The Complete History of the Kings and Queens of New York Rap

The throne of hip-hop’s mecca: Biggie forced the issue, Jay-Z coveted it, DMX had a brief reign more spectacular than anyone else’s. But in the more than 40 years since rap music was first committed to wax, the crown has sat on many heads. Here, we trace that lineage from Grandmaster Caz through the muddled modern day.On Thursday, Ringer Films will debut the latest installment of its HBO Music Box series, DMX: Don’t Try to Understand. Over the next few days, we’re chronicling the rapper’s rise and place in hip-hop history. Today, we’re looking into the lineage of the kings and queens of New York rap, a title DMX held in 1998 and burnished like no one before him or since.

To coincide with the release of DMX: Don’t Try to Understand, we set out to give the proper context for where X fits in the annals of New York rap. While record sales are one thing—and those videos of him controlling thousands of fans like a marionette are another—it’s difficult to quantify just how monstrous his impact was in 1998, the year he dropped two chart-topping albums and knocked hip-hop, and the industry around it, off its axis.

So we looked back and forward from that midpoint—from recorded rap’s beginnings in the late 1970s all the way through the present—to pinpoint who, at any moment, was the king or queen of New York rap. Some reigns are years long and others last a handful of weeks; all had a creative and cultural impact that helped shape a genre and a city.

This exercise is not perfect and does not provide a holistic view of rap in New York in any given year. It naturally does not document any of the underground movements that, collectively, come to be just as crucial as any single star. Sometimes two deserving artists reach the height of their powers at the same time; sometimes, as with Ghostface (and debatably with Cam’ron), a rapper’s time on the throne does not align with his or her creative peak. A critical reader might have questions like “How could this model be tweaked to reflect the contributions of someone like Kool Keith?” Or “Where the fuck is Prodigy?!” But this project is not aiming for a universal lens—instead it’s trying to identify those moments when a rapper’s supremacy becomes unquestionable.

What it does is trace the chain of custody, like a title belt in boxing, of that elusive thing that DMX had in 1998. At times, there is no king or queen of New York—other times two, three, or five people might have credible claims on the title. But tracking this speaks directly to one of rap’s most romantic appeals: the ability to capture, on record and for posterity, the fits of inspiration that once were the ephemeral draws of house parties and park jams.

Grandmaster Caz (1979)

It was Grandmaster Caz who first rapped and DJed simultaneously, practically serving as a one-man transitional phase for the genre as its focal point moved out from behind the decks. While he and the other Cold Crush Brothers were in demand as performers—and the Bronx-bred Caz in particular was widely recognized as one of the premier rappers of the moment, with his metronomic, quickly paced rhymes presaging the more complex internal patterns that rappers like Rakim would later perfect—they were ambivalent about cutting records. So when their manager, Big Bank Hank, passed Caz’s lyrics off as his own on the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” there was as much confusion as outrage about the commercial breakthrough by a group of unknowns. Years later Caz would recall saying, upon hearing the song that cribbed from his notebook: “Who the fuck is they?”

Kurtis Blow (1980)

After studying the proto-rapping of pioneers like DJ Hollywood, Harlem’s Kurtis Blow fused hip-hop’s disco roots with street-level reportage. His deal with Mercury made him the first rapper signed to a major label, and “The Breaks” is recorded rap’s first masterpiece: tragic and comic, its grievances alternatingly petty and gothic.

Melle Mel (1981-82)

On July 13, 1977, New York City went dark. From about 8:30 p.m. through the morning of July 14, virtually the entire city was without electricity. There was naturally a lot of small-time crime under the cover of darkness, some of it vital to hip-hop’s development: Grandmaster Caz claims to have liberated at least one mixing board from an electronics store, with countless other producers and DJs rumored to have done the same. Whatever the hardware situation, it was that post-blackout morning when a Bronx teenager named Melle Mel officially joined forces with an iconic DJ and handful of other young rappers to form Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five.

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, the group performed constantly and cut a handful of records, including the crucial singles “Superrappin’” and “Freedom.” But in 1982, Melle Mel tweaked the group’s approach—and expanded the possibilities for rap as a vehicle for sociopolitical commentary. “The Message” (and its unnerving documentary video) pays off what “The Breaks” merely suggested. Its view of poverty and social immobility in New York is as panoramic as it is nihilistic: bill collectors terrorizing debtors, dead bodies swinging like pendulums in jail cells. “All the buildings was burnt out,” Melle Mel would later say, recalling the Bronx of his youth. “It looked like a war zone.” “The Message” was an urgent dispatch from the front lines.

