Somewhere, buried in the first half-hour of The Harder They Fall, the new Netflix Western, Trudy Smith (Regina King) reigns atop a horse, its hooves planted on a pair of train tracks. The whistle of an oncoming steam engine grows louder in the distance as a light flurry of snow dots the frame. The camera cuts to the locomotive hurtling down the tracks. It blares its horn, barrels forward a bit, and hisses. The lens homes back in on Trudy’s face. She doesn’t budge. She doesn’t even blink. OK, she might blink—forget the blinking; the blinking doesn’t matter. They’re in a staredown, this hunk of speeding steel and this woman on a horse. With every passing second, so are the viewer and the film—caught in a battle of wills. What’s at stake is whether or not you can actually manage to look away.

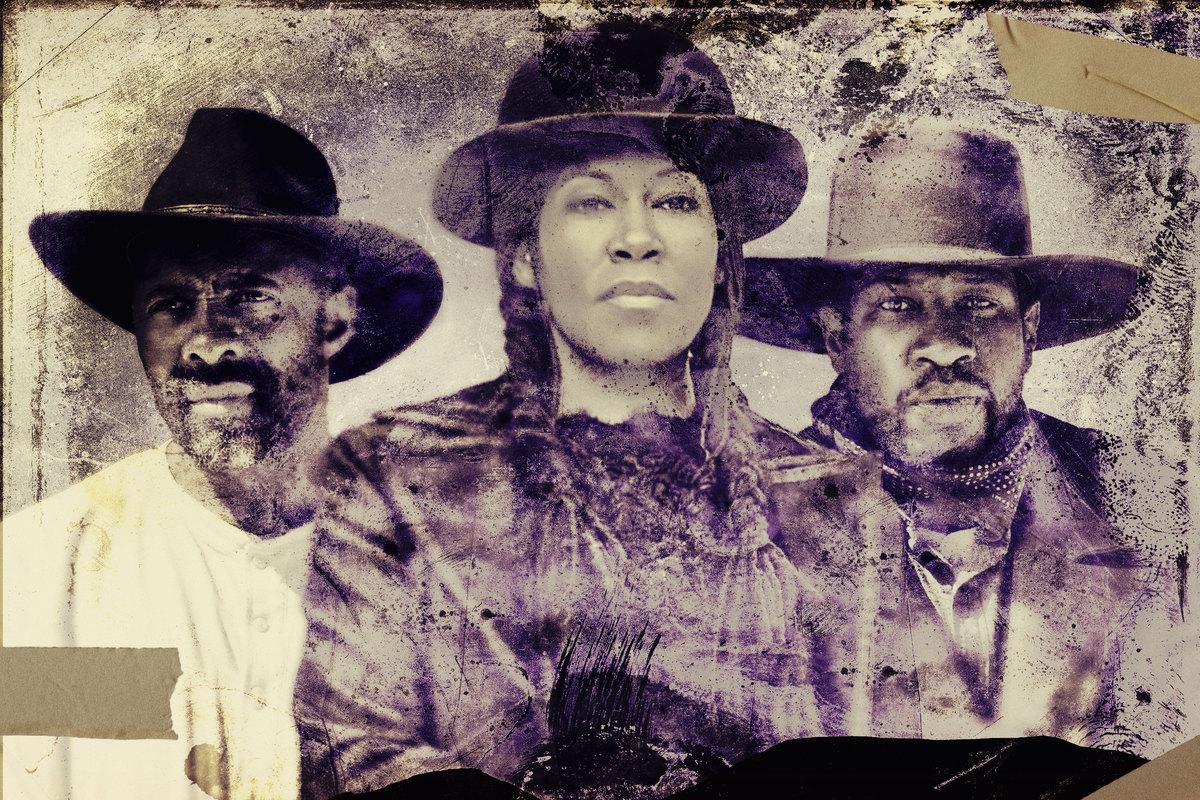

Directed by Jeymes Samuel, The Harder They Fall revels in the art of attraction and the seduction of drawing and holding a collective focus. The film follows Nat Love (Jonathan Majors), a young gunslinger who dedicates his life to avenging the childhood murder of his family by a hulking outlaw named Rufus Buck (Idris Elba). Trudy is waiting on the railroad to bust Rufus out of captivity, which sets in motion the rest of the plot. The Harder They Fall centers on a strain of history that—while explored repeatedly by Black filmmakers—has been virtually erased from mainstream (white) Western iconography: the Black cowboy and outlaw. (Nearly all of the characters in the film are named after real-life figures.) The film’s subject matter and its majority Black cast and crew has led the film to be typified as a kind of symbolic triumph, like so many other recent Hollywood works created or populated by marginalized people. Since the movie’s release, the coverage of The Harder They Fall has centered on the film’s attempt to subvert the most popular and exclusive format in the history of American cinema. But all of that discourse doesn’t mention what actually unfolds onscreen.

