverse as Bob’s Burgers and Home Improvement have their own repeating traditions.

When done well, the holiday episode is a break from a show’s status quo that still preserves its equilibrium—an important injection of novelty into a nine-month, 20-plus-episode season, but not so much novelty that it scrambles the series’ DNA. Given that connection to a linear broadcast schedule, it’s also increasingly nostalgic; some streaming shows do have holiday episodes, but they’re neither as relevant nor as impactful as one released in real time. The BoJack Horseman “Christmas special” is an excerpt from its show-within-a-show rather than an update on the main plot, the TV equivalent of a bonus track; it’s possible the Ted Lasso Christmas episode would have gone over better if it hadn’t been released in mid-August.

From its premiere on Fox in 2013, Brooklyn Nine-Nine did its best to form a bridge between TV’s past and future. It was a traditional workplace comedy on a traditional broadcast network, but with a pointedly diverse cast; it was a show about cops that tried to advance a progressive, optimistic vision of what policing could look like. In the wake of last summer’s protests, the latter proved too great a burden for the lighthearted hangout to bear, hence why the abbreviated final season ended somewhat silently last month, just a few years after NBC saved the show from cancellation to widespread acclaim. But the Halloween heists are largely internal affairs, centered on the core cast and light on the knotty questions that haunted the show and ultimately overshadowed it. The episodes are as good a legacy as any to remember the show by—and as good a standard to judge its track record against other sitcoms’, now that it’s complete.