Run (1983-84)

The tracksuits and gold ropes might have come from Jam Master Jay, the punishing bass from Larry Smith, and the more-than-capable counterpoints from DMC. But it was the Hollis, Queens–born Joseph “Run” Simmons who became the fulcrum around which rap pivoted after his group’s 1983 debut. Once a DJ for Kurtis Blow—and, crucially, the younger brother of Russell, who would go on to found Def Jam—Run’s rhyme style was more urgent, more staccato than that of his predecessors. Perhaps more importantly for this project’s purposes, he was the first rapper to make the sucker MCs in his rhymes into abstract, nearly mythic foes rather than some person he might have run into at a club in the Bronx. He made the question “Who is the best rapper alive?” an existential, rather than clerical one. Run-DMC’s commercial peak would come later, with 1986’s Raising Hell, which was produced by Rick Rubin and featured the “Walk this Way” duet with Aerosmith. But by then New York was bending toward younger rappers with ever more intricate styles and slang. It’s the early, swaggering, Larry Smith–produced work that cements Run’s place in the canon.

Roxanne Shante (1984)

If you leaf through history books, you’ll find some royals who bided their time before taking their thrones by force, and others who were thrust into power when they barely into their teen years. Roxanne Shante is both, a preternatural talent who staged a coup when she was just 14. That was the year the Queens native bumped into Marley Marl and the legendary DJ Mr. Magic; together, they hatched a plan to record a response to U.T.F.O.’s “Roxanne, Roxanne.” “Roxanne’s Revenge” not only launched Shante’s career, but sparked the Roxanne Wars, an endless string of response records that smuggled rap’s battle ethos onto wax.

LL Cool J (1985)

LL Cool J raps like he was dropped in a vat of charisma as a child. Just as importantly, he spent his formative years in Queens studying early hip-hop, a fixation his family encouraged: His mother scrounged money to buy him a drum machine, and his arsenal of hardware was rounded out by his grandfather, a jazz saxophonist. By the time he was in high school, he was cutting his own demo tapes and lobbing them to record companies; he landed at the newly formed Def Jam, and 1984’s “I Need a Beat” was the second rap single the label ever issued. Radio, released late the following year, made him a superstar.

LL’s debut was produced almost entirely by Rick Rubin, whose beats are confrontationally spare (his credit on the LP’s back cover reads “Reduced by Rick Rubin”). Their monstrous low ends are balanced by LL’s vocals, which brim with personality—the raps are forceful, but their edges are sanded down just a bit when compared to Run’s rawer early work. Radio was merely the first of six platinum albums that LL would release through 1997, and he would continue to be a highly visible rapper and actor into the 2010s. But the commercial breakthrough that his first album represented would spawn rappers who surpassed him, either in terms of sheer celebrity or pointed opposition to it.

KRS-One (1986-87)

In 1985, when LL was finishing his first platinum record and buying his nth gold rope, a teenager named Lawrence “Kris” Parker was scamming his way into a different kind of metal. A resident of the Franklin Avenue Armory Men’s Shelter on 166th St. in the Bronx, Kris would claim phony job interviews to receive free subway tokens from the shelter’s employment program. One social worker, Scott Sterling, sniffed out the grift and confronted Kris; the two got into a shouting match so heated they had to be separated by building security. Weeks later, the two had become inseparable—as KRS-One and DJ Scott La Rock, the founding members of Boogie Down Productions.

BDP cut some demos; early listeners, including Mr. Magic, were indifferent. So when Magic’s Juice Crew compatriot, MC Shan, released a single called “The Bridge,” KRS was all too eager to fire back, even if doing so required a willful misunderstanding of the song’s lyrics. Shan has always claimed that the story, in “The Bridge,” of “how it all got started way back when” is merely him telling the story of how rap in Queensbridge began, rather than making the claim that hip-hop began in Queensbridge. But KRS’s responses—“South Bronx” and especially “The Bridge Is Over”—vaulted him to the top of New York; his careening vocals, which flaunted his Jamaican roots, boomed across the boroughs.

KRS would go on to cement himself as one of the greatest rappers ever, with an extensive catalog and unshakable, if sometimes rigid perspective, but Scott La Rock would tragically not live to see this. In 1987, just a few months after the release of BDP’s staggering debut, Criminal Minded, he was killed after trying to mediate a feud between the other BDP member, D-Nice, and a pair of men. He was 25.

Rakim (1987)

There is studied cool and then the kind that can’t be taught; Rakim excelled in both categories. A naturally charming high school quarterback on his native Long Island, Ra would also pore over the dictionary and pages of notebook paper, which he divided into grids so that the syllables in his raps would land just so. Though hungry for opportunity, he would not pander to an audience, no matter how distinguished it was: When he got a chance, as a high schooler, to record in the already legendary Marley Marl’s home studio, he sat on a couch to lay his vocals, refusing Marley’s urges to rap more animatedly—advice that was echoed by the similarly revered MC Shan, who dropped by the session and was similarly ignored. That unshakable poise preserved a truly distinctive voice. Paid in Full is the greatest rap album of the ’80s. Ra’s cutthroat perspective, Five Percenter teachings, and—most importantly—his intricate internal rhymes mutated the form forever.

Slick Rick (1988)

By 1988, Slick Rick was already something of a legend. “La Di Da Di” had been a hit for two summers: It was on tapes and mix shows in ’85 and on radio in ’86. That single earned him a reputation as hip-hop’s first great longform storyteller; you wouldn’t have to look hard to find people who claim that his first LP, The Great Adventures of Slick Rick, is still the apex of narrative writing in the genre.