The highs of The Harder They Fall are standard for a Western, and still, they never feel canned. Samuel furnishes the film with wide shots of dusty canyons and lurking mountains and overhead views of riders galloping in angular formation. The landscape evolves beyond a background and into the core of the story itself. In the movie’s second act, a night spent camped on a cliff indicates a figurative precipice in the narrative. Later, Nat and Cuffee (Danielle Deadwyler), a member of Nat’s recently formed outfit, are forced to infiltrate and rob a bank in a nearby white town. The storefronts in the hamlet are hued alabaster. In The Harder They Fall, something as simple as a building’s color can convey as much about the values of its inhabitants as any single utterance. Close-ups are wielded to ground the work in the interiority of its characters. Even the sounds at hand—a gun clicking, a steak being chewed, lips smacking, flesh and bone tearing—all imbue The Harder They Fall with the kind of detail that makes a Western soar.

Despite the occasional frenzy, though, it is an overwhelmingly quiet film. The tranquility of remote regions (and how it can be shattered) has long been common tunes of the genre—think the pervading wordlessness of a Sergio Leone film or Unforgiven’s ever-so-orderly sound palate. That the West was never actually that still, never actually that sparse, is inherent to its appeal. The Harder They Fall seems to understand that the Western is a dream defined in equal parts by truth and fable.

The movie’s shoot-outs appear fantastical, as if to dilute the very specter of death. In one nifty long-range clash, a kill shot is displayed from the perspective of the victim-sniper’s binocular. Later, Nat and Mary (Zazie Beetz) conclude a fray back-to-back, mowing down oncoming members of Buck’s gang as if they’re in a Red Dead Redemption cutscene. The quintessential Western showdown appears sparingly throughout the film, and is ended on multiple occasions with such immediacy that only one competitor has time to draw their gun. Elba, for his part, utilizes every bit of his shape to play the villain, instilling an inescapable sense of hunger and danger in Rufus.

Yet not everything in The Harder They Fall is smooth. The dialogue, particularly as the film inches toward a conclusion, can feel hasty. (The romance between Nat and Mary is, increasingly, a drag.) There are moments when it seems as if the movie is more concerned with ensuring that viewers attach themselves to its characters than understand them. We never really learn why Trudy is so steadfast in her faith in Rufus. Why Nat’s gang is willing to follow him, perhaps to their death, remains similarly unclear.

There are things that happen in the movie’s final act that make little sense. Just as Nat and Co. have located Rufus and the rest of his gang, in a narrative choice that serves no reason other than to move the plot along, Mary attempts to infiltrate the town where Buck and his gang have holed up. What follows is a variation on the damsel-in-distress trope, a move that’s more boring than it is offensive. The film ends on a twist that could’ve worked in the abstract if not for the fact that it’s the least interesting part of the entire story—which is proof of both the film’s flaws and its capacity to excel. The Harder They Fall is absorbing enough that the finale hardly matters, so long as the plot keeps rolling.

Isn’t that—more than tumbleweeds or guns, saloons or showdowns—as conventional a pitfall as a Western can have? Aren’t they always, in one way or another, just a bit messy? Pretty enough, or daring enough, or just plain contemplative enough to mask how contradictory the myths at the root of the art form are. (Whenever we talk about cowboys or gunslingers, it ain’t like we’re really talking about cowboys or gunslingers. Clint Eastwood didn’t make a career out of interrogating land theft and Indigenous genocide, but that was the unspoken subtext of his exploits.) The Harder They Fall is an inconsistent but generally thrilling film, with the type of highs that can excuse some lows. And that appears to be all it wants to be. It is historical, but only to a point. In other words, it’s like basically every other cowboy flick.

The Harder They Fall may or may not expand what a Western can be, and that says far less about the film itself than the genre at large. The movie, for its part, doesn’t feel particularly concerned about the context or meaning of its own arrival. Just before the credits, right as the camera pans out of a sandy ridge, Trudy makes a final appearance, skulking in the corner. She’s not supposed to be there. She should be gone. That she isn’t seems to hint at the possibility of more stories to come in this universe. In The Harder They Fall, more than any cause or promise, the reason to head West is that it’s worth the ride.