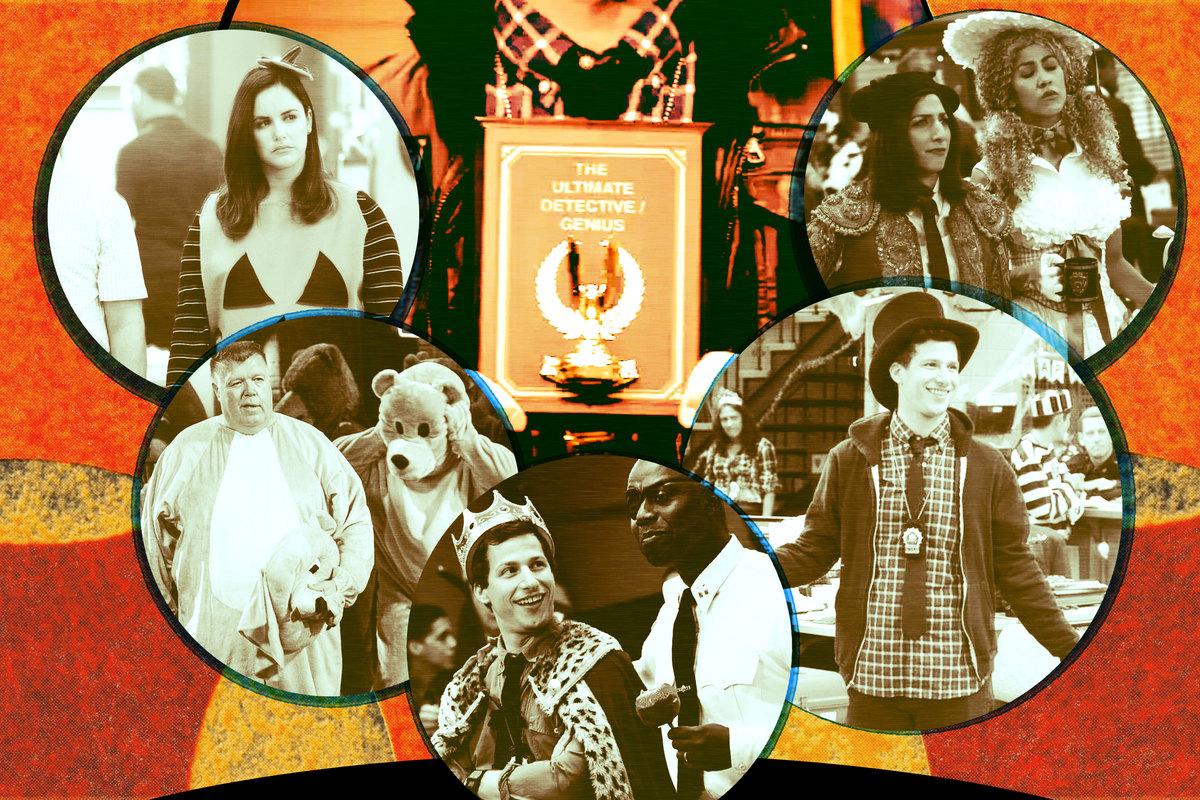

The first Halloween heist goes down in Brooklyn Nine-Nine’s sixth-ever episode, awfully early to lock in a template that would last the life of the series. (Parks and Recreation didn’t come up with Treat Yo’ Self Day until Season 4!) The premise is a direct extension of the show’s primary arc: Detective Jake Peralta (Andy Samberg), overconfident man-child, craves the approval of his new boss, Captain Raymond Holt (Andre Braugher), so he invents a pointless challenge to prove himself “the ultimate detective-slash-genius.” Jake vows to swipe Holt’s treasured Medal of Valor from his office by midnight or else work five weekends without overtime pay. Though it seems doubtful the NYPD’s union contract would even allow for such a trade, Holt agrees.

The first heist contains traces of what the series would become: convoluted schemes, dramatic reversals, maximum investment in minimum stakes. (Jake wins, secretly enlisting the rest of the squad in a plan involving live pigeons. Holt is begrudgingly impressed.) But it’s also very much a rough draft, an enjoyable episode of TV without the résumé to draw on its own legend. For one thing, it’s more overtly Halloween-centric than later incarnations, featuring a Mario Batali costume that’s aged like milk and detectives dealing with inebriated chaos, a subplot that gives the episodes their unofficial motto: “Friendships are forged in the crucible of Halloween adversity,” Boyle (Joe Lo Truglio) advises Amy (Melissa Fumero). “Halloween” doesn’t even end on the heist, dedicating near-equal time to B- and C-plots with other combinations of characters. The event isn’t enough to hang an entire episode on by itself, or at least it isn’t yet.

But over time, the heist takes on a gravitas of its own. First, Boyle is the only character who bothers dressing up; even that slowly gets phased out, along with the running gag where no one recognizes his costume, however obvious. By Brooklyn Nine-Nine’s middle stretch, a few decorations in the background are the only hint of the high jinks’ topical peg. The show dispenses with the expected rites of Halloween revelry. It also preserves the sense of fun that can still make Halloween a good time, beneath all the baggage. Even Halloween haters can get into it, in noted contrast with the festivities around Christmas (which can be alienating for those who don’t celebrate—the noted “rest of us” in “Festivus”) or Thanksgiving (an awkward colonial backstory most comedies don’t bother to take on, though I’d love to see Rutherford Falls, whose cocreator once wrote for Nine-Nine, take a swing). There’s also much less pressure placed on Halloween to begin with, making it the ideal holiday to push the limits of in the first place.

For the last three seasons, the heist doesn’t even take place on Halloween, shifting instead to Cinco de Mayo, Easter, and finally, the series finale—a testament to just how integral the heist became to Brooklyn Nine-Nine as a whole, not just its seasonal milestones. With every iteration, the heist gets more elaborate and more competitive, splintering from a two-way contest into a free-for-all with every man and woman for themselves. (The title, retooled to “ultimate human-slash-genius,” eventually passes between most of the series regulars.) Like any sitcom conceit that goes on long enough, it also gets meta. “You know that fun, braggy recap we do?” one character asks, referring to the explanatory montage of any good heist sequence. “You Mission Impossible’d me!” another crows of a fake-out involving a constructed set. Once a model is set enough for viewers to anticipate, the writers can start having fun with it.

Though the heists are, like most sitcom episodes, relatively stand-alone, there are exceptions. The fifth iteration ends with Jake’s proposal to Amy, which she naturally assumes is a tactic before she says yes. And the finale ends by promising the heist will continue year after year, even if we won’t be around to see it. Consistency is a hallmark of a successful sitcom; it’s what gets a show to the all-important syndication milestone of 100 episodes, which Brooklyn Nine-Nine passed in Season 5. And consistency is what the Halloween heist provides, even as the show persistently upped the ante and made tweaks to the formula. In real life, holidays don’t always live up to their promise: something to return to, a gathering place for a diffuse group of friends. On TV, holiday episodes fulfill it for us—even on Halloween.