Rick’s own life story reads like a parable. Born in London, blinded in one eye by broken glass as a baby, and ferried to the Bronx just as rap was beginning. He absorbed the culture but retained that lilting accent; he covered the eye first with a utilitarian patch, then ones that were studded with diamonds. Later there would be two stints in prison and marathon battles with immigration services. But at his sharpest, Rick was as inimitable a writer as he was a vocalist, his tales as uproariously funny as they could be unbelievably grave. See “Children’s Story,” which is at turns sarcastic and shockingly violent, a tidy little bedtime tale that ends with the police murdering a 17-year-old. Rick raps: “I still hear him scream.” Then he tucks the kids in.

Chuck D (1989-90)

Where many of rap’s early stars were shockingly young—LL and Rakim got their starts in high school, Run-DMC broke through when that pair had just started university—Long Island’s Chuck D was a college graduate and veteran DJ before Rick Rubin came across one of his demos and lured him to the then-upstart Def Jam, and he was about to turn 27 when Public Enemy’s debut, 1987’s Yo! Bum Rush the Show, was released. Though authoritative and frequently engaging, that album might have seemed an immediate relic—Chuck’s political discontent rendered in cadences that were rapidly becoming obsolete over early Bomb Squad beats that skewed too often toward the circa-’85 Def Jam style that Radio typified.

It was Public Enemy’s sophomore record, 1988’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, that transformed the group into one of the most vital the genre would ever see, and Chuck into one of its most inimitable voices. While the beats grew stranger and more serrated, Chuck sharpened his writing, taking vicious swings at the press, the lawyers, and the feds. (That final group was the target of the finest Public Enemy song, “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos,” which opens, unforgettably: “I got a letter from the government the other day / I opened and read it, it said they were suckers.”) Backlash to the group’s political affiliations rattled Chuck only momentarily; PE returned the following year with “Fight the Power,” which soundtracked Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and distilled his mission statement into a single song.

On 1990’s Fear of a Black Planet, The Bomb Squad’s ravenous sampling became cacophonous in the best way—a way that would become legally impossible in the years to come—and Chuck’s command of his cannonlike baritone only deepened. (So did his interplay with the other PE members; look no further than the way he and Flavor Flav play their vocal tones off one another’s on the opening line of “Fight the Power.”) As a songwriter, Chuck showed how to explore each nook and crevice of his psyche without conceding to a political or aesthetic middle. He did not compromise—he doubled down.

Rakim (1991)

While Rakim’s first two albums vindicate his choice, made on Marley’s Marl’s couch, to preserve the placid voice Marley tried to turn more aggressive, 1990’s Let the Rhythm Hit ‘Em belatedly allows some of that agitation to seep in. Rakim’s deeper vocal tone on Rhythm, ’92’s “Know the Ledge,” and the same year’s Don’t Sweat the Technique implies a fury that only he could harness so effectively and use to reclaim the throne he’d relinquished.

Kool G Rap (1992)

From “The Breaks” on, the crime rendered in rap music has been treated as literal truth—by white critics unwilling to grant creative license to Black artists, by cops trying to pin charges on rappers, and by voyeuristic fans. Kool G Rap challenged this by writing harrowing crime tales that played like pulp novels or mob pictures, the violence heightened and stylized, the stakes dizzying but ready to reset when the tape turned over. The mafioso bent to New York rap in the mid-’90s—everything from Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… to It Was Written, from the suits Jay wore on his album covers to Big taking his nickname from King of New York—can be traced directly to the Queens native. But G Rap is more than just a blueprint. The Juice Crew linchpin was also one of the great technical innovators of his era, his cadences so pliable they would sound fresh if heard for the first time today. With 1992’s Live and Let Die, his third album with DJ Polo, G Rap cemented himself as one of the great American crime writers in any medium.

Q-Tip (1993)

As the 1980s gave way to the ’90s, the Native Tongues movement spearheaded by A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, and the Jungle Brothers was fast becoming one of the most significant aesthetic and ideological forces in rap. Tribe’s second album, The Low End Theory, was particularly foundational, stripping away layer after layer from each song’s mix until little remained beyond bass and the Queens native Q-Tip’s slightly biting wit. Their follow-up, Midnight Marauders, was released toward the end of 1993, by which point the Native Tongues were losing collective steam (that was the year a De La song famously stated “That Native shit is dead”). But Marauders confirmed Tribe as stars big enough as to be undeterred by that sand-shifting, and Q-Tip as the buoyant, increasingly provocative engine behind them, an MC and producer with few peers, the purest representation of rap’s connection, in sound and spirit, to jazz.

Nas (1994)

Illmatic was not a surprise. Nasir Jones was a prodigy—raised in the Queensbridge Houses and bitter, even as a 13-year-old, that the Juice Crew didn’t recruit him for the Bridge Wars. His verse on Main Source’s “Live at the Barbecue,” released when he was still 17, made him a commodity; the following year, in 1992, he signed to Columbia, dropped the “Nasty” from his stage name, and got to work on that debut album, which would be rushed to avoid bootlegging and immediately dubbed a classic by The Source. And still, the fervor barely captures the achievement. Over a collection of beats by the most in-demand producers in New York—Q-Tip and Pete Rock, DJ Premier and Large Professor—Nas deepened the grooves that Rakim had first scratched, his labyrinthine verses full of hairpin turns and internal rhymes so complex as to be mathematical. The technique dazzled, but was ultimately beside the point. What elevates Illmatic above even those rare albums that match its precision is the depth of feeling Nas brings to his early childhood memories of Queens, the hints of performance in his nominally reassuring letters to a friend behind bars, the kind of premature weariness only a precocious 20-year-old can channel on his birthday. Just months before, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) had offered a tantalizing new paradigm for how rap songs could sound. Illmatic did something different: It looped back around to rap’s beginnings—Nas’s transparent baby face on its cover, clips from Wild Style in its intro—and recoded the DNA that mapped the genre’s most basic elements.

The Notorious B.I.G. (1995-97)

There is no evidence of Christopher Wallace being less than a genius. The few early, amateur recordings that survive betray superhuman timing and a fearsome intelligence; Big was the most observant person in the room and also the funniest, his words tumbling out in perfect time. When the studio sessions for his first album were halted because the guy who signed him got fired from the label, Big shrugged, then moved down to Raleigh so he could sell drugs and keep eating. When he came back to New York the following year, not only had his skills not atrophied—his voice had grown richer and smoother, his natural charisma translating even more clearly than before. Oh, and he didn’t need to write the rhymes on paper anymore. He simply remembered them.

At this point even the most arcane bits of trivia are widely known. (There are a lot of murals.) But the cottage industry actually undersells Big’s sheer brilliance—the breathtaking detail of his story raps, his disarming willingness to say truly ugly things on record, the way that ugliness burnished his myth while undercutting the very notion of rappers as heroes. Ready to Die is like a brilliant short story collection, each song finding a novel way into its narrative action, each character distinct. Not even Rae and Ghost’s disapproval could make a meaningful dent. Its follow-up, the double-disc Life After Death, is a two-hour heat check, proof that Big had mastered every style of popular rap before the age of 25.

In his too-brief life, Big was not only the best and most popular rapper in New York, but the one who made that crown seem crucial. See “Kick in the Door,” the swaggering DJ Premier production from Life After Death’s first disc, a cryptic diss so beloved that Nas would later boast he was one of its targets. On that song, Big mocks the rappers who “took home Ready to Die, listened, studied shit” and those who were “still recouping,” perhaps a reference to Nas, who was rumored to have rented clothes for the 1995 Source Awards. Whatever his intentions, “Kick in the Door” made one thing clear: The mantle was Big’s, and anyone seeking it had better up his game dramatically.

Vacancy (1997)

On March 9, 1997, Christopher Wallace was shot and killed at the corner of Fairfax Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. He was 24 years old. The case remains unsolved.

The absence left by the tragedy is not the same as the creative ebbs and flows documented throughout this exercise; Big left a void that would not immediately be filled. This is not to say there were not significant records coming out of New York. Mase’s Harlem World and Puff’s No Way Out kept Bad Boy briefly in the limelight; Busta Rhymes was becoming a genuine solo star after splitting from Leaders of the New School; on a smaller scale, the release of Company Flow’s Funcrusher Plus presaged the Def Jux takeover that would happen in the first half of the next decade. But the summer belonged to Wu-Tang. From November of ’93 on, the group from Staten Island had rap in something just short of a chokehold: Not only was 36 Chambers a landmark achievement, but at least three of the five solo albums released in that span could be considered masterpieces. Their second group effort, Wu-Tang Forever, was maximalist in every sense, a sprawling double disc that features some of the members’ sharpest, most idiosyncratic writing—and likely confirms Ghostface Killah as the best rapper in New York at a moment when there couldn’t be one, at least in spirit.

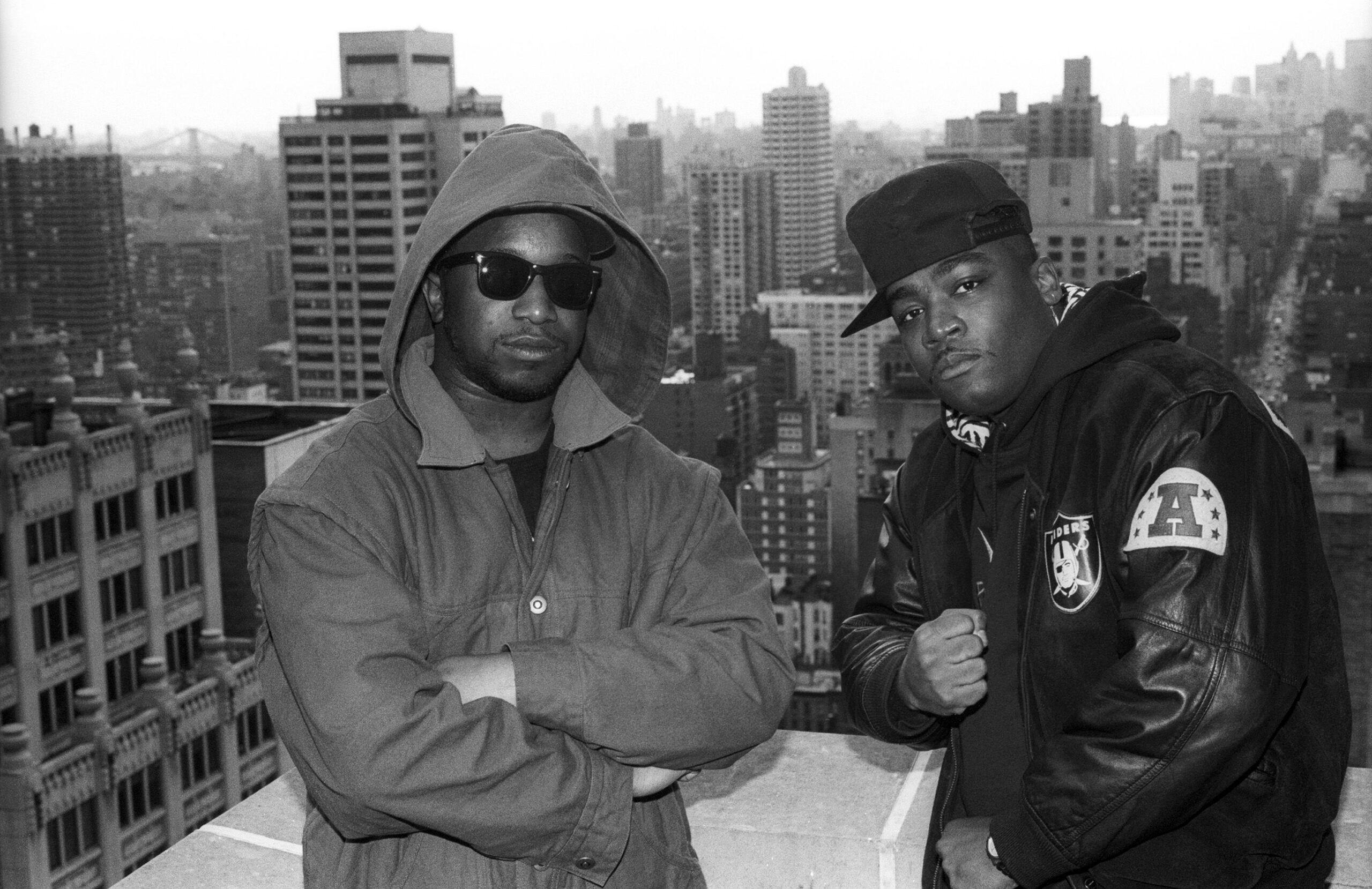

DMX (1998)

It is strange to consider that there was time before DMX. His 1998, which saw the release of a debut album, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot, and its follow-up—Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, coaxed out of him by Def Jam, which offered a million-dollar bonus if he could cut another album in 30 days—was practically apocalyptic. Raised way up in Yonkers, Earl Simmons honed his jagged voice and accumulated three lifetimes’ worth of stories and spiritual angst before unleashing them in what came to seem like a single, unbroken outburst. Few artists in any genre have had such an unquestionable stranglehold over their fields at a given time. What makes X’s music resonant to this day is his ability to lurch from an urgent, all-id present tense to moments of tortured self-inventory. He would plead with God and snarl at his enemies; sometimes he caught himself mistaking the two.

Jay-Z (1999-01)

After Big’s death, Jay-Z made an explicit move for the throne. In My Lifetime, Vol. 1, released less than eight months after the assassination, taps Puff and the Hitmen for production duties and features a number of crossover attempts, including one called “The City Is Mine.” It sold significantly better than 1996’s Reasonable Doubt, but did not quite make him a superstar; he would cross that threshold in ’98, with Vol. 2... Hard Knock Life and its quartet of massive singles. But ’98 belonged to DMX. It wasn’t until the following year, when Jay stabbed Un Rivera dropped his third album, Vol. 3… Life and Times of S. Carter, that he could credibly claim New York as his own.

Born in Brooklyn and raised in the Marcy Houses, Jay apprenticed under Jaz-O, who was known as one of that borough’s best unsigned rappers until he landed with EMI and allowed that label to torch his image—with a video that featured his young apprentice. Jay took what he learned from Jaz (the cautionary business tales, the hypertechnical fast-rapping that he would perfect, then slow down into something more wieldy) and reassessed. By the time Vol. 3 was released to huge fanfare—it went triple-platinum in 14 months despite rampant bootlegging—Jay was simultaneously the center of the pop-rap universe and one of the genre’s most daring stylists. This sort of dual-track focus allowed him to hold the crown while he transformed his image: Vol. 3 gave way to 2000’s The Dynasty: Roc La Familia and then to The Blueprint, on which Jay sank deep into midtempo raps over warmly rendered soul samples and successfully cemented his legacy among establishment critics.

From its inception, rap had evolved at a breakneck place; those at its center one day might seem obsolete the next. But Jay-Z released albums as if by metronome, one every year, and grew steadily bigger. He was ruthless in boardrooms and had an omnivorous ear that let him subsume bubbling styles into his own. Jay famously wore a Che Guevara shirt when he taped MTV’s Unplugged on November 18, 2001, but at that moment he seemed more like Castro: inevitable and here indefinitely.

Nas (2001-02)

While Jay was making his way to the top of the food chain, Nas was watching his reputation erode. His excellent second album, It Was Written, was the subject of considerable debate among fans and critics when it came out, some balking at its occasional commercial sheen. A planned third album was decimated by leaks, and each of two LPs he released in 1999 was met with mixed reviews. On The Blueprint, Jay attempted to put Nas out of his supposed misery with “Takeover,” a diss song that poked at Nas’s diminishing credibility and implied a relationship with the mother of Nas’s child. It did not seem to leave a lot of room for spin.

But five days after Jay taped Unplugged, his reign came to an abrupt end. “Ether,” Nas’s scorched-earth response to “Takeover,” was so powerful that it tipped the balance of power back in his favor almost instantly, paving the way for his triumphant, five-mic comeback album, Stillmatic. There is a reasonable case to be made that, in hindsight, “Takeover” is both a better song and more surgical diss than “Ether.” But to hand the fight to Jay is to ignore every shred of context. If the King of New York title is like a boxing belt, and each individual feud its own match, then that sport’s rules apply: It doesn’t matter who’s ahead on the cards when someone lands a knockout blow.

50 Cent (2003-04)

All the way back when 50 Cent was “Fifty Cent,” Jam Master Jay was running the Queens native through a very specific type of boot camp. The Run-DMC legend, who signed the rapper to a production deal after a chance meeting outside a Manhattan club, would invite 50 to the studio, put on a beat, and make him write a hook—then another, and another after that. It’s the type of rote work that would likely frustrate a young artist; it’s also the type of experience that would come in handy if that young artist was one day left for dead and expected to claw his way back if he expected anything at all.

The story of 50’s ill-fated Columbia deal, near-assassination, and long recovery is, by this point, well known. Even someone unfamiliar with the details would recognize the aftermath: the bulletproof vests as couture, the lisp caused by shrapnel left in his tongue. When the industry was convinced 50 was too toxic to touch, he forced the issue, recording a deluge of bewilderingly charismatic mixtape songs, the funniest and most menacing in rap at that moment. What followed—the deal with Interscope, the XXL cover with Eminem and Dr. Dre, the debut album that was as hyped as any since Doggystyle—was a well-deserved coronation.

By the time Get Rich or Die Tryin’ was out, 50 was teasing the G-Unit album, Beg for Mercy; when that dropped, he was already giving interviews about his sophomore set, originally called St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. It would later be revealed that during this period he was also writing songs for the Game, whose own debut, The Documentary, was a priority for Interscope. By the end of that run, 50 had simply burned out. But at that point, he was so massive that his faltering—he lost a first-week sales showdown in the fall of 2007 to Kanye West—was cast as a signal that all of gangsta rap was obsolete. There has not been a superstar like 50 since 50, and the economics of the record industry are such that there likely never will be again. Drake, whose breakthrough at the end of the 2000s marked the beginning of a new era, is bigger by any measure, but his continued supremacy is the product of careful calibration: His syntax is constantly updated to flow with the prevailing winds, as is his Rolodex. In 2002, 50 made himself inevitable through brute force, a villain to his core.

Cam’ron (2005)

You could argue that Cam’ron’s creative or cultural apex came earlier—in that post-9/11 fugue when Dipset was gleefully referring to itself as “Harlem’s Al-Qaeda”; on 2002’s Come Home With Me, which featured his first major hits; on 2000’s SDE, simply because he said “I ain’t no rapper, B, I skeet Uzis / And I can’t act—turned down three movies”; or all the way back in high school, when he was allegedly outplaying Stephon Marbury in high school ball. But you seize the opportunity when it’s presented. With Jay-Z’s retirement and 50’s burnout rapidly becoming apparent, Cam struck at the very end of 2004 with Purple Haze, a delirious, overly long album that contains some of his most gleefully eccentric writing, some of his most poignant work, and songs that would go on to spawn entire subgenres of rap years later (map “Get ‘Em Girls” onto the maximalist circa-2010 Lex Luger beats that would define the decade to come). Few rappers from New York—or anywhere—have had the gift for language that Cam does, or the will and wit to bend it into such Daliesque shapes. One of the two great disses of 50 didn’t hurt, either.

Ghostface Killah (2006)

By 2006, Ghostface had already released two of the greatest rap records ever by a solo artist, arguably stolen a third, taken his group’s sprawling second album on all scorecards, and rattled off so many other staggering verses that some could disappear into the file-sharing abyss without causing him to pause or falter. And still, Fishscale seemed like a rebirth, a mid-career Supporting Actor Oscar that keeps the offers rolling in. At a time when rappers and fans were wringing their hands over hip-hop’s future (and New York’s place in it), Ghost returned to his careening, Joycean crime stories, burglars’ stomachs growling as they smell onions grilling below their break-ins. Speaking of Oscars, his second LP of the year, More Fish, features one of the most charmingly outlandish tales in Ghost’s repertoire, a song about how his original script for a Ray Charles biopic—and idea to cast Jamie Foxx in the starring role—were stolen during a meeting at a P.F. Chang’s.

Max B (2007-08)

A half-decade after 50 Cent made a mockery of the A&R process by littering mixtapes with pop hooks catchier than the current Top 40, and just as Lil Wayne was turning the beats for radio hits into canvases for virtuosic freestyles, the Harlem-bred Max B blurred every meaningful line that remained: the ones between harmony and monotone, the avant garde and the middle, man and myth. Despite spending only five years of his adult life free from prison or jail, Biggaveli has an extensive catalog, the best of which was released between January 2007, when he was bailed out of jail, and June 2009, when he was found guilty on murder conspiracy and robbery charges and sentenced to 75 years in prison. (That sentence was shortened by a 2016 plea deal. Many reports suggest a 2021 release date, though at press time Max B remains incarcerated.) His work is comical but full of dread, muddy but with a distinct musicality, and his tapes from this era are DatPiff classics that could just as easily have been best sellers.

Vacancy (2009)

By the end of the 2000s, New York rap seemed to be in disarray. The traditional CD sales model had crumbled, throwing the label system into chaos; years of fretting about ringtones, snap music, crunk, and the South generally had reached deafening levels. But 2009 did see three major albums by three New York veterans, each remarkable in its own way: MF DOOM’s final studio album, the gruff, muscular Born Like This; Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… Pt. II, which smartly splits the difference between nostalgia and the cutting edge; and The Ecstatic, which is secretly Mos Def’s best solo LP. Those last two albums reach back even further, making superb use of Slick Rick—on OB4CL2’s cheeky “We Will Rob You” and The Ecstatic’s “Auditorium,” which is built around one of the finest verses of The Ruler’s career.

Roc Marciano (2010)

Roc Marciano is like if the Velvet Underground only wore mink: Seemingly everyone who heard the self-produced solo work he started issuing in 2010 launched his or her own underground rap projet, and his influence—the minimal, sometimes drumless beats, the cartoon luxury enjambed against horrific naturalism—is widespread in mainstream and underground rap today. Starting with his seminal Marcberg, the Long Island native stripped any sound or narrative structure he found excessive from his songs, while reveling, among what remained, in excess itself. He raps like a Bond villain whose origin story is simply “Koch-era New York City.”

A$AP Rocky (2011-12)

While a new underground was taking shape, the early 2010s were a more uneven time for the pop-rap side of New York. There were entrancing one-offs—“212” is almost enough to single-handedly win the crown for Azealia Banks—but few obvious heirs until Halloween 2011, when A$AP Rocky uploaded his breakthrough mixtape, Live.Love.A$AP. The Harlem native’s $3 million deal with RCA had made him the subject of considerable speculation, but it was the tape itself that signaled the arrival of a major player. Masterminded by A$AP Yams, the enterprising Dipset-intern-turned-Tumblr genius, Rocky’s style was a web of interconnected influences: Memphis and Houston, high fashion and street sensibility, flourishes from late-2000s indie music and his birth name, Rakim. Rocky has gone on to be a reliable chart-topper and fixture on the festival circuit; it was at his career’s very beginning when he held his hometown in a vise grip.

French Montana (2013)

Karim Kharbouch grew up outside of Casablanca. He became French Montana only after his family moved to the Bronx, where he immersed himself in New York rap culture by producing with a friend a series of DVDs called Cocaine City, Smack knockoffs that became very popular among the sort of people who buy Smack knockoffs. An early alliance with Max B made him a semi-compelling also-ran; circumstance and just enough charm made him, for a brief moment in the early 2010s, the most inescapable New York rapper. The title of his album from 2021, They Got Amnesia, is appropriate: Anyone who denies his ubiquity circa 2013 is only lying to themselves.

Bobby Shmurda (2014)

It’s been well documented that Bobby Shmurda’s story is a microcosm for the way rap music is used by police and federal agencies as a pretext for harassing or jailing Black people. But the Brooklyn rapper’s breakthrough single, “Hot N****,” is also emblematic of what makes New York hip-hop so regenerative and exciting: Here is a completely unknown teenager who, in three minutes and without the aid of a chorus, not only made himself a star, but made it seem for a second like the city, the world orbited around him and his friends. “Hot N****” takes its beat from a Lloyd Banks song released two years prior. That Banks song was inconsequential, which is not to say it was thrown together thoughtlessly. “The sound of the crow [in the beat] was because I loved those gothic horror movies,” its producer, Jahlil Beats, said recently, “but it was also to symbolize that death is always stalking Black people in America. It can strike at any moment.”

Nicki Minaj (2015)

It is very easy to imagine a course of history in which Nicki Minaj is associated with cities other than her hometown. The Trinidadian rapper, who grew up in Queens, was introduced to many on Lil Wayne’s 2007 mixtape Da Drought 3; her own breakthrough record, 2009’s Beam Me Up Scotty, was recorded mostly in Atlanta, where she became closely associated with Gucci Mane, the greatest talent scout of his generation. But a half-decade after Scotty, Nicki had stepped out of all those shadows. She was cutthroat but wildly animated, with pop hits and menacing mixtape cuts dropping simultaneously. Her album from 2014, The Pinkprint, was a blockbuster, merging her Billboard instincts with her most outre, experimental tics.

Ka (2016)

After trying and failing to break into the industry in the ’90s as a member of the group Natural Elements, Ka retreated for years, returning in the 2010s as one of hip-hop’s great auteurs. His formally inventive, chillingly cryptic records, which are not only self-produced but packaged and shipped by hand, made waves to the point that he was the target of a 2016 front-page hit piece in the New York Post. In the ecosystem of underground rappers who have scavenged for old styles to repurpose in radical new ways, Ka is the apex predator. Honor Killed the Samurai, his album from the same year as the Post piece, is a master class in economy, not an inessential hi-hat or preposition to be found. While he seldom writes long, linear narratives, he is not dealing in the quick quips of early 50 Cent or in Ghostface’s psychedelic free association. Ka writes instead in short thoughts that often turn to aphorism, as if every bar is something a wise uncle often repeated. But there is little comfort to be gleaned from the advice. Dread suffuses his work, as if he’s frozen in the last few seconds before a horror movie’s first kill.

Cardi B (2017-18)

It is tempting to see transfers of power as paradigm shifts in terms of how music will be discovered and distributed in the future—to say that 50’s mixtape run marked a new era of artist agency, or that Max B’s signaled the end of albums as a format all together. Cardi B’s rise dispels that notion. Despite entering the public consciousness through Instagram and reality TV appearances, Cardi’s music—her breakthrough mixtapes and debut album, 2018’s Invasion of Privacy—quickly allowed her to take over terrestrial radio, making her a monocultural figure in a time that was thought to be incapable of producing any more.

Pop Smoke (2019)

Though drill, with its roots in dance music’s complex drum programming, was a uniquely Chicagoan invention, its Brooklyn permutation runs neck and neck with Ka and Roc Marci’s sneering minimalism as the most compelling subgenre in 2010s New York—and its breakout figure, Pop Smoke, quickly became the city’s most obvious new star in some time. From his debut single, “Welcome to the Party,” the Canarsie native’s voice was unmistakable, a mix of 50 Cent’s husky baritone and Max B’s playful atonality. His first mixtape, 2019’s Meet the Woo, was produced almost entirely by 808Melo, an East Londoner whom Pop Smoke found online and flew out to New York. The unlikely pairing yielded an instant classic. Pop Smoke became so beloved in the city that by the summer of last year, the seemingly apolitical “Dior” came to soundtrack protests against police violence.

But he did not live to witness this repurposing of his single. On February 19, 2020, Pop Smoke was murdered during a home invasion in Los Angeles. He was only 20 years old.

Vacancy (2020-Present)

As was the case after Big’s murder, Pop Smoke’s death leaves a vacuum. Brooklyn drill is still mutating—it’s now spread to the Bronx—and the post–Earl Sweatshirt sound typified by rappers like MIKE and Navy Blue is thriving. But the latter scene seems uninterested in the type of celebrity we’re noting here; none of Pop’s drill contemporaries, like Sleepy Hallow or Sheff G, have quite been able to seize the mantle, and while Fivio Foreign was this summer’s buzziest rapper based on his Donda appearance, he’s a ways off from being fitted for the crown. Wiki, once an irreverent upstart as the frontman of Ratking, is now a reliable veteran who excels in the sort of autobiographical writing that is quickly canonized. Ka and Roc Marciano are still refining their visions in careful increments; the Griselda crew is having a moment, though they hail from Buffalo and seem to be making a knowing play for nostalgia. For the moment: a void.

The king or queen of New York as a concept will never be as tantalizing as it was during Big’s reign, and could never be enjoyed with the same unqualified fun after his death. It also seemed to hold less prestige as the 2000s wore on and New York was deemphasized in national rap conversations. But at the beginning of the 2020s, hip-hop is in a fascinating place: While the internet allows for rapid exchange of ideas and aesthetics, the genre is in some ways as regionally siloed as ever, with distinct stylistic movements in Michigan, Baton Rouge, Los Angeles, and exurban Florida to name just a few. Pop Smoke’s run was a reminder that New York is as likely as any city to produce the genre’s next great driver or interpreter of sound—and that, when a new star does come from New York, he or she can bend the entire genre into their orbit.